Our University predates the United States of America, so it is appropriate that Firestone Library contains almost bottomless riches from every period of the nation’s history. Some of the very best are on view in an exhibition called “A Republic in the Wilderness: Treasures of American History from Jamestown to Appomattox,” in Firestone’s Main Gallery.

The exhibition displays nearly 100 items, some of them never shown before. At least one, a wanted poster for John Wilkes Booth after he assassinated Lincoln, was seemingly unknown to anybody, languishing in a box in the depths of the library until it was discovered by chance several weeks ago. The great difficulty, says Don Skemer, Firestone’s curator of manuscripts, was to narrow down the selection: “Our collections are so rich, we could barely scrape the surface.”

Skemer long had wanted to launch such a show, but the opportunity finally arose with a gift from Margaret Nuttle of Virginia, a descendant of the patriot and orator Patrick Henry and mother of the late Philip E. Nuttle Jr. ’63. Before her death in 2009, she established the Barksdale-Dabney-Henry Fund to support the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections in highlighting early American history. Appropriately, the show is formed entirely of materials already in Princeton’s collection, and includes a 1778 letter in which Patrick Henry warns settlers not to encroach on Cherokee lands.

The exhibition’s title, “A Republic in the Wilderness,” refers to an 1866 description of the early nation by historian George Bancroft. Skemer and the show’s curator, Anna Chen, have woven together the country’s political life and its spectacular natural environment. Manuscripts, letters, maps, broadsides, and photographs all are included. “It was an immense pleasure to discover one treasure after another,” says Chen. “I’m still finding things I wish I could have put in the show.”

George Washington is well-represented, from a 1750 survey he did of his brother’s land in Virginia, to a draft of an inaugural address he never gave, to a list of his slaves. Also on display is one of the approximately 175 letters by Abraham Lincoln that are in the library’s possession: Writing to Francis Preston Blair shortly after his election, Lincoln makes clear that federal forts seized by seceding states before his inauguration must be retaken. There are numerous Princeton connections: artist John Trumbull’s sketch for his painting “The Battle of Princeton”; Louis-Alexandre Berthier’s map of the town at the time of the Revolution, showing a certain “Collège”; a poetry manuscript written by Annis Boudinot Stockton, about all she saved after Cornwallis’ troops ransacked her home, Morven.

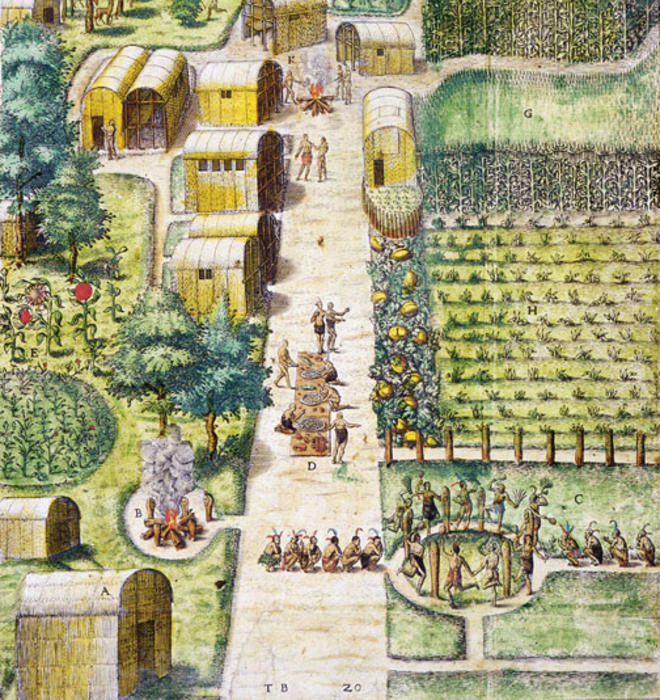

The show prompted curators to conserve many items, including the 423-year-old, hand-colored engravings that accompany William Strachey’s eyewitness account of the Jamestown colony. “They were all folded six different ways,” Skemer says, “and all had to be reinforced.”

The show’s organizers are hard-pressed to pick their favorites. Skemer likes the “Plan of West Point” by Berthier, who drew more than 100 maps of the epic march of Rochambeau’s army south to Yorktown in 1781. Chen singles out the poignant contents of a wallet belonging to Capt. Isaac Plumb, a 2012 acquisition. The wallet was in his pocket when he fell, mortally wounded, at the Battle of Cold Harbor in Virginia in 1864, fighting with the Union Army in a battle noted for its purposeless slaughter. Among other things, the wallet held a telegram and letters from home, which are far rarer than letters from the front, Chen explains.

“That is of considerable interest, to see these items belonging to Plumb, who lost his life in one of the most dispiriting of battles,” says Princeton professor emeritus James McPherson, perhaps the nation’s most renowned Civil War scholar.

Chen does not disguise her excitement over the project. “It’s a very rare opportunity to see treasures of this magnitude in one room,” she says. “I hope that visitors will experience some of the excitement I felt when I was assembling them.”

The exhibition will remain on display through Aug. 4.

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 is the author, most recently, of Princeton: America’s Campus (Penn State Press).

William Strachey sailed to Jamestown in 1609, arriving in 1610 after surviving a shipwreck and spending months in Bermuda with others, constructing ships in which to continue to Virginia. He became the Virginia Company’s secretary to the troubled 3-year-old colony. On display is a contemporary manuscript of Strachey’s eyewitness account, with his handwritten corrections and signature. It includes 27 hand-colored engravings of American Indian life, made by Theodor de Bry late in the 16th century. Depicted here is the Algonquian village of Secotan in what is today North Carolina; the engraving was based on a watercolor by artist John White, who would become governor of the abortive attempt at a permanent settlement on Roanoke Island. Woodrow Wilson 1879’s classmate Cyrus McCormick gave Princeton this priceless artifact.

Princeton owns two albums stuffed with more than 1,000 mounted photographs of American Indians. The haunting albumen prints seen here, taken between 1847 and 1865, show Sac, Fox, and Dakotas. Their names evoke a bygone world: Op-Po-Noos, Cut Nose, Bum-Be-Sun, Ma-Za-Ka-Te-Mani, Medicine Bottle; the sixth is unknown. Some photos were taken on the Great Plains; some when Indian delegations visited Washington. All were compiled, it is thought, by renowned Western photographer William Henry Jackson.

We associate Thomas Jefferson with his advocacy of the sturdy American farmer — linchpin of democracy, the economy, and society. From 1774 until his death in 1826, Jefferson kept meticulous records of his agricultural activities at Monticello, as well as a census of his slaves and their allotted woolens and supplies. Among the names listed in this Farm Book are those of Sally Hemings and her children Madison and Eston — now believed to have been Jefferson’s flesh and blood.

“In many ways it was the most traumatic event of the entire war,” historian James McPherson says of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre. An enormously valuable cash reward is offered by this broadside, which gives descriptions of the villains, including Booth: “Black hair, black eyes, and wears a heavy black moustache.” Some of the names are spelled wrong, suggestive of the frantic immediacy of the event. “Let the stain of innocent blood be removed from the land by the arrest and punishment of the murderers,” the poster urges.

Modern media coverage of warfare began with the albumen prints taken by Alexander Gardner, which brought grim reality home to millions. His images of the aftermath of Antietam in September 1862 suggest the battle’s horrific cost: 23,000 soldiers killed, wounded, or missing in the bloodiest day of all American history. This photograph belonged to Gen. George B. McClellan, commander of Union forces. His son, George B. McClellan Jr. 1886, later donated it to Princeton.

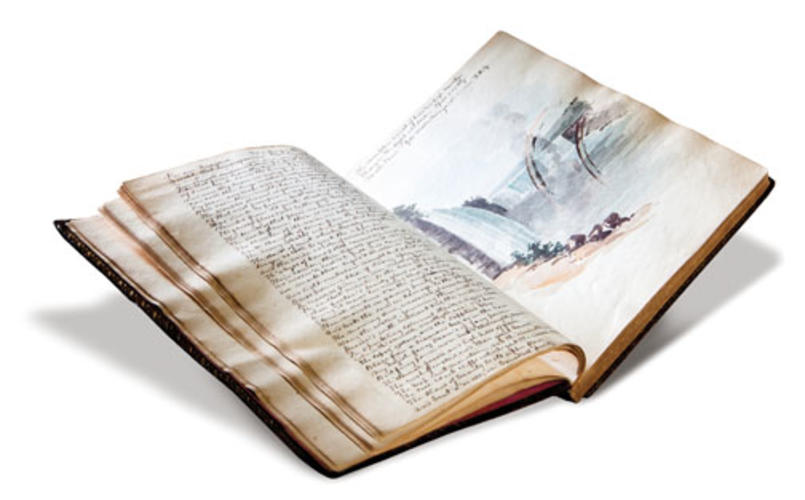

Niagara Falls fascinated Americans with its immense scale, dwarfing anything Europe had to offer. The daughter of a New York City judge, Anicartha Miller, asked acquaintances to contribute poems, sketches, and mementos to fill her friendship album around 1827. The artist George Catlin, later celebrated for his depictions of Plains Indians and the American West, provided a watercolor view of the falls, which created a cloud of vapor that could be seen for miles.

ITEMS FROM THE EXHIBIT “A REPUBLIC IN THE WILDERNESS: TREASURES OF AMERICAN HISTORY FROM JAMESTOWN TO APPOMATTOX,” COURTESY DEPARTMENT OF RARE BOOKS AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, PRINCETON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY; PHOTOS: RICARDO BARROS (JEFFERSON’S FARM BOOKS, WANTED FOR MURDER, THE GREAT CATARACT)

No responses yet