A War Brought Home

In his photographs of the Civil War, Alexander Gardner proved the power of an art form coming of age

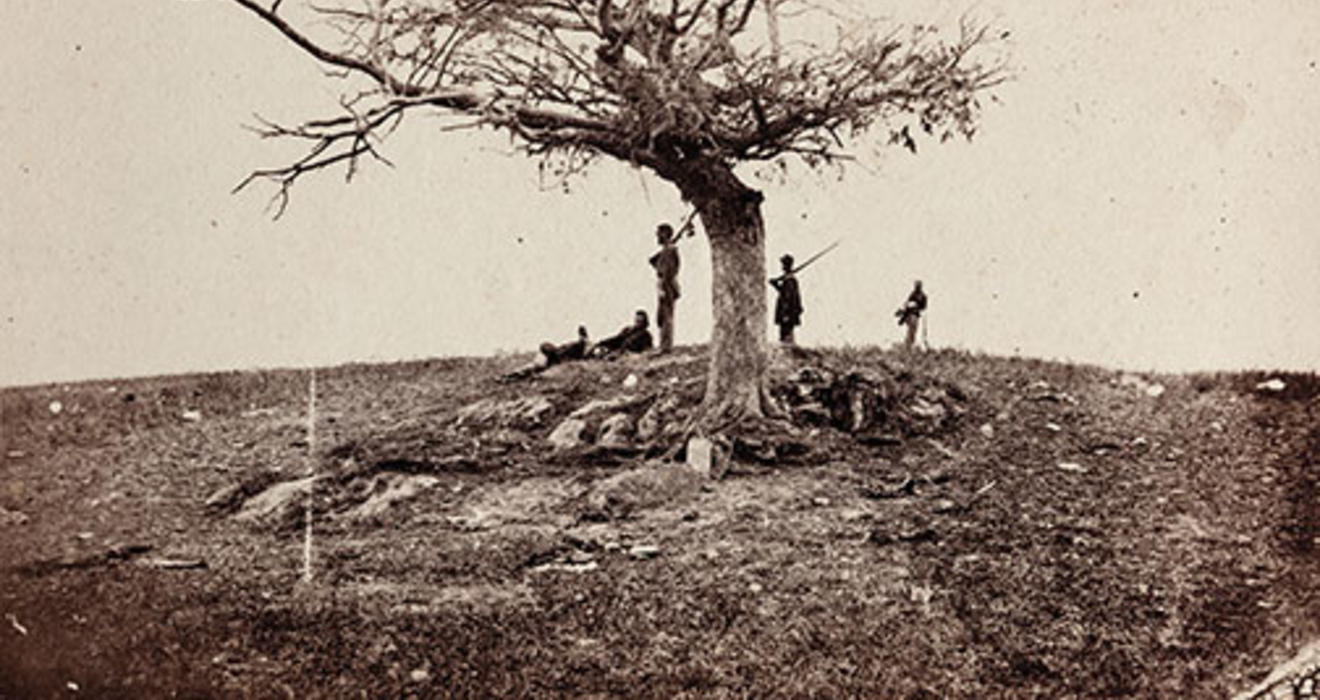

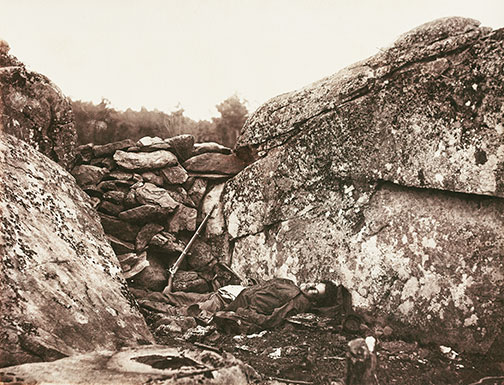

Upon opening to the public in October of 1862, Mathew Brady’s photo exhibition “The Dead of Antietam” caused an immediate sensation. Outside Brady’s gallery at 10th Street and Broadway in Manhattan, crowds stood in line for hours, waiting to gawk with fascination and horror at something they’d never seen before: true images of actual soldiers lying dead on the battlefield. Just weeks earlier, on Sept. 17, Antietam had produced the deadliest single day in the history of American warfare, with about 23,000 soldiers dead, wounded, or missing. The immediacy of those awful pictures left viewers no doubt about the horrors of war: “If [Brady] has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along the streets,” wrote a reviewer in The New York Times, “he has done something very like it.”

Courtesy Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections: Manuscripts Division (McClellan Collection); Graphics Arts Collection (Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book); Photos: Ricardo Barros

When the war began, photography, though no longer in its infancy, was still a rather tame, domesticated art, a substitute for portrait painting — “Rembrandt perfected,” in the words of Samuel Morse. Many of the photographs we have of Civil War soldiers are posed studio shots, so-called cartes de visite, 4-inch by 21/2-inch calling cards that could be collected in albums and shared. Soldiers heading off to battle were eager to leave their families this memento, in case they did not return. Photography studios popped up around the country to answer the demand, and an artist as renowned as Brady, who had made portraits of presidents, generals, and other celebrities, made a lucrative business by producing these keepsakes. “The Civil War gave photography a huge boost,” says James McPherson, Princeton’s George Henry Davis 1886 Professor of American History emeritus. “It came of age during the Civil War as an art form.”

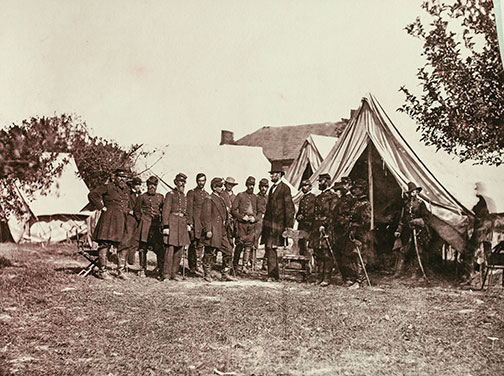

Princeton’s libraries hold a rich assortment of Civil War photographs, including those shown here. Among the more than 100 collections linked to the war are photographs credited to Brady but taken, in fact, by his leading assistant, Alexander Gardner. The Gardner photos appear in two places: in Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War and among the papers of Gen. George B. McClellan. Though these are the best known of Princeton’s Civil War photos, Don Skemer, Princeton’s curator of manuscripts, points out that fascinating images related to the war also are found among collections of personal and family papers, including cartes-de-visite portraits of political figures, Union generals, and foot soldiers from the community.

Gardner printed 200 copies of the Sketch Book; Princeton’s copy, obtained in 2005, is one of just a handful in libraries. The Antietam photos in McClellan’s papers were donated by his son, George B. McClellan Jr. 1886, who would become a New York congressman, mayor of New York City, and a Princeton economics professor. How exactly they came into the general’s possession is uncertain.

Brady took credit for the Antietam photographs, though with his eyesight failing, he had become more entrepreneur than working photographer. Instead, he dispatched teams of his employees to the battlefield, each equipped with a horse-drawn, “dark-tent” wagon in which to prepare the heavy glass sheets for exposure and then to develop them before shipping them back to the studio to be printed.

Prominent among those photographers was Gardner, a restless, wildly bearded 41-year-old Scot who, having tried his hand at a variety of occupations, from silversmith to newspaper editor and even manager of a savings-and-loan business, had turned his attention to photography. Gardner had sailed to New York in 1856 and within months was working for Brady.

Gardner was a most valuable employee. He had become an expert in the new “wet-plate” technology, which, unlike daguerreotype, could produce multiple prints from a single negative. When Brady opened a new gallery in Washington, D.C., in 1858, it only made sense for Gardner to become its manager. When Brady got the idea to make an ambitious photo record of the war, it was Gardner whom he dispatched to Antietam, some 25 miles away, where he traveled with the Army of the Potomac. He was made an honorary captain in his friend Allan Pinkerton’s Union Intelligence Service and spent time between his trips to the battlefield making photographic copies of maps at Union army headquarters.

As powerful as the Antietam photos were, it was virtually impossible to reproduce them widely. The only way for magazines like Harper’s and Leslie’s to spread the images on any scale was to employ skilled draftsmen to produce woodcut illustrations taken directly from photos. “You can find some of these images in Harper’s, and you’ll see how much impact they lose when they’re reproduced for mass distribution,” says Princeton history professor Martha Sandweiss, editor of Photography in Nineteenth-Century America 1839–1900. “This is the beginning of the mass media, but it’s not all the way there.”

The people who flocked to Brady’s gallery never had seen images as stark. There had been photos taken during the Mexican-American and Crimean wars, but they did not show corpses. Miffed by Brady’s taking all credit for the pictures, Gardner quit, recruited many of Brady’s employees, and in 1863 started a rival gallery in Washington.

Making pictures in the field was time-consuming and awkward. The cameras were heavy, the darkrooms cramped, and the chemicals not just tricky but toxic. The main ingredient was collodion, a liquid prepared from guncotton (the explosive nitrocellulose) dipped in sulphuric ether and alcohol. “The manufacture of guncotton is usually very difficult and dangerous,” warned N.G. Burgess in his 1863 Photograph Manual. The wet mixture was spread across the face of a glass plate, which took considerable care and time. The glass plate was inserted into a lightproof frame, and rushed out to a camera waiting on a tripod. The lens was opened for a number of seconds, and the plate was rushed back into the dark tent to be developed in a bath of yet another tricky chemical. From there it was sent to Washington or New York for printing, where photographers had to go onto the roof of the studio to find enough light to complete the process. “If the weather was cloudy for weeks, you couldn’t make any prints,” says Sandweiss.

Gardner’s team shot the battles of Gettysburg and Fredericksburg and the siege of Petersburg, but because of the lengthy time required to expose the images, we have no “action shots” of Civil War battles. Many of the photos were posed shots taken before or after battle, of fortifications and bridges, of officers and their horses, of men working or relaxing in camp, and of bodies.

Gardner’s text left no doubt where his sympathies lay. In his captions, the Union soldiers are always “our” troops, and the treasonous Southerners rebels with a lower-case “r.” We have very few photographs taken by photographers from the South, because the Union blockade denied them materials.

The war forced photographers to become more adventurous. Says Sandweiss: “I think it’s fair to say that some of those photographers learned from the Civil War experience about photographing in difficult field conditions, in heat and cold, learning to cope with the cranky technology, and many of them later took their hard-won expertise west, as photographers on the great postwar surveys.”

After the war Gardner continued making pictures of important subjects. He took photos of the execution of Lincoln’s assassins, served as field photographer for the Union Pacific Railroad in Texas and Kansas, and was present, with his camera, for negotiations between the federal government and Indian tribes. He died in 1882; his old boss, Brady, went bankrupt and died in the charity ward of a New York hospital in 1896.

There was no doubt in Gardner’s mind about the importance of the photographic record he’d helped make. “As mementos of the fearful struggle through which the country has just passed,” he wrote in his introduction to the Sketch Book, “it is confidently hoped that it will possess an enduring interest.”

Freelance writer Merrell Noden ’78 is a frequent PAW contributor.

1 Response

Frank E. Bell III ’68

10 Years AgoCivil War Photos

As a Master Ranger Corps volunteer at Antietam National Battlefield, I was delighted to learn that Princeton’s collections encompass one of the few copies of Alexander Gardner’s Sketch Book, plus photographs contributed by Gen. George McClellan’s namesake and only son (feature, March 19). Mathew Brady’s New York exhibit of the extraordinary Antietam images taken by Gardner (and James F. Gibson) is arguably where modern photojournalism began.

One correction to this fine article: The battlefield is 64 miles (not 25) from Washington, D.C., as a quick check with Professor Emeritus James McPherson, a welcome and frequent visitor to Sharpsburg, Md., would have revealed.