The senator’s next act

Former Majority Leader Bill Frist ’74 and Professor Uwe Reinhardt offer different takes on health policy in their class

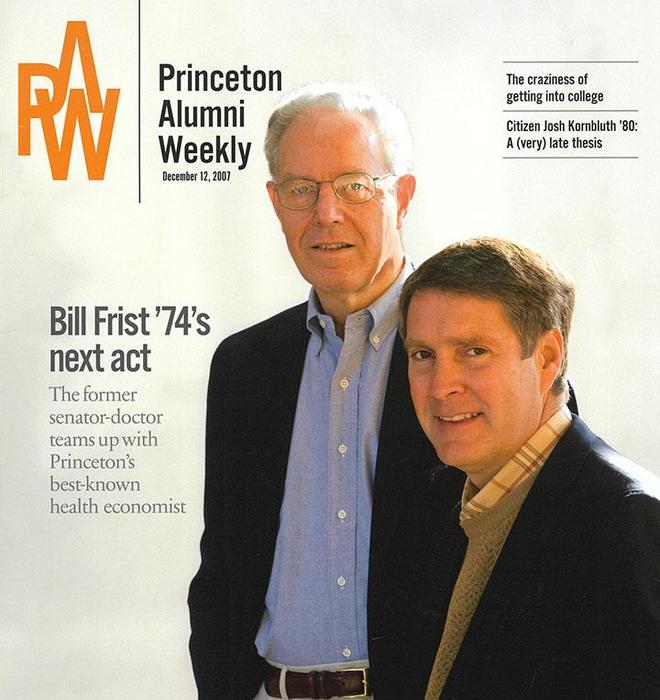

By some lights, Uwe Reinhardt, a professor of economics and public affairs and a specialist in health policy, and Bill Frist ’74, the heart-surgeon-turned-Senate-majority-leader who recently stepped down from public office — and whose surname adorns the Princeton campus center — make for an odd couple.

The dryly witty Reinhardt claims to aspire to scrupulous neutrality in the classroom — “the ideal college professor is very skillfully lobotomized,” he says — but as an émigré from Germany by way of Canada, he clearly finds the American tolerance for inequality in health care distasteful. “In Canada and Germany, the idea that somebody who is sick would also go broke would be extremely repugnant,” he says, “while in the U.S. it is extremely acceptable.”

Frist, meanwhile, presided over the Senate at a time when his party controlled both the executive and legislative branches, a period when the ranks of uninsured Americans grew by about a million people a year, to 47 million today. “We made no real dent” in the problem, he concedes.

More evidence of an apparent intellectual incompatibility between Reinhardt and Frist: Every four years Reinhardt writes a widely circulated primer for journalists on health-care issues that begins by declaring his “bias” in favor of universal health insurance but then describes the competing plans in fairly straightforward terms. His version for 2004 basically said that President Bush simply was not serious about the problem of Americans without health insurance — first, because the president devoted only $10 billion or so annually to the cause (Reinhardt said a serious effort then would have cost $100 billion), and, second, because Bush’s main proposal, tax credits only large enough to allow the purchase of “catastrophic” insurance plans, would discourage routine health care. It would force middle- and low-income Americans, and only those groups, to self-ration, he said. Reinhardt also nitpicked the plan of the Democratic presidential candidate, Sen. John Kerry, but pointed out that it would have reduced the ranks of the uninsured by 25 million, while being far from “socialized medicine.”

At around the same time, Frist was slamming Kerry’s health-reform plan as, yes, socialized medicine. His own specialty of heart-and-lung transplant surgery would “be essentially taken over by the government,” Frist said.

Despite the gap between their worldviews, Reinhardt and Frist — the social democrat and the self-declared Reagan Republican — teamed up this semester to teach a graduate course, “The Political Economy of Health Systems,” at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. It’s part of Frist’s yearlong stint as a visiting professor; officially, he’s the Frederick H. Schultz Class of 1951 Visiting Professor of International Economic Policy. It’s a counter-intuitive pairing, but not a chance one: Almost 35 years ago, as a student, Frist took Reinhardt’s courses on microeconomics, accounting, and corporate finance. In the words of his teacher, “He was tops in every one of those classes.” A Wilson School major, Frist wrote his thesis under the late Herman Somers, one of the godfathers of managed care.

Reinhardt and Frist stayed in touch as Frist departed for Harvard Medical School and, from there, to a surgical residency at Stanford and a career, in Nashville, as one of the nation’s top heart-transplant surgeons. Throughout Frist’s medical career, and on through his political one, Frist and Reinhardt have stayed close and kept up a running conversation on health care. In the early 1990s, Reinhardt was Frist’s guest in Nashville as Frist performed a late-night heart transplant. On a more personal note, in 2004, Frist hand-delivered a set of binoculars to Reinhardt’s son, Mark Reinhardt ’01, who was then serving as a Marine Corps lieutenant in Ramadi, Iraq. (To be precise, Frist hand-delivered them to a Marine general, who then had to schlepp the box around for weeks. When he found Mark, he gave him serious grief for his lofty connections, barking, “Who do you know?”)

From the moment Frist announced his entry into politics, his friends and supporters say, he had his eye on the presidency. But though he tested the waters, it was not to be. Now Frist is using Princeton as a launching pad for what he describes as the third stage of a career he says is focused on one theme: healing. “For me, politics has always been just a means to an end,” he says during a walk through Wallace Hall to his spare office. Hands-on healing, he says, led to recognition of the limits of what one doctor can do and to an interest in politics. For his third act, he hopes to shape the national conversation about both international aid and domestic health care.

So far, much of his work has been on the international front. In September, the charity Save the Children announced that Frist would head its Survive to 5 campaign, which aims to persuade the United States to increase from $350 million to $1.6 billion annually what it spends to combat treatable maladies such as diarrhea, pneumonia, and birth complications, which kill some 10 million children worldwide each year. Frist sealed the Survive to 5 affiliation in August by traveling to Bangladesh, in monsoon season, visiting vaccination outposts and listening as health providers coached pregnant women on the warning signs of problems during delivery, which rarely takes place with a doctor present.

With Tom Daschle, the former Democratic senator from Iowa, Frist is co-chairman of the One Vote ’08 campaign, affiliated with Bono, of the band U2. Its goal is to make global health and extreme poverty a priority issue in the 2008 presidential campaign.

“I’m here really looking at the next 10 years,” Frist says. “That’s why I want the total immersion in the research end of it, the teaching, and the studying end. I’m around good people here. There are good economists here, and good environmental people.” In combating global diseases, he points out, knowledge of local ecosystems becomes ever more important. “It’s a very rich, robust environment for what I want.”

Though Frist stresses the continuity of his endeavors, there’s also some evidence that he wants to reinvent himself, to erase some of the shaky public relations of his last years in political office and throw off the constraints of electoral calculation. He cites Al Gore as an inspiration — the Gore who remains a risible figure to many Republicans, the Gore who came back from a presidential campaign in which he was accused of being overly cautious to become a fierce voice in favor of steps to stop global warming, and against the Iraq war. “Gore followed his passion, which was the environment,” Frist says in his office. “And outside the political system he built the case — using science, policy, the media — to educate the nation about something it didn’t know.” He doesn’t fail to note that Gore may have done a better job once “freed” of his political responsibilities.

To be fair, during his Senate career, Frist did sponsor or support health-care programs that made small, reform-minded steps: The Health Insurance Portability Act of 1996, which ensured that people who lose their jobs can still get insurance of some sort; the State Children’s Health Insurance Program, in 1997, which expanded coverage for low-income children; and the creation of tax-free Health Savings Accounts in 2003. Still, whether because of the lack of consensus in America on how to remedy the problem

of the uninsured (the view of Frist’s supporters) or because of his Republican peers’ lack of interest in the subject (the view of many Democrats), that problem only worsened on his watch. “I wouldn’t put the failure mostly on him, or only on him — but it has been a failure across the board, for the president, and the congressional leadership, and the Congress,” says Jonathan Oberlander, an associate professor in the School of Public Health at the University of North Carolina. “I think history probably won’t treat this period very kindly.”

Frist is adamant, however, that much was accomplished on health care during the time he led the Senate, and that Republicans frequently were more creative and daring on health issues than Democrats. Drawing on the humanitarian work he did each year in Africa, often in connection with Samaritan’s Purse, a nonprofit group run by Franklin Graham, son of the evangelist Billy Graham, Frist made the case to President Bush for AIDS relief. “We committed $15 billion over three years, which is the largest single initiative on global health on a single disease ever in the history of mankind,” Frist says. On this issue, James Sykes, global program coordinator of the AIDS Institute, in Washington, D.C., says of Frist: “You have to give him his props.”

On the domestic front, Frist points to the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, which brought a prescription-drug benefit to the 43 million participants in the Medicare program for the first time. “It’s a beautiful piece of legislation,” Frist says. To be sure, that program remains controversial. Paul Starr, a Princeton sociologist and Wilson School professor, co-editor of the liberal American Prospect magazine, and author of the Pulitzer-winning book The Social Transformation of American Medicine, says the bill was “weighted down with favors for the pharmaceutical industry and much more expensive than it otherwise could have been.” On the other end of the political spectrum, Michael Cannon, director of health-policy studies at the libertarian Cato Institute, calls it “the largest expansion of the welfare state since Lyndon Johnson.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, Frist’s Princeton appointment raised a few eyebrows, not because of his legislative initiatives — or lack thereof — but because of several incidents that drew a great deal of public attention: specifically, instances in which he was accused of pandering to the religious right on medical questions and abandoning a doctor’s commitment to evidence over ideology. Frist leaned on his reputation as a world-class surgeon, for instance, when he argued that Congress should intervene to save the life of Terri Schiavo, the brain-damaged Florida woman who courts had ruled could be taken off life support at the request of her husband, her medical guardian. Her biological family fought the decision, and the case became a cause célèbre among Christian conservatives.

On the Senate floor, in March 2005, Frist suggested that court-appointed neurologists likely were wrong in judging that she was in a persistent vegetative state. “Based on the [video] footage provided to me, which was part of the facts of the case, Schiavo does respond” to other people, he said. In another much-discussed incident, on ABC News’This Week, host George Stephanopoulos pressed Frist to disavow dubious claims being made in some government-funded abstinence-only sexual-education courses. Did Frist, Stephanopoulos asked, believe sweat and tears could spread AIDS? “I don’t know,” he replied, adding a bit later: “It would be very hard.” (The Centers for Disease Control says that there has never been a case of transmission through sweat or tears.) On that same show, Frist said condoms fail 15 percent of the time; the CDC puts the figure at 2 percent. After the Schiavo and ABC incidents, the liberal New York Times columnist Frank Rich called Frist “the most craven politician in Washington.”

Frist defends his conduct in both cases. “From a moral standpoint,” he says, “it is hard to argue that the government should cause someone’s death who is not on a ventilator, not on life support, does not meet the scientific criteria for brain death, when all blood relatives say: ‘Do not allow her to die.’ Politically it probably is not wise to get involved in that sort of thing, but from a moral standpoint, it is.” As for AIDS and sweat, he scoffs at the idea, given his background, that he does not know the basic facts about the disease. AIDS theoretically can be spread via any bodily secretion, he maintains. “It can — all that prefaced with the fact that it is one of the least infective, least communicable viruses around.”

Because of such episodes, “I think [Reinhardt] should find it difficult to have Bill Frist in class with him,” says Ted Marmor, an emeritus public-policy professor and political scientist at Yale who specializes in health-care policy. “Bill Frist behaved terribly when he was interested in the presidency.” Such issues did come up among the Wilson School faculty, which had to approve Frist’s appointment, Paul Starr says. “There was some discussion, there was some controversy — I can’t say it was all that prolonged — and then the vote. And the vote was overwhelmingly in favor of his appointment.” Yet Starr also makes clear: “I’m perfectly happy that he’s here. I’m delighted to have the discussions and the debate that we ought to have, and that students ought to take part in.”

Reinhardt, for his part, downplays the ideological differences between him and Frist. “Except for health care, I was always considered more centrist or to the right,” he says. “When I first came to Princeton, I was often brought out to talk to corporate executives, because I respect them and get along with them.” On health care, the tenor of conversation between professor and former student “tends to be more technical” than ideological, he says.

“When you are with him, he does not ooze ideology,” says Reinhardt.

In the aftermath of the Newt Gingrich-led Republican Revolution of the mid-1990s, Frist was “one of the most reasonable guys” on the GOP side of the aisle, Reinhardt avers. When Frist was still unpacking his boxes in his Senate office, Reinhardt and some of his health-care colleagues appealed to him to save a small federal agency, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, that was targeted for elimination by the Republicans. Frist did — part of his rescue effort involved rechristening it as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, a more conservative-friendly name.

Whatever ideological differences exist between Frist and Reinhardt are largely submerged in the course they co-teach. As teachers, their styles are quite different: Reinhardt is the polished, broad-view lecturer and sometime stand-up comic; Frist works harder at engaging students in conversation and immerses himself in policy detail.

On one Monday-morning session early in the semester, Reinhardt took the lead, with Frist sitting off to the side in suit and tie, prepared to head after class to the Clinton Global Initiative meetings in New York. Reinhardt spent much of the time wryly deconstructing economic rhetoric about “efficiency” in health care. Health insurance is “inefficient” by its very nature, he pointed out: It encourages people to buy more health care than they might otherwise. Too often, Reinhardt continued, politicians defer to professional economic–speak about efficiency. In doing so, they fail to realize that economists are masking their own moral preferences — often, a sort of Darwinian amorality — in the language of social science.

“When you say the Canadian system is more inefficient than ours, I say you can’t make such comparisons,” Reinhardt said. “These countries have different goals. The Canadians are rabid about egalitarianism.” In other words, if egalitarianism is your goal, an inefficient route in that direction makes more sense than a swift, efficient path to inequality.

If Frist balked at Reinhardt’s defense of the Canadian system, he didn’t show it. He spoke up only occasionally, usually offering an insight from his own time as a doctor. One student, for example, floated the idea that health costs for the elderly would go down as more and more of them became health-conscious. “The cost burden isn’t less,” Frist said. “I now have people in their 70s asking for heart transplants” — whereas once they would have been deemed too elderly for such a radical intervention.

Both Frist and Reinhardt agree that low-income Americans are sailing toward fiscal disaster where health insurance is concerned. If wages and health insurance continue to grow at current rates, someone making $40,000 in wages and benefits a decade from now will have to devote half or more of that figure to health insurance, Reinhardt notes.

Unsurprisingly, Reinhardt has the more specific plan to remedy the problem and cover the uninsured. For individualist America, he eschews a single-payer system. “You can’t grow oranges at the North Pole,” he says, a metaphor for cultural differences. He would mandate coverage for young, healthy people and raise federal taxes to pay for the premiums of the poor and near-poor (rebranding these taxes Membership Fees for the Club of Civilized Nations). The poor and near-poor could use vouchers to buy into Medicare or private plans; to spread risk, the government would partly subsidize those plans that attracted an unusual number of ill citizens. Competition among plans would help to reduce cost increases: It’s a version of the managed competition that scholars have been tinkering with for 30 years.

Frist places more hope in information technology, which he believes will give consumers the tools to compare practitioners and costs of procedures. “That is where Uwe and I probably part,” Frist says. “I believe that consumers, smart shoppers out there, can affect the system.” Reinhardt thinks health care is intrinsically too complex and inscrutable for consumers to be able to choose sensibly. “It’s like pushing someone into Macy’s blindfolded and saying, ‘Find a shirt you like at a good price,’” he says, adding that the two have sparred over the issue in class.

On another Monday morning, with Reinhardt absent, Frist took over and the class became a policy wonkfest. The subject was TennCare, an attempt by Frist’s home state to tackle the problem of the uninsured and a ballooning Medicaid budget. In 1994, Tennessee created a system of a dozen or so managed-care organizations to serve the 800,000 people on Medicaid and the 500,000 who were uninsured. The theory was that the managed-care groups would compete among themselves and thereby wring inefficiency out of the system.

But Tennessee required that the organizations pay for all “medically necessary” procedures and demanded few or no co-payments from plan members. There was effectively no cost control. By 2005, Frist explained, TennCare was in hopeless shape, and Gov. Phil Bredesen pulled the plug. The lesson? “You have to have more than an egalitarian goal,” Frist told the class.

“One thing Frist does is he really takes the real-world examples seriously — stressing how certain things aren’t so easy,” says Toni De Mello, a second-year master’s-degree student from Toronto, who has worked for the U.N. on refugee relief in Senegal. “So Reinhardt will say the pharmaceutical industry is making too much money — their profits are astronomical. Frist will say that even if they make so many millions of dollars on a single drug, they have to test 99 before discovering the one that works.” De Mello disagrees with Frist’s politics, but says “he has opened my eyes to a lot of the constraints he faced as a politician.”

De Mello is one of several students to say Frist has thrown himself with surprising passion into teaching, given his stature. “On the first day of class, he said, ‘I want to know why you are here, what your backgrounds are,’ and he took notes” — and he draws on those notes, calling on people when their experiences are relevant, she says.

Frist also is supervising independent research. David Kuwayama, a second-year M.P.A. student in Frist’s class, is a Harvard-trained surgeon who took time off from his residency at Johns Hopkins to practice in Haiti, working with Partners in Health, a charity founded by the famed humanitarian physician Paul Farmer. Humanitarian doctors are common, “but for some reason surgeons have not taken the lead in this kind of work,” Kuwayama observes. Under Frist, Kuwayama will attempt a clinical evaluation of the surgical needs of residents in a refugee camp near a conflict zone, probably in Chad. Frist, with his highly publicized trips to Africa, is one of the high-profile exceptions to the rule that surgeons don’t get involved in humanitarian work — making him a perfect mentor, Kuwayama says.

Indeed, the drive that Frist displayed as a student, doctor, and senator — he would swing by the National Zoo before dawn on his way to Capitol Hill to do cardiac evaluations on gorillas — has carried over into his third career. Over the course of a single week, early in the semester, he jetted off to give a keynote address at the Aspen Health Summit in Colorado, then returned to teach, then gave a presentation to the Princeton Bioethics Forum. (He discussed the case of a Tennessee woman who recently had been turned down for a kidney transplant because of a history of alcoholism; he had directed her to a center with a more lenient policy.) He dined with Whig-Clio members at a local restaurant, met with members of Princeton-in-Africa, and discussed his own career at Cottage Club. He was especially proud of a speakerphone chat with a high school class in Missouri.

For students and alumni turned off by Frist’s politics, or by Bush’s for that matter, Reinhardt has some advice. He made the comment abstractly, during a discussion in his office of Bush’s veto of a bill that would have expanded S-CHIP, the program that subsidizes health insurance for low-income children.

“When it comes to the other side, you shouldn’t call them names,” Reinhardt says. “Even if you think it is a good thing to cover all children, part of the art of policy-making is to respect the other side, and work with them.”

You could say that’s what both Frist and Reinhardt are doing now, twice a week, in that Woodrow Wilson School basement seminar room.

No responses yet