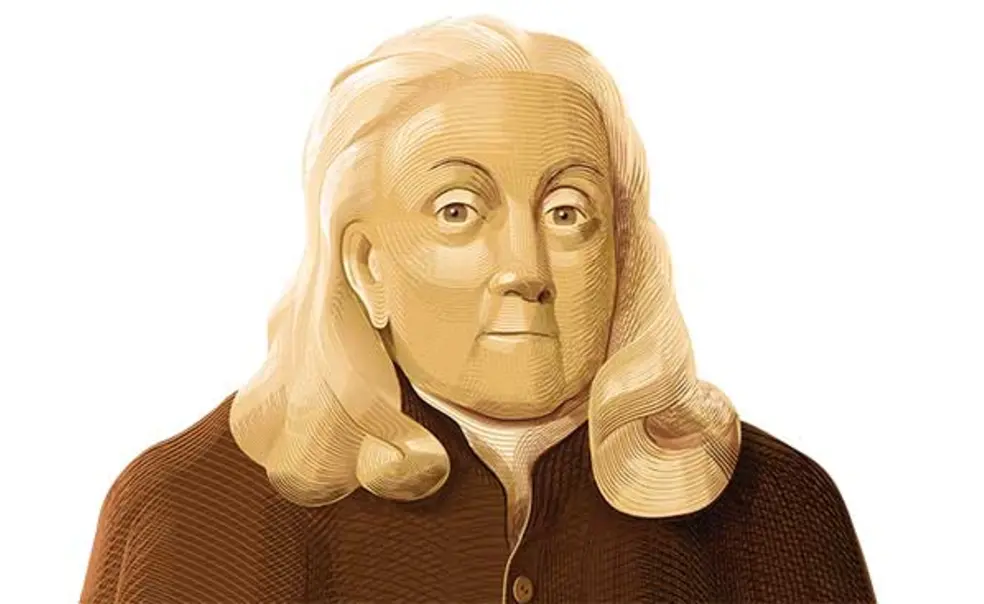

Tapping Reeve 1763 was in love with a clever, wealthy girl, and he hardly had a penny. He had paid his way through the College of New Jersey by teaching at a nearby grammar school and working as a private tutor. Six years later, he began courting one of his former students: Sally Burr, the daughter of the late Aaron Burr Sr., president of the College. Reeve’s gifts lay in teaching, but teaching was not prestigious or remunerative enough to win her guardians’ consent for marriage.

“My dear Sally,” he wrote to her in 1769, “I have just been conversing with your Uncle who says he is resolved to oppose me & treats me hardly with common kindness ... . Oh, my dearest, when they are about to use their arguments with you, judge how meaningful my situation must be when my very happiness itself is at stake ... but rest assured, my faithful Charmer, I will never believe that you will abandon me or prove inconstant.” Aaron Burr Jr. 1772 carried letters between Reeve and his sister.

Reeve took a position as a legal apprentice — most lawyers in the Colonies learned their craft this way. He emerged from his apprenticeship even poorer, but with the prestigious title of lawyer. He married Sally Burr in 1772.

The most obvious way to recover his funds was to take on apprentices in turn. His first arrived in 1774: Sally’s brother, Aaron, who went on to a notable political career. Apprentices kept coming, in numbers that grew and grew. So it was that Reeve, a reluctant lawyer but a passionate teacher, became the founder of the nation’s first law school.

Litchfield Law School opened in Litchfield, Conn., in 1784. Students crowded its single classroom: more than 1,200 over the next 50 years, among them Horace Mann, Samuel Morse, and Noah Webster.

Like most lawyers, Reeve drew on William Blackstone’s works on English common law, but he suggested that some doctrines of the common law were foolish and archaic, as Paul Hicks ’58 notes in a new book about the school. Blackstone claimed that “the husband and wife are one person in law; that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage,” for example. But Reeve argued that when we see a married woman in reality, “we find her often an active agent, executing powers, conveying land, suing with her husband, and liable to be sued with him, and liable to punishment for crimes.” He also told his students that slavery was illegal, being “founded in violence and contrary to the laws of natural justice,” as their notes record. After these lectures, Litchfield’s other teacher would tell the students that, although he too was an abolitionist, he was obliged to affirm that slavery was legal in Connecticut.

Reeve hated Thomas Jefferson. After Jefferson assumed the presidency, Reeve wrote in a newspaper, The Litchfield Monitor, that Jefferson was trying to overthrow the Constitution and set himself up as a tyrant. A grand jury indicted Reeve and the newspaper’s publisher on charges of seditious libel, though the case was eventually dismissed. Reeve did not apologize.

When Harvard opened a law school in 1817, then Yale in 1824, students flocked to the new schools with old names, and Litchfield’s enrollments began to decline. Reeve retired in 1820, and Litchfield Law School closed its doors in 1833.

Tapping Reeve and Sally Burr Reeve had, by all accounts, a very contented marriage. After they wed, he wrote to her, “I am this moment enjoying the incomparable pleasure of reflecting that I have one friend in you that will be ever an unshaken friend and that I can enjoy no prosperity but what must give you satisfaction and make you the happiest.”

He added, “And do not abuse my sweet lips with your savage little teeth.”

2 Responses

Kelley Borden Gray

3 Years AgoFascinating Relative

I recently asked my cousin why her middle name is Reeve. She reminded me that our grandmother’s maiden name was Reeve and that we are related to Tapping Reeve. The article was both educational and enlightening from a genealogical standpoint.

Paul Hicks ’58

5 Years AgoReeve’s Legacy

Tapping Reeve 1763 deserved a much more thoughtful “Princeton Portrait” than the one included in the March 4 issue of PAW. The Litchfield Law School, which was founded by Reeve in 1784, operated for nearly 50 years and educated upward of 1,200 students. It is the subject of my recent book, The Litchfield Law School: Guiding the New Nation.

Its alumni included not only Aaron Burr Jr. 1772 but at least 50 other Princeton graduates. Among these was Henry W. Green 1820, who served as chancellor of New Jersey. Princeton’s first library was named for him.

Instead of dwelling on the love letters that Reeve sent to his fiancée (and later wife) Sally Burr, sister of Aaron Jr., the article should have noted the importance of Reeve and the law school in the development of American legal education. A recent history of the Harvard Law School acknowledged, “In retrospect, both Harvard and Yale have envied Litchfield’s success and wished to claim it as their ancestor.”