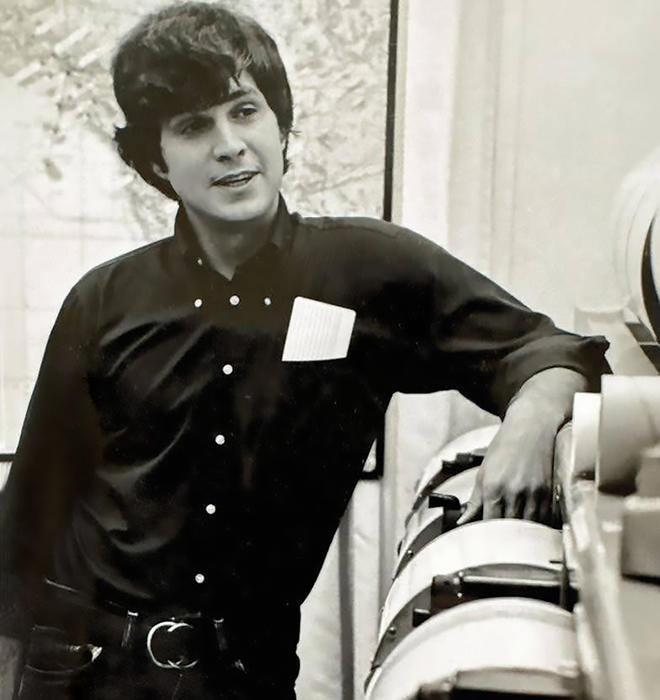

Thomas C. Hanks ’66 Changed How We Understand Earthquakes

Friend and fellow geologist Tom Holzer ’65 called Hanks a terrific conversationalist with “tremendous integrity”

On Oct. 17, 1989, Tom Hanks ’66 was in line — a long line — to get a beer and maybe some ballpark snacks when the ground began to shake.

He was at Game 3 of the World Series between the San Francisco Giants and the Oakland Athletics — an incredible experience for a guy who loved baseball and lived in California. But the San Andreas Fault had its own plans.

People ran in all directions. Hanks, a career geologist specializing in seismology, thought of his two daughters waiting back in their seats.

“Everyone left the beer line, and my dad and his friend just went straight to the top, got their beer, and then they made their way back to the seats. Because they figured we were fine, and we were,” says Julia Hanks ’01, remembering how they eventually returned, drinks in hand. Baseball, beer, family, and an earthquake to boot: “That game was a combination of everything he loved in one place.”

Hanks spent his career at the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, California, where family and friends said he loved his work so much, his daughters didn’t realize for a long time that their dad actually had a job. He made many contributions to his field, but ironically the one that’s best known is the one he’s hardly known for at all.

In 1979, Hanks and his Caltech professor Hiroo Kanamori created a way to measure earthquakes more accurately than with the scale that Charles Richter developed in 1935. The Richter scale measures earthquakes by the destruction they cause or their readings on a seismic instrument, which both make for a fairly imprecise measurement.

Hanks’ and Kanamori’s moment magnitude scale, on the other hand, ties the magnitude of an earthquake to the actual energy released. “It’s a very good physical way of capturing the size of an earthquake, and that’s what we still use today,” says Princeton geology professor Jeroen Tromp *92.

Yet strangely, even after the new scale officially replaced the Richter at the USGS in 2000, no one called it the “moment magnitude scale.” They used the new measurements but kept calling it the Richter scale.

The “Hanks-Kanamori” scale just doesn’t have the same ring, PAW wrote in 2006. And Hanks, modest and curious with a great sense of humor, didn’t mind.

“He never touted anything about his athleticism or his seismology contributions,” says his brother, Jim Hanks ’64. Tom captained his high school baseball and football teams and played rugby and soccer at Princeton. “I once said he was a shoulder shrug about those things,” Jim says.

Tom and Jim were two of three brothers who attended Princeton; the youngest, John Hanks ’69, a professor emeritus at the University of Virginia School of Medicine Department of Surgery, died in October.

Tom followed his geological engineering major at Princeton with a Ph.D. in geophysics from Caltech. At the USGS, he did important work measuring earthquake activity by the scarps, or land breaks, they cause, and on evaluating the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste disposal project in Nevada that was studied by geologists but never built, says Tom Holzer ’65, a friend and colleague.

Holzer says Hanks was a terrific conversationalist with “tremendous integrity.” His daughter Molly Hanks Doyle said she was struck at a USGS memorial by how many female colleagues said he was a mentor to them, particularly back when there were fewer women in science. “One woman said your dad took the time and believed in my work, and few people did,” she says.

As much as he loved his work, Hanks always made time to come home for dinner, attend PTA meetings even when he was the only dad in the room, and host visiting geologists when they came to California and needed a place to stay. Later, he cared for Peg, his wife of 52 years, when she became ill. Holzer says Hanks adored her.

“It was very clear at the memorial we had for Tom that his daughters really cherished him,” Holzer says. “You could tell it was a very healthy family.”

Elisabeth H. Daugherty is PAW’s digital editor.

No responses yet