The first man gets the oyster, the second man gets the shell.

— Andrew Carnegie

It’s been a mild winter but, hey, it’s winter. And things have been comparatively stressful here at History Central, considering the various degradations involved in the (not particularly) good ol’ college days of horsing and flagrant Jim Crow that we’ve been ruminating upon of late. It’s high time we take a breather and move back into the sunshine for a bit, seeking some much-needed balance by reminding ourselves of the better side of our natures.

So I naturally thought of Ted Cruz ’92.

I’d hasten to add this doesn’t necessarily involve a similar worldview, but instead our mutual approach to shedding the inevitable pressures of our everyday lives: singing Broadway show tunes. True, he gets to sing them to his wife on the phone – my wife’s lawyers have made sure that I won’t do the same, so I tried my friend who’s a partner at Goldman Sachs, and he won’t take my calls now either – but the inspiration and beauty of melodic poetry are uplifting anytime. The Cruzes are, so far, silent on the range and depth of the senator’s repertoire, but my guess is that it differs somewhat from my own, not so much because I suspect Disney show tunes on his part (actually, I’m a sucker for “Hakuna Matata”), but I tend more toward a rather odd selection of, oh, maybe “Pore Jud Is Daid,” or “Try a Little Priest, ” or “The Song That Goes Like This.” Nothing tops the Great White Way.

So I naturally thought of Aaron Burr Jr. 1772.

In one of the most predictable events in decades, I’ve become transfixed, apparently along with a good portion of the Western Hemisphere, by the Broadway production of Hamilton. Describing Lin-Manuel Miranda’s creation as a tour de force is pitifully inadequate; it’s the content equivalent of three or four stage dramas run in two hours and 45 minutes, but somehow with the entertainment value of any of those gaudy musicals. I keep playing the rap songs over (no, I haven’t actually seen it yet – I was hoping my friend the Goldman Sachs partner could get me in, but as you recall, he won’t answer …) and marveling at the blend of historical detail and catchy stagecraft. And of course, the second banana in the piece is our old fellow alum Aaron Burr, the first Princetonian to be elected to national office (vice president in 1800) and, despite or because of repeated personal revivals, still one of the great mysteries of American history. Among accomplished men of his era, he probably comes off better than Benedict Arnold, but beyond that it gets really dicey. In Hamilton he serves many functions at different times, often in counterpoint to the protagonist: As early as 1776, Hamilton is jealous of Burr’s two-year honors career at Princeton and wants to replicate it (John Witherspoon would quash that ambition, and Columbia gained a prized alum); at the end, Hamilton’s support of Jefferson over Burr for president is the major cause of their duel in 1804. And ironically, they both end adrift on the seas of history, Burr as Hamilton’s killer and Hamilton as a wraith in Washington’s shadow, belittled post mortem by his own Federalist party. Washington’s wisdom for these two historic second-place finishers comes in the finale:

Let me tell you what I wish I’d known

When I was young and dreamed of glory

You have no control: Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?

This selective (if you like an orderly universe) or arbitrary (if you’re an entropy disciple) nature of history extends all the way up to the most crucial issues: In Hamilton, Miranda portrays Hamilton at the duel as firing in the air, allowing a confused Burr an unchallenged shot. In Gore Vidal’s wonderful Burr, which began his great Narratives of Empire historical novels in 1973, the narrator (years later) is satisfied that Hamilton indeed shot first but aimed and missed, and so Burr was justified. To this day, historians mud wrestle over the “truth” of the case, as if the fame of Washington, Jefferson, Adams, and Madison had not long since eclipsed both duelists. In the great Hamilton/Burr debate, the fickle finger of fate has seemingly arisen to point directly at … no one.

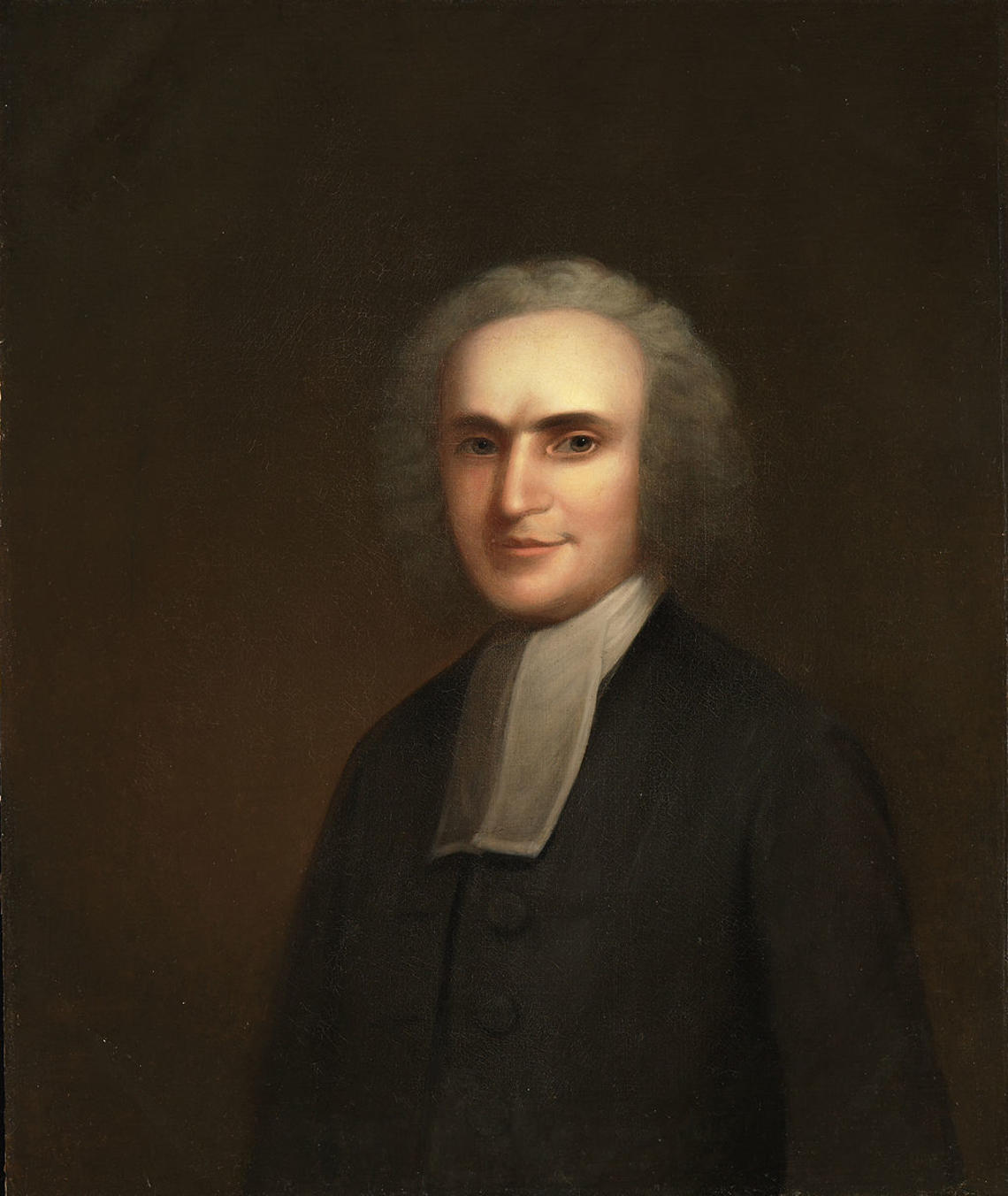

So I naturally thought of Aaron Burr. No, not him; Burr Senior, the other one.

Princeton’s formative years were so intertwined with the Great Awakening and the American Revolution that recalling other crucial influences is often next to impossible (he said, contemplating thesmoking ruins of Nassau Hall in 1777). What we often do is resort to symbolism, and the overarching symbol of the age is Witherspoon. A twofer if there ever was one, he came over from Scotland as if from heaven in 1768 to reinforce the struggling Enlightenment loyalists who had created the college 22 years before, and who recently had seen three presidents go from inauguration to the grave (more of that later) in only eight years. He then proceeded to become a bulwark of the Revolution and the re-creator of the ruined school afterward.

But the college was there – in both senses, in Princeton and in existence at all – in large part because of Aaron Burr Sr. Princeton’s second president was actually its leader before the fact. The top graduate of his Yale class of 1735, he alone was sent to New Haven by the seven New Lights from New Jersey in 1742 (an arduous four-ferry trip) to plead on behalf of outspoken young student and ardent New Light David Brainerd. Brainerd’s subsequent expulsion caused the Jerseyans – four clergymen and three laymen – to move ahead at Burr’s urging with their college, which opened in Elizabeth in 1746 under Rev. Jonathan Dickinson, who promptly died. Burr, only 31, essentially the only option left, voluntarily moved the whole caboodle up the road to his parish in Newark, and began to laboriously build the college as president with the aid of his trustee friends and the new governor, Jonathan Belcher.

He and Belcher paved the way organizationally at the school while Samuel Davies and Gilbert Tennant raised funds in the British Isles; their choice of Princeton for the new college building and site was made official in 1753, while the faculty and student body grew under Burr each year. By the time the college moved to Nassau Hall (the plaster still wet) in November 1756, he was fatigued and dangerously delicate, but his position as both primary tutor and front man for the institution required his presence in Massachusetts, in Elizabeth, and in Philadelphia. On returning sick from the south in early 1757, he found that his friend Belcher had died, and he immediately left for Elizabeth again to preach the eulogy. The decision proved fatal.

Burr’s death from exhaustion at age 41 opened the floodgates. His father-in-law, the great preacher Jonathan Edwards, was inveigled into succeeding Burr in Princeton; Edwards was inoculated with live smallpox and died within months. Burr was the first interred in the now-renowned Presidents’ Plot in the Princeton Cemetery and Edwards the second. Edwards’ 27-year-old daughter Esther, wife of Aaron Sr. and mother of their 2-year-old son Aaron Jr., followed of smallpox in 1758, her mother the same year. Whatever part that all had in forming the famously irritable Aaron Jr., it certainly didn’t help. He ran away from his adoptive home with his uncle multiple times, once trying to get to sea. The trustees originally had intended to name the main college building Belcher Hall in honor of the governor; he demurred, but did he suggest Burr Hall in honor of his friend the skillful president? No, “ Nassau Hall,” in honor of somebody who never set foot in the Western Hemisphere or heard of a New Light. To be sure, at long last there is today an Aaron Burr Hall at Princeton (the Old, Old Chemistry Lab, now home to the anthropology department), out of the way across the street from Firestone. Across Washington Road, actually. In front of Burr Hall is a historical marker honoring George Washington, who rode by once or twice. Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?

In Hamilton, there is a lovely duet between Hamilton and Burr Jr. set in 1783 when they were still on speaking terms. A promise to their infant children Theodosia Burr and Philip Hamilton, it yearns for a brave new land to rise from the tumult of war:

If we lay a strong enough foundation

We’ll pass it on to you, we’ll give the world to you

And you’ll blow us all away ...

But both children predeceased their fathers (the younger Hamilton, unbelievably, in a duel). At the end, Aaron Burr Jr. 1772, loyal alumnus and benefactor of the college, was glimpsed in 1835, the lonely survivor at 79, in contemplation at the Presidents’ Plot, at the graves of his father and grandfather: laid to rest more than 75 years before, both martyrs of the school, both eclipsed by Witherspoon. Barely a year later, the one-term vice president joined them there.

Sometimes, I find myself humming a chorus of “ Empty Chairs at Empty Tables” from Les Mis.

Gregg Lange ’70 is a member of the Princetoniana Committee and the Alumni Council Committee on Reunions, an Alumni Schools Committee volunteer, and a trustee of WPRB radio. He was a recipient of the Alumni Council’s Award for Service to Princeton at Reunions 2010.

No responses yet