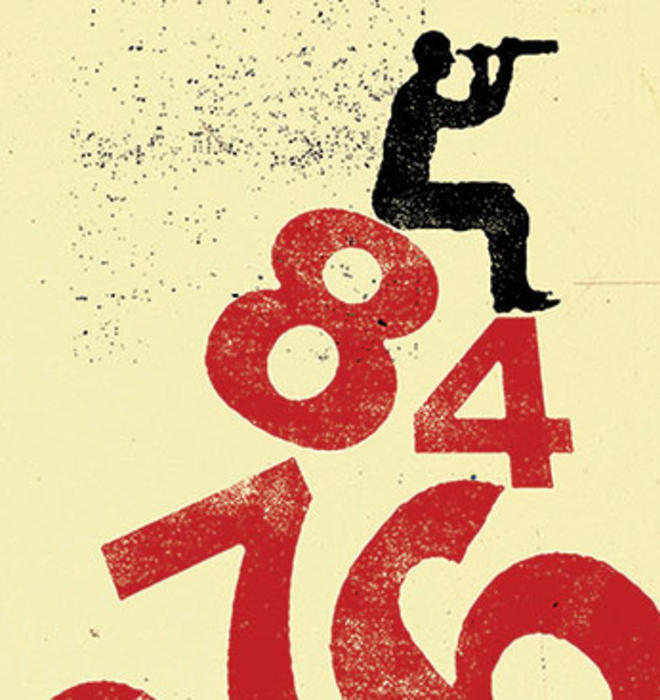

Second Opinion: Another View of Influence

I was surprised how quickly an innocent-seeming meeting, to which I was invited with several other Princeton faculty members and others to select 20–25 “most influential Princetonians,” turned out to be, well, complicated.

As we deliberated, it didn’t take long for unconscious bias to affect the kinds of names that came most immediately to mind. After all, “most influential” seems by default to mean most famous, most visible, most wealthy, most powerful, and, through no malicious intent whatsoever, mostly male and mostly white.

Certainly, a Supreme Court justice is a person of high influence. Princeton is lucky to boast three alums on today’s highest court, people of influence all (and happily, two of them women and one of those a woman of color).

Certainly, a man whose business model revolutionizes the global economy is a person of vast influence. And for good reason, so are all the other people whom we decided to list.

But do we only value fame, visibility, and radical effects on global social, political, and financial systems as influential? What do we leave out when we neglect to value the more quotidian interactions propagated by, for instance, kindergarten teachers, who show 5-year-olds how to tie their shoes and how to share their books and toys and be kind to one another?

I recently also participated in a focus-group conversation among female faculty and staff in preparation for the second “She Roars” conference, an event that celebrates Princeton alumnae. Those at my lunch table discussed the anxiety of Reunions for alumnae who come back to campus without the glossy patina of public or corporate influence or elite literary status. (In fact, one of the most influential Princetonians on our current list, Jennifer Weiner, published a New York Times op-ed piece about just this issue: “The Snobs and Me,” June 10, 2016.)

What of the stay-at-home parent, whose most effective work might be raising his or her children or volunteering at a community center or house of worship? What of people who decline to enter the battle of contemporary discourse but serve in local businesses or community settings as thought leaders? What of the women who brave the internet’s mudslinging to add their voices to #MeToo, whose names might encourage their colleagues or neighbors to share their own stories of harassment or assault? Are they not influential?

In 2011, then-President Shirley Tilghman used the Steering Committee on Undergraduate Women’s Leadership report to raise consciousness about the relative paucity of women in campus leadership positions. But even then, task-force participants and report respondents suggested that many women lead differently, in less visible or vocal positions.

At our “She Roars” luncheon, for example, a Lewis Center colleague pointed out that many white male artistic directors — the most influential people at American regional theaters — are supported and guided by invisible backup groups of often ethnically and racially diverse women. How do we acknowledge influence that’s suppressed by the power that circulates in many professional and creative settings? And how do we, as Tilghman did with the women’s leadership report, encourage women to step out and up into more visible, commanding, and forceful positions?

My concerns about the bias of influence were underlined when I read the Oct. 4 PAW story about Nikki Bowen ’08. Hired fresh out of Princeton at a charter school in New York through Teach for America, Bowen was unsure she’d return to the school after an arduous year of teaching. Then she encountered the mother of a student, who told her, “What you teachers don’t get is that our kids — you have a huge impact on their lives. They love you all. They look up to you.” Bowen stayed in teaching, and is now the principal of the Excellence Girls and Excellence Boys charter schools in Brooklyn.

Although it might seem a more mundane gesture, I encourage Princeton students to see their contributions to classroom discussions as influential. Likewise, when I see them perform onstage; when I watch them play on our sports teams; when I see them present their work on Princeton Research Day; when I hear them protest national or local policies ... each of these contributions and interactions is meaningful to our campus, regardless of how routine or fleeting it might seem.

If “most” influential, however, means Princetonians whose lives and careers have affected vast numbers of people, I understand why our list appears as it does. But we’ll never get past that unconscious bias of whiteness and maleness if we don’t make our definition more elastic. A Princeton degree is a tool; its real value comes from how alumni put it to work. Whether their work is paid or volunteer, local or global, domestic or public, quotidian or extraordinary, our alumni should aspire to use their education to affect as many people as possible. We need their influence now, more than ever.

No responses yet