Darcie Little Badger ’10 Weaves Lipan Apache Storytelling into Novels

‘I’d like readers to take away just this feeling of hope for the future, for their future’

Ghosts and monsters, strong families and a connection to the Earth fill the two young adult novels penned by Darcie Little Badger ’10. Readers also find traditional Lipan Apache storytelling elements that Badger, a member of the Lipan Apache tribe, learned from her family while growing up in Texas. Badger spoke with PAW about her books — Elatsoe and A Snake Falls to Earth — about facing rejection on her path to becoming a writer, and why she wants her young readers to come away feeling hopeful about the future.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT:

Liz Daugherty: Imagine a world where the old stories told by indigenous American people are true. Not just back then, but now. A world full of ghosts, monsters, spirits that can transform from humans to animals, and teenage heroes who find their own power and use it to protect their families. Darcie Little Badger, a member of the Lipan Apache tribe who holds a doctorate in oceanography, earned acclaim in 2020 with her first young adult novel, Elatsoe, a murder mystery about a teen who can raise the ghosts of animals. Her new novel, A Snake Falls to Earth, draws together storylines about a human girl investigating her family’s history in Texas and a cottonmouth snake spirit finding his way through the parallel Reflecting World.

Darcie, thank you so much for speaking with me today.

DARCIE LITTLE BADGER: Oh, I’m just so happy to be here. (laughs)

LD: So you studied geological and geophysical science at Princeton, and then oceanography at Texas A&M for your Ph.D., so what made you decide to become a writer?

But when I went to Princeton as an undergraduate, my original goal was to become a writer and to study writing at Princeton. And this is actually a story that I tell a lot, because I do think it helps especially young writers deal with rejection. I applied to the creative writing certificate program there twice, and got rejected twice. So I reached a point where I realized that I wouldn’t have enough time to do the certificate program and I had to decide if I wanted to continue studying English, or as a sophomore whether I wanted to switch interests, and that was about when I took this introductory oceanography course, and we went to Bermuda to kind of learn what a research scientist does. And during that process, a professor took us to the Sargasso Sea on the open ocean, and I realized that I knew so very little about this environment that made up so much of the planet, and that just fascinated me. So that’s when I switched focus in terms of, you know, my academic studies, and went to geosciences. And I looked at sea level indicators and plankton, and then as a Ph.D. student, I actually studied the transcriptomics of red tide-forming plankton called Karenia brevis.

But through all that, I was still writing in the background because, despite those rejections, I still knew I wanted to be a writer — I just had to do it my own way. I ended up publishing short science fiction fantasy stories in magazines like Strange Horizons, and of course, writing science fiction and fantasy, found myself inspired, oftentimes, by the science that I was studying as a student. So it was actually, I’m grateful that I did get that opportunity to kind of switch focus, because even in fantasy books like Elatsoe and A Snake Falls to Earth, I find myself drawing upon that background of environmental sciences and the ocean and things that I know just from the science side of things.

I did think that, every day I kind of want to learn more about the world because nobody knows everything, and even though now I’m a full time writer, I will never stop trying to learn. So long story short, y’all rejected me. (laughs) But it is something that, I think it’s a good story to tell just because, as a writer, you know, you do have to deal with rejection a lot and not just, like, rejection from programs but writing short stories, oh, you get tons of rejections before you publish something. And trying to get an agent for a book, you get rejections, and it’s important just to have this sense of perseverance, and not let things like that stop you, if you really want to be a writer. And for me, just this other path that I found turned out to be the best for me.

LD: You had another story, I think, about perseverance, and maybe you could tell it, since you just hit on that point, about your father, right?

DLB: Yes. So my debut book was published in September of 2020, and I have to go back in time a little bit and just talk about the impact that my father had on me becoming a writer, because my dad, he was the chair of the writing department at WestConn, and before that, you know, he was getting his Ph.D. in English and then throughout all that, I was a little kid who wanted to be a writer. And he was actually the person who would edit my very early stories, the first book I wrote. I was in first grade. So as you can imagine, there were some grammar issues or some spelling issues, but my dad, who was getting his doctorate, he actually sat down and he edited it for me and explained what the edits in the book meant, and then he went a step farther and he showed me how to submit my book for publication, and I got a really lovely rejection for that. Seriously, they were very supportive. They were like, “Oh, this kid wants to be a writer, we’re going to be nice about this rejection.”

But my father taught me to be proud of that. He actually framed that rejection and said that, “Someday when you’re a writer, you’re going to want to see this and how far you’ve come. And this is something that you should be proud of putting yourself out there.” So he always supported where I wanted to go as a writer, too, because I’m big into science fiction/fantasy, like my mother. My dad, he was into Shakespearean lit. But that didn’t stop him from saying, “Yeah, if you want to write sci-fi-fantasy, do it.”

So when Elatsoe was actually accepted by Levine Querido for publication, that was actually when my family learned that my dad had terminal cancer — in fact it’s mesothelioma, which is cancer caused by exposure to asbestos. So my father, as a young man, to pay his way through college — and as an undergrad, he actually wanted to be a high school teacher of, you know, Spanish and English, so that’s what he wanted to do in college, and in order to pay his way through that, he did several things like construction. He worked at a steel mill. He painted houses. And all of these might have been potential exposures to asbestos, and in fact, we were told that perhaps multiple exposures are what increased his risk. So throughout this, I guess, debut year process, we were actually as a family trying to, you know, support my father as he fought this very terrible cancer.

So before Elatsoe was published, I was asked to be on a podcast, and it was a podcast for writers, and in fact it was for new writers and aspiring — people who wanted advice, in other words. And I went up to my father, because he really is the wisest man that I know, and I asked him, “You know, when you’re working with your students, what do you think they’d want to hear from a podcast like this? What can I talk about that would help them in their journey?” And it was difficult for him to speak at that point. So he took this long pause, and he was thinking about the answer, I could tell. And then he said one word, and that was, “Perseverance.”

And that’s something that I did talk about, and it’s something that I think is important, not just when it comes to writing but just in life in general. I know it’s something that he was — he was a type of man who would — you know, we have a lot of difficulties as a family, but he would always have some much love for us that we did get through these things together. So that actually is something that I, as a personal philosophy of mine, perseverance and hope and it’s something that my father taught me in every aspect of my life. And I’m so grateful for that.

LD: Yeah, I wanted to ask you about the family threads, because both of these novels have very strong threads about family, and I found it interesting because so often, when you see — these are young adult books — and so often when you see stories about teenagers, you see them breaking away from their families and growing on their own. And of course that’s part of being a teenager, but here we have these teenage protagonists who are very close to their parents and grandparents, and Ellie in Elatsoe feels very close to her Six-Great-Grandmother and this family history that stretches back so far seems to give them strength.

So I was wondering, you know, it sounds like from what you just described with your father that that was definitely a part of your experience growing up. Can you tell me a little bit about that and maybe how that translates into these books?

DLB: Yeah, and it is — as a person working primarily in the young adult field when it comes to my novels, something that’s really cool I think about writing for the young adult audience is that these are readers who are entering adulthood really for the first time. They’re going through a lot of new experiences, a lot of new responsibilities for the first time. And so that theme does play a strong role in many books. And oftentimes, that does involve being in some ways separated from that family net that, as children, we depend upon.

But in Elatsoe, actually the parents, Ellie’s parents, because she’s a 17-year-old teenager living in a world very much like ours. Which means that she has to ask permission to drive off and do an investigation at a library. And I wanted her parents not to impede her investigation but in many ways support it, because she is investigating the murder of her cousin. That’s family. And that’s something that her parents, they also care about deeply, too. And in many ways, that’s — I feel like I wouldn’t be at this point in life if I hadn’t had that support from my parents, and as, you know, I am, you know, I’m a gay writer. And just having that support from my parents and my marriage and stuff has just meant so much to me, and I feel that I’m lucky for that.

And so in these books, these characters happen to be like me in that they do have this system that is helping them reach their goals. But also in The Snake Falls to Earth there’s this other thread in that the main character, Nina, who’s the human character, she’s looking into a story that was conveyed to her by her great-great-grandmother. And this story actually has — at first she doesn’t know what it means because it’s in the Lipan language, and that’s not something she speaks fluently. But as she uncovers more about it, she realizes that this story from the past, generations in the past, that’s been passed down, actually affects how her family’s going to survive in the future, and it happens to be in a magical way.

But this was inspired by my own experience, because I am Lipan Apache. My father’s Irish-American, my mother’s Lipan Apache. I’m enrolled in the Lipan Apache tribe. And much of my personal culture was maintained because of the strength of my great-grandmother, my great-great grandfather. People who, during that very dangerous time in our history, during the 1800s, even into the early 1900s, they maintained our culture and passed that down eventually to me, and there actually is this — I call it a prayer. It’s something my great-great grandfather would say every morning, and he spoke it in the Lipan language, and we had this very incredible oral tradition, not just storytelling but knowledge in general. So that prayer was actually passed down through my family and, in my generation, some of the meaning of some of the words had been lost, but the way they sounded, the way they were spoken was maintained so well that we were actually able to put the meaning back into them. So now we know fully what that prayer means, because it was in Lipan and our language has a lot of holes. We are going through the process, as a tribe, of restoring the language.

But that experience of reclaiming what could have been lost and what is very important, culturally and spiritually, just because of that kind of that family chain of passing down that knowledge, I did want to convey that in A Snake Falls to Earth. Of course, I didn’t use our actual ceremonial prayer, instead, inventing this story that Nina’s great-great grandmother told to her. But the concept is pretty much the same.

LD: Can you tell us what the prayer is? Now I’m curious.

DLB: I can say that it involves the sun, and that’s because the sun — you know, something cool is it’s not just Lipan people who have this connection with the sun. But it is our specific version of it. And yeah, it’s something that I’m trying to do every morning when I wake up in the morning which isn’t super common, but I’m trying to get there. Sometimes it’s in the afternoon. It should be in the morning, though. I do try to say this just because, like, I myself, you know, struggle a lot with speaking the language. I know a few phrases, I know a few words. But it’s something, and I’m actively learning, and that does help, you know, kind of also keep me grounded and connected to my culture.

LD: I definitely wanted to ask you about the connection to the Lipan Apache storytelling and traditions because they appear so much in these books, and I was curious about — you talked about the oral tradition, learning this as you were growing up. How did you learn these things, and how are you incorporating them into your books?

DLB: Well, yes. I failed to mentioned that, in addition to reading a lot of picture books when I was young, my mother would tell me Lipan stories, and these are stories that I really — I maybe found a couple of them written down, but most of them aren’t really written down out there because they were told through that oral storytelling tradition. And a lot of them involve fun characters, especially Coyote. She told me a lot of Coyote stories, and they’d go on adventures, and it just inspired my imagination so much hearing these.

So in A Snake Falls to Earth, Oli, this cottonmouth spirit character, a lot of the fantasy world that he lives in, and a lot of structures of his chapters, are inspired by those stories I heard growing up that would involve these animal people with interesting personalities. But even — like in Elatsoe, for Ellie, a lot of the important stories involve her Six-Great-Grandmother and the cool things that she did a long time ago. And in a way, that reflects just the importance of stories in conveying history. Like, my history, but the history of other indigenous peoples. You don’t always find those in the history textbooks. I can’t say I went to high school in Texas and — Texas is part of our homeland. We’re a state-recognized tribe in Texas, and I learned nothing about the Lipan people. But I knew our history just because I’d heard it from my mother and actually other Lipan elders and knowledgeable people who I knew. And that is important.

LD: Absolutely. Well, and I think in your books, it sort of fuses together, because we get, you know, a teenager who’s doing research on her phone, a teenager who’s doing, you know — how am I describing this? It’s sort of blended together. They’re in a world where the old stories are closer. It’s part of the now. And it’s — I’m not doing a great job of describing this, but I think, as I was reading the books, I was thinking — I thought a lot about how worldbuilding is part of so many young adults novels, and adult novels as well, right? But you seem to have something that I think J.R.R. Tolkien did not have, which is a deeper — deeper roots to the world that you’re building. It feels more real. It feels deeper. More of a deeper connection with the spirit. Does that make sense? That’s the feeling that I got as I was reading it. And so it’s interesting. Like, I was wondering if there was anything you could tell us about how you do that, how you bring those threads together in your books?

DLB: For me, a lot of it is writing what I know. And one way that this appears that’s not conscious and yet I guess it is, my stories and my books tend to take place in Texas, and that really is because of this intimate connection with the land and the area that actually extends beyond me, generations before mine. Because my mother — even my father, he was also a Texan — but on my mother’s side, you go back, we can go back as far as we can and we’ve always — you know, we’ve lived here since the Lipan people came down from the north. And in a way, I’m not much of a planner. So I’m not exactly sure how the worldbuilding happens, and all I can do is hope that readers like it and connect to it. But it is easier for me just to write what I’m familiar with, and that includes this cultural foundation that I was brought up in, the stories that I grew up hearing and reading. And the land itself and the people who live here.

Thank you so much for the compliment. I’m glad — as a writer, you never — you never really know how people are going to receive the stuff you create and just kind of hope for the best, and I’m glad that my worldbuilding does connect with at least some readers.

LD: Well it seems to be connecting with a lot of readers. You’ve won a lot of awards now with these books. Yeah. A lot of best book lists, right, most recently the Locus Award. So yeah. You seem to be getting a lot of attention for these, which must be really exciting, right?

DLB: It really is. And what I hope for just publishing this book is that it would find some readers. And just the fact that it’s received this overwhelmingly positive attention, first of all has blown me away.

Like when my editor called me — it’s an interesting story because A Snake Falls to Earth was on the National Book Award long list, and at the time I was in California, West Coast time, and I also slept until like 2 p.m., so my editor called me that afternoon and told me — was like, “Oh, you’re on this really cool long list.” I was like, “Oh, what’s that?” He’s like, “The National Book Award.” I was like, “Whoa, that sounds really neat.” And it turns out that just looking at the other books that were on there, it was just a huge honor. But unfortunately, people had been asking him all day, like, “How did Darcie respond to this, to see her fantasy book up there on that long list?” He had to tell them that I tended to sleep late.

But it’s — I would say that the reception Elatsoe received actually empowered me in some way to really dig into the story of my heart for A Snake Falls to Earth, because it is told in a way that is highly influenced by Lipan Apache storytelling structure. Everything from the chapters from Oli’s perspective that can be almost standalone stories but connect to a larger plot to just the way that there are multiple potential, I guess, endings — it’s not really that three-act structure. And I feel like I wasn’t sure whether people wanted to read that type of story when I was a young writer. And just seeing that readers from all backgrounds and all age groups have connected with Ellie’s adventure opened my eyes that there are people who want to read about Lipan teens going on fun fantasy, you know, shenanigans with all their friends. And for me, that’s what’s been the greatest part about this reception.

LD: Well, and that brings me to my request for, can I ask you for a sneak peek? Do you have anything else in the works? You just did two books in a very short period of time, so no pressure. But is there anything else on the horizon?

DLB: Oh, I wish that we did this interview just a few days later because — you know with writing, there’s always like, you have to first write a contract and then you have to wait a while for the announcement, so I can say that things are in the works and we’re getting very close to me being able to talk about the next thing. People who enjoyed Elatsoe will probably be very happy about this next thing, and that’s pretty much all I can say at the moment, but there’s something in the works. And I did just submit like five short stories to different sci-fi/fantasy anthologies for anyone who’s into that, those should be coming soon.

LD: And let me ask you too: So there are a few sort of — when you write for young adults, you know, kids are learning as they go, and so there are a few threads I could think of, you know, things that you’re, you know, kind of bigger messages. But is there anything in particular that you are hoping that your readers come away with as they’re reading these?

DLB: Yeah. And the first thing is, when I was a teenager, like I was super shy and didn’t have any friends until like college, and I finally managed to make some friends. But reading books just gave me this sense of solace and happiness, and I hope that readers can find some of that reading my books as well. So that’s the primary thing. I just want them to enjoy the books and their imaginations to be happy as they’re reading it.

The second thing is, my books tend to — even when they touch upon dark subjects, I’d like them to end with hope. I’d like readers to take away just this feeling of hope for the future, for their future. And as a geoscientist who often — I would study things related to climate change — I get how there’s a lot of uncertainty about the future and, you know, things are going to be difficult and in A Snake Falls to Earth, the main character is actually dealing with some of the ramifications of climate change in Texas in the near future. But something that I say a lot is, I do think it is my responsibility to fight for the best possible future that generations after mine can experience and not to give up, and so hope plays a big role in that and it also ends up playing a big role in my books. So that would be the second takeaway.

LD: Well, so thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today.

DLB: No, thank you for inviting me on this podcast. I’ve got to say, it’s a dream of mine to be on a Princeton podcast. Oh, and I should mention that I just married this year T, the veterinarian, and we met as Princeton undergrads, so I am very grateful for my time there.

LD: Oh, that’s so exciting. Congratulations.

DLB: Thank you. Yes. Maybe we’ll go to a reunion someday together, be like, “Hey, remember us, everyone? We’re married.”

LD: You definitely should!

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and Soundcloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

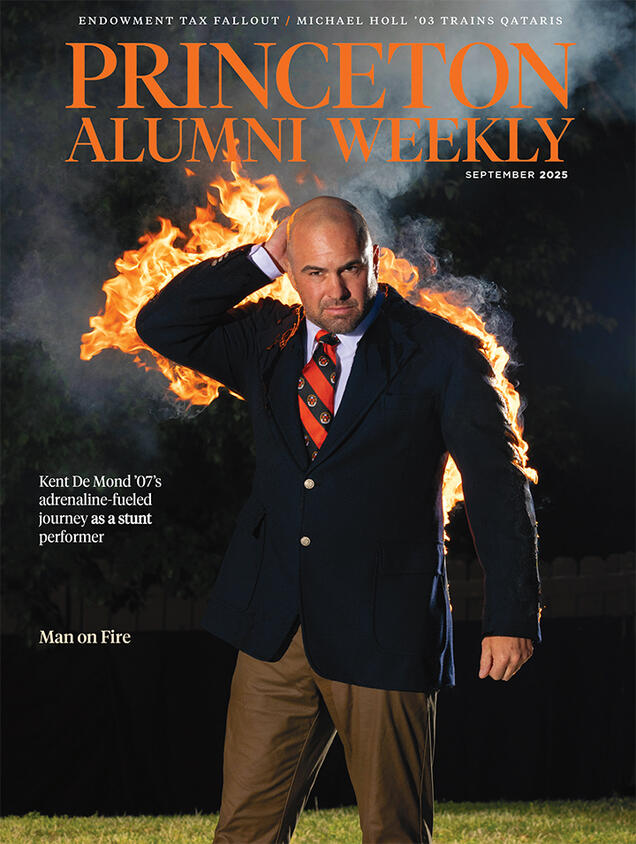

Paw in print

September 2025

Stuntman Kent De Mond ’07 is on fire; Endowment tax fallout; Pilot Michael Holl ’03 trains Qataris

No responses yet