Photographs by Ricardo Barros and Beverly Schaefer

At her first 11 Commencement ceremonies as president, Shirley Tilghman conferred honorary degrees on some of the world’s most accomplished people. She did that for the last time at her 12th — and also saw the other side of that experience, when the trustees surprised her with her own degree, as a doctor of laws.

“For 12 transformative years, she has led this University with exceptional integrity, humanity, and courage,” trustee David Offensend ’75 read from the citation. “Passionate scientist, teacher, and champion of the arts, she has blazed new paths of discovery, learning, expression, and service; she has widened the doors of opportunity in the name of equity and excellence; and she has strengthened Princeton’s presence throughout the world. ... She has been the personification of Tiger spirit, aiming always, with determination and grace, to live up to her own admonition to aim high and be bold,” a direction Tilghman has given to each graduating class.

The honor inspired a standing ovation, but the outgoing president — who ended her term June 30 — didn’t have much time to soak in the applause: Immediately after receiving her degree, she launched into her final presidential address, celebrating how the Class of 2013 had left its mark on Princeton — from performing dances and creating new companies to racking up a Big Three football title, assuring a bonfire. Tilghman also put in a plug for the value of a liberal-arts education: “Despite the slings and arrows directed at it by those who favor a more utilitarian approach, a liberal-arts education is a great privilege,” she said. But with that privilege, she continued, “comes an obligation to pursue a life with a purpose that is larger than you.”

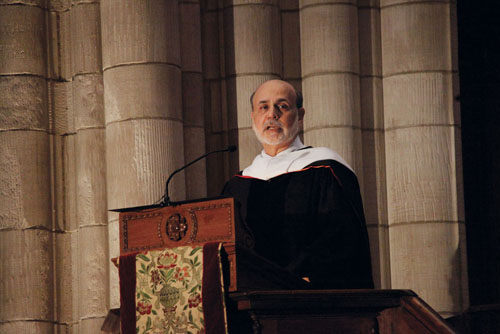

Because Princeton reserves its Commencement speech for the president, guest speakers make their remarks at other graduation events. On the Sunday between Reunions and Commencement, the seniors processed into the Chapel, in caps and gowns, to hear Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke, a former chairman of Princeton’s economics department, address them at Baccalaureate. He offered 10 tips for life after Princeton, leading the list with an admonition to let unplanned opportunities play out. “Life is amazingly unpredictable,” he said. “Any 22-year-old who thinks he or she knows where they will be in 10 years, much less in 30, is simply lacking imagination.”

The next day was Class Day, a time known for clowning around. This year, Class Day included both laughs and thoughtful reflection. On the lighter side, student speaker Dan Abromowitz ’13 apologized to New Yorker editor David Remnick ’81, the keynote speaker, because Abromowitz’s father, David Abromowitz ’78, helped “hose” Remnick from the Press Club the first time he applied. “If you would like to fight my dad, I would strongly encourage that,” he said. “He’s the bald guy who’s mad at me.” Remnick declined, noting it was punishment enough that the senior Abromowitz saw that Remnick has “reunion hair.”

Remnick also poked fun at Harvard for its “gut courses like ‘Introduction to Congress’” (the course was the center of a cheating scandal early last year) and recalled how his mother expressed her disappointment at his choice of a major by announcing “that I would now surely be able to open a comparative-literature store.”

But once he had hooked the students with humor, Remnick delivered a more serious message — like Tilghman’s the following day, a message of obligation. With the good fortune of a Princeton education, he said, comes responsibility to help build a free society. “Freedom is rare, fragile, and provisional,” said Remnick, who recalled his experience as a newspaper correspondent in Moscow as the Soviet Union and communism were collapsing. At the time, he said, he believed that democracy had been born — an optimism that proved “outsized and premature.”

“No doubt, many of you entertained similar hopes as you watched the events two years ago in Tahrir Square, in Cairo,” he said. “Or in Tunis. Or in the first days of the anti-Assad demonstrations in Damascus. Your parents certainly remember the televised scenes, in 1989, of Tiananmen Square — young student leaders no older than you, brandishing democratic slogans in the face of Chinese communist police — and tanks, eventually. In those moments of historical delirium, if you squinted just so, liberty was within reach. The lock of history had been tripped.

“But mentalities, repressive institutions, and history don’t change so smoothly or so easily,” Remnick continued. The Chinese communist government remains in power; Russia is headed by authoritarian Vladimir Putin; Egypt’s ruling Muslim Brotherhood “mocks the pluralistic tone of those first street protests on Tahrir Square.”

There are many ways in which people are not free, he said, and graduates have a role to play in all of them. “It includes the system designer at a social-media conglomerate who might determine to what extent privacy is just something to relinquish and commodify,” he said. “It includes the scientists and managers of our pharmaceutical industry — they’ll help determine not only what future therapies are available, but who can receive them, and on what terms. It includes writers and artists, scholars and policymakers, who help establish and preserve a sense of what society actually cares about. It includes people in finance who have it in them to decide whether their immense economic power extends to the public good or not, to real governance and scrutiny and generosity or not. In other words, there is no life of freedom without some sense of community responsibility.”

Seniors interviewed after Remnick’s speech called it inspiring. His message resonated in particular with Gavi Barnhard ’13, who will study Arabic in Egypt and later hopes to work for the State Department. Remnick’s admonition to pursue freedom is “definitely something that spoke to me. It’s something I feel echoes my entire Princeton education in some way,” Barnhard said. Kevin Ofori ’13 added, “It called us to really think about what we’re doing and be mindful of how we can actually use our education to do what it’s supposed to do, which is to change things.”

No responses yet