Recession clouds faculty retirement planning

Until the economic downturn, colleges and universities across the nation were anticipating a wave of retirements over the course of the next decade. But now, it seems some faculty members are reconsidering their plans because of financial uncertainty.

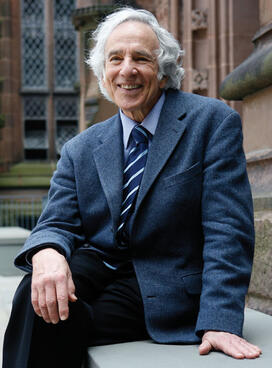

Consider Michael Wood, Princeton’s Charles Barnwell Straut Class of 1923 Professor of English and Comparative Literature. He originally planned to sign a phased retirement agreement last fall that would keep him employed on a half-time basis for the next four years.

That was before, as he put it, the “you-know-what hit the fan.”

“I liked the idea [of phased retirement] because it allowed me to make way for younger colleagues, get more writing done, and still stay in touch and do some teaching,” he said in an e-mail message from Mexico. “For obvious financial reasons — chiefly the dip in everyone’s pension funds — this excellent idea suddenly seemed less excellent, and I decided to think again.”

Wood now intends to retire after two years of full-time employment (he is on leave this semester), provided the overall financial effect is the same as his original plan. “If [the sums] don’t work out,” he added, “I’ll ... keep thinking.”

Wood is not alone in his rethinking, but the full effects of the financial collapse on retirements may not become clear for several years. Twelve faculty members are transferring to emeritus status in the next three months (see list, page 14) — a number in line with previous years.

Stanley Corngold, professor of German and comparative literature, is among the faculty members who will retire this year. “I decided to retire three years ago,” Corngold explained. “And last year it occurred to me that this might not be the optimal time to retire,” he continued, pausing to laugh, “but I never seriously reconsidered my decision.”

Corngold said he had only about 25 percent of his investments in volatile items, which helped to minimize the extent of his losses. Nonetheless, he said, “It’s certainly not very pleasant, and [my wife and I] are a little cautious about spending money now.”

Like many professors who transfer to emeritus status, Corngold hopes to maintain an office and active presence at Princeton. “I can think of five books I’ve got to write and edit,” he said.

Of the five full professors in the German department, Corngold and two others are retiring. Department chairman Michael Jennings said the department has known about these retirement plans for quite some time and was able to plan accordingly. This included hiring three “superstar German scholars” three years ago, each of whom teaches for one out of every three semesters. Two new assistant professors will join the department in the fall. One professorship will remain open, partly because of the financial downturn.

Dean of the Faculty David Dobkin said the University will have “a significant number of retirements this year and next. The situation for future years is less clear. I have had some retirement discussions, perhaps half as many as in a previous year, and expect some of them to bear fruit. But there is a lot of uncertainty.”

In 1994, federal legislation declared the mandatory retirement age of 70 for tenured faculty members to be illegal. Since that time the average age of faculty transferring to emeritus status at Princeton has crept up, Dobkin said — now, it’s about 75.

What will it mean for Princeton, and academe in general, if the recession pushes those numbers even higher?

“I worry about departments getting into a stagnant place,” Dobkin said, explaining the need for a balance between fresh Ph.D.s and senior faculty members. “I am an advocate of bringing in new people, getting a department to grow and change over time. At the same time, traditions in departments are very valuable. Finding that balance is often a challenge.”

Valerie Martin Conley, the director of the Center for Higher Education at Ohio University and author of a 2007 American Association of University Professors report on college retirement policies, said she hopes institutions will pay increased attention to faculty development for mid- and late-career faculty members.

At Princeton, the future is likely to bring faculty-retirement incentives to encourage healthy turnover, though the time frame for any new initiatives is unclear. Currently, retirement-eligible faculty (those who are at least 55 years old with at least 10 years of service at the University) may receive continued health-care benefits, and emeriti faculty members are eligible for reappointment to research and teaching positions.

No responses yet