Ask Sophal Ear *97 to tell you about himself, and he will first tell you about his mother, Cam Youk Lim. She was born into an ethnic Chinese family in Cambodia in 1936, left school after fourth grade, and lived with 11 family members, maids, a chauffeur, and other servants in a sprawling mansion owned by her brother-in-law in Phnom Penh. A quarter century of peace had ended in civil war in 1970, and in early 1975 the country was quickly moving from civil war to genocide. Then the Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot’s revolutionary army, marched into town. Lim, her pharmacist husband, and their children were dispatched to the countryside, along with anyone else with eyeglasses or soft hands or other signs of middle-class life. “We had no food or water, and soon we realized we were walking toward oblivion,” Lim recalled in 2005 — in a New York Times essay written with Sophal (pronounced “so-Paul”), her youngest son. “Sophal was an infant, and I could no longer nurse him. I tried to give him away so that he would have a better chance of survival, but everyone was as destitute and desperate as we were.”

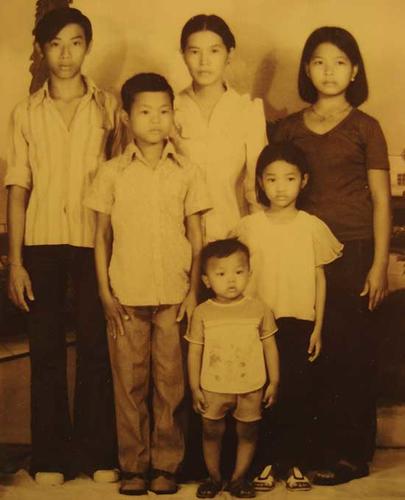

Two million people were driven from their homes. Lim and her family ended up in Pursat province, working the rice fields. “Having been raised in the city,” she notes, “my husband and I knew nothing about farming.” When her husband died of dysentery, Lim, then 39, was emboldened to try a novel escape strategy. The Khmer Rouge announced it would allow Vietnamese immigrants to return to Vietnam. Lim, who spoke a little Vietnamese, gave herself a new name, a new story, and a crash course in the language, helped by another woman fleeing Cambodia. For her interview with a Vietnamese official, Lim wrapped her children in blankets, made them pretend to be sick, and affected her best Saigon accent. Once across, she was given a can of milk to feed Sophal and sold her last ring to buy a pot of noodles and some pork fat. It was the family’s first real meal in six months.

Within three years, the family was in France. A cousin living there found someone with the same last name, and a sympathetic Frenchman forged signatures declaring a family relationship. Lim sewed fancy tablecloths with embroidered flowers and sewed her family back together. Then, after seven years, she packed up her youngest children to start a new life in the United States, first in Richmond, California, where yet another sister lived. She worked again as a seamstress, making wedding gowns for bourgeois brides and impressive outfits for her own children. She moved from Richmond to Oakland’s Chinatown, then to an apartment behind a garage — or as her son Sophal calls it, a “shack” — on the edge of one of Oakland’s leafy neighborhoods.

The life she lived is nothing like the life her son lives now. He is married, with four children, living the relatively comfortable life of an academic at Occidental College in Southern California.

But Cam Youk Lim and Sophal’s native Cambodia are never far from his thoughts. Her history, and Cambodia’s, inform the academic papers he writes and are woven through the speeches he has given at TED conferences and international agencies and economic groups. All his professional life he’s been pondering the unexpected consequences that can follow when people with grand, abstract ideals — from the Maoist precepts of the Khmer Rouge to the big-bucks projects of China or Western democracies — try to impose those ideals on vulnerable countries, wreaking havoc on the lives of people like his mother.

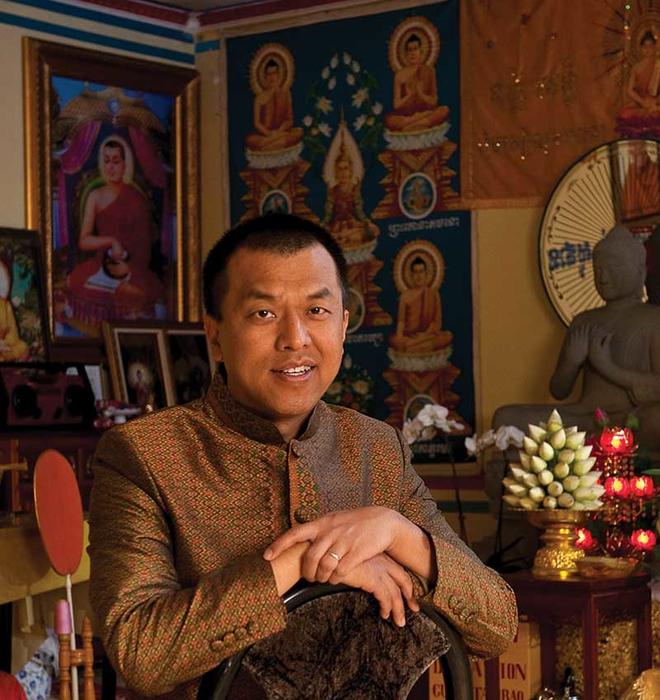

Sophal Ear is now an associate professor of diplomacy and world affairs at Occidental and a leading expert on Cambodia. He is an unlikely academic — a voluble introvert, a storyteller with a penchant for statistics, a professor as passionate as he is analytical, the son of a Buddhist who is proud of how far he’s come.

The late Cam Youk Lim surely would not have seen her life as a parable of resilience. And yet her son has taken her story of instinct, grit, hard work — and some critical family and social connections — and applied it to the world of international affairs. His body of research examines the impact of foreign aid on post-conflict countries, arguing fiercely that donors can actually impede the success of developing nations.

Long before he became a professor, Lim’s youngest son had developed his own version of his mother’s survival instinct — though the nightmarish images of his mother’s stories are replaced, in his, with self-deprecating humor. His earliest memory is of rolling around underneath the seats during the plane ride out of Vietnam to France, and he reports with glee that as a little boy he sang decent renditions of Vietnamese communist songs.

France invoked its own trauma for him, though. For two years, Sophal and his sister Sophie were taken in by separate French families and saw their mother only on weekends. He says his French family treated him like “the little prince,” but the weekly partings from his mother involved bawling, hiding under beds, and desperate pleas.

Education became an instrument of his salvation. When he was 10 and leaving France, Ear’s host family handed him an envelope. In it was a note and an old, medieval key, big enough, Ear says, “for a castle door.” In fact, it was the key to one of the family’s homes. The note said, “We love you and hope that you’ll go to les grandes universités americaines. If anything happens, if you should somehow need to return to France, you’ll always have a place back here.”

“I never wanted to use it,” Ear says. “I resolved to myself, no, I am not going back to France. I am moving forward in my life. I am going to go to the grand universities. I need to prove that I don’t need that lifeline.”

In Richmond, a lower-income suburb of San Francisco, Lim and her children moved in with her older sister. Ear entered school in the middle of seventh grade, as someone had determined — incorrectly — that it would match his grade level in France. He commuted to the city of Berkeley, more than an hour each way, alone, on BART trains and buses. “I went to Willard Junior High School, using a borrowed address and basically committing a crime,” he jokes, then admits that the experience was searing: “I didn’t speak English. I didn’t have friends. Everyone was two years older than me. They were taking about things I knew nothing about, like sex.”

The academics weren’t the problem — math was familiar, at least. But he was barely 11, Cambodian, with little English, bad teeth, and a tense home life. “I made friends, but then it turned out that those friends were making fun of me. ... It’s a kind of growing up that one has to do rather quickly.”

By the time Ear entered the renowned Berkeley High School, Lim had found a job at Elegance Embroidery in Oakland. “We were dirt poor,” he recalls. “We went to a food pantry. It was cold in the winter in that shack and hot in the summers. I was ashamed. There were so many occasions where it felt as though we didn’t have.”

High school was less traumatic, though. He got braces, his brother Sam paying the monthly installments. Although the family couldn’t afford to buy him an official school jersey with its yellow-jacket mascot, Lim embroidered facsimiles of the insect onto a jersey she designed for her son. “I felt like I was the bomb when I wore that,” Ear says.

Although English 1A was grueling, something clicked in a government class. “We simulated the U.S. government, and I wrote to Sen. Orrin Hatch of Utah. He wrote me back, or at least somebody wrote me back with an auto pen.” Ear started the Candid Republicans Club at school and joined the California Republican Party. “I wanted so much to fight communism at Berkeley High School,” he says, the irony delighting him. “After all, the Khmer Rouge had risen to power because of communism ... .”

He graduated with a 3.4 GPA (“nothing to write home about”) and was rejected by the University of California, Berkeley. A Vietnamese counselor who had taken Sophal under his wing steered him to a meeting at Berkeley’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies, where Ear met an administrator who wrote a letter of appeal. Ear entered Berkeley at 16.

He was a commuter — taking the bus from the “shack” to the university. Family pressure convinced him to be pre-med but he “barely dodged academic probation.” He decided on a different course one day in the lab. He “deeply believed in the American system,” he says. Political science appealed, and he added economics for a double major that seemed more respectable.

As a junior, he noticed a flyer for a summer program at the then-Woodrow Wilson School, which recruited people of color to address a diversity deficit in public policy. “I really wanted this experience,” he says, recalling his envy of the Southern California kids with their dorm lives and their college jerseys. He went for it.

When he arrived, he recalls, “Everybody, no matter how rich or poor, was issued the same stuff. You arrive and you’re all given textbooks, brand new. You’re all given scientific calculators. It was like this experiment run by social scientists except that there was no control group.” He fell in love with Princeton.

He returned to UC Berkeley to graduate and applied to the Woodrow Wilson School for a master’s degree. He calls Princeton his “finishing school,” though it was not the end of his education: He went on to earn a master’s degree in agricultural and resource economics and a Ph.D. in political science at Berkeley, after spending three years in the country of his birth, working on his dissertation, The Political Economy of Aid, Governance, and Policy-Making: Cambodia in Global, National, and Sectoral Perspectives.

That thesis was the beginning of a scholarly output that has been prolific. Ear now balances teaching, writing books, opining on Southeast Asia, walking seven miles a day, and being what his wife, Chamnan Lim, calls “an amazing dad” to his four children, ages 5 to 11. (Lim is also a Cambodian refugee.) Ear made the “Khmerican’s Must Watch Top 12” in 2012 and “40 Under 40: Professors Who Inspire” in 2015. His documentary, The End/Beginning: Cambodia, won a gold medal at a film festival. He is a TED Fellow and a Young Global Leader of the World Economic Forum. For street cred in the practice of political science, he served on the Crescenta Valley Town Council, representing more than 20,000 residents in an unincorporated area outside Los Angeles.

Ear calls himself an “accidental professor.” He prefers writing to speaking. “I’m an extremely introverted person who is forced to go on stage constantly,” he explains, likening himself to a wind-up doll with a string that, when pulled, sets him to delivering his well-practiced lines.

Ear applies lessons from Southeast Asia to developing nations around the world in his books, Aid Dependence in Cambodia and The Hungry Dragon, co-authored with Sigfrido Burgos Cáceres. (A new book, Viral Sovereignty and the Political Economy of Pandemics, is under review.)

Cambodia today is a society of haves and have-nots. Prime Minister Hun Sen and his ruling Cambodian People’s Party have stilled the chaos of war but installed repression and corruption. Despite large GDP growth rates, Cambodia continues to experience high infant mortality, spiking corruption, and a widening gap in wealth inequality. In the city there is a growing middle class, but in the country, agriculture has not pulled farmers out of poverty, and unexploded ordnance continues to kill and maim rural citizens. Sublime beauty and brutality continue to coexist.

Cambodia’s principal industries (textiles, shoes, bikes, and toys) have yet to be replaced by the manufacture of higher-value goods (electrical appliances, auto parts, and components). Potentially strong sectors in banking and finance have yet to blossom. Even Cambodia’s recent growth in tourism, which has fueled a new middle class, comes at a cost. “We cannot all be busboys and concierges,” Ear notes.

His prescription for Cambodia and similar small countries can be expressed in a list heavy on imperatives: Don’t become aid-dependent, don’t be seduced by autocracy, beware Kabuki democracy, invest in human development (health, education, nutrition, social protection), and be strategic about aid so that you are developing the industries you want to develop. If you’re manufacturing products, produce the elements that go into those products (not just assembling them for sale) to maximize the benefit of exports. If you’re an agrarian economy, invest in productivity.

Instead, in Cambodia, the government’s infatuation with real-estate development, especially tall buildings owned by foreigners (which Ear derides as a “phallic obsession”), means that resources are drained away from development that would benefit the general population. Cambodia has also become dependent on China for funding infrastructure like dams, roads, and factories, all of which has made China Cambodia’s largest creditor, accounting for up to 44 percent of the $19.2 billion in foreign direct investment between 1994 and 2014.

Ear focuses his wrath, and his analytical passion, on donors, maintaining that international aid distorts Cambodia’s economy by preventing sustainable development, fostering corruption, and disrupting the link between taxpayers and their government. Assistance and investment from China, which Ear calls “the Hungry Dragon,” carries particular risks, including financial reward for China and a tolerance of the authoritarian regime.

Echoing Ear, journalist Jon Swain sees China as “a hungry neighbor” and notes that “vast tracts of land have been corruptly sold off to Chinese businessmen for development and the proceeds pocketed by Hun Sen’s cronies.” Swain, in a 2020 essay on Cambodia in the book Imagine: Reflections on Peace, writes of the stark contrast between a sparkling new Chinese resort and a crowded Cambodian shantytown nearby. “The Chinafication of Cambodia looks unstoppable,” notes Swain, calling such scenes “the latest example of how this small and weak country has been undermined by a powerful foreign state.”

For his part, Ear has called Cambodia “a kleptocracy cum thugocracy” and has added that the international community, led by the UN, “is its enabler.” The people don’t pay enough taxes, what they do pay is stolen by a corrupt government, and the government doesn’t listen to them. All of this has landed Cambodia on lists of the most corrupt countries in the world. “What do you have? he asks. “Pretend democracy.”

Ear’s theories extend as well to public health. In his next book, about viral sovereignty, Ear examines how developing nations can avoid being at the mercy of developed nations, whose “rampant vaccine nationalism has created unsustainable and unethical practices.” He looks at the example of the avian flu, where viral samples were extracted from Indonesia by other countries, to make vaccines for their own citizens and to sell them back to Indonesia at exorbitant prices. Developing countries, he argues, should collaborate and stand up to medical powerhouses like the U.S. and Russia. The COVID-19 pandemic acts as an alert; developing countries must build their own capabilities to create diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines.

Ear’s arguments are bound to his personal history. He understands vulnerability as deeply as he does success. His mother struggled through post-traumatic stress and was hospitalized in France; despite her support, his degrees, and his prestigious positions, Ear has grappled with self-doubt and depression. At almost every step, he says, he has felt in over his head and wracked with questions. “We refugees cannot seem to escape the idea that wherever we are, we better be ready for that knock on the door. Oh, my God, it’s time to go. Be ready, nothing is as good as it seems.”

Then, he says, “as I survive those first few months and nothing happens, I say, ‘OK, I made it through. My mother and I and my siblings escaped the Khmer Rouge. So whatever happens after that cannot be anywhere near as bad, right?’ It doesn’t sound optimistic, but it certainly is what tells me that it’s never as bad as it seems. That I can go on, that we will be fine.”

Ear is fond of quoting the Talmud: “Whoever saves a single life is as if one saves the entire world.” And he notes a related Chinese proverb: “Whoever saves a life is responsible for that life.” He says he believes his late mother is responsible for all her children’s and grandchildren’s lives, and to cement that legacy, he wrote and narrated a documentary based on the eulogy he gave at her funeral, a letter to her grandchildren.

Although he initially feared that talking about his own experience would undermine his work — that refugees in particular might equate personal struggle with a loss of respect from colleagues — he has found talking about his past liberating. “I’ve embraced my inner Cambodian,” he says, and he believes he can “show others that there is hope.” He adds that as one of a small number of Cambodian academics with Western Ph.D.s, he has a responsibility to critique the regime there, even at some personal risk. He dreams of returning to Cambodia in an official capacity but has been singled out by Hun Sen for disparagement. For Ear, such attention precludes even visiting today.

“I have felt a calling,” he says, both wistful and determined. “It is my duty, even as an academic, to comment about Cambodia, to do things to help Cambodia, even if I’m on the outside. You can take the boy out of Cambodia, but you can’t take Cambodia out of the boy.”

Constance Hale ’79 is a journalist in California and the author of six books, including Sin and Syntax, a primer on language and literary style.

No responses yet