IT WOULD SEEM LIKE A VERY HARD phone call to make, the ultimate good news/bad news story. When Eden Full called her parents one afternoon in May 2011, she had a huge achievement to announce — and a real kicker to go with it.

The good news? Full, then a sophomore, just had been awarded $100,000 by the Thiel Foundation, which would enable her to develop an invention that could bring cheap solar energy and clean water to the Third World.

The bad news? The award came with one large string attached: Full had to drop out of college.

Her parents, in Calgary, were supportive, if apprehensive. “Neither of them went to college,” explains Full, a second-generation Chinese immigrant, “and having me finish was a big deal.” So Full attached a condition of her own: She would return to Princeton once her two-year fellowship was over.

When Full — then ’13 and now ’15 — keeps that promise and returns to campus in September, she will be a junior with an unusually deep reservoir of experience. She has founded a business, applied for a patent, traveled the world, and, incidentally, rowed with the Canadian national team. It is a big résumé for the socially minded entrepreneur and coxswain who stands just 4-foot-11.

The Thiel Fellowships were created in 2010 by Peter Thiel, one of the founders of PayPal and the first outside investor in Facebook, whose foundation (as Thiel’s mission statement puts it) “defends and promotes freedom in all its dimensions, political, personal, and economic.” Full was one of 20 entrepreneurs in the inaugural class. Although Thiel himself has multiple degrees from Stanford, he has embraced Mark Twain’s motto that “I never let my schooling interfere with my education.” Many young entrepreneurs, Thiel believes, are wasting their time in higher education and would be better off developing their ideas in the real world. His foundation enables students under the age of 20 to do just that — on the condition that they drop out, although they can take a few classes if necessary for their projects and they are free to return to school when their two-year fellowships are complete.

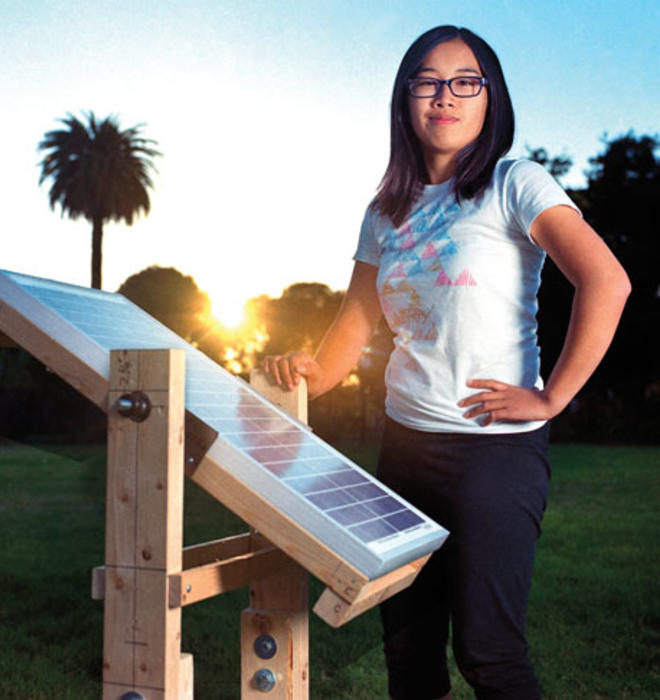

FULL, WHO SEEMS TO BE EXACTLY THE SORT OF young entrepreneur Thiel had in mind, was already an accomplished inventor before she entered college. Growing up in Alberta (she speaks fluent Cantonese but peppers her English with broad Canadian “O”s), she built a solar-powered toy car when she was 10. A few years later, while still in high school, she began designing a device, named the SunSaluter, that enables solar panels to follow the movement of the sun. When she unveiled it at an international science fair, an Indonesian girl remarked how useful such a device would be in rural villages.

“It really got me thinking,” Full recalls. “[I thought], ‘What am I doing sitting here just making this a science experiment when this could actually be something?’” The project became such an obsession that her parents sometimes let her call in sick to school so she could work on it.

The SunSaluter provides a cheap and simple solution to a real problem in many parts of the Third World, where solar power is one of the only practical ways to generate electricity. Because solar panels are stationary while the sun’s position in the sky changes, they only achieve maximum efficiency during the few hours when the two are aligned. By mechanically moving the panels to follow the sun’s progress, Full’s device can increase energy output by as much as 40 percent. Motorized panels do exist, but they can be prohibitively expensive and require a lot of power; the SunSaluter, by comparison, is made of bamboo and metal, costs about $20 to make, and can generate enough electricity to charge a lantern, two cellphones, or a 12-volt battery.

After spending the summer studying climate change in the Canadian Arctic, Full entered Princeton in September 2009 and took a course with Professor Winston Wole Soboyejo on science, technology, and African development. Soboyejo — who has research interests in alternative-energy systems and affordable infrastructure, among other things — served as her adviser as she worked to design sustainable metal buildings through the University’s Engineering Projects in Community Service program. Then, with support from the Princeton Grand Challenges program, Full spent three weeks in Kenya the following summer testing SunSaluter prototypes.

It was on this trip that she got a harsh lesson in the practical applications of technology. A woman in one of the villages told Full that she had three lanterns but only enough electrical power to charge two of them at a time. Full offered to build a SunSaluter and went to a nearby village to buy parts. While she was gone, the woman was trampled by a water buffalo as she searched for firewood in the dark.

“That experience helped me realize that the work I was doing could very tangibly and immediately change someone’s life,” Full recalls. “I think that experience gave me the motivation I needed to take some time off to work on something that mattered to me.”

ON THE DAY THE THIEL FELLOWSHIPS WERE announced, in the spring of her sophomore year, Full was out on Lake Carnegie, coxing for the women’s lightweight crew. When her cellphone buzzed, she looked at the screen and saw a San Francisco area code; she suspected who was calling but decided it would be bad form to take a phone call in the middle of practice. Instead, she nervously waited until she was back on land before returning the call.

Danielle Strachman, program director for the Thiel Fellowships, says that two things helped Full stand apart. Full did not have just a vision for what she wanted to do with the money, she already had begun to develop a product. Her project also presented a technological challenge and addressed a pressing social need — a combination the foundation found particularly attractive. “I would take 10 more of Eden in a heartbeat,” Strachman says.

Although Full attends regular update meetings, the Thiel Foundation places no restrictions on how the money may be used. Full acknowledges that she has spent a good part of her Princeton hiatus pursuing other interests, including backpacking across Europe with a friend. She also spent several months last year rowing with the Canadian national team and racing with the team in London and Amsterdam.

“I realized that it’s hard to be an elite athlete and have a full-time job,” she says, “but I could do my work anywhere with WiFi and a laptop. I’d have 7 a.m. practice, and then I’d work, and 11 a.m. practice, and then I’d work, and 4 p.m. practice, and then I’d work. I sacrificed my social life, but I was living in London, Ontario, so there wasn’t much of one.” Even now, in California, she usually is on the water six days a week, rowing with three different Bay Area clubs.

Full spent many of her nonpractice hours networking for her business, Roseicollis Technologies Inc. (the name comes from the Latin name for Full’s favorite species of lovebird). In addition to the Thiel, Full has received 200,000 euros (about $275,000) as runner-up in the Dutch Postcode Lottery Green Challenge, and smaller grants from Scotiabank and the Mashable/UN Foundation Startups for Social Good Challenge. (Unlike the Thiel fellowship, the other grant money is earmarked for business development.) She also was named the 2011 Staples/Ashoka’s Youth Social Entrepreneur of the Year, which enabled her to meet other entrepreneurs in Indonesia, Kenya, and Egypt.

Full used the time in those countries to deploy and test the SunSaluter, gaining what she calls “market validation” — a determination of need for the product and its best placement and design. She since has expanded her tests to Uganda and Tanzania, and says that donated SunSaluters currently provide electricity to more than 5,000 people in five villages in Africa. “We would put one on exhibition in a public area and wait for people to notice,” she explains. “People would come up to us and ask, ‘Where can we get one?’” Although Full has looked into establishing a manufacturing subsidiary in East Africa, manufacturing now takes place only in the Bay Area. She has hired her first two employees, but the SunSaluter — which still is not for sale — will remain Roseicollis’ only product until all the bugs have been worked out. “Baby steps,” she says. “Baby steps.”

On one of her African trips, Full experienced a eureka moment that helped make her product even more useful. An early version of the SunSaluter was powered by the heat differential between two strips of recycled metal, but Full recognized that the device also could address a second problem in many Third World villages: a lack of clean water. A new model of the SunSaluter has replaced the metal strips with two small metal tanks. Water is poured into one tank and flows through a filter into the second tank. The movement of the water turns the solar panels, and a valve controls the flow so that it matches the rate at which the sun moves. At the end of the day, each SunSaluter produces four liters of clean water as well as solar energy.

SINCE RETURNING TO THE UNITED STATES IN November, Full has lived and worked in an old firehouse, painted salmon and pink, in Oakland’s Chinatown. The building is owned by Danielle Fong *07, who has made it available rent-free as a workspace and dormitory to young entrepreneurs. Fong herself founded LightSail Energy, which makes energy-storage systems. When her business outgrew the firehouse last year, Fong decided to make it available to others — hoping, she says, to re-create some of the communal spirit she recalls from living at the 2 Dickinson St. co-op in Princeton.

The area where fire trucks once were parked is now a workspace dominated by exposed fiberglass insulation, a large flat-screen monitor, drill presses, and a plastics lathe about the size of an old VW bus. A bicycle and a pair of kayaks lean against the wall. Full lives upstairs with four others who are developing their own businesses. The budding entrepreneurs — Full describes herself as a social entrepreneur — organize weekly dinners and allocate housekeeping responsibilities with a chore chart mounted in the kitchen.

“A two-time dropout myself, I knew full well that some of the most exciting and rewarding opportunities were those far from the beaten path.”

Danielle Fong *07

“People basically come in on recommendations,” Fong explains in an email, “and if they’re really cool, doing something we admire, and vibe with us, there might be a space open.” Fong felt drawn to Full, whom she discovered through the Thiel fellowship. “I was very happy to discover such an amazing, energetic young spirit working on an important problem,” Fong says. “A two-time dropout myself, I knew full well that some of the most exciting and rewarding opportunities were those far from the beaten path.”

Full says her two-year break from academics has changed her. “I was really immature in college,” she says. “I spent lots of time rowing and hanging out. I definitely didn’t spend a lot of time on my work. I almost felt that I had to go through college for the sake of going through college. Now I can go back to Princeton not feeling like I have unfinished business in the real world. I already know what I want to do because I took time to explore.”

Although she plans to continue to run her business, Full never forgot her promise to her parents. “I feel that what has helped me keep perspective over the past couple of years is that I set this end goal of going back. Princeton helped me grow a lot as a person. I don’t want to give that up.”

And while her senior thesis is not due for another year and a half, the prospective mechanical and aerospace engineering major already has a topic in mind. It has nothing to do with solar energy or social entrepreneurship. Full says she plans to write about the biomechanics of rowing.

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

No responses yet