I knew the day would come, but I didn’t know how it would happen, where I would be, or how I would respond. It is the moment that every black parent fears: the day their child is called a nigger.

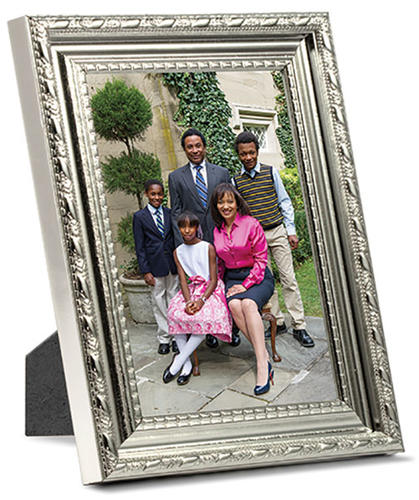

My wife and I, both African-Americans, constitute one of those Type A couples with Ivy League undergraduate and graduate degrees, who, for many years, believed that if we worked hard and maintained great jobs, we could insulate our children from the blatant manifestations of bigotry that we experienced as children in the 1960s and ’70s. We divided our lives between a house in a liberal New York suburb and an apartment on Park Avenue, sent our three kids to a diverse New York City private school, and outfitted them with the accoutrements of success: preppy clothes, perfect diction, and that air of quiet graciousness. We convinced ourselves that the economic privilege we bestowed on them could buffer these adolescents against what so many black and Latino children face while living in mostly white settings: being profiled by neighbors, followed in stores, and stopped by police simply because their race makes them suspect.

But it happened nevertheless in July, when I was 100 miles away.

It was a Tuesday afternoon when my 15-year-old son called from his academic summer program at a leafy New England boarding school and told me that as he was walking across campus, a gray Acura with a broken rear taillight pulled up beside him. He continued along the sidewalk, and two men leaned out of the car and glared at him.

“Are you the only nigger at Mellon Academy*?” one shouted.

Certain that he had not heard them correctly, my son moved closer to the curb, and asked politely, “I’m sorry; I didn’t hear you ... ”

But he had heard correctly. And this time the man spoke more clearly. “Only ... nigger,” he said with added emphasis.

My son froze. He dropped his backpack in alarm and stepped back from the idling car. Within seconds, the men floored the sedan’s accelerator, honked the horn loudly, and drove off, their laughter echoing behind them.

By the time he recounted his experience a few minutes later, my son was back in his dorm room, ensconced on the third floor of a four-story, redbrick fortress. He tried to grasp the meaning of the story as he told it: why the men chose to stop him, why they did it in broad daylight, why they were so calm and deliberate. “Why would they do that — to me?” he whispered breathlessly into the phone. “Dad, they don’t know me. And they weren’t acting drunk. It’s just 3:30 in the afternoon. They could see me, and I could see them!” My son rambled on, describing the car and the men, asking questions that I couldn’t completely answer. One very clear and cogent query was why, in Connecticut in 2014, grown men would target a student, who wasn’t bothering them, to harass in broad daylight. The men intended to be menacing. “They got so close — like they were trying to ask directions. ... They were definitely trying to scare me,” he said, as I interrupted.

“Are you okay? Are you —”

“Yeah,” he continued anxiously. “I’m okay. I guess. ... Do you think they saw which dorm I went back to? Maybe I shouldn’t have told my roommate. Should I stay in my dorm and not go to the library tonight?”

Despite his reluctance, I insisted that he report the incident to the school. His chief concern was not wanting the white students and administrators to think of him as being special, different, or “racial.” That was his word. “If the other kids around here find out that I was called a nigger, and that I complained about it,” my son pleaded, “then they will call me ‘racial,’ and will be thinking about race every time they see me. I can’t have that.” For the next four weeks of the summer program, my son remained leery of cars that slowed in his proximity (he’s still leery today). He avoided sidewalks, choosing instead to walk on campus lawns. And he worried continually about being perceived as racially odd or different.

By the time he recounted his experience a few minutes later, my son was back in his dorm room, ensconced on the third floor of a four-story, redbrick fortress. He tried to grasp the meaning of the story as he told it: why the men chose to stop him, why they did it in broad daylight, why they were so calm and deliberate.

Herein lay the difference between my son’s black childhood and my own. Not only was I assaulted by the n-word so much earlier in life — at age 7, while visiting relatives in Memphis — but I also had many other experiences that differentiated my life from the lives of my white childhood friends. There was no way that they would “forget” that I was different. The times, in fact, dictated that they should not forget; our situation would be unavoidably “racial.” When we moved into our home in an all-white neighborhood in suburban New York in December 1967, at the height of the black-power movement and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil-rights marches, integration did not — at all — mean assimilation. So my small Afro, the three African dashiki-style shirts that I wore to school every other week, and the Southern-style deep-fried chicken and watermelon slices that my Southern-born mother placed lovingly in my school lunchbox all elicited surprise and questions from the white kids who regarded me suspiciously as they walked to school or sat with me in the cafeteria. After all, in the ’60s, it was an “event” — and generally not a trouble-free one — when a black family integrated a white neighborhood. Our welcome was nothing like the comically naïve portrayal carried off by Sidney Poitier and his white fiancée’s liberal family members in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, which had opened the very month that we moved in.

It wasn’t about awkward pauses, lingering stares, and subtle attempts of “throwing shade” our way. It was often blatant and sometimes ugly. Brokers openly refused to show houses to my parents in any of the neighborhoods that we requested, and once we found a house in The New York Times Sunday classifieds, the seller demanded a price almost 25 percent higher than listed in the paper. A day after Mom and Dad signed the contract, a small band of neighbors circulated a petition that outlined their desire to preemptively buy the house from the seller to circumvent its sale to us. My parents were so uncertain of this new racial adventure that they held onto our prior house for another four years — renting it on a year-to-year lease — “just in case,” as my mother always warned, with trepidation on her tongue.

Referred to as “that black family that moved onto Soundview,” we never quite felt in step with our surroundings. A year after moving in, my 9-year-old brother was pulling me down our quiet street in his red-and-white Radio Flyer wagon when we were accosted by a siren-screaming police car; an officer stepped out shouting, “Now, where did you boys steal that wagon?” Pointing breathlessly to our house a few yards away, we tried to explain that it was my brother’s new wagon, but the officer ushered us into the back seat. Our anguished mother heard the siren and ran across three lawns to intervene. What I remember most is how it captured the powerlessness and racial isolation that defined our childhood in that neighborhood.

We never encountered drawn or discharged guns like those faced by unarmed black teenagers Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Fla., or Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. But I was followed, stopped, and questioned in local stores and on local streets frequently enough that I wondered whether my parents would have been better able to protect us from these racial brushes had they been rich, famous, or powerful — or if they had been better acquainted with the white world in which they immersed us. Perhaps I was naïve to think that if they had been raised outside segregated Southern neighborhoods and schools, they would have been better able to help us navigate the life we were living. In the 1970s, I imagined that the privileged children of rich and famous blacks like Diana Ross, Bill Cosby, or Sidney Poitier were untouched by the insults and stops that we faced. Even though the idea wasn’t fully formed, I somehow assumed that privilege would insulate a person from discrimination. This was years before I would learn of the research by Peggy McIntosh, the Wellesley College professor who coined the phrase “white male privilege” to describe the inherent advantages one group in our society has over others in terms of freedom from discriminatory stops, profiling, and arrests. As a teenager, I didn’t have such a sophisticated view, other than to wish I were privileged enough to escape the bias I encountered.

And that was the goal we had in mind as my wife and I raised our kids. We both had careers in white firms that represented the best in law, banking, and consulting; we attended schools and shared dorm rooms with white friends and had strong ties to our community (including my service, for the last 12 years, as chairman of the county Police Board). I was certain that my Princeton degree and economic privilege not only would empower me to navigate the mostly white neighborhoods and institutions that my kids inhabited, but would provide a cocoon to protect them from the bias I had encountered growing up. My wife and I used our knowledge of white upper-class life to envelop our sons and daughter in a social armor that we felt would repel discriminatory attacks. We outfitted them in uniforms that we hoped would help them escape profiling in stores and public areas: pastel-colored, non-hooded sweatshirts; cleanly pressed, belted, non-baggy khaki pants; tightly-laced white tennis sneakers; Top-Sider shoes; conservative blazers; rep ties; closely cropped hair; and no sunglasses. Never any sunglasses.

No overzealous police officer or store owner was going to profile our child as a neighborhood shoplifter. With our son’s flawless diction and deferential demeanor, no neighbor or playdate parent would ever worry that he was casing their home or yard. Seeing the unwillingness of taxis to stop for him in our East Side Manhattan neighborhood, and noting how some white women clutched their purses when he walked by or entered an elevator, we came up with even more rules for our three children:

1. Never run while in the view of a police officer or security person unless it is apparent that you are jogging for exercise, because a cynical observer might think you are fleeing a crime or about to assault someone.

2. Carry a small tape recorder in the car, and when you are the driver or passenger (even in the back seat) and the vehicle has been stopped by the police, keep your hands high where they can be seen, and maintain a friendly and non-questioning demeanor.

3. Always zip your backpack firmly closed or leave it in the car or with the cashier so that you will not be suspected of shoplifting.

4. Never leave a shop without a receipt, no matter how small the purchase, so that you can’t be accused unfairly of theft.

5. If going separate ways after a get-together with friends and you are using taxis, ask your white friend to hail your cab first, so that you will not be left stranded without transportation.

6. When unsure about the proper attire for a play date or party, err on the side of being more formal in your clothing selection.

7. Do not go for pleasure walks in any residential neighborhood after sundown, and never carry any dark-colored or metallic object that could be mistaken as a weapon, even a non-illuminated flashlight.

8. If you must wear a T-shirt to an outdoor play event or on a public street, it should have the name of a respected and recognizable school emblazoned on its front.

9. When entering a small store of any type, immediately make friendly eye contact with the shopkeeper or cashier, smile, and say “good morning” or “good afternoon.”

These are just a few of the humbling rules that my wife and I have enforced to keep our children safer while living integrated lives. For years, our kids — who have heard stories of officers mistakenly arresting or shooting black teens who the officers “thought” were reaching for a weapon or running toward them in a menacing way — have registered their annoyance at having to follow them. (My 12-year-old daughter saw the importance of the rules when, in late August, she and I were stopped by a county police officer who apparently was curious about a black man driving an expensive car. He later apologized.)

Not many months ago, my children and I sat in the sprawling living room of two black bankers in Rye, N.Y., who had brought together three dozen affluent African-American parents and their children for a workshop on how to interact with law enforcement in their mostly white communities. Two police detectives and two criminal-court judges — all African-American — provided practical suggestions on how to minimize the likelihood of the adolescents being profiled or mistakenly Tasered or shot by inexperienced security guards or police officers. Some of the parents and most of the kids sat smugly, passing around platters of vegetables and smoked salmon — while it helped to have the lessons reinforced by police officers, we had all heard it many times before.

My kids and I had it all figured out.

Or so we thought.

No overzealous police officer or store owner was going to profile our child as a neighborhood shoplifter. With our son’s flawless diction and deferential demeanor, no neighbor or playdate parent would ever worry that he was casing their home or yard.

The boarding-school incident this summer was a turning point for us — particularly for my son and his younger siblings. Being called a nigger was, of course, a depressing moment for us all. But it was also a moment that helped bring our surroundings into clearer focus. The fact that it happened just days before the police shooting of Michael Brown increased its resonance for our family. Our teenage son no longer makes eye contact with pedestrians or drivers who pass on the street or sidewalk. He ceased visiting the school library this summer after sundown, and now refuses to visit the neighborhood library, just one block away, unless accompanied. He asks us to bear with him because, as he explains, he knows that the experience is unlikely to happen again, but he doesn’t like the uncertainty. He says he now feels both vulnerable and resentful whenever he is required to walk unaccompanied.

It also was a lesson for us to grasp that some white men may believe such acts are really no big deal. I called a dean at the boarding school, who seemed to justify the incident as something that “just happens” in a place where “town-and-gown relations” are strained, but he had little else to say. My son’s school adviser never contacted me about the incident, acting with the same indifference that so many black parents have come to expect. After I reached out to them, I never heard from either man again. Like so many whites who observe our experiences, these two privileged white males treated the incident like a “one-off” that demanded no follow-up and that quickly would be forgotten.

Through no fault of their own, many white men, I think, are unaware or unappreciative of the white male privilege that they enjoy every day, which Wellesley’s Professor McIntosh wrote about in her studies of race, gender, class, and privilege. They have no idea how much they take for granted, or know of the burdens endured daily by many people in their own communities. Nor do they appreciate the lingering effects of such burdens and daily traumas. Perhaps many feel that racism is inconsequential, if not altogether dead. After all, as some of my white colleagues have pointed out cynically, how much racism can there be if the country elected a black president?

Let me say that to acknowledge that white male privilege exists does not mean that white privileged men are hostile or racist — or that all bad things that happen to black people are occurring only because of racial bigotry. But I am no better able to explain the lackadaisical response of the two white men to whom I reported the incident than I am able to explain the motives of the two white men who called my son a nigger in the first place.

And perhaps this is why it is so difficult to fairly and productively discuss the privilege (or burdens) that are enjoyed (or endured) by groups to which we don’t belong. Try as I may to see things from the perspective of a white person, I can see them only from the experience that I have as a black man and had as a black boy. As we observe each other and think that we have a close understanding of what it means to be black, white, Hispanic, Asian, male, female, rich, or poor, we really don’t — and very often we find ourselves gazing at each other through the wrong end of the telescope. We see things that we think are there, but really aren’t. And the relevant subtleties linger just outside our view, eluding us.

Lawrence Otis Graham ’83 (@lawrenceograham) is an attorney in New York and the author of 14 books, including Our Kind of People and The Senator and The Socialite.

*The name of the boarding school has been fictionalized.

3 Responses

Stephen C. Locher

4 Years AgoLooking Through the Wrong End of the Telescope

Many thanks to PAW for allowing me to read the essay by Lawrence Otis Graham on his family’s experience of oppression by white privileged men and women while they raised their son in a predominantly white community. His essay has in some small way helped me to appreciate the Black experience as seen “through the wrong end of the telescope.” The essay is part of the curriculum for the Unitarian Universalist Wellspring Faithful Action program, through which it will reach a large number of privileged white people working for racial justice in our churches and communities.

Scott Williams ’84

9 Years AgoImproving Race Relations

The following is an expanded version of a letter from PAW’s Nov. 12, 2014, issue.

The Oct. 8 issue is particularly interesting to me as board chair of the Princeton Prize in Race Relations, since it includes several articles relevant to our work. The cover article on race and privilege, the online article about black students in the Ivy League, and the article on Princeton’s repudiation of the Ku Klux Klan (That Was Then) prompt this response.

The Princeton Prize in Race Relations began operating in the fall of 2003. Our mission is “to promote harmony, respect, and understanding among people of different races by identifying and recognizing high-school-age students whose efforts have had a significant, positive effect on race relations in their schools or communities.” For more information, please to go our website: www.princeton.edu/pprize or our YouTube channel: http://www.youtube.com/user/PrincetonPrize/featured.

Our foundational documents state, “Racial conflict is perhaps the most critical domestic issue this country faces. By recognizing, rewarding, and reinforcing the good work of students who are making a difference, the Princeton Prize hopes to promote better race relations now and to provide an impetus for other young people to work toward racial understanding in the future — and an activity truly ‘in the nation’s service and in the service of all nations.’ ”

In our almost 12 years of alumni activity to identify and recognize high school students working to improve race relations, we find that answering the question asked in the From the Editor letter, “How close are we to the dream?,” is complex. While some conflicts are the same, some are retreads of old issues in different forms, and some are completely new. We have observed from the students we honor that steps toward reaching the beloved community of which the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. dreamed can take many forms — from sustained after-school discussions on race, to fashion/culture shows, to poetry slams, to the use of music and art to unite diverse student and community populations. The students who are given Princeton Prize recognition consistently teach us that for good people to do nothing is not an option. Each must do what he or she can when the opportunity arises. Our students have been prompted to act by many circumstances, such as bullying, school Race Awareness Days that were more form than substance, obliviousness to white privilege, race-related violence, ignorance of the background/heritage of ethnic and racial minorities, and sometimes merely a desire to live in a better world.

The Princeton Prize in Race Relations has recognized almost 900 students over the course of its history. We estimate that approximately 200 alumni and community leaders are involved in our 25 regions. Whether or not you as alumni choose to engage with the Princeton Prize and help us in this small way to improve race relations, it is our hope that you will work in the nation’s service to improve race relations in the way that best suits you.

Anonymous

9 Years AgoThe Rules: Readers Respond

Lawrence Otis Graham ’83’s essay in the Oct. 8 issue, describing how affluence and status couldn’t shield his family from bigotry, drew a large response from readers. Here are excerpts from letters, Web comments, and social-media posts; more can be found at PAW Online.

I give thanks that Lawrence Otis Graham ’83 boldly put his personal account into print. On a weekend when my church in Washington, D.C., celebrated 60 years of racial integration, I was profoundly saddened by reading his article. He reminded me of stories told by friends and colleagues — the Afro-Caribbean boxer who, to avoid police detention, “dressed up” to ride his bicycle through an affluent Route 1 suburb to reach the gym where he trained; the colleague who shared how the waitress had filled in the gratuity line on his restaurant bill because “you people don’t tip”; and others.

It should greatly distress those of us who benefit from the privileges and protections of whiteness when legislatures and courts visibly shrink legal protections for the dignity and rights of people of color. But our shame should run deeper when white culture, on the street or in its elites, quietly neglects, prejudges, or condemns a person on the basis of color alone.

Mr. Graham makes clear that the petty grit of white privilege and prejudice tightly clings to the American fabric. He offers us a disturbing but necessary wake-up call.

The Rev. John S. Kidd ’72

Washington, D.C.

I was perplexed by Lawrence Graham’s article about how his affluence and status failed to shield his family from bigotry. The rules his children were taught to follow to reduce the risks of being profiled were heartrending reminders of the continuing barriers they and other minorities face. But why did Graham think his achievements would insulate his son from some louts, presumably resentful of the fancy private school he attends, shouting a racial epithet at him? What did he expect school authorities whose response he found lackadaisical to do? And how was his son so seemingly unaware that, despite the post-racial milieu among his privileged classmates, some racism persists in our society?

Philipp Bleek ’99

Monterey, Calif.

Great piece on how race is still so present in our lives. Thank you for sharing.

Heidi Miller ’74

Greenwich, Conn.

My heart broke many times as I read Lawrence Otis Graham’s article. His recollections and his son’s experiences resonate with me and, I’m sure, with many blacks who believe that education and/or wealth will shield us from certain indignities. The “rules” I learned as a black child newly arrived from London were similar in intent. My parents taught me always to be polite, to never fight back, and to leave any space I used cleaner than I found it — so no one would think blacks were violent or dirty. Outraged, my heart would break as I cleaned up urine or garbage left by people who used public toilets before me. As I now teach my 11-year-old not to wear his black (Princeton) hooded sweatshirt at dusk, and other rules tailored to his current dangers, my heart breaks again. These contortions are necessary to protect ourselves and our children, but they’re also hurtful.

The rules suggest that we control others’ negative perceptions of us. But sometimes, racial hatred is willfully blind to your humanity and dignity, as shown by the men who verbally assaulted Lawrence’s son. So I devised another, color-blind rule that I’ve passed on to my own son: There are damaged people who derive power from others’ pain. Never forget that, but never be like them.

Andrée Peart Laney ’83

Scotch Plains, N.J.

No matter how gut-wrenching and grossly demeaning the indignities Mr. Graham describes and the wisdom to his children to avoid, endure, or tolerate them, they don’t match the racist brutality heaped upon African Americans in the South of my youth. Even so, the civil-rights struggle moved cities and towns like Birmingham and Selma, Ala., Philadelphia and Jackson, Miss., as well as Memphis, Tenn., from murderous racial violence to the election of black mayors — some of them multiple times. As painful as stop-and-frisk, driving-while-black, and excessive surveillance by security guards are — even the shooting of far too many unarmed black males by law-enforcement officers — they don’t rise to the level of the assassination of Medgar Evers, the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, the murder of the three civil-rights workers in Philadelphia, Miss., “Bloody Sunday”and the murder of civil-rights workers in Selma, Ala., and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King in Memphis. If we can’t confront and solve much of what Mr. Graham describes, history will be very unkind to us when it compares our time with the 1950s and 1960s — and rightly so!

David L. Evans *66

Cambridge, Mass.

This is compelling, heartbreaking, and so important for all of us to understand. The fear and institutionalized and personal racism that persist in our society have to be called out and named. Thank you, Larry Graham, for your honest and clear-headed account.

Cathy Ruckelshaus ’83

Chappaqua, N.Y.

Despite the subtitle on the cover of PAW, the point of this article must not simply be the alarming futility of protecting one’s self or family. It needs to be about re-examining the value of being exceptional.

What is it about Ivy-grade intelligence that makes some of us think we can “earn” an “exemption” from exposure to unwanted characteristics of cultures of exception, but still have generous access to the desirables? Cultures of exception actually function on the basis of “needing” the exceptions. That leads to systemic behaviors to assure that (a) the need is met and that (b) the opportunity to meet the need is “protected.” Some of those behaviors are greed, paranoia, aggression, and idiocy.

Facing such behaviors, “smart” people can spot and embrace the formula of cultivating separation as exclusion. Alternatively, being raised in an environment of cultivated separation can easily create a mindset where one thinks, “I don’t know how to be exceptional without being exclusive.” Those birds of a feather flock all the way to exclusionary societies.

Mr. Graham’s story is one about dedicating his adult life to a world of exceptions, by the way, among mostly white rich people instead of mostly black rich people. Graham’s situation started with a stipulation ... that exceptional is good. And we should ask, “For what?” Graham had thought he knew enough about being exceptional, but he now describes that he didn’t. Yet someone with his means should have a better response than “The Rules.”

Malcolm Ryder ’76

Oakland, Calif.

I am most grateful for the article by Lawrence Otis Graham about race and privilege. I have been in discussion with individuals and groups in Baltimore around this issue, and Mr. Graham’s article is one of the most helpful things I have seen.

John B. Powell Jr. ’59

Baltimore, Md.

My late husband and I, ’70s-era prep school/Ivy League/Seven Sisters “Exceptional Negro” alums, home-schooled our three sons with African and African American, mostly male grad students at Ohio State to teach biology, French, and mathematics. We traveled internationally with our sons and sent them to space camp, oceanography camp, engineering camp, etc., with an eye toward developing conscious, global citizens, judged by the content of their character. Hah!

In 1998 our eldest — twins — were barely at Princeton 30 days before “the dark one” was stopped at 10 a.m. and asked by five campus police officers to show proof of ownership of his bicycle. No one in authority thought it significant — until their father arrived. The University’s response? “You are too involved in your son’s life.”

Years later, at the other twin’s philosophy-department graduation reception, neither faculty nor staff spoke to him, us, or his grandparents. My father turned to my husband and said, “Einstein’s theory extends beyond energy. Systems of white supremacy are never destroyed, just reconfigured.’”

I’m sorry your son and your family had to endure this trauma, but as the old folks say in church, “Count it all joy” ... your black son could have been shot or killed. Pace yourself; it’s a very long and arduous journey bringing black American sons to safe adulthood.

Paula Penn-Nabrit p’03

Westerville, Ohio

I really appreciate Lawrence’s article. His son’s story helped me see “white privilege” more clearly. I am white and have always understood it to mean: “Things happen to others that don’t happen to you. You are afforded a privilege of not having certain things happen.” However, it was always very abstract. Maybe the adage of it being difficult to see what you don’t see is apt. But reading the rules he and his wife set for their children helped me to connect with it in a real way. When I imagined myself being given those rules or giving them to my own children, the reality of being my race was more clear. Thank you for helping me to see this.

William Stevenson ’99

Manhasset, N.Y.