Searching for Palestine, and Herself

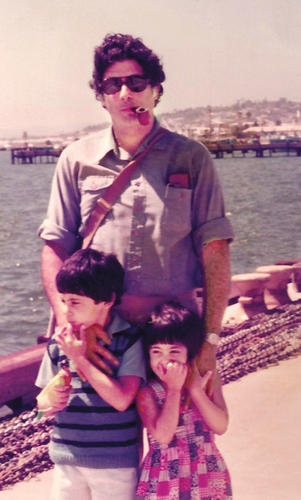

In the shadow of her father, Najla Said ’96 forges her own identity

Najla Said ’96 — a Palestinian-Lebanese American, culturally secular, nominally Christian — has wrestled with issues of identity her entire life. If she is a hyphenated American, an open question, which adjectives to choose? Who is she? Even if she’d prefer to stop turning those issues around in her mind for a while, her profession — acting — won’t let her.

An audition one scorching early afternoon this summer in midtown Manhattan illustrates her awkward spot in America’s race-ethnicity matrix. In a hot studio, she is trying out for the role of a light-skinned black woman who passes as Brazilian in the play By the Way, Meet Vera Stark, set partly in 1930s Hollywood. Her hint-of-olive complexion and dark beauty made the role plausible, but when she emerges from the private audition space into a 12th-floor hallway, pulling back her long hair and wiping sweat from her temple, she comments on the awkwardness of the advice she received at one point in her performance: to bring a “blacker” sensibility to the role. “I feel like a white person acting black,” she complains, good-naturedly but seriously. She didn’t get the part.

The daughter of the late Columbia University literature scholar and Palestinian activist Edward Said ’57, Najla Said often falls between the cracks in this way. When she started out as an actor, she fully expected to be offered “sister of the terrorist” roles, and she has, but it’s been even more complicated than that. She often “reads,” to use the theater jargon, as too white and upper-class for the kinds of working-class street-Arab roles directors have in mind. Then again, if the director wants a mainstream white woman, she can come across as too “ethnic.”

One solution was to write her own path, which she did in the case of Palestine, a one-woman monologue that ran off-Broadway for nine weeks in 2010. It’s a far more personal play than the title suggests, and begins with the striking declaration that, despite her hybrid heritage, she effectively “grew up as a Jew in New York City,” adopting the Upper West Side’s prevailing self-deprecating and cosmopolitan ethos, complete with Yiddish interjections. Until 9/11, at least, anyone who spent 10 minutes with her would have guessed she was Jewish, she says. She now has expanded the material into a book called Looking for Palestine: Growing Up Confused in an Arab-American Family, published in August.

Over the course of the play and book, she confronts anorexia, deals with the long-anticipated death (in 2003) of her father, who was diagnosed with chronic leukemia in 1991, takes shelter from Israeli bombs in Lebanon in 2006, and comes to embrace her Middle Eastern roots. “But none of that has made me less of an Upper West Side princess,” she writes toward the end of the book, with characteristic wryness. Said still performs the play about 10 times a year, usually at colleges and high schools.

She is, and isn’t, a very different person from her father, who still casts an enormous shadow over her life. Edward Said was a learned scholar, born in Jerusalem to Christian parents and raised in Cairo before being sent to prep school in the United States. His book Orientalism, published in 1978, set the agenda for postcolonial studies, documenting how Western scholars had characterized the Near East during the height of Europe’s colonization of the region. In politics, he was a sharp-elbowed pro-Palestinian polemicist who wrote, for example, in November 2001, “most people in the Arab world are convinced — because it is patently true — that America has simply allowed Israel to kill Palestinians at will with U.S. weapons and unconditional political support ... .”

Najla Said is neither a hard-core intellectual nor a political pugilist. “I had the feeling, after my father died, that people were asking me to be him,” she says, sitting in her mother’s spacious apartment in Morningside Heights, with the windows in the curved walls of the living room admitting an expansive view of Riverside Park and the Hudson River beyond. In an adjacent room sit two grand pianos, reminders that classical music was a passion of Edward Said’s.

Even today, people ask her to give lectures about the Palestine-Israel dispute or Middle East politics. “I don’t do his work,” she says, emphatically. “I’m an actress, I’m not an activist. I hate going to protests.” It’s very important, she says, that she not be positioned as an expert — on any subject. “I have a medium, theater, and this is the way that I talk about this stuff. I’m a storyteller.”

Her father wrote in his memoir, Out of Place, that he felt perpetually alienated as a young man, including by Princeton’s “hideous eating-club system.” For all of the humor of Looking for Palestine, Najla Said’s tale has uncanny psychological echoes of Edward’s. But it’s not her similar sense of being an outsider, of belonging-yet-not-belonging, that provides the connection between father and daughter, says Mariam Said, Edward’s widow and Najla’s mother; it’s that “they are extremely sensitive people. That is what she inherited.”

In Looking for Palestine, Said recalls her earliest experiences of Lebanese culture with pleasure, with trips from New York to visit relatives in Beirut equated with “love and grandparents.” But when her parents enrolled her in the tony all-girls Chapin School on the Upper East Side, a sense of difference crept in. She became aware of “my hairy arms, my weird name, my family’s missing presence on the Social Register.”

For a long time, her Lebanese and Palestinian roots, and all that talk about politics at home, served as a barrier to fitting in — her only goal. Around fourth grade, embarrassed, she told a friend’s mother that she’d “forgotten” where her family came from. At 17, during a summer trip to France, she heard people blaming les Arabes for the decline of French life. When she explained that she’s an Arab, they assured her that Lebanese Christians don’t count: They are quasi-Europeans.

After Said’s senior year in high school, she accompanied her father to Jerusalem, to visit the home in which he was born, as well as to the West Bank, Gaza, and Jordan. Her studied political apathy was shaken by Gaza, “where people are trapped like caged animals in the filthiest zoo on Earth, while I somehow got to prance around in suede shoes and $150 skirts and then get on a plane and go home.” (In Jordan, she wiped off a slobbery double-kiss from Yasser Arafat “with disgust” — partly for what she saw as Arafat’s personal ludicrousness. Her father did not entirely disagree with her on this point, she hints, but he described Arafat as “the only leader we have.”)

After Edward’s leukemia diagnosis, Najla, already eating very little, “put starvation into successful practice,” she writes. Her anorexia nearly derailed her start at Princeton, where her brother, Wadie Said ’94, now a law professor, was a student, but she was able to attend while receiving treatment. Courtesy of her father’s cachet, her penchant for urban clothes, and her interest in French literature, she found yet another identity imposed on her at Princeton — that of “European intellectual,” although she secretly wished to “date the cute boys who wore baseball caps who called me dude.”

“Confidence doesn’t come easily to her,” says Michael Wood, a professor emeritus of English and comparative literature, who served as her thesis adviser. He quickly adds: “It’s usually only really smart people who are insecure.” Said’s alienated self-impression was not enough to keep her out of Ivy Club, to her father’s bemusement.

She was in a New York gym when terrorists attacked on Sept. 11, 2001. A trainer turned to her and said the attacks “were clearly the work of the Palestinians.” Said launched into a heated explanation of how the Palestinians had neither the resources nor a motive to attack the United States — but then, her head spinning, she ran outside and called her father for confirmation of her beliefs. (She got voicemail.) Amid the suspicions targeting Arab-Americans in the weeks and months following the attacks, she said she was “crowned and outed as an ‘Arab-American.’” She migrated to an Arab theater collective called Nibras, whose first production, Sajjil (Record), recounted the associations people had to the word “Arab”(“love,” “sand,” “family,” “terrorist,” “angry,” “warm”). It won a prize for best ensemble work at the 2002 New York International Fringe Festival.

Among the hardest parts of watching her father die, she writes, was seeing this most articulate of men lose his grasp of language. Afterward, she had the odd experience of comforting hundreds of people who felt a personal or professional connection to him. “That’s why I insist on calling him ‘Daddy’ in the book,” she says. “There’s this ‘Edward Said’ person and then there’s my Daddy,” she says. “And I want that to be clear, because people still tell me how much they miss him and they ‘ache for him’ — these words. ‘His voice is so needed that sometimes I cry.’ I’m like, ‘You didn’t even know him.’”

Even before her father’s death, Said began to visit Lebanon more often on her own. She recognizes that she can sound “like a rabid Orientalist” in rhapsodizing about the warmth of its culture, in which you’re given a pet name (“Najjoulie,” “Noonie”); instead of “thank you,” people say, “God bless your hands.”

The most politically charged moment in her book and play comes when she finds herself in Beirut in 2006, during the Israeli incursion into Lebanon, listening as bombs come ever closer. It “was the first time I had ever experienced real, pure, true hate,” she writes. But the feeling quickly passed because “(1) I was able to get out; (2) I am lucky enough to know some good people on the ‘other side’; and (3) I was able to talk on the phone daily with my Jewish therapist in New York.”

That last line defused all tension in the theater, says Sturgis Warner, who coached Said during the writing of Palestine and served as director. He adds, “Najla is able to get Palestinian and Arab-American points of view across in ways that can be heard by Zionists, or by people who are very pro-Israel.”

Polemics may not be her style, but it’s impossible for someone with her interests, and last name, not to court controversy. She is insistent on rebutting the notion that the Israeli-Palestinian dispute is “an equal conflict,” as Israel has a strong military, funding, and international backing. Toward the end of his life, Edward Said rejected the two-state solution, preferring a bi-national state of Jews and Palestinians. “What he wanted was for everyone to have equal rights,” says Najla, who herself endorses the one-state idea. “Whatever my dad’s politics were, you can assume they are my own,” she says.

In 2005, in response to Said, Martin S. Kramer ’75 *82, then a professor of Middle Eastern and African Studies at Tel Aviv University and now president of a new college in Jerusalem, wrote that the one-state solution amounted to “a ‘final solution’ for Israel, a denial of the national aspirations and right to self-determination of nearly six million Israeli Jews.” Of her own support for the idea, Najla Said says: “That doesn’t mean I expect to see it in my lifetime. That doesn’t mean that the two-state solution isn’t a necessary step. I don’t pretend to know anything about diplomacy or politics. I don’t know how things go from the micro level to the macro level of changing the world.”

As the conversation becomes more political, Said, sitting in the living room that still contains her father’s favorite reading chair, turns the subject back to her status as an actor and storyteller. “I don’t think I need to scream and yell or throw rocks to tell you that [the occupation] is an unfair, unjust system,” she says. “When I tell people that if we flew to Israel, even with my American passport, and being born and raised here, I would not be let in as easily as they would, or maybe I wouldn’t be let in at all — it does have an effect.” When she speaks onstage or, now, at book readings, about cowering in Beirut as Israeli planes made bombing runs, “That’s more powerful than me talking about the Oslo Accords.”

Christopher Shea ’91 is a contributing writer at The Chronicle of Higher Education.

No responses yet