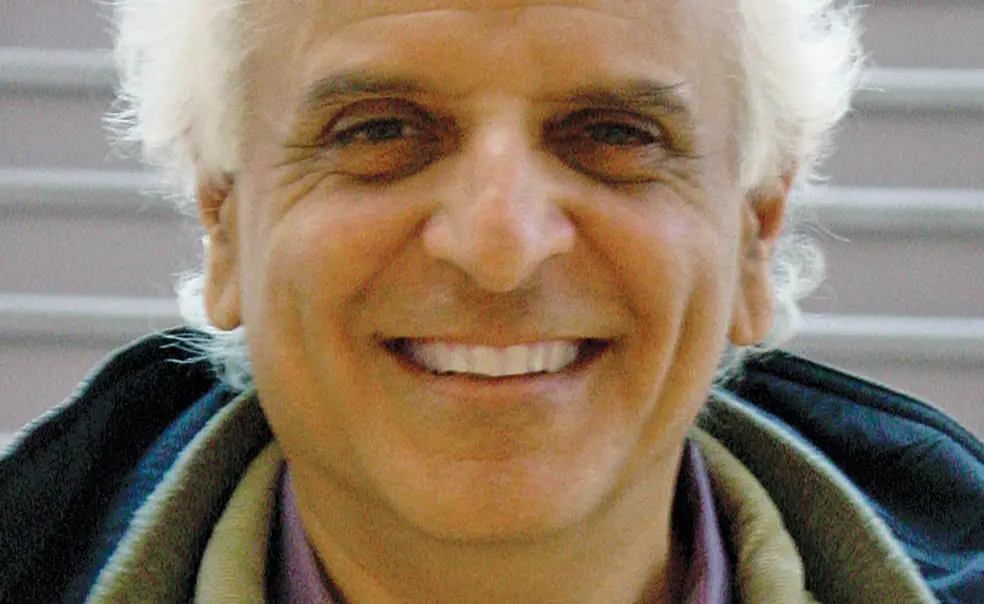

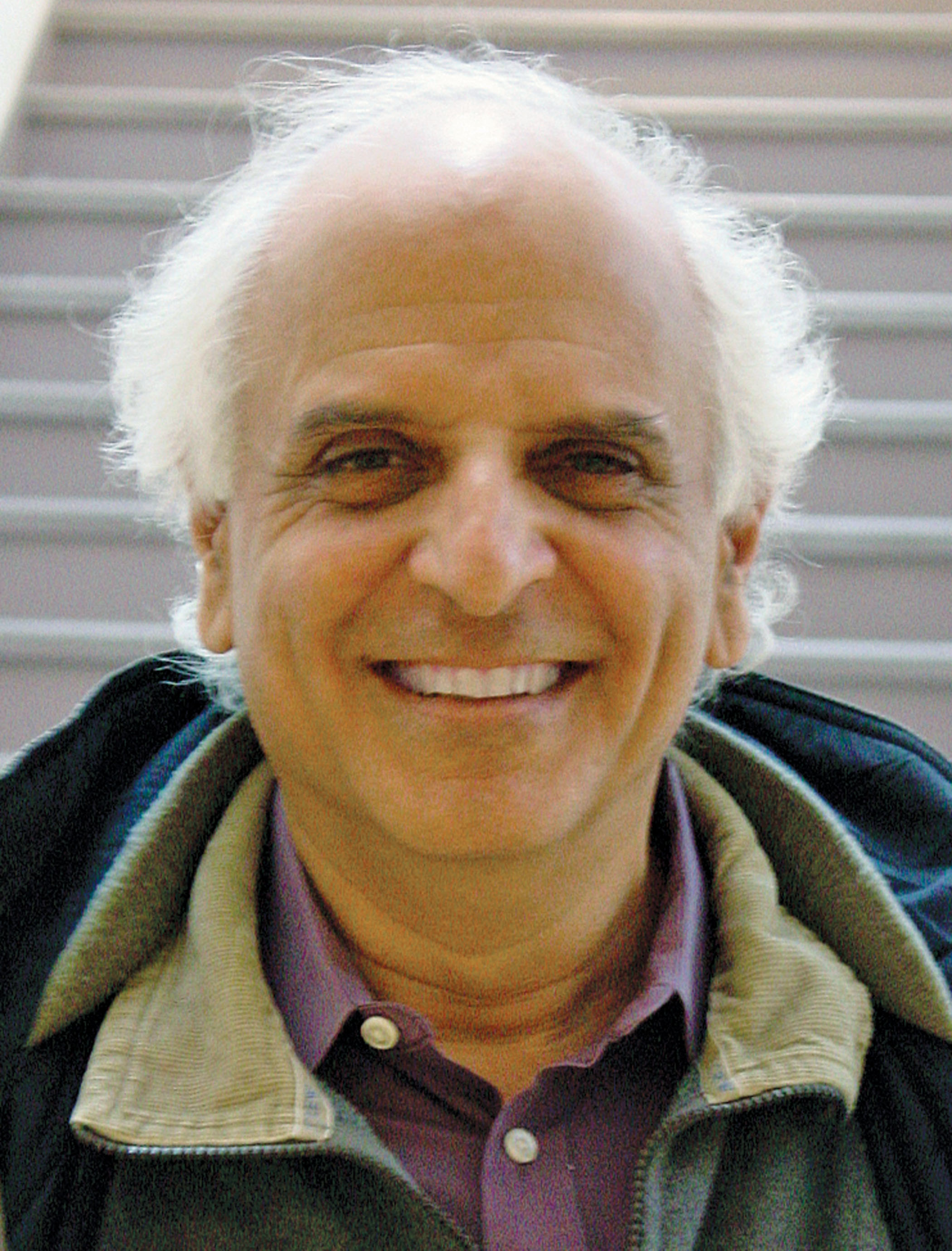

Reinventing himself

Composer Paul Lansky *73 is finished with electronic music and moves on to ‘real’ instruments

At age 64, Paul Lansky *73 is starting over. A pioneer in computer music, he has spent more than 30 years using a computer as an instrument to create music and to capture and model sounds from everyday life — the clatter of pots banging, the sound of traffic, the rhythm of a human voice.

But today, he says, he is leaving computer music behind and rediscovering the potential of the violin, the piano, and the symphony orchestra. “I had the feeling with electronic music after 30 or 40 years that I was struggling to uncover new territory. And writing for instruments, I find that I discovered 40 acres of territory that’s not been planted,” says Lansky, a Princeton professor of music who joined the faculty in 1969. He’s going through what he has called his “second compositional childhood” and “discovering new music in myself” that he couldn’t express using only electronic means.

Last month the Meehan/Perkins Duo performed his “Travel Diary” for two percussionists in Taplin Auditorium; the duo will perform it again Jan. 16 at Carnegie Hall’s Weill Recital Hall.

Lansky’s transition began slowly in the mid-1990s when, at the urging of several instrumentalists, he started writing solo pieces for them. Up to that point, Lansky estimates, 90 percent of his work was for computers. He wrote his first piece for orchestra two years ago — something he never had imagined doing, says Lansky, who had played the French horn with orchestras as a teenager. In the booklet accompanying Etudes and Parodies, his first solo CD of exclusively instrumental music (featuring works for a French horn, violin, and piano trio; solo guitar; and a string quartet) released last year by Bridge Records, he wrote, “I was comfortable, successful, and imagined sailing happily into senior citizenship doing nothing more than sitting at home in my bathrobe crafting sounds on my computer.” But as he started composing for violin and guitar, he wrote, “I began to revel at the miracle: My job was just to put little dots down on a page and these gifted performers would generate incredible results, sounds and spectra that I could never get on the computer.”

Known for using his computer as an “aural camera,” recording and then manipulating sounds from the real world, Lansky has used speech in many of his electronic works. In “Small Talk,” for example, he recorded a conversation between himself and his wife, and manipulated the sounds of the voices — focusing on the pitch, rhythm, and emotional content while filtering out the content of the conversation.

Lansky likens the role of a computer-music composer to that of a filmmaker — when someone listens to a piece, the composer is both creator and performer. And that control is, in part, what attracted him at the start. But it’s the very lack of control over the final product that has Lansky excited these days. “When you put notes down on a page for somebody else to follow, you’re expecting them to do things that you have no control over. That’s an exhilarating experience to have someone else step into the process.”

As for his well running dry on electronic music, he says, “I think it’s good for people to reinvent themselves. You always suffer if you rely too heavily on things that you know how to do well.”

No responses yet