LOOK FOR HIM HERE.

Begin at the house in Laguna Beach, Calif., at the end of a steep, winding driveway. Across the tops of the palm trees, it offers a breathtaking view of the Pacific Ocean on one side and Aliso Canyon on the other.

Richard Halliburton 1921 called it Hangover House, a double entendre suggesting both its location high above the beach and the parties held there. A modernist masterpiece of concrete, steel, and glass, it was the inspiration for the Heller house in Ayn Rand’s novel The Fountainhead. Halliburton built it in 1938 for $36,000, a lot of money during the Depression, but affordable for a man who was one of the best-selling travel writers in the world. In recent years, it has been on and off the market; now it appears to be unoccupied. On a recent visit, all the shades were drawn and one large glass panel in the front window was missing.

Getting close enough to investigate is risky. A sign at the foot of the driveway, next to the rusted mailbox, warns, “No Trespassing.” This presents the visitor with a choice: Heed the warning or go up? What would Richard Halliburton have done?

That’s easy. Halliburton certainly would have gone up. What others called trespassing, or recklessness, or foolishness, he called adventure, and the siren of faraway places sang to him throughout his life. That is why he once hid in the Taj Mahal after closing time to swim in its reflecting pools by moonlight. Why he was arrested on Gibraltar on suspicion of being a German spy. Why he once hired an elephant to retrace Hannibal’s route over the Alps and a ship to re-create Odysseus’ voyage around the Mediterranean. Why he defied alligators to swim the Panama Canal.

And it is why he drowned at sea 80 years ago, on March 24, 1939, trying to sail a Chinese junk from Hong Kong to San Francisco.

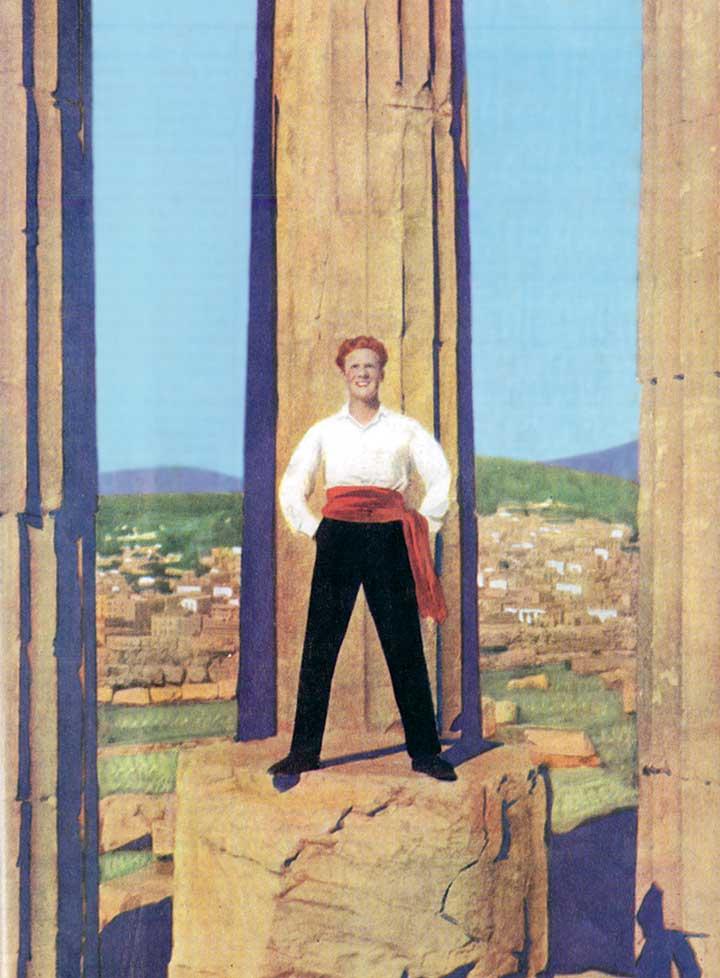

Halliburton chronicled his adventures (highly embellished, some claimed) in eight books, including his most famous one, The Royal Road to Romance. Highbrows dismissed him as a dilettante and his audience as garden-club housewives, but he sold millions, lectured to packed houses around the country, and was billed as “the World’s Most Popular Non-Fiction Writer.” He practically invented the modern travel-adventure genre.

Had he lived, Hangover House would have been his refuge, a place where he could finally stop wandering and settle down with his partner, Paul Mooney. Now his books are out of print, and his house, it seems, sits empty, almost as neglected as Halliburton’s memory.

LOOK FOR HIM HERE.

Number 41 Patton-Wright Hall looks over Elm Drive in three directions. Halliburton lived there for his senior year, one of the last settled periods of his life. He was raised in Memphis, Tenn., the son of a real-estate developer. At Princeton, he majored in English, wrote for the Princetonian, and edited its weekly pictorial supplement. With admirable foresight, his classmates voted him “most original,” but he was standoffish and a loner by temperament. His only close friends were his roommates — Irvine Hockaday, John Henry Leh, Edward Keyes, and James Seiberling — to whom he later dedicated The Royal Road to Romance. “I loved all four of them to death,” he told his publisher. “They were the only one-and-inseparable-now-and-forever type of friends I’d ever had or ever hope to have the rest of my life, but the stamp of correct, standardized propriety which they followed and which I abominated prevented my ever winning their complete approval as a roommate.”

Halliburton spent the fall semester of his junior year abroad, but not the way a student would do it today. During the summer of 1919, he went to New Orleans on the pretext of visiting some friends and, without his parents’ permission, got a job as a mate on a ship bound for England. After crossing the Atlantic, he spent half a year roaming the British and French countryside, crossing the Channel in an open biplane, before returning to Princeton in February 1920.

He tried often to explain why he traveled. As a freshman, he wrote his parents, “Something keeps saying faster, faster — move!” In Royal Road, he distilled it into a philosophy — “try everything once” — which he followed throughout his career. “I wanted to realize my youth while I had it,” he wrote, “and yield to temptation before increasing years and responsibilities robbed me of the courage.”

LOOK FOR HIM HERE.

The Richard Halliburton papers fill 61 boxes in Firestone Library. They contain photographs, publishing contracts, manuscripts, and telegrams announcing innumerable departures and arrivals. The real treasures, though, are nearly 1,000 of his letters home, dashed off on hotel stationery.

Like generations of Princeton students before and since, Halliburton and his roommate Irvine Hockaday decided to see Europe after graduation. So, in the summer of 1921, the pair got jobs on a freighter and worked their way across the Atlantic. Eventually they made their way to Switzerland, where they hired a guide who helped them climb the Matterhorn with only rudimentary equipment. “Crouching on the supreme ledge of snow we ate our breakfast,” he wrote about reaching the top, “with the wind trying to tear us to pieces for presuming to enter her private domain. Savage as they were, we forgot the aroused elements in our exultation over the humiliation of the Matterhorn.”

After that, Hockaday returned to the United States, but Halliburton ventured on. “My trip is my occupation in life,” he wrote to his parents. “I’ve ‘gone to work.’”

Over the next 18 months, he circled the world, weaving his way through Europe, the Middle East, India, and Southeast Asia, traveling as cheaply as he could and supporting himself by selling accounts of his adventures to newspapers and magazines back home. He always provided good material. Weeks before his after-hours swim at the Taj Mahal, he spent a night atop one of the Pyramids. “The droves of annoying tourists had gone to bed ... , ” he wrote with satisfaction in his book. “Five-thousand-year-old Kheops was mine alone.” Later, he crossed the Khyber Pass into Afghanistan, encountered pirates off Macau, and scaled Mount Fuji in January, on his 23rd birthday. “[H]ere,” he recounted, “was a chance to celebrate it by dashing to pieces the age-old tradition that Fuji could never be climbed in winter single-handed.”

These and other exploits formed Halliburton’s first book, The Royal Road to Romance. Published in 1925, it was a best-seller for three years and was published in 15 languages. Reviewers in the serious journals seemed unsure what to make of the young author. “Say what one may,” the Saturday Review of Literature concluded, “his period of travel was a period of emotional inebriation.”

His readers demanded more adventures, so Halliburton began to crank them out. In 1927, he published his second book, The Glorious Adventure, which included accounts of ascending Mount Olympus and attempting to follow the journey of Odysseus. He tried — and failed — to swim the Strait of Messina, where Homer placed the mythical sea monsters Scylla and Charybdis, but succeeded in matching Lord Byron’s swim across the Hellespont, whipping up publicity by having a friend plant a story in The New York Times that he had drowned.

For his next book, New Worlds to Conquer, he retraced Cortez’s route through Mexico, bribed French prison officials to let him spend more than a week living among the convicts on Devil’s Island, and pulled off perhaps his most famous stunt, swimming the entire 51-mile length of the Panama Canal in nine days. At the end, he paid a 36-cent toll, the smallest the canal has ever charged. “SWAM CANAL NINE DAYS EASILY PLEASANTLY,” his telegram home read.

Hard as it was, Halliburton kept trying to top himself. For The Flying Carpet (1932), he hired a pilot to fly him in an open biplane across the Sahara, Northern Africa, the Middle East, India, and the Philippines. As his plane passed over Nepal, Halliburton stood up in the cockpit and took the first aerial photograph of Mount Everest. In 1935, for Seven League Boots, he rented an elephant, which he named Miss Dalrymple, from a Paris zoo; took it by train to Italy; and rode it for a few miles into the Alps to simulate Hannibal’s invasion route.

READ MORE

On the Trail of Richard HalliburtonFrom the PAW Archives: May 1975

At his peak, he was producing a new book — always a best-seller — every year and a half and delivering 50 lectures a month when he was home, often wearing a large turquoise ring he claimed had been given to him by a Tibetan monk training to become the next Buddha. Some doubted that he had actually done all that he claimed or scorned his adventures as sophomoric stunts. When Halliburton sent an inscribed copy of The Glorious Adventure to F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917, Fitzgerald acidly wrote back, “I hope this will reach you before you disappear into Brooklyn to imagine and write another travel book — because don’t think I really believe you’ve been in all these places and done all these things like you say.”

Many critics were not much kinder. “Richard Halliburton,” Vanity Fair chortled, “has made a glorious racket out of Dauntless Youth ... his books are marvelously readable, transparently bogus, extremely popular, and have made their author a millionaire.” Still, if the details weren’t always precisely accurate, wasn’t it the spirit behind them that really mattered?

Moving in celebrity circles, he counted Errol Flynn, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and Charlie Chaplin as friends. Of medium height (5 feet 9 inches) and build (140 pounds), with thick brown hair and blue eyes, Halliburton looked like a movie star. Press agents dubbed him Daring Dick or Romantic Richard.

Though Halliburton was gay, he kept his sexual orientation a closely guarded secret. He met Mooney, a freelance journalist, in 1930 and hired him as his secretary, but biographers agree their relationship was romantic. He soon informed his parents, who did not approve, that henceforward he would not stay at their home during visits but would share an apartment nearby with Mooney.

Heterosexuality was not Halliburton’s only façade. The pace of his nomadic life, lived out of sleeper cars and hotel rooms, began to wear on him. During one of his first trips he had written that he felt “doomed to seek, seek all my life, never content with what I have, despising it after I have it, seeking a higher place and greater fame every step upward.” Often, it seemed, the road he traveled was not in search of romance, but of something else he could never quite name.

LOOK FOR HIM HERE.

The carillon in the Richard Halliburton Memorial Tower tolls the hours on the campus of Rhodes College in Memphis. His father, a longtime friend of the college president, donated the tower in 1962.

As much a creature of the Jazz Age as flagpole sitters and English Channel swimmers, Halliburton was nearly wiped out in the stock-market crash. His book sales also slumped as the Depression deepened and the posture of “Dauntless Youth” slipped out of fashion, making it all the more important to find new adventures to keep his audience.

He also needed money for the house he was having built for himself and Mooney in Laguna Beach. There were inevitable cost overruns, but Halliburton sounded serene. “I agree with [Dad],” he wrote to his mother, “that once I’m on my mountain-top house I’ll be able to adjust my life onto a calmer plane and grow in spirit rather than in mileage. If I can’t get near the eternal in that house, then it’s not in me.”

Halliburton conceived a plan to sail a Chinese junk from Hong Kong to San Francisco, arriving for the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition. In addition to the book he planned to write about the voyage across the Pacific, he ginned up publicity (and raised money) by selling subscriptions to a newsletter so his fans could follow his preparations.

The project was plagued by delays and difficulties, not the least of which was the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. “If any one of my readers wishes to be driven rapidly and violently insane,” he wrote in one of his newsletters, “let me make a suggestion: Try building a Chinese junk in a Chinese shipyard during a war with Japan.” General Motors backed out of a sponsorship deal, unwilling to have its name associated with something called a “junk.”

The diesel- and sail-powered ship was 75 feet long, with an exaggerated poop deck that made it unstable in rough seas. Halliburton was more obsessed with the decoration; he had it painted with fire-breathing dragons on both sides and the ship’s name, Sea Dragon, on the stern in 3-foot gilded Chinese characters.

Setting off from Hong Kong on Feb. 5, the Sea Dragon was forced to turn back after only five days at sea because of bad weather, illness, and leaks in the hull. Halliburton tried to have the leaks patched and the keel extended to increase stability. In his last letter, he wrote to his parents, “So good bye again. ... Think of it as wonderful sport, and not as something hazardous and foolish. I embrace you all.”

With a crew of 15, including Halliburton and Mooney, the Sea Dragon sailed out of Hong Kong for the second time on March 3. Three weeks at sea, they encountered a typhoon, with tremendous winds and 50-foot waves. On the night of March 23, 1939, about 2,400 miles west of Midway Island, the Sea Dragon sent a final radio message, which bore the captain’s name but sounds like Halliburton: “Southerly gales. Rain squalls. Lee rail under water. Hardtack. Bully beef. Wet bunks. Having wonderful time. Wish you were here instead of me.”

When other ships in the vicinity could not contact the Sea Dragon the following day, they sounded an alarm. Perhaps suspecting that Halliburton’s disappearance was another publicity stunt, the Coast Guard station in Honolulu did not send a rescue ship. More than a month later, the Navy finally spent six days combing an area of the Pacific roughly the size of France before calling off the search.

A year after their son’s disappearance, Halliburton’s parents published his correspondence, excising any mention of Mooney and other men with whom their son might have been romantically involved. At Forest Hill Cemetery, a few miles from Rhodes College and Halliburton’s boyhood home, the family plot is easy to find, marked by four Doric columns. Beside the headstones of his parents and younger brother, a cenotaph — the marker placed on an empty grave — reads:

RICHARD HALLIBURTON

1900–1939

LOST AT SEA

WHERE DOES AN ODYSSEY ULTIMATELY TAKE US, IF NOT BACK HOME?

Return, then, to where we started, to Hangover House, negotiating the hairpin turns down Ceanothus Drive and across the Pacific Coast Highway to the beach. Halliburton’s white elephant broods back up in the hills, but go down to the shoreline, shed shoes and socks, and wade into the water.

Six years after his disappearance, a 30-foot piece of a Chinese junk washed ashore near San Diego. With that possible exception, no trace of Halliburton’s ship or its crew has ever been found. Halliburton disappeared 10 months after Amelia Earhart and in the same general quarter of the Pacific. There were reported Earhart sightings for years after her disappearance, but Halliburton’s name soon slipped from the headlines, though he has been the subject of at least five biographies.

Hardly anyone reads Richard Halliburton anymore, and to modern tastes his books seem breathless and treacly, confirming the literati’s reviews in his own time. Ernest Hemingway, who knew something about travel writing, once dismissed him as the “deceased Ladies Home Journal adventurer.” Generations of fans, however, including Walter Cronkite, Lenny Bruce, Vince Lombardi, and R.W. Apple ’57, adored him. As a 7-year-old, Susan Sontag, a literati’s literati, read Richard Halliburton’s Complete Book of Marvels and was inspired to become a writer. “Halliburton’s books,” she recalled, “informed me that the world contained many wonderful things.”

Maybe the place to look for him, then, is here, knee-deep in the Pacific surf, peering at the sunlight glinting off the blue waves. After all these years, what are we really looking for? Marvels? Glorious adventure? New worlds to conquer? A royal road to romance?

They might all be out there, just over the horizon. Wouldn’t it be thrilling to find out?

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.