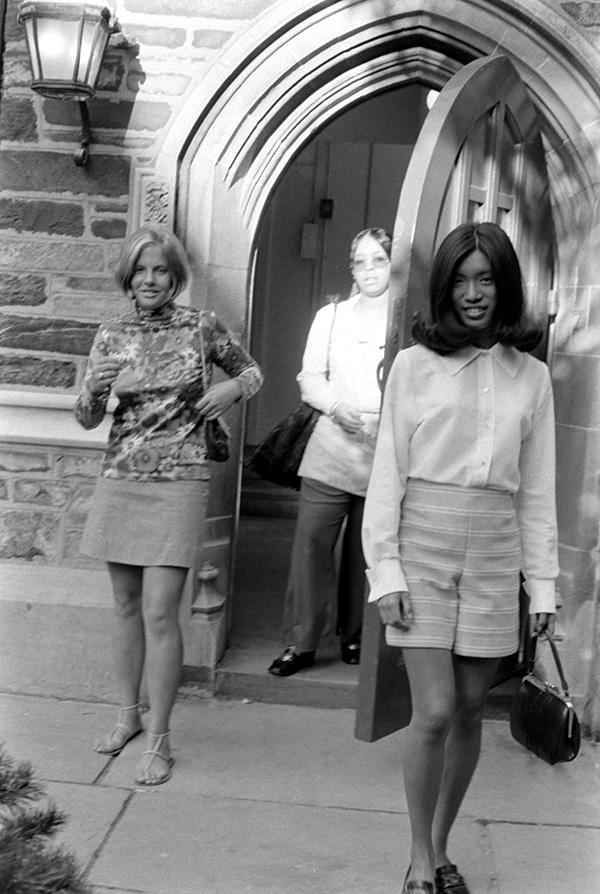

They arrived on Princeton’s campus amid a media circus and graduated four years later at a Commencement marked by political protest.

During their undergraduate years, they discovered intellectual passions, embraced activism, and formed enduring friendships — and they weathered discrimination, harassment, and sexual violence. They felt isolated and unmoored — and they found inner reserves of grit and resilience. They developed a feminist consciousness — and they worried about their dating lives.

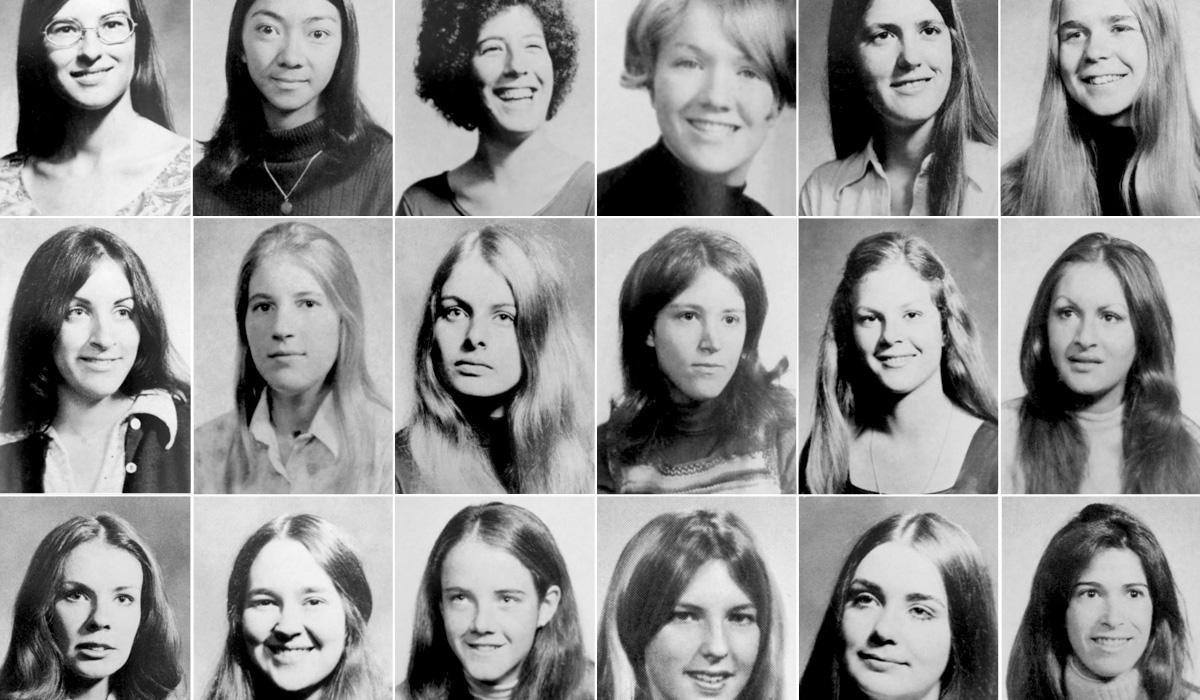

Fifty years ago this June, the University graduated a class that included a small but significant cohort: the first women to spend all four undergraduate years at Princeton. Of the 101 women pictured in the Class of 1973’s Freshman Herald — a smattering of carefully coifed Barbaras, Susans, and Elizabeths in a sea of necktie-wearing Williams, Roberts, and Davids — 81 collected their diplomas four years later. The rest finished in other years or left without earning a Princeton degree.

In recent conversations with PAW, 20 women from that first four-year cohort of 81 — roughly a quarter of the 77 who are still alive — reflected on how the University changed them, and how they changed the University. In the decades after Princeton, they forged careers in such traditionally male-dominated professions as law, medicine, journalism, business, academia, and ministry. They married and divorced, crisscrossed the country and traveled the globe, raised children and welcomed grandchildren. Some look back on their Princeton years with uncomplicated gratitude and affection; others recall more equivocal, even traumatic, experiences, sometimes shaped as much by race and class as by gender. And even those who did not see themselves as pioneers when they entered Princeton have come to appreciate their groundbreaking role.

“It required a certain energy and drive and curiosity,” says Mara Minerva Melum ’73, an executive coach and consultant who lives in Minnesota. “We had to be people that were willing to take a leap.”

The board of trustees vote that launched coeducation capped nearly two years of careful study and consensus-building. But the final decision, made on April 19, 1969, committed the University to a rushed implementation timetable: Princeton would greet its first female freshmen less than five months later. (Not coincidentally, the timing ensured that Princeton would enroll women at the same time as Yale, which had already announced its own coeducation initiative.) So uncertain had Princeton’s plans been that the University did not start accepting applications from women until February, since it wasn’t clear there would be places for them in September.

Princeton’s first women heard about the University’s deliberations from news reports, alumni fathers, guidance counselors, friends. Marsha Levy-Warren ’73, now a clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst in New York City, got her application from the girl sitting in front of her in Latin class. Tonna Gibert ’73, now a writer, copy editor, and African Methodist Episcopal minister in Memphis, knew from the first that she would be accepted: Princeton had phoned her Illinois high school in search of high-achieving young Black women to admit.

Some of the women chose Princeton for the same reasons men did: the University’s prestigious reputation and academic bounty. Others already identified with the burgeoning women’s liberation movement and liked the idea of breaking feminist ground. And still others craved adventure. “It just seemed like somebody handed you a ticket to a really cool ride,” says Melinda Ruderman Boroson ’73, now a retired textbook editor living near Boston. “And it’s like, ‘Yeah, why wouldn’t I take this?’”

“I could tell that some of the professors were really not happy that I was there, and I didn’t know whether it was because I was Black, or whether it was because I was a woman.”

— Tonna Gibert ’73

The women embodied the contradictions of the late ’60s, a moment when traditional conceptions of femininity were beginning to make space for alternatives. In high school, the newly minted Princetonians were yearbook editors, valedictorians, and club presidents; they envisioned careers in medicine or journalism or art history. But the summer before enrolling, June Fletcher ’73 had not only interned at her local newspaper, she had also been crowned Miss Bikini USA in a Jersey Shore beauty pageant. Jan Hill ’73 had earned college scholarship money representing Kentucky in the Betty Crocker Search for the All-American Homemaker of Tomorrow.

Scrambling to prepare for the new arrivals, Princeton hired its first female assistant dean of students, Halcyone “Halcy” Bohen; equipped dorm bedrooms with bolsters and curtains; and installed locks on the doors of the Pyne Hall entryways where all the female students would live. But Princeton had not thought deeply about women’s education. Economics professor Gardner Patterson’s 1968 report on coeducation, which undergirded the University’s decision-making, devoted less than one of its 56 pages to a section headed “Can Princeton Do Justice to Women Students?”

“To the extent that women figured in the conversation, it was mainly in terms of how their presence would be good, or less good, for Princeton University and Princeton men,” former Princeton administrator and history professor Nancy Weiss Malkiel wrote in “Keep the Damned Women Out”: The Struggle for Coeducation, her 2016 book about coeducation at elite universities. “Women and their needs were largely left out of the equation.”

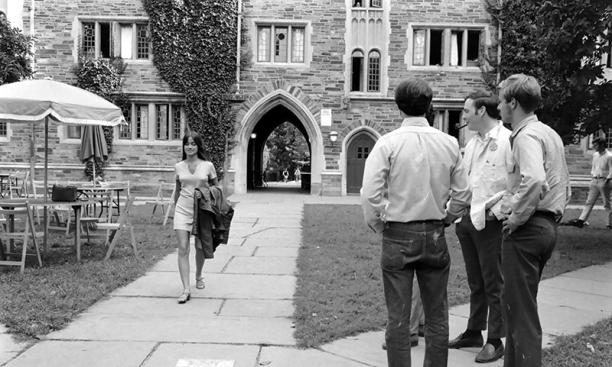

Although the Patterson report had recommended a 3-to-1 male-to-female ratio — alumni had been told the University would not reduce the number of male students to make space for women — the first female cohort arrived on a campus where the numbers were far more skewed. In fall 1969, along with its 101 female freshmen, Princeton enrolled 69 upper-level female undergraduates — 48 transfer students and 21 visiting students attending classes at the University under the grant-funded Critical Languages Program. These 170 undergraduate women took their place amid more than 3,200 undergraduate men, yielding a 19-to-1 male-to-female ratio.

The maleness of the institution asserted itself in ways both symbolic and practical. The faculty included only three female professors, including Weiss Malkiel, and 17 female lecturers. On campus, women’s bathrooms were scarce and women’s locker rooms nonexistent. The alma mater, “Old Nassau,” hailed Princeton’s “sons.” The Princeton Club of New York housed a restaurant known as the Men’s Grill, whose floor plaque proclaimed it a place “where women cease from troubling.”

“I thought, because they had said they were taking women, that it was going to be a coed school,” says Lisa (Dorota) Tebbe ’73, a Connecticut resident, who retired after careers as a business executive and a hospice chaplain. “And it turned out I was going to a man’s school.”

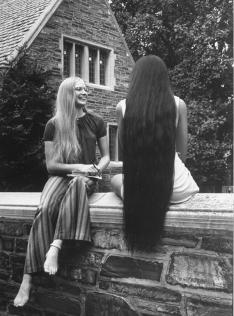

The arrival of Princeton’s first coeds was national news, and for a week in September, the press swarmed Pyne Hall’s courtyard. In her entryway bathroom, Levy-Warren discovered a female reporter perched on a sink, scouting for interviews. Photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt shot pictures for Life magazine; the New York Times’ story mentioned Bohen, the new assistant dean (“a chic 31-year-old mother of three”) and quoted Fletcher (“a statuesque blond”) in a section titled “Miss Bikini Goes to College.”

Even after the press went home, Princeton’s female students felt weirdly conspicuous. “The first couple of weeks, you would catch, out of the corner of your eye, people pointing — ‘There’s one!’” recalls Hill, a retired lawyer who lives in Virginia. When a woman entered the dining hall, male students sometimes “spooned” — banged their utensils noisily on tables or metal pitchers. While some women enjoyed the attention, others found it uncomfortable. One day, a male student mentioned to Karen Rosenberg ’73 that she’d changed her outfit. “I didn’t like that people were watching,” says Rosenberg, now a freelance writer in New Jersey. “We were under the microscope,” says Macie (Green) VanRensselaer ’73, who worked in academic technology and lives in Baltimore. “Everything we did was being examined.”

“I thought, because they had said they were taking women, that it was going to be a coed school. And it turned out I was going to a man’s school.”

—Lisa (Dorota) Tebbe ’73

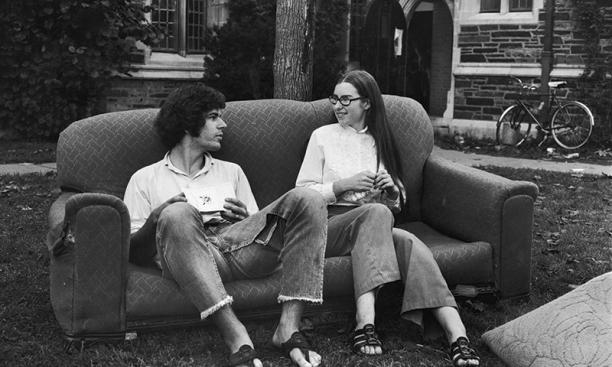

Princeton’s efforts to make its new female students feel less isolated sometimes had the opposite effect, the women found: Rooming them behind locked entryway doors in a single building on the western edge of campus — “the Pyne Hall ghetto,” Jane Leifer ’73 called it in a 1973 essay — seemed restrictive and patronizing.

“I was outraged by it,” Robin Herman ’73, a journalist who died last year, told a Princeton audience in 2011. “What were we — princesses, to be locked up in the tower? We were there to integrate, we were there to be part of the University, and yet they had put a lock on our doors.”

Their social position felt oddly equivocal in other ways, too. Before coeducation, Princeton men spent their weekends road-tripping to women’s colleges or pairing off with visiting out-of-towners. For a year or two after coeducation, these rituals persisted. “There would be these buses that would pull up to the gym, and these beautiful blonde women would descend from the bus, all wearing gold jewelry and camel hair coats,” says S. Georgia Nugent ’73, now president of Illinois Wesleyan University. Male classmates who were friends during the week looked elsewhere for dates once Friday night arrived. “We were like a third sex,” says Lizabeth Cohen ’73, now a Harvard history professor. “There were the men. There were the women that they were used to importing on the weekends. And then there were us.”

Male students seemed to think, erroneously, “that there were men lining up at our door, and they couldn’t possibly compete with all these other guys who were better-looking, smarter, more athletic,” Tebbe says. Those who tried their luck anyway weren’t necessarily prizes. “You met a lot of the jerks, because they were the ones who were pushy enough to meet you,” Rosenberg says. By November, Tebbe stopped dating. The men who asked her out seemed to be “doing it so they could say they had gone out with a coed,” Tebbe says. “I wasn’t a person, I was a trophy.”

Women bonded with fellow residents of Pyne Hall, especially those who shared their entryway bathroom, but small as the female cohort was, few initially felt a strong sense of group solidarity. Paradoxically, that disconnection itself stemmed from the cohort’s size. “Because there were so many more men than women, I was with men more than women,” Melum says. “And so I think it was just almost natural that I wasn’t as close to the women.”

But the world beyond campus was changing rapidly. The year before the women arrived, Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. In December of freshman year, the nation held its first Vietnam-era draft lottery, and the following spring, National Guardsmen killed four students during antiwar protests at Kent State University. In the aftermath, Princeton canceled final exams after students and faculty voted to strike in protest against the invasion of Cambodia.

Amid the turmoil, some of the women experienced a feminist awakening. “Literally within a minute of arriving on the Princeton campus, I would have called myself a feminist,” says Barbara Weinstein ’73, now a history professor at New York University. “I had gone to public high schools where many and maybe even most of the teachers were women. It weighed on me that every time you walked into a classroom, the person speaking with authority was a man.” Her first summer back home, Boroson made time to read The Feminine Mystique.

Like so many students at elite colleges, the women felt intense pressure to achieve. “I was always in fear that they’re going to find out that I don’t really belong here,” says Elaine Chan ’73, the cohort’s sole Asian American woman, who spent her career in government and now lives in Washington state. “I just wanted to work hard and show that I deserve the place that I’ve been given.”

But for Princeton’s first women, their status as gender pioneers compounded ordinary insecurities. “We knew it wasn’t just for us,” says Fletcher, now a retired journalist living in Florida. “We knew if we failed in any way, it could affect the decision of Princeton to continue with its experiment in coeducation.”

Early on, Beth Rom-Rymer ’73 told a psychology professor about her career plans. “And he said, ‘Well, you know, you have to be better than every single man in your class, because you’re not likely going to be accepted unless you’re better than everybody else,’” says Rom-Rymer, now a psychologist in Chicago. “And I said, ‘OK, I’ll do whatever it takes.’

“So I didn’t necessarily see that as sexism,” she adds, “although, of course, it was.”

When economist Patterson surveyed Princeton’s male constituencies for his 1968 report, he found strong support for coeducation among undergraduates and faculty. Even among alumni, his limited sampling uncovered majority opposition only from the oldest, those who had graduated more than 50 years earlier; the youngest alumni overwhelmingly favored coeducation.

For many of the women in the first four-year cohort, Patterson’s findings tallied with their own experiences: They forged strong friendships with male students they met in their classes or eating clubs, and their newfound passions for classics or geology, history or social psychology were encouraged and supported by male faculty. “I loved it,” says Nugent. “I have always described it as if there were suddenly just enormous windows thrown open on the world.”

Still, hostility, discrimination, and sexual harassment were hardly uncommon. More than half the 20 women interviewed by PAW described unsettling, infuriating, or traumatic experiences with alumni, faculty, or fellow students.

An alumnus seated next to Hill at a University function asked how she felt knowing that Princeton had gone coed only to prevent the best male students from choosing Yale. After a press write-up, Melum got several angry letters from alumni insisting that women would ruin Princeton. And the summer after freshman year, not long after speaking to a Chicago-area alumni association, Gibert received an anonymous letter addressing her in racist and misogynist terms and calling her “a bleeding cancer sore on the body of Princeton.” Gibert, who had grown up in a devoutly Christian home, took the letter to her mother, who placed it in her Bible. “I was brought up to pray for those who persecute you,” Gibert says.

In classes that often included only one or two women, faculty behavior could range from clueless to predatory. A chemistry professor told his students he would have to curb his swearing now that a woman — Susan Petty ’73 — was among them; an English preceptor asked Gail Finney ’73 to provide “a feminine perspective” on D.H. Lawrence’s novel Women in Love. “I thought, ‘OK, so I’m supposed to speak for half the human race,’” says Finney, now a retired professor of German and comparative literature at the University of California, Davis. “Of course, all the men in the class, their eyes are on me: She’s going to give us the wisdom of women.”

But some of the faculty joshing was less benign. When Laurie (Watson) Raymond ’73 arrived late for physics, the professor beckoned her over to a telescope trained on the back wall. As her male classmates giggled, Raymond, now a semi-retired psychiatrist living in Kentucky, peered in at a photo of Dolly Parton in a low-cut blouse.

“We were like a third sex. There were the men. There were the women that they were used to importing on the weekends. And then there were us.”

— Lizabeth Cohen ’73

Outright discrimination occurred as well. The men’s crew invited Hill to try out for coxswain, but when she followed up, “I was told by a man in a suit that they were not allowing women in the men’s boathouse,” Hill says. And when Petty tried switching her major from geology to geological engineering, the head of the program refused to allow it. “He said to me, ‘I don’t think women should have gone to Princeton, I don’t think women should be geologists, and I don’t think they should be engineers. And I will stop you from getting into this program, and if you complain and tell people, I’ll make your life a misery,’” Petty recalls.

If some older men seemed angry about the presence of women, others welcomed it rather too enthusiastically. One of Tebbe’s instructors wrote, “Nice perfume!” on her paper; another invited her to spend the weekend with him. A junior faculty member asked Rosenberg to sleep over at his place; a professor for whom Levy-Warren had been babysitting drove her home one night and, before she could leave his car, grabbed her and kissed her.

Many of Princeton’s male students had hailed coeducation — WPRB played Handel’s “Hallelujah” chorus on the day the trustees voted to admit women — but boorish or predatory behavior persisted nonetheless. Fletcher and Petty remember men urinating out of windows as they passed underneath; Raymond ducked a cheesecake tossed out of Blair Arch. The uniform Petty was required to wear to her job in a campus dining hall was too short, so male students placed crates of drinks on the floor, “spooning” when she bent over to retrieve them.

Fletcher, whose Miss Bikini USA title had made The New York Times, attended a University Press Club meeting presided over by someone who may have been an older student. “The adviser to the club said, “‘Well, you know, we don’t want any of these go-go dancers’ — and he makes that hourglass figure with his hands — ‘in our club,’” Fletcher recalls. “And I’m humiliated and red-faced, and I walk out.”

In the spring of her sophomore year, VanRensselaer recalls, she was drugged and raped by a male classmate. Years later, during a late-night Reunions conversation with a half-dozen other women, she learned that all of them had been assaulted as well — by the same man. “I think I and the other women in this group just assumed, ‘Well, it was my fault,’” VanRensselaer says. “There weren’t words for it then.”

Almost everything was harder for the cohort’s few women of color. In a physics class one day, the preceptor commended a particularly interesting written answer, “and when I got up, and the TA realized it was me, his face kind of dropped,” says Celeste (Brickler) Hart ’73, one of six Black women among the original 101. “What are you doing at Princeton?” a TA wrote on Gibert’s philosophy paper.

“I could tell that some of the professors were really not happy that I was there,” Gibert says, “and I didn’t know whether it was because I was Black, or whether it was because I was a woman.” But rather than complain to their families, she and Hart gritted their teeth and got on with it. “It wasn’t anything I wasn’t accustomed to, because I integrated my junior high school,” says Hart, now an endocrinologist in Florida. “There were four Black kids in my class, and you frequently ate lunch alone, got called the N-word in the hall. So it was something that I had learned to put behind me.”

Women from working-class families with little experience of higher education faced their own challenges navigating academia’s unwritten rules: The classics graduate school plans of Nugent, a first-generation college student, were nearly derailed because no one told her until late in her Princeton career that she needed to study Greek as well as Latin.

Others just found the class distinctions intriguing. “To me, the multigenerational Princetonians and their legacy and their attire and their whole way of being was interesting,” says Sara Sill ’73, an artist and retired lawyer in New York, whose immigrant parents lost their education to the Holocaust. “What would it be like to have that feeling that you totally own this place, that this belongs to you? For me, it was a gift — how would it feel if you actually owned it?”

As the four years passed, life improved for Princeton’s first women undergraduates. Tebbe and Fletcher formed relaxed friendships with men from their eating club. Cohen and Weinstein immersed themselves in anti-war organizing. Levy-Warren helped found the Women’s Center and became student government vice president. Chan worked to create the Third World Center. As more and more women arrived, the “Pyne Hall ghetto” disbanded and women moved into dorms across campus. In the second year of coeducation, according to Malkiel’s book, Princeton enrolled 175 female freshmen; the total number of women on campus rose to 400. By the first cohort’s senior year, the 975 women on campus made up 24% of the undergraduate student body — close to the 3-to-1 ratio Patterson had recommended.

As women’s ranks grew, the uncomfortable spotlight on each individual dimmed. “The more women that were on campus, the easier it felt to be a woman on campus,” Weinstein says. “The numbers really mattered.” But Princeton men had changed, too, she says: “They were not coming to a school where they expected to be only around men.”

The night before graduation, Rom-Rymer, an anti-war activist since high school, stayed up making protest placards. The next day, she ostentatiously walked out of the ceremony, along with dozens of fellow graduates outraged at the awarding of an honorary degree to George Shultz ’42, then Nixon’s treasury secretary. The same day in June 1973, undergraduate degrees were conferred on 168 women — their ranks swelled by transfer students, women now made up 18% of the class — and Levy-Warren was celebrated as the first woman to win the Pyne Honor Prize.

By then, many of the women felt grateful for the chance to attend Princeton. “It gave me opportunities and opened doors and created new horizons for me, and friendships and networks and a kind of belonging that I’d never experienced before,” Chan says. “I tear up when I think about it.”

Not everyone has such happy memories. “I lost myself at Princeton,” Gibert says. “Princeton was life-changing for me, but it was life-changing in a very traumatic way.” For others, however, the sexist opposition they encountered proved motivating. After her rebuff by the Princeton engineering professor, Petty graduated as a geology major, earned a graduate engineering degree, and founded a series of geothermal energy companies. “It put steel in my spine,” says Petty. “Instead of decreasing my self-confidence, it increased it, and I just felt like, ‘Look, if I want to do something, I just have to set out and do it. I can’t wait for somebody else to do it for me.’”

As they made their way in a professional world just beginning to open up to women, Princeton’s first four-year cohort drew on skills honed on campus. “It was very, very helpful to have experience of having to speak up in meetings, not letting them speak over you or try to verbally intimidate you,” Fletcher says. “Tough as it was, it was a very, very good education.”

Ten years after graduation, the women of the Class of ’73 gathered for a reunion breakfast at the Princeton home of one of their number — Nugent, then a professor in the University’s classics department. As an undergraduate, Nugent had not seen herself as a feminist groundbreaker, but that day, a new consciousness began to develop. “I think it was kind of the first chance for us to talk together and come to this realization that we were pioneers,” she says.

In the years since, the reunion breakfast has become a tradition, and the bonds among the women of the Class of ’73 have strengthened. Many members of the pioneering cohort have come to take pride in what they accomplished, even when it came at great cost to themselves. In 2019, at the Thrive conference for Black alumni, Gibert looked around and marveled. “There were so many Black people there,” she remembers. “And I said, ‘OK, this is why I went through this: so that these people would be able to do the things they do.’ They knew the Princeton song. They were wearing the Princeton colors.”

In each spring’s P-rade, the Class of ’73 marches with a banner proclaiming, “Coeducation Begins.” The alumni who so vehemently opposed the admission of women have mostly passed on, and nowadays, when the banner appears, “the younger classes respond to it in such a visceral way that I get puffed up with pride about that,” says Anne Smagorinsky ’73, a retired graphic designer who lives in Boston. “The women in my class really said, ‘This college is going to be coeducational — emphasis on the co. We’re going to take our place in the grand tradition of Princeton students and Princeton alums

as equals.’”

In the years since the first cohort arrived on campus, generations of students have come and gone. The presence of female undergraduates has morphed from extraordinary to unremarkable. Women from the first cohort have daughters who are Princeton graduates.

“I love telling people that I was in the first four-year class of women at Princeton,” Weinstein says. “Tell it to younger people, they say, ‘Princeton used to not have women?’”

Deborah yaffe is a freelance writer based in Princeton Junction, New Jersey.

Correction: A previous version of this article misdescribed the group of 69 upper-level female students enrolled at Princeton in the fall of 1969. This group comprised 48 transfer students and 21 visiting students enrolled in the Critical Languages Program.