In August 2011, Syrian security agents raided a private home in Aleppo, the country’s largest city, and arrested activists who had been using Facebook — posting with fake names — to plan meetings and demonstrations in the ongoing uprising against syrian president Bashar al-Assad. The protesters were detained for weeks. They had been working with Princeton doctoral candidate and Syrian native Karam Nachar, who — when he’s not working on his dissertation — is one of the uprising’s most prominent cyberactivists, spending hours on Skype to vet protesters hoping to join several secret Facebook groups he manages and weeding out potential operatives of Assad’s regime.

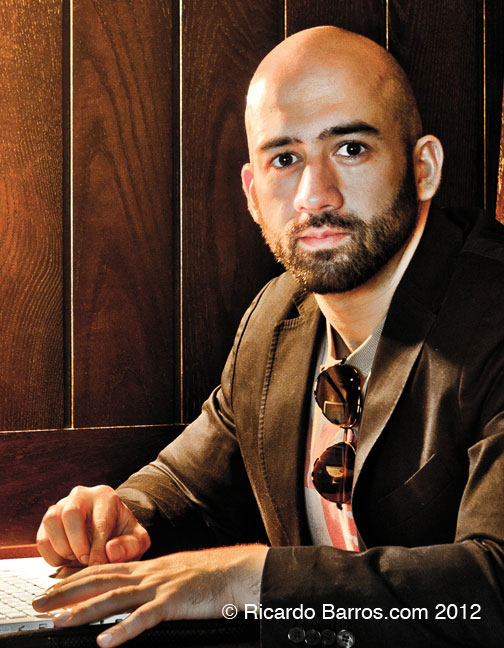

A few months later, Nachar is recalling the horrible day from a far safer place: a Starbucks across from Columbia University in Manhattan. Around him, students line up to purchase lattes and cappuccinos; the shop has a pleasant, peaceful air. Nachar is not thinking of pleasantries, however. “One of my good friends got arrested and was savagely tortured. I felt awful,” he says. “This is something we activists abroad think about. There’s always this guilt we have that no matter how much we pay in our daily life — in terms of not getting our jobs or studies done — ultimately, we’re not going to be arrested, tortured, or killed. Whereas people inside Syria, they are paying a huge price.”

FOR MORE THAN A YEAR, Nachar, 29, has been living something of a double life. He is working on a dissertation, due in the spring of 2013, which investigates the extent to which Beirut from the 1920s to the 1950s served as the Middle East’s incubator of intellectualism and religious tolerance. He teaches a precept class to Princeton undergraduates on European history, and moonlights at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York, teaching a class on the modern Middle East.

But much of his time is focused on events that are less rarified and more dangerous than academia — the uprising that began in March 2011 in which more than 9,000 people are believed to have died. Nachar is part of a passionate community of ex-pat Syrians who are hoping that the Arab Spring that swept through Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya will bring the downfall of the Assad regime and its brutal military. Syrian-Americans have been raising money for their countrymen, providing aid directly to rebels on the ground, and rallying in March at the White House to exert pressure on the Obama administration to intervene militarily.

Nachar and his circle of activists consider themselves part of the opposition umbrella group the Syrian National Council. They do not align themselves with any particular subgroup, though they espouse more secular and liberal views than many others who want to remove Assad from power. They argue for a multiparty, democratic government led by representatives chosen in general elections; separation of church and state; and equal rights for women and minorities.

Nachar’s father, Samir Nachar, is a former car-parts importer now living in Turkey, where he is helping to run the Syrian National Council — a role the son knows has placed the family on the radar of the Syrian government. The council has been praised by experts as the country’s best chance to unify the sectarian opposition groups, but also criticized for having weak relationships with some minority groups and the Free Syrian Army, formed by exiled Syrian military members and defectors.

Nachar admires his father’s work, but has chosen a different role for himself — in social media. He uses the secret Facebook groups to plan rallies, screen new members, and determine what activists in Syria need. In March, for example, Nachar was trying to raise money for a blood-clotting medicine made in the United States to ship to Syrian rebels. He also acts as a kind of U.S.-based media spokesman for the insurgency movement, speaking on MSNBC, Al-Jazeera, and the independent news program Democracy Now!, and to The Huffington Post and other outlets. He helps translate and write subtitles for activists’ YouTube videos for the BBC.

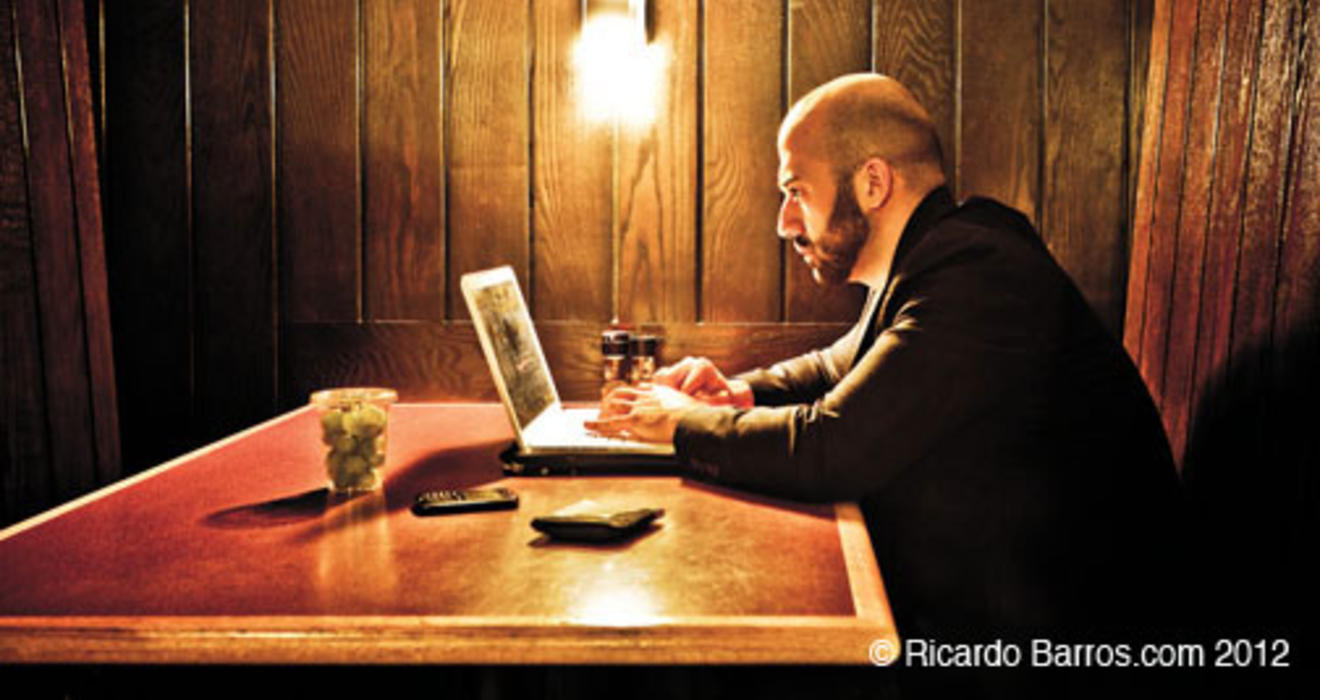

Every Sunday, he conducts meetings via Skype with activists around the world from his New York apartment. He often wakes up before dawn to read the latest media dispatches from the war zone. He scans Facebook and Twitter and blasts out links to videos or antigovernment rallies or dashes off opinions about his countrymen’s struggles.

Two of Nachar’s tweets (@knachar) in late March — he has about 600 followers — show him straddling his academic and activist lives: “Syria hasn’t had real political life in more than 50 years, thus the ‘opposition’ is nothing but a political class in ‘formation,’” he wrote March 17. A week later, he tweeted: “Running late to class. I think I can write a book now on the clash between activism and teaching! Sigh #syria.” He acknowledges that his dissertation adviser wishes he would spend more time on his academic work.

“People of Middle Eastern origin who have been watching all these events — it’s really going to put their academics on hold,” says Professor Amaney Jamal, the director of Princeton’s Workshop on Arab Political Development. When Jamal was organizing a campus panel discussion about the Syrian unrest in February, she struggled to find someone on campus with deep ties to Syria, then learned about Nachar from another faculty member and extended an invitation to him to participate.

“In the panel, he was able to get us into the heads of the opposition — things you’re not necessarily going to pick up from CNN,” Jamal says. “One of the most interesting things he said was that, for the longest time, the opposition had not been looking for Western intervention because it would hurt the legitimacy of the movement. But Karam hinted that if things got worse, the opposition was willing to work with Western powers.”

For his outspokenness, Nachar says he has received “threats from random people on Facebook saying I was a traitor” and that he was being “brainwashed by Americans.” But he sounds dismissive, and says he never has faced imminent danger.

NACHAR’S PATH IN LIFE seemed almost predestined. He grew up in Aleppo, near the Turkish border, and was raised by parents who hosted political debates and salons in their home or his father’s office. After Assad took power in 2000 from his dictatorial father, many Syrians hoped the country would transform into a more democratic society. But in March 2011, after some students had been tortured for putting up antigovernment graffiti, residents began protesting, and Assad’s security forces initiated a bloody crackdown, which ultimately triggered a national uprising.

After finishing high school in Syria, Nachar left his country in 2000 to study political science at the American University of Beirut, and graduated in the spring of 2003. Later that year, he began a one-year master’s program in modern Middle East studies at St. Antony’s College at Oxford University, a place that inspired him because it had been the academic home of the late Albert Hourani, an influential Middle East historian credited with training several prominent academics.

“I read several of Hourani’s books in classes, and he just moved me, because he wrote about modernizing and intellectualizing the Arab world. I grew up in a household interested in intellectual questions, a liberal family in a conservative society under an authoritarian regime,” Nachar says. “Between 2001 and 2005, my dad got arrested three times. He’d be in his office, and security agents would arrest everyone. It’s a joke what they would charge him with, like ‘secret plotting against the state.’”

In 2004, after completing a thesis on Egyptian intellectuals and earning his master’s degree, Nachar did a research stint at a publishing house in Beirut, which swung him back to the ivory tower. He wanted to write a dissertation on Middle East intellectual life, and looked at schools with top history departments. In 2006, he started at Princeton. “The history department at Princeton was very clear that you should broaden your perspective and take classes in other regions,” he says. “I’ve already lived in the Middle East, so I wanted to know more about Europe and Africa. It helps me understand how the Middle East is evolving in a bigger world.”

In 2009, he launched an 18-month dissertation-research trip to Beirut, where he interviewed members of families that had lived there between the 1920s and 1950s. He returned to Princeton in early 2011, just as the Syrian uprising was getting under way. Work on his dissertation slowed.

“I’ve only written two chapters,” he says. “It’s a daily struggle. You need a lot of focus. ... You have to sit and be on your own, and think about each chapter. I hardly sleep. I wake up at 4 a.m. I go to bed at 9 p.m. And I wake up in the middle of the night to see what’s going on.”

Samir Nachar feels proud of his son.

“He has to make a great sacrifice in putting his Ph.D. aside for several months, and it’s not an easy choice for him, but the Syrian revolution comes once in a lifetime,” he says via Skype from Istanbul, where he lives with his wife, Nouran, and their eldest child, 31-year-old daughter Zein Nachar. (In the conversation with PAW, Zein acted as a translator.) “Obviously we all prefer if he could stay in Syria and continue his work from inside, but there’s a huge role for the Syrian diaspora movement. Thanks to them, the world can see what the revolution is all about.”

Deep down, though, Karam Nachar knows that operating as a social-media maven never will put him on the front lines. He still is haunted by what happened to the friend in their Facebook group who was arrested and beaten in August. The police, armed with printouts of the Facebook group’s discussions, tried for two months to press Nachar’s friend into revealing the real names of the group’s members. The friend gave up only one: Karam Nachar.

After the young man was released, he called Nachar to apologize, telling him that he provided the name to stop the beating. Nachar doesn’t blame him — he figures that the government knew about him already because of his family connections. “I feel bad for him,” he says of his friend. “The fact that he confessed my name doesn’t bother me that much. I feel he did the right thing, if confessing my real name would have alleviated his suffering.”

Ian Shapira ’00 is a reporter at The Washington Post.

No responses yet