Who's Bill? How hot dogs and Esther Williams flicks became tools of foreign policy

I used to teach Princeton undergraduates about the Middle East, including many who were curious about having a career in public service. I shared their curiosity and left Princeton to work in government — one of the most consequential experiences of my life. Now, back in academia, I am writing a book about President Eisenhower and the Middle East, and in my research, I learned about the exploits of a young Princeton graduate, William Lakeland ’44, who found himself at the center of action on the international stage when he was barely 30. I obtained an oral history from Lakeland in April; his story is as remarkable as it is unknown — and an example for students of just how rewarding an enterprising career in public service can be.

In May 1953, John Foster Dulles 1908 arrived in Cairo, the first stop on a tour of the Middle East. He was the first serving secretary of state to visit Egypt, which was becoming a strategic prize in the Cold War.

If Egypt was the key to the Middle East, Gamal Abd al-Nasser was the key to Egypt. The charismatic young colonel had led the military coup that toppled King Farouk one year earlier. Dulles was anxious to take the measure of the man. He huddled together with Nasser in a room crowded with Egyptian and American advisers. During their discussion, Nasser kept drawing Dulles’ attention to conversations that he had been having with “Bill,” whom he did not identify further. Eventually Dulles had to interject: “Who’s Bill?”

Bill Lakeland, a junior political officer in the embassy in Cairo, was in the room, standing with his back against the wall, more a spectator than a participant. In response to Dulles’ question, he raised his hand sheepishly to identify himself. With an awkward glance, Dulles dismissively acknowledged him.

To Dulles, Lakeland was a faceless staffer. To Nasser, he was a trusted confidant and the primary link to the American embassy. For the better part of a year, the new leaders of Egypt had been regular guests at the Lakelands’ apartment overlooking the Nile. Bill and his wife, Mary Jo, held informal dinners for Nasser at least twice a month, sometimes screening American movies on the wall with a projector. (Esther Williams was a favorite of Nasser’s.) Lakeland’s breezy familiarity with the most powerful man in Egypt was unthinkable for someone of such a junior rank. The Egyptians delighted in ribbing him with “Who’s Bill?” — reminding him that he was unknown to his own secretary of state.

In recent years, the question “Who’s Bill?” has come up again. Thanks to the opening of American and British archives from the period, cryptic references to Lakeland’s unique friendship with Nasser have found their way into the history books.

Lakeland graduated from Princeton a year early to join the Marines. He fought in the Pacific, losing an eye. While in the hospital recovering from his wounds, he decided to join the State Department. By 1951 he had a couple of overseas assignments under his belt, and he had undergone Arabic language training. He then was offered the position of second political officer in Cairo. As luck would have it, the first political officer’s post also was opening up just when Lakeland arrived in Egypt. It would remain vacant for several months. As a result, the outgoing officer transferred his Egyptian contacts solely to Lakeland, who cultivated them himself — for a time, at least.

And what a time it was. The country was on the verge of revolution. In addition, Egypt and Britain stood on the brink of war. A British garrison of some 80,000 men was occupying the Suez Canal Zone against the will of the Egyptian government. Guerilla attacks against the British took place regularly. The Americans felt caught between their British allies and the Egyptians, whom they hoped to develop as a bulwark against the Soviet Union in the Middle East. The power of the United States was at its apogee. It was a good moment to be an American official looking for friends.

Lakeland’s best contact was a newspaper reporter of his own age, Mohamed Hassanein Heikal. In 1951, he was still obscure, but in just a few years, Heikal would become the most famous journalist in the Arab world, thanks to his close relationship with Nasser. He passed clues to Lakeland that a coup was in the making — for example, pointing to the surprising outcome of a 1951 election for the presidency of the officers’ club in Cairo. Traditionally, the palace candidate would win hands down, but this time an opposition candidate — Brig. Gen. Mohammed Neguib — defeated the king’s chosen man.

The American ambassador, Jefferson Caffery, was intrigued with the information about a coup that Lakeland was unearthing, but was not willing to report it to Washington as authoritative, for fear of appearing to pass on unfounded rumors. Then, at 2 a.m. on July 23, 1952, the embassy received the first reports that a coup was under way. Lakeland’s superiors, including the ambassador, had followed the Egyptian political elite to Alexandria, on the coast, to escape Cairo’s sweltering heat. Lakeland, the junior officer, was left behind in the city, where the real action was taking place. As soon as he realized that a coup had begun, he called Heikal’s office. The operator already had Heikal on another line — he was out in the city following the unfolding of the coup — and patched Lakeland through. “Things are moving, Bill,” Heikal said excitedly. “Things are moving. I can’t talk now.”

Before long, however, Heikal did start talking. He showed Lakeland a photograph of officers in a newspaper and, pointing to Nasser, said, “This is the man to watch,” indicating to Lakeland that Neguib was just the front man of the revolutionary movement, not its true leader.

Soon, Lakeland became the glue between the American embassy and the new leadership in Egypt. Heikal found a novel way to bring Lakeland and Nasser together. While touring the United States as a guest of the government, the Egyptian reporter had developed a taste for American fast food. “Nasser and the boys wouldn’t mind having some hot dogs,” Heikal told Lakeland, who immediately issued what would become the first of many dinner invitations.

Ambassador Caffery, who held considerable sway in Washington, encouraged Lakeland to develop his unorthodox relationship with Nasser and to make good use of it. The British, however, were livid. They craved American support in their conflict with Egypt, and they believed that Lakeland’s coziness with Nasser was tilting the United States in the wrong direction. British diplomatic dispatches derided Lakeland as “more Egyptian than the Egyptians.” They complained that he was “notable for his youthful enthusiasm and idealistic, even sentimental, approach to the Egyptians, untempered by realism and uncoloured by any feeling of solidarity with us.” Lakeland, they claimed, gave Nasser and his colleagues the impression that they “could get what they wanted if they pushed the British a little further still.” The British railed even more bitterly against Caffery, but the American documents make it clear that their problem actually started at the top — with President Eisenhower and Dulles, who had decided to back the key Egyptian demand of ending the British occupation. Dulles might not have known Lakeland by name, but he realized that the embassy had a special relationship with the Egyptians, and he supported it.

Lakeland did have detractors in the State Department, however. After one visit to Cairo, Parker T. Hart, the assistant secretary of state for the Middle East, complained that Lakeland had become “a very thin line” to the “small gang” around Nasser. There was “something 19th-century about this kind of diplomatic contact,” which was “not the stuff out of which modern international relations are made,” Hart said.

And Lakeland’s access to Nasser aroused the jealousy of the CIA. Even as Hart was thinking about changing the way that the State Department did business with Nasser, the CIA was muscling in on the diplomats’ turf. For years it has been well known that the CIA played a significant role in managing the relationship with Nasser. Some accounts go so far as to suggest that the CIA helped Nasser topple King Farouk and that Lakeland was a spy, but the record shows that the CIA’s close relationship with Nasser developed after the coup. Those rumors that Lakeland was a spy? “Absolutely untrue,” he says. “I was a regular Foreign Service officer.”

As the CIA took more control, Lakeland began to notice that he was out of the loop on some issues of substance: “I rather resented the use of this sort of spooky channel by some of the secretaries of state, including Mr. Dulles, whose own brother [Allen Dulles 1914], of course, ran the CIA and who was quite prone to use the CIA as a convenient way of back-channel operations and communication.”

Lakeland and Caffery left Cairo in late 1954. In October, an American-brokered agreement over the Suez Canal Zone brought the British occupation to an end. In retrospect, the signing of the agreement marked the high point of the relationship with Nasser; by early 1955, tensions were pulling the Egyptians and the Americans apart. Never again would Nasser pop over for hot dogs at the home of an American diplomat.

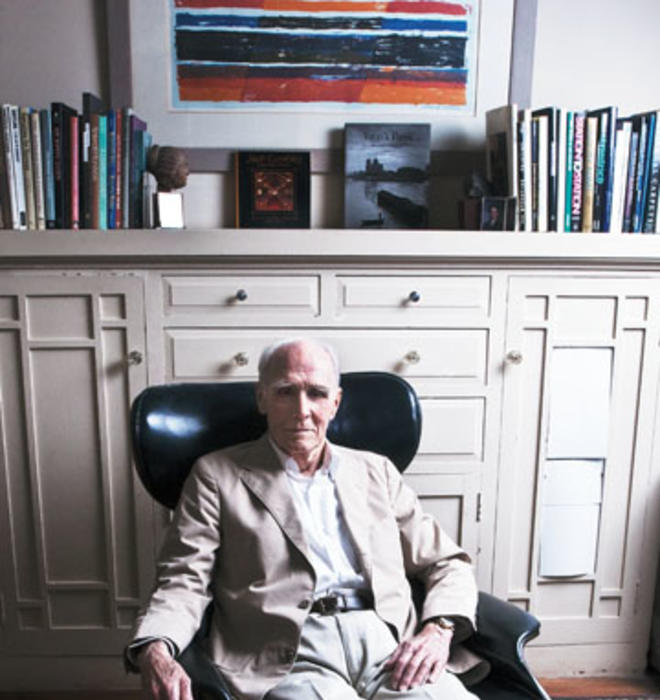

Bill Lakeland is alive and well at 87, and eager to illuminate this fateful period. His interview is available at Mudd Library — which also has the papers of the Dulles brothers — so that no one again will need to ask, “Who’s Bill?’

Michael Doran *97 teaches at New York University and was the National Security Council’s senior director for Near Eastern and North African Affairs.

No responses yet