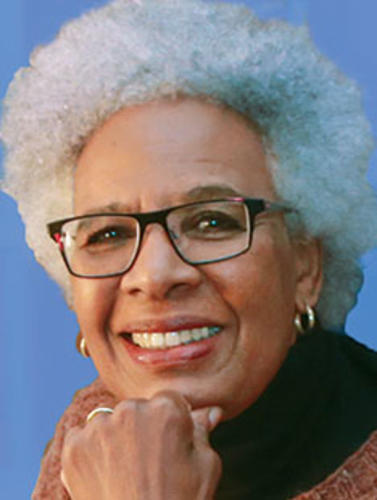

Historian Nell Irvin Painter is history professor emerita at Princeton and the author of seven books, most recently The History of White People.

Donald J. Trump campaigned on the slogan “Make America Great Again,” a phrase whose “great” was widely heard as “white.” Certainly the election has been analyzed as a victory for white Christian Americans, especially men, especially the less educated. Although a cascade of commentary since the election has characterized the outcome as a loss for Democrats, Hillary Clinton received the majority of votes — almost 2.9 million more than for Trump. Against Mr. Trump were women, people who had attended college, young people, and middle- and working-class people of color. Trump’s supporters increasingly have been labeled by class — working class.

Though white Americans differed sharply on their preferences for president, the election of 2016 marked a turning point in white identity. Thanks to the success of “Make America Great Again” as a call for a return to the times when white people ruled, and thanks to the widespread analysis of voters’ preferences in racial terms, white identity became marked as a racial identity. Formerly seen as individuals expressing individual preferences in life and politics, white Americans in 2016 became Americans with race: white race.

I don’t mean that Americans suddenly started counting people as “white.” This has been going on since the first federal census of 1790. Since 1790, population statistics have faithfully recognized a category of “white” people, sometimes more than one — especially native and non-native born, for in previous centuries, the census divided white people into subgroups according to nativity. We did not suddenly discover the category of white in 2016.

I’m saying that what it means to see yourself as white has fundamentally changed, from unmarked default to racially marked, a change now widely visible: from of course being president and of course being beauty queen and of course being the cute young people selling things in ads to having to make space for other, non-white people to compete for those roles. Conveniently, for most white Americans, being white has meant not having a racial identity. It has meant being and living and experiencing the world as an individual and not having to think about your race. It has meant being free of race. Some people are proud white nationalists, but probably not many of the millions who voted for Donald Trump.

Thinking in terms of racial community would seem to be the job of black people. So for many white people the change is a demotion. We have been seeing this change creeping into popular culture and in higher education over the last few decades. Black and brown and Asian people sell you financial instruments and clothing. The former president and first lady are black. College literature courses include Toni Morrison and Junot Díaz. But according to many interviews before and after the election, people who haven’t gone to college — where multiculturalism has been making its way for a generation — felt they had a lot to lose, as did millions who retained an image of America formed in the 20th century.

From assumed domination, white people now take their place among the multiracial American millions. For Trump supporters embracing the social dimension of “Make America Great Again,” their vote enacted a visceral “No!” to multicultural America — as if to say: Take us back to the time of unmarked whiteness and racially unmarked power, assumed to be white.

The Trump campaign disrupted that easy freedom and identified his name, and hence his administration, with a white identity. The Trump administration is one of white men in charge (including a U.S. attorney general whose embrace of white supremacy previously denied him a federal judgeship). You could say that’s nothing new, that white men have been in charge forever. This is true, but now with a gigantic difference. This time the white men in charge will not simply happen to be white; they will be governing as white, as taking America back, back to before multiculturalism, or, as many would prefer to term it, before the reign of political correctness.

In addition to a white racial identity, the billionaire-laden Trump administration comes with a paradoxical class identity: working class as white. Time and time again, recent commentary has labeled his supporters not only “white,” but also “working class.” According to a line of thinking that has become popular among some Democrats as well as many journalists, Democrats “lost” the presidential election because they disregarded the legitimate, class-based needs of the white working class — as though class-based needs precluded any place for racial resentments, as though economic grievances obscured the Republican Party’s history of Southern strategy, birtherism, “you lie!” and anti-immigrant posturing.

The logic of white-working-class grievance has two weak points. First is the discrepancy between an electorate’s class-based needs, on one hand, and Republicans’ favorite policies privileging tax cuts over job creation, on the other. Second is the logic’s inability to recognize the existence of working-class Americans who did not vote for Donald Trump. Millions of working-class voters who favor Democrats are white, but in the discourse, it would seem that Democrats lack economic and class interests of their own. Democrats are seen either as elite liberals who disdain working-class whites or as members of racial-ethnic minorities whose main concern is political correctness. Jobs would seem not to be among their main concerns. This narrative flourishes even though Hillary Clinton’s campaign devoted far more attention to policies that actually would increase the number of jobs in the United States, for instance, in renewable energy.

Describing the electorate this way means assigning class only to Trump voters and identity only to people who are not white, and it totally ignores the history of Republican governance — or, rather, non-governance — during the administration of President Obama. Thus, talking about the concerns of working men and women means talking about Trump voters and jobs, while talking about people with “identity” means talking about issues of political correctness. It’s as though working-class Americans who are not white cannot have a class identity or economic interests related to class, for they have only racial identity or, even more narrowly, a racial identity connected to political correctness. The distinction here counts, because political correctness is a cultural issue, while jobs are an issue of economic policy.

The reluctance to see people of color as people with class status, seeing them as workers, has centuries of historical precedent. Historians seldom characterize the antebellum enslaved as a class of unpaid workers; the great 20th-century migrations out of the South are more commonly conceived of as racial phenomena than movements within the American workforce. By removing people of color from the working class to which many of them belong, today’s narrative suggests that jobs and financial security are interests of white voters only, voters who identify as Republican. This locates the economy in the purview of the Republican Party, which throughout the Obama presidency blocked policies intended to benefit working people. Today’s narrative of blaming Democrats for neglecting working-class interests steadily ignores the congressional Republican role. This blindness may be about to change.

Now that congressional Republicans are in charge of governing, the white-working-class-Trump-supporter narrative may run up against actual policymaking. The great test case is the Affordable Care Act, which Republicans immediately began working to repeal. Here is a policy affecting working-class Americans of every race and ethnicity whose repeal will not spare those who are white. How repeal will translate into discourse and electoral preference remains to be seen.

7 Responses

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoThere is a reason the white...

There is a reason the white working class (rural and urban) was easily brought over to the pro-slavery side, even though slavery was detrimental to itself. I am not permitted to give you the reason by the politically correct masters who run this blog. But if you think about it, you will get the answer.

Nikki Ourand Lambert

9 Years AgoAfter eight years of the...

After eight years of the Obama administration's neglect of issues that matter to people of color, it's disingenuous to suggest that a Clinton administration would have done any differently, especially considering the tone-deaf pandering of her campaign. And the Democratic Party has been complicit in making America white again, at least since the Clinton administration.

At the heart of the division in the US is class. Those in power—in both parties—are members of and represent the 1%. We the People are damned either way. Vote Republican and die quickly, or vote Democratic and die incrementally.

AJ Matlak

8 Years AgoThanks, Nikki, for making...

Thanks, Nikki, for making this argument. I've been trying to explain this to many people for years, and you summed it up in two short paragraphs. I always say that back in the cold war days, we always heard that the Soviet Union and other communist countries were one-party states. Well, here in America we have a two-party state that instead of being devoted to Marxist/Leninist thought is devoted to capitalism. Sure you can call the president anything I want but if you really try to change the dynamic, look out, you might get squashed like a bug.

Charissa Grace White

9 Years AgoNot really getting where...

Not really getting where that other comment is coming from...maybe the article cut too close to the quick for him.

Great thinking here, truly enjoyed and am challenged by this.

Mary Shepard

9 Years AgoA shrinking white demographic...

A shrinking white demographic has made the white working class into a minority. Sadly, they are the only ones visible to the media and everyone else. We think the working class are coal miners in West Virginia.

Jack Adrian

9 Years AgoSuggesting that political...

Suggesting that political correctness has no bearing in an economic sense? I don't find that very reasonable.

J. Regan Kerney ’68

8 Years AgoDemocrats Need to Learn Empathy

Published online July 6, 2017

Professor emerita Nell Irvin Painter (essay, March 1) offers a curiously superficial analysis of Donald Trump’s election. The story is more complex.

Consider Wisconsin, which twice went for Barack Obama and chose Bernie Sanders in the Democratic primary. After Hillary Clinton drove Sanders from the race, Wisconsin turned to Trump in November. How did a Rust Belt state that twice chose a black president, and then turned to a socialist, suddenly become white supremacist in the fall election? The answer is, it didn’t.

Between 2000 and 2016, Wisconsin lost 20 percent of its manufacturing jobs, mostly to technology, although, according to Sanders and Trump, the jobs were “stolen” by Mexico and China. They promised to bring them back. This shameless demagoguery fell on the ears of a – yes, mostly white – class of workers who have been drop-kicked by life into structural-unemployment hell, accompanied by alcoholism, drug addiction, and rising death rates, as the work of professors Anne Case *88 and Angus Deaton has shown.

For whatever reason, Clinton ignored them, and didn’t campaign in Wisconsin. A similar story unfolded in Michigan and Pennsylvania, and losing all three of them cost Clinton the election.

Ever since Clinton wrote off many of Trump’s supporters as “deplorables,” the Democrats have struggled to understand them. Professor Painter’s interpretation, like Clinton’s, could benefit from a modest dollop of empathy. If the Democrats ever want to win again, they need to start listening to these people instead of blaming them for being victims.