At 22, Kate Poole ’09 was a radical. She had lived on a commune in Thailand, joined protesters on the first day of the Occupy Wall Street encampment, and was a member of a nonprofit in West Philadelphia that focused on social justice. And she had just learned that she had two trust funds worth more than $2 million.

“I felt shocked, surprised, isolated,” Poole says. “I was not sure what that meant for my participation in social-justice movements.” What she really wanted to know was: “Was there money in my name causing harm?”

Her mother had hesitated to reveal how much was in the trusts and how it was invested, fearing, says Poole, that her daughter would do something rash, like give it all away. Eventually she showed Poole how the money was invested. There was stock in Exxon and a mining company, which deeply troubled Poole. And she had an even more significant question: How did her family acquire its wealth?

Poole grew up with her mother and brother in her great-grandparents’ sprawling house in the Baltimore suburbs. The family had owned a straw-hat factory in downtown Baltimore in the early 20th century. Poole began studying the city’s history, learning about the redlining that prevented African American families from getting bank loans and the racially restrictive covenants that prohibited them from purchasing land. She came to the conclusion that her inheritance came at the expense of others.

“My family was able to accumulate wealth because of a racist system that has supported white families while locking out African American communities,” Poole says. She was clear about what she needed to do: “I have an obligation to work toward repair and wealth redistribution.” She joined a burgeoning movement of young people who have inherited money and are asking tough questions about how their families achieved their wealth. Then they work to rectify what they perceive as their ancestors’ wrongs by using their money to help repair the damage.

Poole is one of more than 650 people — a handful of whom are Princeton alumni — who are members of Resource Generation, which describes itself as “a multiracial membership community of young people with wealth and/or class privilege committed to the equitable distribution of wealth, land, and power.” Part support group, part financial adviser, Resource Generation is a meeting place for like-minded “inheritors,” as some call themselves. The group helped Poole “come into integrity and reckon with my wealth accumulation,” she says.

Christopher Ellinger ’78 helped to start Resource Generation — which is geared to people ages 18 to 35 — in 1996. He and his wife had donated half of his inheritance by their early 30s and founded Bolder Giving, a group that encouraged people to donate more of their money. “In the old model, people started philanthropy when they retired. Why wait?” asks Ellinger (known as Christopher Mogil at Princeton). “If you care deeply about the world, you likely can make a much greater difference if you act now.” His values have stuck: He’s now 63 and has no regrets about giving so much away.

Wealth and racism are inextricably linked, according to Resource Generation. Its members see an economic system that has exploited people of color as well as the poor and members of the working class. Repairing those past wrongs can only be achieved by the redistribution of wealth. Critical to that work is supporting — not leading — organizations that are led by working-class and poor communities and people of color who are fighting for economic and racial justice.

Some participants say their wealth makes them feel guilty, and coming clean about one’s money is critical. “If I’m going to activist meetings and hiding my class background, there’s a dishonesty in that,” Poole says. “There’s power in showing up as your full self.”

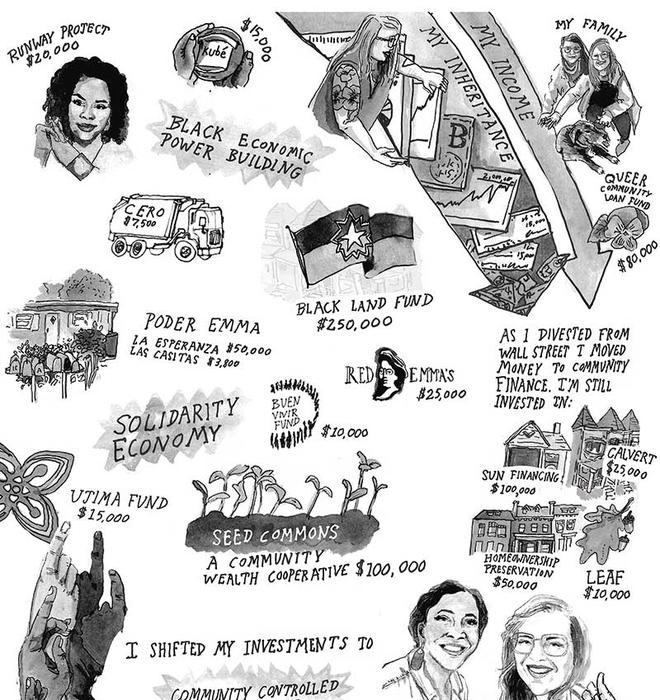

Resource Generation’s stated goal for its members is simple: Give all or almost all of your wealth away. Poole joined in 2013 and started giving away “tens of thousands, then hundreds of thousands” of dollars, she says. So far, she has given away more than $440,000, by her account. And $1.1 million is in investments that support racial and economic justice.

While at Princeton, Megan Prier ’11 learned she had a trust fund. After her tuition was paid, she was left with an inheritance of between $150,000 and $200,000. Over the last several years, she has given all the money away.

She began the process — as do many of those who join Resource Generation — by formulating her “money story.” Growing up outside Philadelphia with parents who worked as veterinarians, Prier was told her family had worked hard and saved to pay her college tuition. She learned over the years that “my family has gained and built wealth over generations originating with colonization in the 1600s. I have records of my ancestors stealing land from Indigenous peoples on the East Coast during the early days of colonization.” Other ancestors, however, fought against oppression. Some helped enslaved people escape through the Underground Railroad, and Prier’s grandfather, as president of the Bank of Philadelphia, had a role in ending redlining, she says.

Prier made a donation to the Lenape tribe. The rest of her inheritance went to two dozen grassroots organizations in Oakland, Calif., where she lives, and others around the country. “They work against racism and wealth inequality and get people’s basic needs met in disenfranchised poor communities,” she says.

Prier’s perspective — shared by Poole and others in Resource Generation — is that “poor people living in poverty have the solutions, and are the experts in poverty,” and they are the ones who should lead the implementation of solutions and direct how resources are used. “I try to redistribute it in ways where I have limited control over it,” says Prier, who is 30.

After college, Prier studied in Europe and worked in different parts of Africa on agriculture and public infrastructure. “I had thought that with my engineering degree, I would go out and solve world problems, but I realized it was detrimental for me to be there,” she says. “My very presence was implying I was there to tell them how to live their lives.” She now does design work that aims to build public infrastructure, such as bathrooms, that meets basic needs, and to improve air quality. She also is active in racial-justice organizing.

Emptying her trust fund proved to be an emotional process. “A certain amount of fear comes with giving it up,” she says. But ultimately “it’s really been transformational for me.”

Prier acted after tackling the tough questions that Resource Generation helps address: How much money do I need now, and how much will I need in the future? Do I need a car? Do I need to own a house, or is an apartment big enough? Prier lives modestly in a rented apartment and borrows friends’ cars when needed. She has some money in savings. She drew up a budget and gives away all that exceeds the amount she determined she needs.

Her family members are proud of her giving, and they also give — including to the Lenape tribe at Prier’s suggestion, she says. “I am in the process of having conversations with them to explain why I’m doing this and how I think about it,” she says. She’s optimistic about the good that can come from those conversations. “There’s a lot of potential for our family to acknowledge our history, and the shame and guilt that might come from that, and to heal,” she says. “There’s a lot of power in doing that.”

Not everyone in Resource Generation has uncommon wealth. Elizabeth Cooper ’12 doesn’t have an inheritance at the moment, though she might one day. Until recently, she was living in a collective house for low-income queer artists (she’s a dance and performance artist) in the Bay Area, where the fee for her room, which included rent, food, and utilities, was $755 a month. She has a coaching business and teaches meditation — neither of which pays very well. But she’s from a supportive family that is financially comfortable, and she has the freedom to pursue what she loves. “I have a lot of class privilege, and I recognize the power and privilege that comes from going to a place like Princeton,” she says.

“I’m on a journey of learning how to relate to money and privilege in a way that feels in alignment with my values,” she adds. “Unequal distribution of resources hurts my heart ... .”

Poole decided the way she could help was to become an investment adviser dedicated to working with clients with inherited wealth. In 2018, she co-founded Chordata Capital — its slogan is “Investment with a Backbone” (chordata refers to animals with a backbone). The firm’s stated goal is to make investments in organizations with an explicit commitment to racial and economic justice. Poole’s co-founder is Tiffany Brown, a veteran of nonprofits who comes from a working-class background and is biracial. Poole, who lives in Stockton, N.J., wanted to work with Brown because “we both think it’s crucial to do this work across class and across race,” she says.

Last year, the firm brought together 10 people who have inherited at least $1 million. The group spent nine months working together to trace the origins of their wealth, draw up investment priorities, and understand how their wealth is invested, which is often no easy task, as documents and ownership are often opaque. The participants are asking themselves hard questions and flouting the stigma of talking openly about money.

“A lot of people are frozen around money. They get stuck,” Poole says. “We upload their brokerage statements and ask, ‘Who have you looked at this with before?’ It’s intimate. But people are eager to have peers. It’s isolating to make these decisions.” A second group began its work in October.

With the aging and eventual death of the baby-boomer generation in coming decades, huge numbers of people will be inheriting money. A report by researchers at Boston College predicted that family members would inherit $36 trillion between 2007 and 2061.

The goal of Poole’s firm is to support racial justice by shifting investments to poor, black, and immigrant communities that historically have been locked out when it comes to raising capital. At the end of 2019, Chordata Capital had $18 million in assets under management. The company does not invest any of its clients’ money in the stock market. Choosing investments with a good return is not the goal for Poole’s investors. “They don’t want to keep getting wealthier and wealthier,” she explains. “They want to redistribute their wealth over time.”

To embody their commitment to racial justice, Poole and Brown collect the same salary, but Brown gets “what we are cheekily calling the racial wealth-gap bonus,” an addition to her salary to make up for historically unequal pay for African Americans, Poole explains.

Jess Conway ’09 and her husband, Justin Conway ’07, are among Poole’s clients. They didn’t know Poole at Princeton but began working with her in 2018 when they began actively managing an inheritance.

Jess was a teacher in public high schools for 10 years; she now is pursuing a Ph.D. in English education at Columbia University Teachers College while working as an instructor at Teachers College and at SUNY Orange, a two-year college near Beacon, N.Y., where they live. Justin is a sports-medicine doctor. The couple has long been engaged with social-justice issues. Having two children prompted them to grapple with pragmatic questions about how to redistribute the majority of their inheritance and invest the rest of it responsibly.

“We were really struck when we had our daughter with the ubiquitousness of the narrative that we should hoard wealth, that we should prepare financially for the unknown and the future of our future generations,” Jess Conway says. “When I think of what I want the world to be like for our kids, I have to think of everyone else’s kids too. Our future is a shared future. And what I really want to give our kids is a sense of community. Not a gated community, but real community.”

The Conways looked into socially responsible investing offered by traditional financial firms, which offer financial vehicles that focus on environmental and social causes. Socially responsible investing is soaring in popularity, according to a study released in 2018 by J.P. Morgan, which found that almost $23 trillion was invested worldwide in assets that bear that label. But those funds fail to address structural inequality, according to Jess Conway. Poole’s investment firm “is offering something at another level of thoughtfulness,” she says. The couple seeks investments in “black and Indigenous leadership, work led by women, and gender-queer and formerly incarcerated people.”

Poole told the couple about Hope Credit Union, based in the Mississippi Delta, which offers loans and other financial services in economically distressed areas of the Deep South. The mission resonated with Jess Conway, who is from Arkansas. The credit union finances community facilities and affordable housing and offers “transformational deposit rates,” which permit investors who buy a certificate of deposit to elect to get back a lower return — say 0.5 or zero percent — so that most or all of the investors’ profits go back into the credit union. The Conways chose zero percent.

That is the type of investment that appeals to Tessa Maurer ’13, who thought of herself as middle class until, as she was starting Princeton, her mother casually mentioned that Maurer had a trust fund. In 2018, she invested in the East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative, forgoing the dividend payment so her profits could go back into the cooperative.

Maurer, who is earning a Ph.D. in water resources and hydrology at Berkeley, is just starting to figure out what to do with her wealth, which comes from her Chinese grandparents, who fled the Communist Revolution to come to the United States. They had jobs in education — and a knack for frugality and savvy investments in the stock market. “I want to leverage the money to make society more just,” says Maurer, who is devoting much time to researching where to invest her money to do the most good.

The Conways also are deeply involved in researching ways to both invest and redistribute their funds. They work with several nonprofits in their community, such as Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson, in New York State’s Hudson Valley, which works on protections for undocumented immigrants. The Conways volunteer their time as well.

Many nonprofits that Jess Conway has studied, she says, are “Band-Aids that maintain a status quo of injustice.” In the 2018 book Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World, Anand Giridharadas compiles a litany of initiatives funded by elites who profess to be making significant efforts to help the needy. But these projects are merely giving elites the imprimatur of doing good while accomplishing little substantive change, he contends.

Leah Hunt-Hendrix *14, a granddaughter of Texas oil tycoon H.L. Hunt, discovered that dynamic for herself when she inherited wealth and became involved in philanthropy. Nonprofits “always feel pressure to appeal to the donor class to get work funded, and in that process they reframe what they are doing to appeal to those people,” who usually are not interested in radical social change, Hunt-Hendrix says. In 2012, she co-founded Solidaire, a community of donors who fund grassroots progressive social movements. Solidaire doesn’t ask for grant proposals or reports. Instead, members — who join for $15,000 — let each other know via an email listserv about worthy projects, and individuals send checks on their own. Organizers at Standing Rock — who were protesting a pipeline near the Sioux Reservation there — asked for funding in 2015 and have received at least $100,000 in contributions from Solidaire members each year since then, according to the nonprofit. “A traditional foundation wouldn’t touch protesters,” Hunt-Hendrix says. Last year, Solidaire members gave a total of about $5 million to nonprofits.

Like Hunt-Hendrix, Poole finds that sharing her wealth — and helping others share theirs — brings satisfaction. “There’s this myth that hoarding a certain amount of money will keep us safe or make us happy. Tiffany and I have seen that an extreme amount of wealth doesn’t buy happiness,” Poole says. “You can accumulate and give it to your kids and think it will create safety and happiness for them, but that’s not true if they are inheriting a world with extreme inequality. But investing in the community you want is transformative, and it can build the kind of world you want your children to inherit.”

To that end, in 2018 Poole made a $250,000 investment in a fund that strives to build black economic power through real-estate development, business incubation, and the arts. She connected with the leaders of the fund through a café they own that is near the synagogue where she celebrated her bat mitzvah. Last June, Poole spoke to the congregation about her investment.

“My family has been a part of this congregation for generations. My great-great-great-great grandfather Michael Simon Levy was a founder, so it’s a powerful and vulnerable moment for me to be sharing my life’s work with you today.

“I was raised to be generous, to seek justice, to be kind,” she said at the synagogue, Beth Am in Baltimore. But, she continued, she wasn’t taught to ask: How am I implicated? “The accumulation of wealth in this country is based on the theft of land from Native peoples, the kidnapping and enslavement of Africans, and policies and practices created by governments and financial institutions — like the Homestead Acts, the GI Bill, redlining, racist deed covenants, discriminatory lending practices — that built wealth for some at the expense of others.”

Poole’s investment, she told the congregation, was “the largest financial commitment of my life, with the wire going through last year on Juneteenth. I felt deeply grounded in the healing work of investing in black sovereignty and in building black-Jewish solidarity.”

The investment is the most meaningful one she has ever made, she says. “I wanted to fund work in the footprint of my ancestors’ accumulation of wealth,” she says. “For me, this is spiritually important.”

Jennifer Altmann is a freelance writer and editor.

Want To Get Involved?

Three things everyone can do to invest in racial and economic justice, recommended by Kate Poole ’09:

1. Bank locally: Move your money into local credit unions and banks grounded in your community. Local banks charge fewer fees, keep decision-making local, and put your money to work growing your local economy. Small banks and credit unions tend to turn deposits into loans and other productive investments.

2. Invest in Community Development Financial Institutions: CDFIs emerged out of the civil-rights movement to address historical discrimination in banking and lending. They provide access to financial services for working-class communities of color.

3. Learn about the history of our economy. Resources like The Princeton and Slavery Project, The New York Times’ 1619 Project, and The Movement for Black Lives policy platform provide information about the history and opportunities for repair and reparations.

10 Responses

Matthew D. Shapiro ’76

5 Years AgoThe Benefits of Philanthropy

I read “Reckoning With Wealth” in the March 4 issue of PAW and can only admire Kate Poole ’09’s commitment to putting her inherited wealth to charitable use. I also read Gaetano Cipriano ’78’s letter addressing Ms. Poole’s activities (Inbox, April 22) and, while I likewise admire Mr. Cipriano’s drive and persistence in “amassing a nine-figure net worth” through his own hard work, I’m shocked by the tone of his letter.

Reasonable people could diverge from Ms. Poole’s conclusion that inherited wealth should be spent for charitable ends rather than personal or familial ones. That is, and properly should be, the individual’s call to make. But feelings of guilt or simple ambivalence about inheriting great wealth that one did nothing personally to earn (Ms. Poole’s point) are an important driver of charitable largesse in our society, right up there with tax inducements, and charitable causes would be much the poorer without such motivation. And notably, in many cases charitable donations have the effect of lessening the burdens of government by helping to fund necessary services that would otherwise fall to governments — and hence taxpayers — to provide out of their own resources.

Since Mr. Cipriano’s description of his net worth suggests that he’s in a very high tax bracket, one would think he’d appreciate decisions like Ms. Poole’s to help lessen some of his potential tax burdens. But instead of welcoming such philanthropy, he vilifies Ms. Poole and the other charitable donors cited in the March 4 article with epithets like “spoiled brats” and “pathetic crybabies.” One can only wonder what life did to Mr. Cipriano to generate such wild invective against persons who have not only done him no harm but may, in fact, be benefiting him.

Dwight Sutherland ’74

5 Years AgoOn Wealth and Privilege

Philanthropy is best driven by a sense that to whom much is given, much is required. It can also be inspired by compassion and a desire to help the less fortunate. Shame and guilt are less praiseworthy motives, a point that appears to have eluded Matthew Shapiro ’76 in his defense of Kate Poole ’09’s quintessential white liberal guilt trip.

What Gaetano Cipriano ’78 and I find so offensive about Ms. Poole’s Neo-Marxist kvetching is that no one should use the opportunities and freedoms afforded us by our own system of democratic capitalism to destroy that system. Moreover, it is tiresome to hear wealth and privilege assailed by someone who would otherwise be ignored but for the platform afforded her by her unearned wealth and privilege. Trustafarians of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your Priuses!

William Parente ’64

5 Years AgoMissing the Point

I found the article on inherited wealth impressive and uplifting. The decisions by the group alumni to invest their inherited wealth in organizations working in the service of humanity should be commended, not mocked by the likes of Guy Cipriano ’78.

I could match Guy’s tales of work note for note beginning with starting work at age 12; painting houses during NYC summers; washing pots and pans in the kitchen of a day camp for rich kids; working in a machine shop with my father; installing telephones on the Lower East Side where I was chased by dogs and bitten by fleas. If I am incorrect I will admit the error, but I saw no mention in Guy's letter of military service. I would ask, have you ever stood watch in the Engine Room of a WWII era aircraft carrier where the temperature was 130 degrees; and where the only relief you might get was standing in front of a “blower” providing a stream of air which was also 130?

My point is, Guy you missed the point. When you use your socio-political economic views to make judgements, you forget the analytical skills you learned at Princeton and you are always wrong. The point is that those alumni have found the answer to a question you apparently missed. "How much do you need?" How many luxury cars, how many houses, how many suits, shirts, pairs of shoes; how many vacations?

When I graduated from Princeton I owed the University and Federal Govenment $1,000 each. When my wife accepted my proposal we had $600 between us and a 1965 Corvair on which I owed about $500. I was made an officer and a gentleman by an act of Congress and I earned an advanced degree from an Ivy League university with “distinction.” My wife and I worked our entire careers serving others in health care. We have a seven figure net worth; modest by your criteria but we know what we need, and after helping our children and grandchildren each year we give the rest away.

Clinton W. Kemp ’71

5 Years AgoThe Work of Oznot ’68?

With respect to “Reckoning with Wealth” (March 4 issue):

I cannot recall when last I read such a spectacular specimen of self-loathing, narcissistic, delusional drivel. At first, I thought the piece was an exercise in satire. Upon reflection, however, Princeton’s institutional arrogance makes satire an unlikely explanation. Then another possibility occurred to me: The article may in fact have been written by J.D. Oznot ’68. After all, Oznot is the only Princetonian I know of who might have put his name to a public display of such smug and arrogant nonsense.

Would the editor please clarify?

Steven Tobolsky ’76

5 Years AgoCharity and Ideology

I had not been aware of Resource Generation until I read “Reckoning With Wealth” in the March 4 issue of PAW. However, as a former private-school educator, I have worked with countless trust-fund babies on both sides of the cultural divide. They don’t all feel uncomfortable with their inherited wealth, nor is there any unequivocal scale of moral authority by which the rest of us may make judgments about how they should feel about it. And while I do not believe that wealthy individuals need necessarily feel guilty about anything, I certainly admire the principled behavior of young alums such as Kate Poole ’09. Surely the impulse to support charitable causes (regardless of ideology or politics) must be as above reproach as the freedom to pursue any other deeply held personal desire for fame or fortune.

Charles S. Rockey Jr. ’57

5 Years AgoIn Defense of the GI Bill

In an otherwise admirable article, “Reckoning With Wealth,” Kate Poole ’09 goes off the rails by attacking the GI Bill (the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944), which expired in 1956.

The bill provided low-cost loans to buy a house or start a business or farm, and payments to attend high school, college, or vocational school. By 1956, 7.8 million veterans had used the GI Bill’s educational benefits.

Historians and economists judge the GI Bill a major political and economic success, particularly compared to the shabby treatment of veterans after World War I.

Carrie Van Winkle

10 Months AgoGI Bill History

Mr. Rockey, it will only take a few minutes to read about how a million Black WWII Veterans were denied the benefits of the GI Bill. Link here: https://www.history.com/articles/gi-bill-black-wwii-veterans-benefits

Redlining in its various forms is well know and documented. No one said the GI Bill itself was a bad thing (my white grandfather, veteran of the Korean War, was a beneficiary of it). But we must understand how it was implemented with a racist lens to shut out certain qualifying and worthy candidates (WWII heroes) so that we do not continue to repeat the same mistakes (or similar mistakes in a modern form).

Gaetano P. “Guy” Cipriano ’78

5 Years AgoOn Work and Wealth

I read “Reckoning With Wealth” in PAW. Miss Poole must never have pumped gas in a blizzard or mixed mortar when it was 98 degrees in the shade, and there was no shade. I’ve been working since I was age 12, and I have amassed a nine-figure net worth without being a racist. The statement “wealth and racism are inextricably linked” is absurd on its face. I employ 150 highly paid, highly skilled people of every possible background. PAW needs to be considerably more demanding in its journalism because this piece is nonsense.

If some spoiled brats want to whine about their wealth, that’s not newsworthy. There are Princeton alumni doing real work, in the real capitalistic world, making this nation better every day. They are the people who should be celebrated and publicized, not these pathetic crybabies.

Adam Gussow ’79 *00

5 Years AgoYes, But...

I applaud PAW for shining a spotlight on the social justice work of Kate Poole ’09 and other white female millennials, beneficiaries of inherited wealth, who are determined to make our world a better place by rethinking their relationship to American history and their own familial history.

Although the word “white” only shows up once in the article, each of the half-dozen young women seems to be wrestling, some more painfully than others, with ideas about privilege in which white racial identity and money are intermingled in a way that produces racial guilt — guilt towards those understood to be Other, disprivileged, in need of reparative justice. That guilt demands not just good works, but expiation and a kind of purgation: the giving away of so much money, in the case of Megan Prier ’11, that she ends up having to “[borrow] friends’ cars when needed.”

In America’s Atonement: Racial Pain, Recovery Rhetoric, and the Pedagogy of Healing (2004), the African American educational theorist Aaron David Gresson III explores the way in which “racial pain,” as he terms it, is produced in individuals by the “voluntary or forced association with a ‘spoiled racial identity.’” Blacks have carried that burden for most of American history, he argues, but in our own era whites, including whites who volunteer for the assignment, are beginning to share in it. Even as I admire the desire of Poole, Prier, and their peers to make the world a better place, I see traces of that dynamic at work here — a desire, born out of white racial pain, for some form of restored white racial innocence, something that compensates for what is felt to be a spoiled racial identity. And that worries me.

In How It Feels To Be Colored Me (1928), Zora Neale Hurston shrugged off the pain that some might have presumed would attach to her own identity as an African American woman in that earlier era. “Someone is always at my elbow reminding me that I am the grand-daughter of slaves. It fails to register depression with me. Slavery is sixty years in the past. The operation was successful and the patient is doing well, thank you.” She contrasted her own insouciance with that of her “white neighbor,” whose own anxious subject position, one unnerved by black achievement and haunted by white guilt, she argued prophetically, “is much more difficult. No brown specter pulls up a chair beside me when I sit down to eat. No dark ghost thrusts its leg against mine in bed. The game of keeping what one has is never so exciting as the game of getting.”

I understand, and commend, the desire to make America a better place, one that lives up, in Dr. King’s words, to the true meaning of its creed. Thoughtful, enlightened investments are surely a part of that, as are other sorts of work that help bring beloved community into being. But the idea that “wealth and racism are inextricably linked,” an idea credited to Resource Generation — “part support group, part financial adviser” — and embraced to a greater or lesser extent by all the white female millennials profiled in PAW, is intellectual overreach: a progressive ideology that leans out beyond the tensed particulars of actual American lives within the deeply troubled horizons of American history, transforming itself into a theology that offers the possibility of racial redemption to those who hunger for that.

There’s certainly no need to keep all one has, in Hurston’s terms. (I give to causes deserving of support, including the Innocence Project and the Jazz Foundation of America.). But the game of getting, too, is exciting, and should be the province of all. As for giving “all the money away,” as Prier has in the case of her own trust fund: That seems crazy to me. She justifies it by arguing that she has records of her ancestors “stealing land from Indigenous peoples on the East Coast during the early days of colonization.” But other of her ancestors, the story notes, “fought against oppression,” helping slaves escape on the Underground Railroad and helping end the discriminatory practice of redlining. Good on them!

Vows of poverty have a long and noble history as a spiritual practice, of course. But that’s precisely my point: What is being engaged in by Prier is a kind of religious scourging, not — at least in my view — a just adjudication of one young woman’s actual relationship with the totality of her ancestry.

Poole’s Jewish great-great-great-great grandfather was an immigrant from Europe; although driven by an entrepreneurial hunger as a would-be straw hat manufacturer, he and his children also faced a panoply of exclusions, oppressions, and potential humiliations as he sought to climb the ladder. Poole is surely aware of these; if she’s not, I’d urge her to read Richard E. Fraenkel’s article “‘No Jews, Dogs, or Consumptives: Comparing Anti-Jewish Discrimination in Late Nineteenth-Century Germany and the United States.”

To judge not just from the article but from her Chordata Capital website, Poole is doing great work. Inspired work, in fact. But I think she, like Prier, is overinvested in the drama of compensating for the perceived sins of her ancestors. A little more forgiveness there — or even perhaps no forgiveness required, just simple gratitude for her ancestors’ achievements and bequests in the face of such discrimination — would go a long way toward delivering the peace and self-acceptance that are the predicate, I believe, for any effective movement for social justice.

Jody Johannessen ’86

6 Years AgoTrue Humility, True Service

To the young pioneers featured in this article, bravo for their vision, courage, and wisdom. I look forward to following their quietly methodical yet groundbreaking paths through the years. They inspire me with their humility and their ability to connect with organizations structured to give agency to those whom they serve.

Also, to the PAW editors, nicely done for highlighting alumni for their deeply thoughtful and selfless service.