Shirt cuffs and other artifacts of student life

A special exhibition offers unexpected views of Princeton’s history

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Princeton University Archives.

From their beginnings on a few shelves of the Rare Books and Manuscripts department in Firestone Library, the archives have grown to take up more than half of the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, with papers, photographs, films, and artifacts occupying more than three miles of shelf space. It is the best collection of Princetoniana in the world and an invaluable source of information about the University and the history of American higher education in general. Each year, more than 1,200 people visit the archives to do research, while 1,500 more submit queries by phone, fax, or e-mail.

Through Jan. 29, 2010, Mudd Library is presenting an exhibition — “‘The Best Old Place of All’: Treasures From the Princeton University Archives” — with items ranging from the historically essential to the whimsically idiosyncratic.

The University archives, which occupy the second floor and some of the basement of Mudd (the rest of the building houses the public-policy archives) contain everything from the original University charter issued by King George II to minutes of trustees’ meetings to tens of thousands of photographs.

Like many things at Princeton, the University archives owe much to Moses Taylor Pyne 1877, a longtime trustee and benefactor. Shortly after he was elected trustee at the age of 28, Pyne began collecting and organizing information about Princeton and its alumni, work that led to the establishment of, among other things, the first Annual Giving campaign, the first alumni directory, the Alumni Council, and PAW. Pyne and fellow trustee Bayard Henry 1876 also began gathering materials relating to the founding of the University and its early years.

In addition to papers and documents, the archives contain a fascinating array of artifacts — canes, hatbands, cigarette packs, raw tobacco, dinks (the beanies freshmen once wore), and class beer cans from Reunions gone by — that were donated by alumni. One box contains the cigarette case used by sports icon Hobey Baker ’14. University archivist Daniel Linke says he cannot accept items of clothing, which are rarely of interest to scholars, take up a lot of space, and require special care and handling. An exception to this rule is the rather capacious reunion jacket of Adlai Stevenson ’22, which was included in a bequest of Stevenson’s papers.

Other items, such as old scrapbooks and dance cards from the 19th and early 20th centuries, offer glimpses into students’ lives and interests in a way that more traditional documents do not. Perhaps the most pressing issue facing the archives today is how to preserve a record of contemporary student life — the student e-mails, digital photos, and online social networks that have replaced the letters and scrapbooks of previous generations.

There are some holes in the collection of Princeton history, most not of the library’s doing. Very few of the papers of John Grier Hibben 1882, president from 1912 through 1932, survive, because Hibben burned them. Two Nassau Hall fires, in 1802 and 1855, also destroyed some records, as did a 1945 fire in the gymnasium. To protect against such a calamity happening again, the Mudd archives are protected by a halon fire-suppression system.

Slowly, parts of the collection are being digitized, and many finding aids now can be combed on the Internet. Later this academic year, Linke hopes to host a film festival, featuring snippets of film clips dating back to Hibben’s inauguration. Other items in the audiovisual collection of more than 1,200 items include football films from as far back as the 1920s and a promotional film about Princeton made for the University’s bicentennial in 1946.

The archives tell the story of Princeton with an immediacy that is hard to find in any book. Following is a sampling from the exhibition.

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

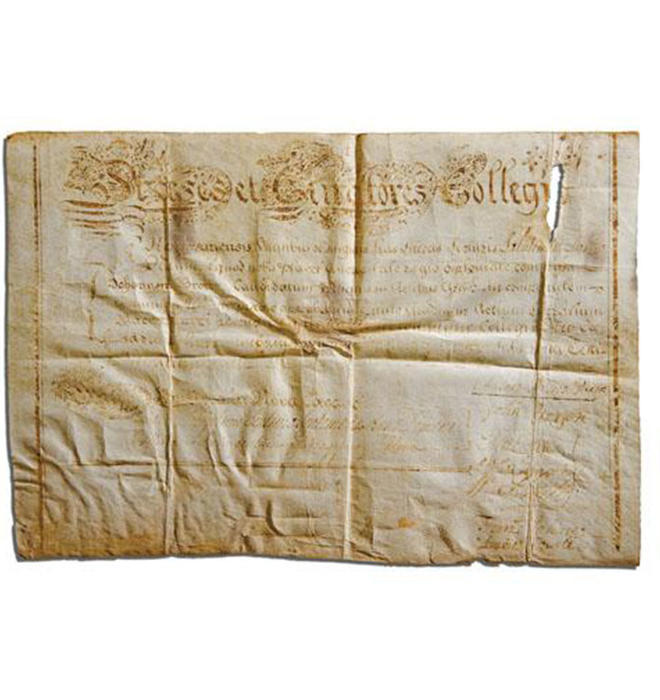

The earliest known surviving diploma, 1749

This diploma, handwritten on parchment, was issued by the College of New Jersey (or Collegii Neo-Caesariensis, as it is inscribed here) to John Brown in 1749. Brown, who was born in Ireland and raised in western Virginia, was one of just seven members of the second graduating class, when the college was located in Newark, N.J. After graduation, he became a Presbyterian minister and for a time supervised the institution that eventually became Washington and Lee University.

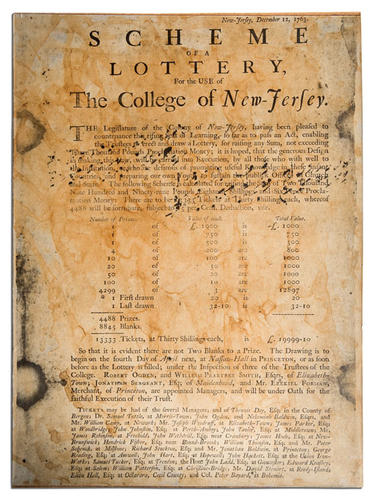

A lottery for Princeton, 1763

With no endowment and limited funds, the College of New Jersey, like many colonial colleges, turned to a lottery to raise money. The top prize of 1,000 pounds and several smaller prizes were awarded in a drawing held at Nassau Hall. Lotteries such as this required authorization by the Legislature. An earlier lottery, proposed in 1748 by David Cowell, a University trustee, did not receive state approval and had to be managed from Connecticut. The 1763 lottery was a success (although officially referring to it as a “scheme” may not sound like the smartest idea to modern ears), but subsequent ones were not. A lottery run from 1772 to 1774 ran into trouble when organizers could not keep track of all the money received, and the idea never was tried again.

Why there is an honor code, 1870

For much of the University’s first two centuries, undergraduate life was anything but intellectual. Cheating and misbehavior were routine in an atmosphere that pitted students and faculty as antagonists. Examples of this anything-goes ethos are these celluloid shirt cuffs belonging to Henry Thompson Cook 1871. Cook carefully wrote on these cuffs the answers to 47 questions on a logic examination that he took at the end of his junior year. It is not known if Cook’s cheating was uncovered, but he did not graduate. Still, it seems unlikely that he was remorseful: The University has these cuffs because Cook saved them and mounted them in a scrapbook with a description of what he had done. Tricks such as this led to the creation of the honor code in 1893.

Student pipes, 1890s

These clay pipes, known as churchwardens, belonged to members of the classes of 1891 and 1897. The custom of smoking such pipes had long gone out of fashion by the late 19th century, but The New York Times described the Princeton tradition in an account of Class Day exercises in 1891. After class president Edgar Allen Poe addressed the class, the Times wrote, “It was at this stage of the programme that an old and interesting custom was introduced. Long clay pipes, tobacco, and matches were passed to each member of the class, and they smoked the ‘pipe of peace’ together. Men who had never used tobacco in any way before smoked with their classmates now.” At the conclusion of this ceremony, the seniors dashed their pipes against the cannon on Cannon Green, bidding symbolic farewell to their undergraduate days. The tradition was discontinued in the 1990s, though the Class of ’59 smashed pipes at Reunions this year.

Blackballed, late 19th century

Bicker has been one of the most controversial social customs at Princeton since the practice began in the 19th century. This box, which once belonged to an eating club, enabled members to vote in secrecy on whether students could join. Those voting in favor of a candidate dropped a white ball into the box, unseen by other members; those opposed dropped a black ball. The term “blackballing” derives from this practice. At some clubs, a single black ball could doom one’s chances of admission.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s grade card, 1917

F. Scott Fitzgerald ’17 had a legendary undergraduate career at Princeton — outside the classroom. Inside, to put it charitably, he was an indifferent student. Grading then was on a scale of 1 (the highest) to 7, so Fitzgerald’s grades — note the 5’s in Latin, physics, and French — would have been just barely passing. His best grades — a pair of 2’s during a second attempt at his junior year — were in literature courses. For most of his time at Princeton, Fitzgerald languished in the lowest quintile of his class. He withdrew midway through his junior year because of bad grades, returned the following fall, but left again to join the Army and never returned as a student. Fitzgerald never graduated, but he did remain close to Princeton for the rest of his life. His first successful novel, This Side of Paradise, remains perhaps the ultimate romantic paean to the University and to an age.

No responses yet