For Tigers Remembering the 1980 Olympics, 2020 Rings Familiar

With the Tokyo Olympics postponed from this summer to 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, athletes who planned to compete are in limbo. For some 1980 U.S. Olympians, it’s a familiar feeling.

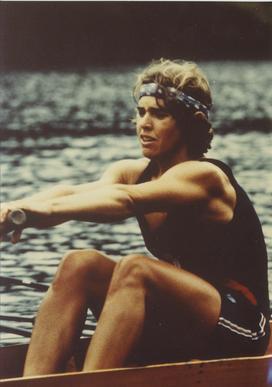

That summer they were forced to miss the Olympics in Moscow when the U.S. led a boycott to protest the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. Though the circumstances are different, the “sense of loss and grieving” for a life-changing goal that had started to feel within reach is similar, said Carol Brown ’75, who qualified for her second U.S. Olympic rowing team in 1980.

“You put your life on hold,” said Brown, who was part of a bronze-winning U.S. team in the women’s eight at the 1976 Montreal Games — where women’s rowing made its Olympic debut — just a few years after taking up the sport as a Princeton freshman. “The price you pay emotionally, physically, financially, is huge.”

Staying motivated is harder when you’re training “with the notion it might be to no avail,” said Anita DeFrantz, another member of the 1980 U.S. women’s rowing team and 1976 bronze medalist. A recent law school graduate, she worked at Princeton, advising students interested in law, while training with members of the national team in the run-up to the Moscow Games.

Other Princetonians qualified for the Moscow Games as athletes or coaches, including Anne Marden ’81, who would go on to become a two-time silver medalist in women’s rowing, competing at the 1984 Los Angeles Games and 1988 Seoul Games.

At least initially, the 1980 athletes had remained optimistic they would find a way to compete, Brown said. DeFrantz filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Olympic Committee, attempting to block the boycott. Other athletes, including Brown, soon joined. They also considered competing under the Olympic banner until officials threatened to revoke athletes’ passports if they tried to violate the boycott.

It helped that athletes weren’t taking in round-the-clock news coverage like the kind accompanying the pandemic.

“You could just kind of tune it out, and our coaches were really good about just saying, ‘Keep going,’” Brown said.

When the boycott stuck, deciding whether to try for another Olympic team four years later was a tough call. Brown took a full year off before deciding to give the 1984 Los Angeles Games a shot and made the team as an alternate. She’s still active in U.S. rowing and advised Tokyo hopefuls to take a similar step back while weighing what’s next.

“Try to do the self-analysis: Can I live with this if I leave it now?” she said. “Take some time every day where you get up and you’re not dictated by eight hours of someone else telling you what to do in training. And does that feel good, or do you need it?”

Brown and DeFrantz, who is a vice president of the International Olympic Committee’s executive board, agreed there is one key distinction between 1980 and 2020: Both disagreed with the decision to boycott the 1980 Games, but neither had any doubt postponing the Tokyo Games was the right call.

“It’s no one’s fault, it was the right decision. You don’t have that frustration that this never had to happen,” Brown said.

Unlike in 1980, where DeFrantz felt the U.S. "used its citizens as pawns," proceeding amid the pandemic wouldn't have been safe, she said.

“I really do feel for those athletes, because I do know how I felt, and it kind of lines up with what they’re feeling now, with one difference,” DeFrantz said. “They’re doing something important for the world this time.”

No responses yet