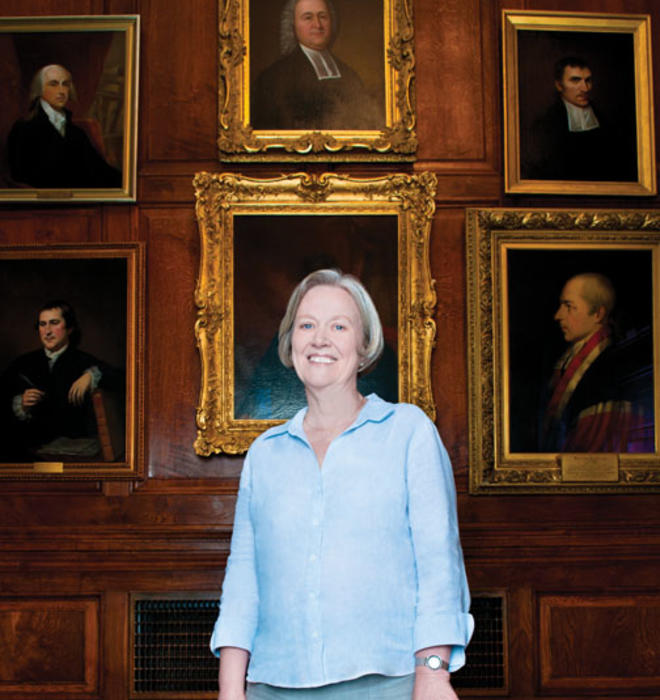

Tilghman at 10

In June, Shirley Tilghman marked one decade in office, leading the University through times of both boom (Whitman College, Lewis Science Library, and new academic programs) and bust (budget cuts and layoffs). PAW editors Marilyn Marks *86 and W. Raymond Ollwerther ’71 spoke to her for an hour in July about what she has accomplished and what remains to be done. (Tilghman also spoke at length with PAW on her fifth anniversary: See the Sept. 27, 2006, issue.) Among other topics, Tilghman addressed Princeton’s financial situation, admissions, problematic town-gown relations, grading, and the aftermath of the suicide of lecturer Antonio Calvo in April. Here are excerpts of the discussion, edited for clarity and brevity.

We’d like to start with what you view as your greatest accomplishments and challenges, and whether your priorities have changed in the last five years.

If I think about the things that have happened in the last five years that I am particularly pleased about, I would have to put in that category the impact that the Lewis Center has begun to have on the life of the campus. It’s the engagement of students and faculty — not just in the Lewis Center, but also the intersection between the Lewis Center and academic departments: the most famous examples being the great collaborations with the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures and the music department over the Pas d’Acier and then Boris Godunov. We’re going to have another extravaganza next February: Eugene Onegin is the third in this trilogy of great Slavic masterpieces that are being re-introduced to American audiences.

Background: Simon Morrison *97, a professor in the music department, has spent the last five years reviving three of Sergei Prokofiev’s works. In 2005, under his direction, “Le Pas d’Acier” was performed in the Berlind Theatre for the first time since 1931; in 2006, he oversaw the world premiere of “Boris Godunov” at the Berlind.

I think the Lewis Center is being realized in the way that I hoped it would. Obviously, it is also one of the biggest challenges we have right now, which is to ensure that the expansion in its space — which is absolutely essential — can be realized. This has been an enormous challenge politically — as opposed to in a fundraising way or in a design way. It’s really been largely a political challenge with the community. We’re hoping that this will be resolved certainly by the fall. And if we can’t resolve it at the site that we have proposed — at Alexander Road and University Place — we’ve already begun planning for an alternative site.

I am really thrilled by what has happened in the Center for African American Studies. The blueprint for how we imagined African-American studies at Princeton — as not a closed enclave, but an idea that would be realized all over campus — I think has really happened. And it’s happened largely by identifying brilliant young scholars who have come to Princeton and are now in the Department of Art and Archaeology and in the Woodrow Wilson School and sociology and English, and on and on, and yet at least some fraction of their academic life is spent interested in issues of race and how it intersects with American life.

The next category is what is happening in both environment and energy. The Princeton Environmental Institute, which preceded my coming into office, has expanded and enlarged opportunities for students who are interested in and concerned about environmental issues. [PEI director] Steve Pacala reports that 20 percent of the graduating class took classes or had internships or summer research experiences in PEI. That’s an extraordinary accomplishment. And what Emily Carter is beginning to do with the new Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment [as its director]: Her focus initially is clearly going to be on alternative energy and issues related to energy like the development of storage batteries — for a very good reason. We’re already very strong in environmental issues, but we need to strengthen our portfolio in energy. I see these two entities — along with the STEP [Science, Technology, and Environmental Policy] program in the Woodrow Wilson School — as a three-legged stool that puts Princeton very much at the center of the work that universities and not-for-profits and governmental agencies are going to be doing in the future to solve what I think is going to be one of the biggest challenges.

And, of course, if you could imagine the day that I went down to the neuroscience building and was able to push the plunger (at least metaphorically; I actually pushed the button to explode the bedrock) to get the neuroscience and psychology building under way at a time we were really last summer still very much in the depths of the recession, thanks to a handful of enormously generous alumni who were willing to help us out. If you watch the strength of both the neuroscience certificate program, which is growing every year, and the new Ph.D. program that is attracting stunningly good students, the educational mission of the neuroscience institute looks as strong as the research mission, which is world-class.

So these are things I continue to watch. They’re works in progress, none of them is fully formed, but I think they’re all launched and launched well.

You touched on the financial crisis. How do you see Princeton’s position today, compared to the days before it unfolded?

I know it sounds like a cliché, but I think we’re actually much stronger today financially than we were before the recession — not because we have more money, but because we are much more disciplined about how we allocate our resources and prioritize them. The famous saying, “A crisis is a terrible thing to waste” — we did not waste this crisis, and that was very important. There are a lot of people who deserve the credit for that, beginning with the provost [Christopher Eisgruber ’83] and [executive vice president] Mark Burstein and [vice president for finance and treasurer] Carolyn Ainslie, who led the strategy for how to take 15 percent out of our operating budget, no small feat in an institution that is very labor-intensive. But we have now put in place programs and initiatives that are intended to maintain the oversight of how we spend money, the goal being not to make everybody do more with less, but just be alert to the fact that there are efficiencies that we can achieve that would then provide more resources for our primary mission, which is teaching and research.

Background: As the dollar value of Princeton’s endowment declined 22.7 percent in the year ending June 30, 2009, the University approved two years of budget cuts totaling $170 million and a reduction in endowment spending by 8 percent a year for two years. Princeton borrowed $1 billion to avoid selling endowment assets at sharply reduced prices. Faculty hiring slowed; about 200 staff positions were eliminated, including 43 layoffs, and salaries were frozen for all employees paid $75,000 or more per year. Nearly $1 billion was cut from the University’s 10-year capital plan.

I think the major thing that the recession forced us to do — and I think we’re better for it — is to know in great detail what those endowment accounts are and what the donors’ intents are, and we’re very careful that those intents are being respected and that we’re mobilizing the income effectively. Some of this is simply by educating department managers and department chairs, who often are responsible for spending that endowment income. There are centralized systems that are now in place so that we can monitor them more effectively.

Are you concerned about the percentage of the University’s operating budget that is supported by the endowment, which has been very high compared to Princeton’s peers?

Roughly 50 percent of the operating budget comes from the endowment. In what I would describe as good times, this is an enormous strength of the University, and it is a strength that is greatly wished by our peers who are much more dependent on tuition, for example. Tuition has now become a relatively modest percentage of our revenue. But coming up against the loss in our major source of revenue made us very sensitive to the need to have a very diversified revenue stream in the University. The trustees are very focused on this. [We’re] very conscious of the fact that sponsored research has become a greater and greater percentage of the operating budget as well, and it is vulnerable; it is not something that one can depend on year in and year out, and we’re living through a period where it’s probably going to be really undependable for the next few years. We’ve strengthened corporate and foundation relations, so that we’re in as good a position as we can possibly be to capitalize on both foundations that are very generous to universities and corporations that are increasingly outsourcing research to universities. That brings with it its own set of complicated issues; [you must] know what those are and negotiate them up front. We’ve had very successful partnerships with companies like BP and Ford and Merck, and we’re looking for additional opportunities to have those kinds of relationships in the future.

Do you have any indication about what’s going to happen with government funding cuts and how that will affect Princeton?

Fundamental research, from the basic all the way to the applied, has always had fairly significant bipartisan support in the Congress and in all administrations — Democratic, Republican. But those resources do come out of the discretionary part of the budget, and that is the part of the budget that is decreasing every year. It would be prudent for us to assume that for the next few years, budgets from the federal government, which is our biggest sponsored-research fund source, will either be flat or in slight decline. It means basically two things: We have to be really competitive for what grant dollars are out there, which means having the very best faculty and students we can. And we have to size our operation appropriately. So, for example, in the heyday when the NIH [National Institutes of Health] was doubling, a successful investigator could imagine increasing the size of his or her lab every single year, because every single year there were more resources. So you hire more postdocs, you assume you’ll get more grants; it was one of these exponential-wise things. It would be very foolish to run your lab like that now.

One thing that is certainly important to Princeton is the $1.75 billion Aspire campaign. With a year to go, it’s reported that the University has raised about 85 percent of the goal.

I think about it in terms of how many dollars we have. So we have to raise about $250 million.

What’s the outlook?

I am cautiously optimistic. The reason is, that’s what we raised this year — very close to that. The last year of the campaign always has a bit of a lift — because people who have been waiting to think about their gift have to make up their mind, and because we have extraordinary donors who often already have made a campaign gift, but come back and make a second gift. So I’m cautiously optimistic that we will get it done by next June.

We mentioned town-gown relations earlier, but it certainly seems that they’ve become more strained over the past year. How did it come to this point?

Background: Over the past four years, the University has been planning a $300 million arts-and-transit neighborhood near McCarter Theatre to create a new home for the Lewis Center for the Arts. One aspect of the plan has divided the community: a proposal to move the Dinky, Princeton’s beloved train, 460 feet south. Public opposition to the Dinky’s move has left the plan in jeopardy.

Well, if I look at it from 30,000 feet, as opposed to try and get into the weeds of whether moving the Dinky 460 feet is a travesty or not, I think virtually all local governments are feeling the pinch as their state allocations decline and their incomes are declining, and this puts tremendous pressure on community representatives to look for alternative sources of income. So I think that it’s almost inevitable when you get into a recessionary phase that there will be increased tensions between the community and the University.

How did you feel your presentation on the University’s arts-and-transit-neighborhood proposal went when you appeared at a meeting of borough and township officials at the end of January? Did it spark better discussion, or did it set things back?

I think the most important thing from my perspective is that it sparked discussion and action. We were in what in biochemistry we call a futile cycle. Futile cycles are terrible in biochemistry, and they’re terrible when you’re trying to get decisions made. It became very clear to me that there had to be some kind of disruption in the futile cycle, and that I was probably in the best position to deliver that disruption. So I don’t think, frankly, we had a choice.

Did it have the result you had hoped for?

It certainly did. There has been a lot more action on the part of both the borough and the township since that meeting than I think we would have even begun to see had we not stated clearly that, if we could not get the decision from the community in a reasonable length of time, we were going to move the [arts-and-transit] project elsewhere.

Have you seen any improvement in relations?

I think we have very good working relationships with the [regional] planning board and with the township, and our relationship with the borough continues to be the most difficult one.

The discussion then turned to the report of the Working Group on Campus Social and Residential Life, which in May recommended a ban on freshmen joining the Greek system and creating a campus pub, among other strategies to improve campus life. Tilghman’s comments are included in an article on her endorsmement of the recommendations on page 14.

How do you view the University’s relationship with the eating clubs today, compared with when you became president?

I think the trend has been enormously positive. We have worked very hard to find ways to embrace the eating clubs. They are part of Princeton — legally isn’t the issue; they are part of the University — and it matters enormously to us that they serve the interests of students. I think this year we’re going to work very hard to institute the recommendation of the eating-club task force with respect to the altered selection mechanism. We just couldn’t get it done last year. If you’re going to do a new experiment, you want it to be done right. The program is now written, the bugs have been identified and removed, and we’re very hopeful that we can try it out this February.

Background: A task force report on the eating clubs recommended modifying the club-selection process; a new plan was deferred in January, shortly before the start of bicker. Under the proposal, bicker at the five selective clubs would be unaffected, but every student who registers would be guaranteed membership in one of the 10 clubs. The process resembles the matching process used to place medical students in residency programs.

You’ve been critical of some of the downsides of bicker. Do you feel that this proposal goes a good way toward meeting your concerns about the selection process?

I think the right way to say it is that it goes part of the way. It is not a panacea, and it will not eliminate all of the downsides of bicker, but it’s a step in the right direction.

The Antonio Calvo story still is drawing attention in the media. Does the University see it as a closed case, or are policy changes being considered? Is there any follow-up plan, either with the family or in terms of policy?

No, there are no plans for follow-up with the family. The family has not expressed any interest in communicating with us. [Dean of the Faculty] David Dobkin is revising the text of our policies that are published in [Rules and Procedures of the Faculty of Princeton University]. Not because those changes will represent a change in policy, because our policy has remained the same, but the policy written in that document and on the Web is, I think, less clear than it could be, and it is clearly in the interest of our senior lecturers and our faculty to have those policies written as clearly as possible. So there will be some editing of policies, but not changes.

Background: Antonio Calvo, a senior lecturer in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese Languages and Cultures, committed suicide April 12. Calvo had been placed on leave and was facing the loss of his U.S. visa at the time of his death. Students and other Calvo supporters questioned Princeton’s handling of the case.

Students requested — and perhaps some faculty members also signed on — an independent investigation …

No faculty asked for an independent investigation.

So, just the students. Is anything happening with that?

No.

Have you communicated that to the students?

Yes.

We would like to discuss issues that relate to diversity and equity in three different areas: the graduate school, the faculty, and undergraduates. When we met five years ago, you talked about your commitment to increasing diversity on the part of the faculty and of the graduate school. We looked at the 10-year change in the numbers for tenure and tenure-track faculty positions: The percentage of women has increased from 21 to 26, and for all minorities, from a little over 13 percent to about 16.5 percent. How do you view that progress?

Disappointing progress. I would have liked to have seen those numbers higher than they are. And I think David Dobkin feels the same way I do, and is talking about how to provide further incentives to the faculty to try and get those numbers moving a little faster.

What kinds of incentives?

Well, we have had a Target of Opportunity committee for a long time. Its effectiveness was affected by the recession; there were several years where we were doing relatively little hiring, and so it’s no surprise that we made relatively little progress. David is talking about monitoring faculty searches much more carefully and intensively than we have done in the past — so that, as searches are under way, members of his staff are looking to see how diverse the pools are, how diverse the short lists are, and whether the faculty is really paying attention to this issue. And closing down searches where there is evidence that there has been no attention paid whatsoever to those issues.

When we spoke five years ago, there had been an increase in minorities among the entering Ph.D. students. Over the last couple of years, the number of underrepresented minorities has decreased, and the yield also has decreased. Do you have any sense of why this is happening?

The overall numbers are discouraging, but there are some real success stories. One of the things we need to do is learn from those success stories. So, if you look at the numbers in molecular biology — it happens to be my own department, but it also happens to be where the greatest progress has been made — there were a handful of faculty who three, four, five years ago decided to make this their highest priority, and they have made immense progress. They have created summer programs in collaboration with some of the historically black colleges, like Spelman and Morehouse. They have very aggressively gone out and recruited underrepresented-minority graduate students. And their numbers are tremendous. So I think the lesson from molecular biology is — as Linda Loman said in Death of a Salesman, “Attention must be paid.”

Despite some improvement in the numbers, Princeton continues to rank last among the Ivies in percentage of Pell Grant recipients, while the most affluent students statistically seem to be overrepresented. Is Princeton doing everything it can to improve socioeconomic diversity, and why does it lag behind its peers in this area?

I think there are a couple of challenges for us. One is our historic reputation, which is that we are a place of privilege, and that continues to haunt us: the continued perception that Princeton is a place for people of wealth or at least well-being. And that is going to take a couple of decades before we can finally put that to rest. Some of that is our failure to effectively communicate the fact that we have led the country in providing the kinds of resources that a Pell Grant-eligible student would need in order to come here. Some of it has to do with the attractiveness of cities for that particular group. Our Pell Grant numbers went up this year again, which I was extremely happy to hear, but I think there’s still more that we can do.

Is Princeton going to all the schools that it should visit to recruit students? I often hear lower-income, working-class kids say, “No one from Princeton has ever come to my high school in Middlesex County, N.J.”

The answer is that probably we’re not doing enough; we’re not getting to enough of those high schools. There is nothing like the personal touch. We can have Twitter and Facebook stories out there until we’re blue in the face, but there’s nothing quite as powerful as a visitor from Princeton, a public face. This is a role that our alumni could really help us with. Mobilizing our schools committee to be more active in visiting those schools and talking and encouraging those students who are qualified to apply to Princeton, I think, would be a wonderful thing.

One could argue that Princeton turns away 91 percent of all the students who apply. Couldn’t it just choose to admit more students from this group?

You know, at one point I asked [Dean of Admission] Janet Rapelye if she leaves [the applications of] any low-income students who could do the work at Princeton on the table, and her answer is no.

There are that few who are applying?

What we have to do is work on getting the word out more effectively.

What do you think will be the impact, then, of Princeton’s return to early admission this fall? Because that has a lot to do with information.

I’m very worried about it. Janet Rapelye is absolutely persuaded that we can sustain the progress that we have made since we eliminated early decision, but I think it is going to be challenging for us.

What have you heard in response to the report on women’s leadership? How do you answer critics who might say, “Well, the University shouldn’t be doing social engineering.”

It’s really been fascinating to hear the response to the report. I think the responses, as I would expect of any Princeton report, have been very diverse: from women who said, “I recognize absolutely everything that is in that report ... I recognize it in my life, I recognize it in my children and what my children are going through, and the differences between my sons and my daughters,” who believe that the report has described something that is real and substantive and that is important for a university to think hard about; to people who say exactly what you said, which is they don’t see a problem, they don’t understand what the issue is, that by singling out women’s leadership, you’ve already done harm to women, that women are competing on an equal playing field now, and [to say that] that women need special attention is to ignore the fact that 60 percent of college students today are women, and what we should be doing instead is focusing on what is happening to boys. We’ve gotten a whole spectrum, and that’s good. If there were consensus, this would have been a really boring report.

Background: In 2009, President Tilghman set up a steering committee to explore “how students define and experience leadership and ... whether women undergraduates are realizing their academic potential ... at the same rate and in the same manner as their male colleagues.” In a report released in March 2011, the committee found that women generally were underrepresented in the most visible campus leadership positions and among recipients of the most prestigious academic prizes.

Are you seeing a generational difference in those responses?

I think women from the ’70s and the ’80s, of course they’ve lived that many more years, but they resonated to the report much more than recent graduates. And certainly there are current women students at Princeton who literally just don’t believe there’s a problem and don’t understand what the whole thing was about. And there’s a part of me that celebrates the fact that they feel completely empowered and can’t believe that there are women out there who don’t feel equally empowered at Princeton. I think the worry is that they’re going to face a world that’s going to look a lot harder than they think it’s going to look.

Are anti-grade-inflation efforts here to stay, or with a new dean of the college might there be a review?

I’m going to leave that to Dean [Valerie] Smith, who is going to, I’m sure, have her own thoughts about grade inflation. But the one thing that I would say about the current policy: It is the fairest grading policy we have ever had at Princeton, and if we were to revert back to where we were seven or eight years ago, you would have to look at the data and say that we were grading in a highly unfair way.

Do you mean the differences among the departments?

There needs to be a way of ensuring that a student who concentrates in comparative literature is neither advantaged nor disadvantaged relative to a student who concentrates in physics. They should have an equal chance, if they do excellent work, of receiving an A, and if they don’t do excellent work, of not receiving an A. That was not the case seven years ago.

When you agreed to be a founding trustee of the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia in 2008, you said you wanted to encourage expanded opportunities for women in a region “where historically they have not been available.” How successful do you think you’ve been, how many times have you gone there, and when you go there — given the regulations and the customs — have you covered yourself?

I’ve been there twice. Because it’s an international board, we meet all over the world. I have not covered myself; I have refused to do so. And, so far, there has been no consequence for that.

The [Saudi] university itself has really lived up to every promise it made upon its founding. A quarter of the student body are women, and that’s in a university that is focused on science and engineering at the graduate level, so that’s actually a very good number. It’s having more difficulty attracting women faculty, and that’s hardly surprising. The men and women students are living and studying and playing together on equal footing, and the women graduates of the university are getting jobs in the kingdom.

After (men’s lacrosse coach) Bill Tierney and (men’s basketball coach) Sydney Johnson ’97 left the University to coach at other schools, some alumni raised the question, “Is Princeton willing to pay what it takes to keep its top coaches?” Should they be concerned?

I think that we are in the most privileged place in Division I athletics, which is in the Ivy League. And the Ivy League has to date resisted the enormous pressures that exist outside in Division I to compensate coaches at levels that are often multiples of the salary of anybody else at the university. Once you go down that path, there is no return. And so, no, Princeton is not willing to participate in the salary arms race.

What is on your list of things that remain to be accomplished during your presidency?

I think the most important thing this year is completing the Aspire campaign and having it be a successful campaign, like all the others we’ve had. I think ensuring that the new initiatives are really on the strongest possible foundation: the neuroscience institute, the Andlinger Center, the Lewis Center. All of the new international initiatives like the bridge-year program — these are really on a stable footing, and we’re assessing their success on a regular basis.

One of the major things that I’m going to spend some time thinking about this year is how can we better realize the potential of our residential colleges. In my 10 years, we’ve made enormous investments in those colleges: building Whitman College, rebuilding Butler College, and changing the dining strategy in the colleges. It is my sense that we have not yet realized their full potential, and that’s why I was so interested in some of the ideas that came out of the social task force this year, because I think that committee was really trying to grapple with the fact that those colleges don’t yet really feel as though they are the homes of the juniors and seniors as much as they are of the freshmen and sophomores. And I don’t mean literally, but metaphorically.

Do you see a formal initiative taking place or a different kind of approach?

I think we’ve had enough formal initiatives, and I don’t think that the six colleges have to march in one step. I think it would actually be quite interesting to have one college decide it’s going to try this set of things and another college trying something different, and let them differentiate themselves from one another.

Do you have a time frame for accomplishing all of this?

I really don’t. I am still very much engaged (and) extremely happy doing what I’m doing. I still feel as though I have a lot of energy, and so I’m just going to play it by ear for the next few years and hopefully have a very good internal barometer of when it is time for me to step down. I do not believe it is appropriate to overstay your welcome — bad strategy. And I hope I have enough common sense and a board that is capable of being frank with me, that I will know when it is the right time.

No responses yet