Verdun and Back: A Pilot’s Log

Soldiers have been saying since ancient times that it’s impossible to describe the experience of war to those who have not been through it, but Samuel Hynes has spent much of his career trying, almost singlehandedly pioneering war writing as a genre for academic study. Hynes, the Woodrow Wilson Professor of Literature, emeritus, was a Marine Corps pilot in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Six of his 11 books address the subject of war.

Hynes often has drawn on his own experience, as he did in essays in his most recent collection, On War and Writing, published this year by the University of Chicago Press. Following is an excerpt from that collection; it was originally published in the Summer 1992 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History. In the essay, Hynes describes a flight over European battlefields that he made with a friend in October 1990.

Oct. 13 / 10:15 A.M.: Shoreham Airport, Sussex.

The weather is with us, I think as we taxi out to the runway. It is a fine English October morning — bright sun, the sky intensely blue, with thin streaks of high cirrus clouds in the west and a mild wind blowing from the south. Visibility over northern France will be good.

We are setting out, my friend Anthony Preston and I, to fly the length of the Western Front from Ypres to Verdun. It’s high time that I saw the actual landscape of the Great War, since I’ve just written a book about it; and because I was once a military pilot, it seems right that I should see it from the air. Anthony is with me because he loves to fly, likes France, and is better at navigation than I am. The plane is a Piper Warrior — about as fast as a Sopwith Camel or a Fokker triplane, though a good deal more comfortable.

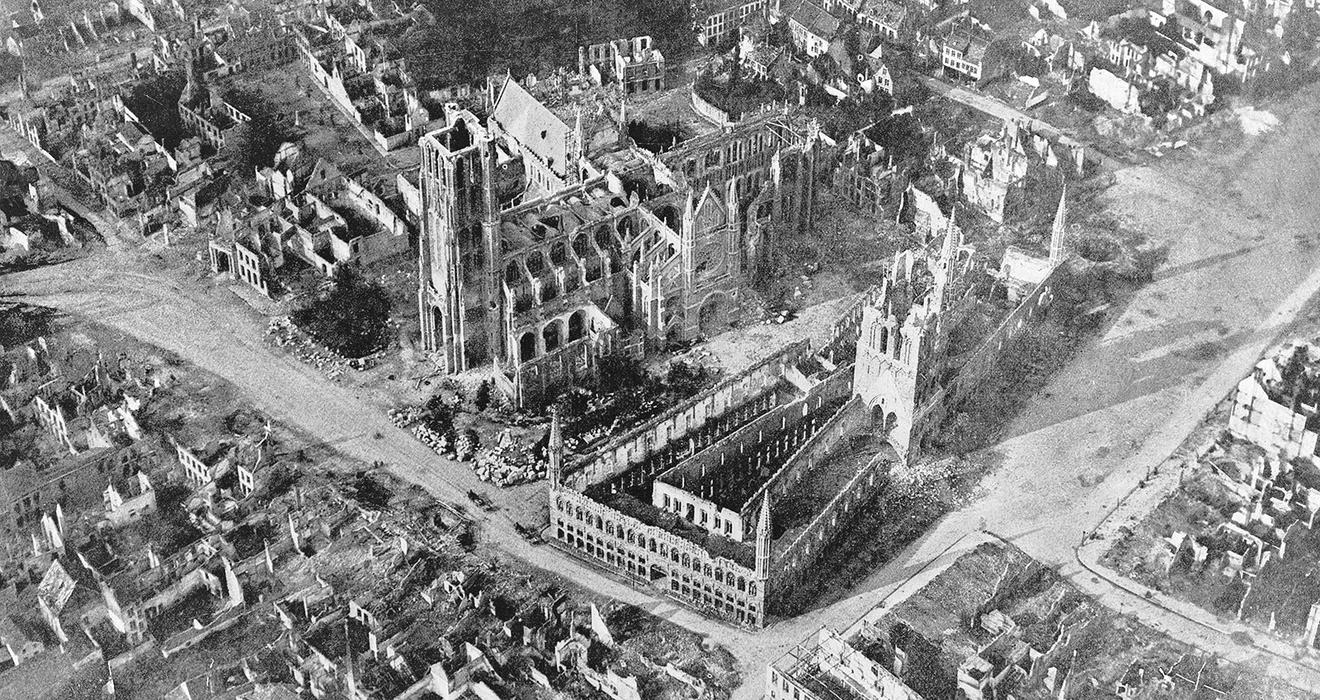

German shelling ruined the old town of Ypres, Belgium (above), in World War I. Flying over the town decades later, Princeton professor emeritus Samuel Hynes, a World War II pilot, found that from 1,500 feet, the town appeared “as it must always have looked.” Only the Menin Gate, England’s memorial to the missing dead, “makes the war present.”

I feel a certain astonishment that we have actually managed to get the project this far, and I half expect something to go wrong, even now. We had talked about such a flight off and on for a long time — where we’d go, and what we’d see — but in the idle way that friends do, over a drink or a meal, not really expecting that it will happen. But here we are, turning into the wind and cleared for takeoff.

Our preparation suddenly seems to me alarmingly casual: I have brought a couple of Michelin road maps, and Anthony has an air navigation chart covered with purple stripes that are restricted areas and circles that are radio beacons. And we have my copy of Before Endeavours Fade, the late Rose Coombs’ wonderful guide to the battlefields, which we hope will help us to find the landmarks of the front when we get there. Anthony, being an ex-RAF pilot and accustomed to these air spaces, is jauntily confident: just up to Dungeness, across to Calais, and straight on for Ypres. A piece of cake, he says.

We take off to the south, and I find myself thinking not about the First World War but about the Second. The British commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Britain not long ago, and down here on the South Coast is where much of it was fought. Shoreham, the field we are leaving, was an air-sea rescue station, and over there to the west, under our wing, is Tangmere, a wartime Spitfire field. And below us is the Channel, where the unlucky and the unskillful pilots in that battle ended their shares of the war.

10:53 A.M.: Dungeness.

This is the point of English land along our route that is closest to France — about twenty-five miles. I bank to the right and head toward Cape Gris-Nez. I am taking the Channel! A commonplace enough thing to do nowadays — the air is full of stockbrokers flying their wives to Le Touquet for the weekend — but I feel an excitement, as though I were Louis Blériot, eighty-odd years ago. We’re a little faster than he was. It took him thirty-seven minutes in 1909, crossing in the other direction, and we’ll make it in fifteen. And we’re a good deal higher — he couldn’t climb above a hundred feet. But it’s the same journey. The sea is calm but cold-looking, and as we leave the land behind I find myself listening to the engine with a particular attentiveness, as one always does over water. Freighters and tankers are scattered over the surface below us, and both coasts are visible all the way, so I don’t feel any of the loneliness that used to seize me as I flew over the Pacific, when there was nothing but water down below. Yet I still have the uneasy feeling that there is no place to land. And then, gradually, the dark smear along the horizon ahead becomes a flat coast, and we are over France.

11:40 A.M.: Calais.

Calais Airport is just a bare, half-abandoned-looking field stretched out beside a long sand beach — one strip and a couple of buildings, one with a squat tower. The controller in the tower is bored but obliging; he directs us to the parking area in slow, careful English. The customs official is hard to find on a Saturday morning, but amiable enough once we locate him. One plane takes off, and its high-pitched sputter fades to silence. Nothing else happens. If limbo had an airport, it would be like this one, and we are glad to get back into the bright air, heading east for Ypres. Somewhere on this leg we will cross over Belgium, but we’ve decided not to mention this fact to the Belgians. Why complicate life? Anthony asks. After all, there is no dotted line drawn across the great plain below us to mark the frontier. It is all Flanders from up here.

Ypres appears as a round town, shaped by the canal that circles it. The ramparts by the Lille Gate catch the midday sun as we approach; in the center of the town the Cloth Hall raises its commanding roof and spire, dominating the lower buildings around it as it has since the thirteenth century. I know from the books that it was destroyed in the war, and that what I see is a postwar reconstruction, but from the air it looks convincingly medieval. The Cloth Hall was built as a vast covered market, but the market seems to have spilled out into the square outside; as we approach we can see that it is full of brightly colored stalls.

Anthony circles steeply round the east side of town, and I pick out the Menin Gate, England’s memorial to the missing dead of the Ypres salient. I can see the British lion couchant on the top, and the long archway under which buglers still sound last post every evening. From the air the gate is solid and heavy-looking, but our altitude flattens it, making it seem less monumental than it must appear from the ground. One important feature of it is invisible to us: the interior panels engraved with long columns of names — 54,000 of them, the names of the British Empire dead in the salient whose bodies were never found. But the knowledge that they are there, like an army of invisible ghosts, makes the massive architectural gesture of the gate seem grandiloquent, false to the real history of the dead. Men who fought in France felt that way about it. The English war poet Siegfried Sassoon saw the gate when it was built in 1927, and he wrote an angry poem about it that ends

Well might the Dead who struggled in the slime

Rise and deride this sepulchre of crime.

Pilots flying over Ypres in 1918 saw a ruined town in which not a single north-south wall remained standing. (The Germans had been shelling from the east for four years.) But to me, tipped up in a plane circling at 1,500 feet, it doesn’t look battered; it doesn’t even look restored. It is simply an old town, looking as it must always have looked. Only the gate — if you know what it commemorates — makes the war present.

North of the town it is different. At the war’s end this was a dead, annihilated space forty miles square, without a tree or a house left intact. There are trees and houses here now, but signs of the devastation remain. Craters begin to appear, most of them filled with water and looking like country ponds, but more exactly circular than a natural pond would be. And the lines of trenches are still scrawled across the fields in white streaks of turned-up chalk that have not yet been erased, even after seventy years of plowing. Here and there, in the middle of a pasture or beside a road, are small military cemeteries, often just a monument and a few white stones, looking as though they had been dropped casually from a height and had fallen every which way. Their randomness offends the strict geometry of the field lines, and the whiteness of the stones seems out of place in the fertile green and brown landscape.

Poelkapelle lies just to the northeast of us, and because there is a monument in its center to the French ace Georges-Marie Guynemer — and because this is a pilot’s pilgrimage — we fly over to pay our respects. It is another case of a monument without a body. Guynemer was shot down, and according to rumor his body was found by German soldiers and carried to a dugout; but the dugout was destroyed by the next artillery barrage, and Guynemer’s remains were lost. The monument is easy to find; it stands like a hub at the center of the town’s bustle. I know that there is a figure of a flying stork atop the tall column — the stork was the symbol of Guynemer’s squadron and was painted on the squadron’s planes — but from the air it is indistinguishable, just a black something. It might be a monument to anybody.

We turn east toward Passchendaele, a name that calls up terrible visions of a senseless slaughter. I try to imagine what the scene below me was like then, in the soaking autumn of 1917 — the rubble of buildings, the smoke, the exploding shells, and most of all the mud, so deep and viscous that men drowned in it. But what I see is simply another tidy, prosperous-looking red-roofed little Belgian town, standing at the crest of a slight ridge in the midst of fields. The town is going about its usual Saturday business; cars are moving about and people are busy in the square. The land around it is dry and solid and well cared for, like any good farming country at the end of the season. It is all a picture of peace.

But south of the town, down a gentle slope, there is a large and unavoidable reminder of the war and its human cost: Tyne Cot Cemetery, shining white in the sun and visible for miles. It is geometrically ordered, with a vast neatness. From our altitude the separate headstones lose their individuality and merge into white rectangles, in strict order, like battalions on parade, forming one huge rectangle. Outside that parade-ground order are ranged other stones in other patterns, looking as though they had been added later by someone with different ideas of what the design should be. Along the front are a few stragglers, scattered as afterthoughts. Placed among the graves are monuments — a tall cross at the center, towerlike structures at the corners — that thrust up from the flat geometries of the stones and seem to govern the scene. In all that white tidiness are the remains of two cement bunkers, dark and shapeless.

It is the graves that impress me. The monuments say Not in Vain and Glory and Sacrifice. But the rows of identical white stones say simply Death, and Death, and more Death. The Menin Gate had uttered only half of that message to us. Tyne Cot tells it all. Around that pattern of the dead, the countryside repeats its own message. Cows are grazing in the pastures, a farmer is plowing, the fields are neat and ready for winter. The life of the land goes on.

From On War and Writing by Samuel Hynes (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 189-94. Copyright © 2018 by Samuel Hynes

1 Response

Richard Seitz ’75

7 Years AgoPictures, Please ...

My thanks for a great story. Would have loved pictures to compare the changes. All the stories on the War to End All Wars were enlightening. I hadn't heard about the Zone Rouge area still contaminated 100 years later. And to think all we worry about is the NFL red zone. My thanks to Samuel Hynes for his service and his story.