Deborah A. Kaple *91 teaches in the university’s Writing Program.

Last spring, two novel events took place on the Princeton campus. On the fifth of May, 29 students assembled on the stage of Taplin Auditorium, then one by one stepped forward to sing unaccompanied, their mouth shaping the rounded, majestical notes of African-American congregational songs.

Many of the songs had come into existence during a semester of intense give-and-take between student singers and songwriters in Humanities 498, a workshop directed by Bernice Johnson Reagon, founder of the a capella group Sweet Honey in the Rock, and her musician daughter, Toshi Reagon.

A few weeks later, across campus in the James M. Stewart ’32 Film Theater at 185 Nassau Street, students in Humanities 499, a workshop in documentary filmmaking, gathered with filmmaker Louis Massiah to present their works in progress. The students had been working for the last two months with Massiah and his associates Charlene Gilbert and Carlton Jones on two film projects involving the Princeton Nursery School and a local outreach organization, Save Our Kids.

Both workshops were part of Princeton Atelier. The program is the brainchild of Toni Morrison, a Nobel Prize-winning novelist and Robert F. Goheen ’40 *48 Professor in the Council of the Humanities, and since its inception three years ago it has brought together scores of students, faculty, and visiting artists to explore the collaborative process in the visual arts, literature, dance, film, theater, and music.

The idea for the Atelier (French for an artist’s studio, and pronounced ah-tell-yay) came to Morrison in 1991, when Carnegie Hall commissioned her to write the lyrics for “Honey and Rue,” a piece scored by André Previn and sung by soprano Kathleen Battle. The artists worked on the project together. Collaborating with Previn and Battle, explains Morrison, whose work incudes six novels and several books of literary and social criticism, taught her to “stretch and freshen” her skills as a writer. “It was such an extraordinary experience for me that I wanted to have it again, and I wanted somehow to pass it on to students.”

From the start, Morrison wanted the Atelier to encourage experimentation – she viewed it as “an opportunity to get all of the parties into a situation where one person didn’t know everything, to see what would happen.” The Atelier bridges the worlds of professional art and academia, and is a haven and crucible for artists and students alike. For the artists it can be a place to play with ideas beyond the scrutiny of critics. For the students it is an opportunity to share in a creative synergy in which the process becomes an end in itself.

The Atelier reflects Morrison’s thoughts about learning and creativity. “I don’t like to arrive at a certain plateau and stay there. If something isn’t challenging or compelling or new in some way, I lost interest. I like to be in the position of being an amateur in some regard, so that I can learn from people who are not amateurs.” Atelier courses are not just for humanities majors and students pursuing certificates in the creative arts. Last spring’s workshops included students majoring in engineering, economics, computer science, and biology.

In a larger sense, the experimental nature of an atelier makes everybody an amateur, for the professionals can’t entirely foresee the outcome; a kind of leveling occurs, and students and artists alike feel responsible for the end result. Says cellist Yo-Yo Ma, who helped lead an atelier in 1996, “It’s an experience that nobody will ever, ever forget.” Last year the Atelier was awarded a grant from the university’s 250th Anniversary Fund for Innovation in Undergraduate Education.

“Disciplined and Messy”

The first Atelier took place in the spring semester of 1994 and brought to the campus choreographer Jacques d’Amboise, the director of the National Dance Institute and a former principal dancer with the New York City Ballet, and fiction writers A. S. Byatt, known for her finely crafted novels Possession, Angels and Insects, and The Virgin in the Garden. Their goal was to compose, with the help of students, a dance inspired by Byatt’s Possession. As typically happens in an atelier, students who are used to being told what to do initially found the experience unnerving. Elizabeth Belton ’95 recalls the first sessions as “frighteningly unstructured and unpredictable.” Morrison expect this reaction from students and says to them, “It’s going to be very very disciplined and very messy.”

With Byatt’s novel as an inspiration, some of the students wrote poetry, while others composed music; then they joined together to translate these efforts into dance. D’Amboise, who says his philosophy is “the best way of learning is by doing,” put the students immediately to work, assigning nondancers to dance and poets to paint scenery. He also involved local children in the project, including some who were living in welfare motels on Route 1, near Princeton. In 10 weeks, the members of this diverse team put together an entire production – interpreting Byatt’s words into dance; creating the lighting, sound and choreography; and coordinating the performances of kids and adults. In Belton’s view, the experience was memorable for “the way we all took what we found and put it to use, and the way we dealt with any eventuality.”

Morrison insists that the professionals who come to Princeton be genuinely interested in working with students. “The artist, at least for this amount of time, must be totally committed and willing to take each student seriously,” she says. The Atelier has sparked an array of mentoring relationships between students and artists. Notes Ellen Goellner, the program’s assistant director, “The artists who take part in ateliers do so by making time they don’t have. They fit their teaching into their professional touring and production schedules. We’ve had guest artist show up in formal concert attire for their Friday afternoon atelier because they’d be dashing off to perform with the New York Philharmonic the same evening. Others have invited students to sit in during their rehearsals. An atelier student gets to see the artist’s working world up close.”

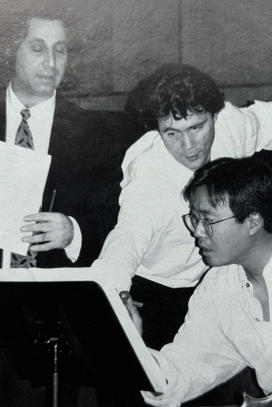

Morrison herself sets the standard for the commitment between teacher and student. In the spring of 1996, she codirected with Yo-Yo Ma an atelier that brought together student poets, composers, vocalists, and musicians to create and perform musical works. Joining Morrison and Ma on the faculty were composer Richard Danielpour and bassist Edgar Meyer. Their efforts were collaborative on several levels. The artists worked with the students, the students worked with each other, and Morrison and Danielpour worked together to set to music Morrison’s lyrics for a piece titled “Sweet Talk: Four Songs on Text,” which premiered last April at Carnegie Hall.

Danielpour and Meyer teamed with student poets and composers on setting words to music, Morrison guided the poets in crafting lyrics, and Ma helped everyone on composition and production. Danielpour asked composers to “really listen to the poem” and insisted that the poets “listen to what the composers are about, so that it really becomes a collaboration.” As Meyer recalls, “Working with the students – who were all spectacular – was really stimulating. It reinforced for me that composition comes from revelation, which you get by working together, discovering new things.”

For an example of collaboration the students looked to Morrison and Danielpour. “I needed to spend time with Toni before I could start composing,” says Danielpour. “I found myself listening to the rhythm in her voice, the rhythm of her language, her sense of humor, which is prodigious. All of these things are part of the poem.”

As for the students, “We didn’t feel like we were novices or were doing something that wasn’t worthwhile. The artists had the same sort of expectations of us that they would have had of people who were doing this professionally,” said Tom Ford ’97, a classics major. “They seemed to be operating under the assumption that we were capable of doing something of genuine artistic worthiness, and they were careful not to step on us creatively.” Ford’s “Homeward: Three Songs” was set to music by composer Wei-Drin Lee ’97 and performed by soprano Christy Pichichero ’98, with Erin Habelt ’97 on clarinet, Ma on cello, and Lee on piano. In hindsight, Ford calls the experience “amazing” but daunting. “It was frightening for the poets to stand over the composers’ shoulders and watch what they were doing with our poems.”

A theater and writing atelier offered that same spring exposed students to the work of Peter Sellars, an avant-garde director of theater and opera, who was joined by Wen-Yi Hua, a Chinese opera singer; filmmaker Carma Hinton; and Susan Pertel Jain, a scholar of Chinese theater. Sellar’s aim was to explore with students a 16th-century Chinese opera, The Peony Pavilion, by Tan Xianzu. He assigned the students to read the opera, then divided them into six groups to compose scenes based on it, which they ultimately had to fit together into a coherent whole.

Minds vs. Hearts

Sellars, who teaches performance seminars at UCLA and Berkeley, found his Princeton students intense and cerebral, inclined to listen to music with their minds rather than their hearts – a process he was determined to reverse. For their part, the students assumed that this celebrated artist had come to Princeton to direct them in a performance. “I thought the atelier was going to be ore of his project,” recalls Jeremy Caplan ’97, a Woodrow Wilson School major. But Sellars had no intention of directing them in anything. As he told them, “I know what my voice is, and this class is about finding your voice.”

One of Sellar’s goals was to help the students discover for themselves the relevance of this 16th-century Chinese text to their late 20th- century American lives. Their viewing of Hinton’s documentary on the Tiananmen Square uprising, The Gate of Heavenly Peace, and her lecture on the 1989 student revolt were central to the course, as were demonstrations and workshops in Chinese opera. “The point of the Atelier wasn’t to restage a museum work,” says Morrison. “The students adapted scenes from the opera to their lives and the lives of the audience. As with every atelier, the critiquing was relentless and ongoing and enabled students to develop a vocabulary to talk about their performances and what they were trying to convey.”

All this was in preparation for their performance on the last Saturday of the semester. But as the date approached, Sellars showed no concern about polishing performances or how the individual sections would fit together. The students were perplexed by his seeming nonchalance, and on the morning of the performance a few were close to panic. Sellars remembers that when he arrived at the rehearsal that afternoon in the Matthews Acting Studio, at 185 Nassau Street, “they expected me to pull it together and I didn’t.” To get the students to stop thinking of the stage as their proprietary space, he insisted that they perform in the seating area while the audience sat on the stage. “Then I turned a few things upside down and left for the rest of the day.” That evening, Sellars returned to the studio to view the performance as a member of the audience. He found the experience “moving and beautiful, because they had no choice but to listen to each other, to be attentive to something that was happening outside of themselves. They had to literally cooperate.”

In what some of them dubbed an “unclass,” the students had created their own production one with a rare spontaneity and emotional power. As senior Vanessa Lemonides said at the end of the course, “For the first time since I came to Princeton, I can think not about hitting someone else’s mark but about hitting my own mark. It takes confidence, and I think the ease and the lack of pressure and the flow of energy in this project enabled us to find that.”

Crucial to the development of the Atelier, according to Morrison, who is the program’s fund-raiser, have been gifts from alumni and other friends of the university. Initial funding came from the Samuel I. Newhouse Foundation. The chief donor is Peter T. Joseph ’72, who learned of the program during discussions about a collaboration between the Atelier and the American Ballet Theatre, which he serves as chairman; he is seeking to ensure the Atelier’s continuation through establishment of an endowment. Other supporters include Dennis J. Brownlee ’74; the Frelinghuysen Foundation; and Universal Studios Foundation, whose gift was arranged by Universal chairman Frank J. Biondi ’66. The Atelier also depends on the cooperation of the university’s established art programs. Next spring it will offer an atelier with the American Ballet Theatre and a workshop led by Joyce Carol Oates, the Roger S. Berlind ’52 Professor in the Humanities, and director Susana Tubert.

Says Yo-Yo Ma, “Toni’s on to great things. The Atelier is the essence of what a university can be about.” And as one student wrote in a course critique, “The Princeton Atelier has been one of those few classes that has succeeded in breaching the barrier of factual scholarly knowledge and truly educating me. It has changed the way I view and interact with ideas: rather than augmenting my intellect, my atelier experience has rearranged it.”

This was originally published in the Sept. 10, 1997, issue of PAW.

No responses yet