The bitter dissension of Woodrow Wilson’s late college presidency appeared forgotten during Reunions in June 1914 when Wilson, a member of the Class of 1879, alighted the Dinky for his class’s 35th reunion. Three members of ’14 and two alumni had won five Rhodes Scholarships, more than the rest of today’s Ivy League put together. Ralph Adams Cram’s Graduate College, the apogee of American collegiate gothic, had been completed the year before, and the University soon would break ground on Palmer Stadium, uniting tradition with the technology of reinforced concrete.

But neither Wilson nor the students could foresee the changes in Princeton (and society) that would follow an assassination in the Balkans later that month. As the Class Day orator that year put it in the class’s 25th-reunion book, 1914 was “the first to step out from Princeton into an exploding world. ... Before some of us had unpacked at home the mementos of our days at Princeton, armies had mobilized in joined battle. The world has been teetering off balance ever since.”

Looking back, some writers have lamented losing the balance of that age. In his 2001 Atlantic essay, “The Organization Kid,” writer David Brooks mourned the character-building spirit of John Grier Hibben 1882’s presidency, which followed Wilson’s — the sense that “life is a noble mission and a perpetual war against sin” — and noted the downsides of today’s meritocracy. But the high moral tone depended on an identity as gentlemen, a word that retained something of its original meaning of good family as well as politeness.

As W. Bruce Leslie ’66 has written in Gentlemen and Scholars, Princeton was one of a number of Northeastern colleges that, by 1914, had made a transition from ethnic (here, Scottish and Scots-Irish) and denominational (here, Presbyterian) identity to appeal to a new, national upper-middle class. Social distinctions still mattered. Yet Princeton’s esprit de corps depended on cohesion, which in 1914 seemed in turn to demand uniformity. In his incisive 1910 survey of American universities, the scientist-journalist Edwin Slosson found that Harvard sought “diversity”; Princeton, “homogeneity.”

In Hibben’s Princeton as in Wilson’s, intramural athletics as well as varsity sports brought the college together. Princeton’s sometimes-bloody rituals were in part intended to cultivate “manliness and determination,” as Brooks writes, but they were far more for bonding. Princeton’s Honor Code depended on the solidarity of self-identified gentlemen. Most administrators elsewhere doubted such programs could work.

Still, behind Princeton’s conformity there was more diversity than met the eye. Three upperclassmen of the era represented its range: the Class Day orator, Julius Ochs Adler 1914; the athletic superhero, Hobey Baker 1914; and the striving journalist, James Vincent Forrestal 1915.

As elected spokesman, Adler represented Princeton’s present: a national fusion of regional elites. His family were leading newspaper owners and citizens of Chattanooga, Tenn., an industrial boomtown of the New South; Adler was a member of the Southern Club, and his extended family had both Union and Confederate connections. He also was the only member of ’14 to list his religion as Jewish in the class Nassau Herald. Adler’s uncle Adolph Ochs had acquired control of the ailing New York Times in a brilliant campaign in 1896, and his parents hoped their son would be Adolph’s successor. In his history of the Times, Gay Talese describes Adler as “broad-shouldered, chesty ... aggressive and direct.”

Adler had absorbed the ideals of national service that literally were preached to the students by President Hibben, an ordained minister as well as a philosophy Ph.D. In his Class Day oration, Adler, probably thinking of ongoing violent protest in the Colorado coal fields and elsewhere, warned against populism and labor’s clamor for more democracy, giving ancient history a patrician twist by suggesting that the Greek city states had lost their freedom by overextending citizenship.

If Adler was the spokesman for his class’s elitism, Baker, a native of Philadelphia’s Main Line, represented its gallant, gentlemanly heritage. The star of Princeton’s football and hockey teams, he had become a national hero through his apparently effortless grace and his consistent sportsmanship. The proletarian readers of the yellow press may have embraced the class struggle at work, but off the job they devoured accounts of the privileged but intrepid football stars of the Ivy League and helped pack the stadiums. In 1914 the Yale Bowl’s 50,000 seats made it the largest amphitheater since ancient Rome’s Colosseum.

Baker was not as financially privileged as he seemed. In the turmoil of the prewar years, even the One Percent was not always secure. The Philadelphia textile business of Baker’s father had suffered serious losses following the Panic of 1907, and Hobey was able to attend Princeton only because his older brother, Thornton, a fellow graduate of St. Paul’s School, had volunteered to forgo college. Hobey was born to be a sportsman of independent means. He was aware that the code prevented him from accepting offers to play pro hockey. Like other Ivy League athletes of the era, he regarded professional players as “muckers,” a word connoting bad sportsmanship as well as plebeian ancestry. The amateur rule of the Olympics was enforced rigorously. And Baker, who had kept to a small circle of prep-school friends at Princeton, was ill-adapted to the celebrity culture that was to flourish in the 1920s. Restless in an entry-level Wall Street job that seemed t0 offer little promise of supporting a future marriage and family, he became one of many recent Princeton graduates to volunteer in the First World War.

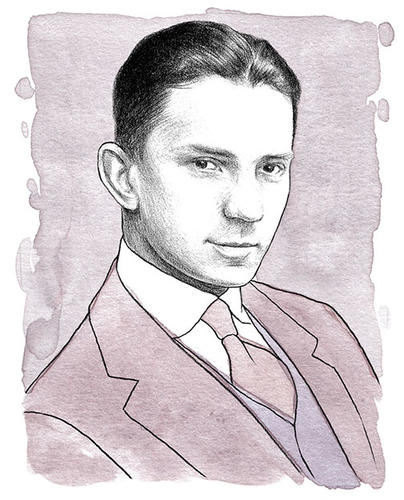

Forrestal represented Princeton’s emerging meritocracy. He was a lower-middle-class Irish Catholic from an upstate New York contractor’s family, accepted as a transfer student from Dartmouth after initial rejection. Forrestal had been raised in a religious household. Hoping he would be called to the priesthood, his devout mother disapproved of his choice of a worldly college with deeply Protestant traditions. But for the son of an economically insecure but politically ambitious Democrat — his father once hosted the rising young Franklin D. Roosevelt — Princeton held the key to real power and wealth. Like F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917 after him, he understood and exploited the loophole in Princeton’s system of boarding-school old-boy networks, cliques, and eating clubs: friendships and powerful sponsors could open doors.

With the support of influential juniors, and after months of systematic networking in which he had introduced himself to every member of his class, Forrestal was elected to Cottage Club. Meanwhile, with the same systematic pursuit of success — as a Daily Princetonian reporter he studied cycles of campus issues to help scoop competitors — Forrestal rose to editor-elect of the Prince. Later in 1914 he co-edited an anthology of the best college journalism to inspire student writers to more serious and thorough treatment of campus and national issues. As an undergraduate, he enjoyed provoking classmates with Marxist ideas, and he delivered critiques of Princeton’s social order to bemused Cottage Club friends (though after World War II, as the first U.S. secretary of defense, Forrestal was fiercely anti-communist).

Forrestal was a new kind of Princetonian, passionately ambitious yet detached, well-read and worldly, familiar with each classmate’s background yet still voted “the man nobody knows.” Later, after a fencing accident, he’d also enjoy the tough image of an unrepaired broken nose.

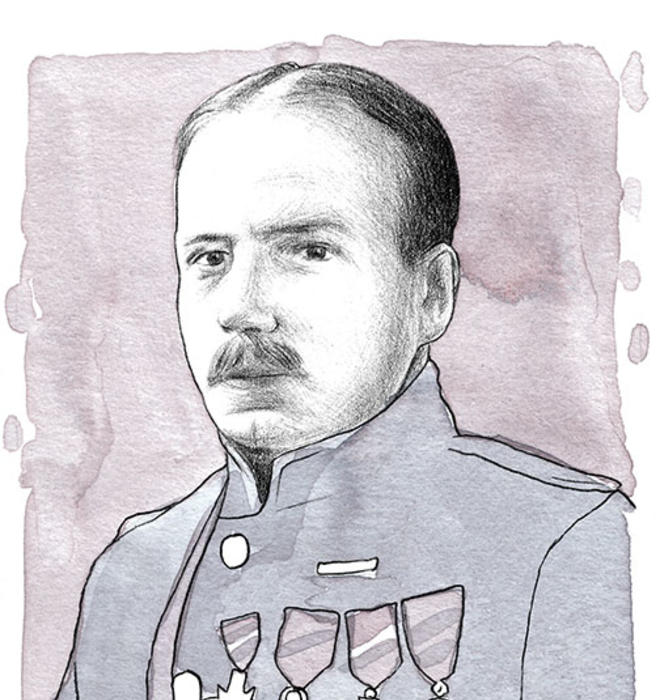

In the First World War, the difference between the three Princetonians’ service records was telling. Baker compiled an outstanding record as a wartime aviator in the Lafayette Escadrille, as adventurous as a pilot as he had been on the hockey rink; he received the French Croix de Guerre for “exceptional valor under fire.” Adler was a fearless infantry officer, a major leading his troops on with his pistol, capturing 50 German soldiers and winning the Distinguished Service Cross, the Purple Heart, the Silver Star, and the Croix de Guerre. Yet while Forrestal also yearned for combat, his superiors valued him so much as an organizer that he served in a staff position. In the 1920s, Forrestal joined the rising investment firm that became Dillon, Read, before joining the Roosevelt administration in 1940.

The Jazz Age Princeton of the Gatsby era was far from the muscular Christianity of the early Hibben years. The sculptor Daniel Chester French’s Earl Dodge 1879 Memorial, dedicated in 1913 to Wilson’s scholar-athlete classmate and popularly known as The Christian Student, went from pre-war shrine to target of 1920s undergraduate vandalism until it was removed from public display. By 1928, James Truslow Adams (Yale M.A. 1900), an investment banker turned writer, reported in Harper’s that Europeans were asking why “a gentleman in America nowadays seems afraid to appear as such; ... even university men try to appear uncultured.” Gentility was unfashionable, and the stock-market crash a year later made it an anachonism. (One happy surprise was the career of Hobey Baker’s self-sacrificing older brother, Thornton, an honorary member of ’14. If Hobey was the paragon of the late Victorian and Edwardian amateur, Thornton was the prototype of our contemporary high-tech dropout-mogul-sportsman, founding a textile company supplying the burgeoning automobile industry, investing in offshore drilling in Galveston Bay, Texas, and sailing a custom-built 72-foot teak schooner yacht around the world.)

The style of 1914, poised between gentility and aspiration, remains evident, decades after Princeton began re-creating itself as the more diverse, modern campus it is today. Its literary monument may be just three lines quoted from a poem by the classicist Herbert Edward Mierow 1914 in the early ’20s and later engraved over the entrance to McCosh 50, still Princeton’s premier classroom:

Here we were taught by men and Gothic towers

Democracy and faith and righteousness

And love of unseen things that do not die.

Edward Tenner ’65, the author of Our Own Devices and Why Things Bite Back, writes and speaks about technology and society.

No responses yet