“I was a shy person,” says Aliye Celik *70, the first female student at Princeton’s School of Architecture, “and Princeton gave me ... the backbone. I became more confident, and I carried that confidence throughout my work.” Celik’s experiences as an MFA student also shaped her career path, which includes work at UN-Habitat in Nairobi, Kenya, and New York City.

PAW Tracks is also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

TRANSCRIPT:

For undergraduates at Princeton, coeducation began in the fall of 1969. At the Graduate School, the arrival of women came earlier, albeit in smaller numbers. PAW wrote about one of the Graduate School’s pioneering women a few months ago — T’Sai-Ying Cheng, a biochemistry student who was the first woman to receive a Princeton Ph.D., in 1964. Last month, we spoke with another: Aliye Celik *70, the first woman in the School of Architecture.

I am Aliye Pekin Celik. My first introduction to Princeton University was when I was in graduate school in Ankara Turkey at the Middle East Technical University. And I got the Fulbright Scholarship, and I applied to a number of schools, and Princeton was my favorite, and I was lucky I got the first acceptance from Princeton University. And this was 1968.

I was a good student, and I was interested in many things related to architecture. But most of all I wanted to serve, you know, not big companies and so on, but I wanted to serve the poor and the disadvantaged. And it is not easy to do that when you are an architect.

I was coming as an international student, and at that time Princeton University wasn’t accepting women students. There might have been some schools which did that — I am not sure — but I think the rule for having women students came in ’69 as far as I can remember. So Professor [Robert] Geddes decided to consider me as an international student, and not pay any attention to whether I am a man or a woman, so that is how I got in. And, to tell you the truth, I wasn’t aware that it was a men’s school either.

Maybe it was a good thing that I was married, but in other ways I thought that that was not so good at the time. Because the married students were really few. I mean I don’t know, in our class I remember there were two other friends who were married. But the married students were sort of sidelined, so we didn’t live in the Graduate College, which was so important at that time. We lived in Butler, which was far away from campus and didn’t have the sort of airs of the Graduate College. That was one reason. And also there weren’t too many. We are talking about three international and three married students that I can remember, so the rest of the students, and especially architecture students — they were not too friendly with me. Maybe I can say that. Maybe they were not used to having well, I don’t know, female colleagues. So, I mean, but I was so busy, I didn’t even notice how they behaved with me. But now looking back, I don’t know who was talking to whom — my of course accent is now existing, but at that time probably it was worse. I didn’t understand most of the jokes that they were making. So I felt that I was a little bit sidelined. That is the only problem that I had.

And I had the luck of working with Michael Graves, Charles Gwathmey, Eduardo Lozano. For my thesis, I chose the topic of housing for the poor. I came to that point from a number of angles. For example, the Lozano class was, you know, he talked a lot about slums and favelas coming from Latin America. So he emphasized that part — the housing for the poor. In Ken Frampton’s history of architecture class, he taught about the Russian Revolution and its impact on the design of housing, housing for the masses, the minimum requirements of housing. Victor Olgyay’s class on bioclimatic design was sort of the parent of alternative use of alternative energies for heating and cooling, so it was also all human-oriented. So the focus was the users, and their economic condition, their health condition, rather than the design of the building. So it was really looking at the needs of the users. So I found all of that, and that had a big impact on my thinking.

While I was at Princeton, I got pregnant, so I was very careful and worried it would show. I thought it was very embarrassing to be a student and pregnant at the same time. Being the only woman, and then being pregnant — I don’t know, it felt very strange to me at that time. But now it looks very silly of course.

I had at that time had a request from the Middle East Technical University. The dean wrote me a letter saying that “we are expecting you back, you have to come and teach.” And it was something I would have liked to do. And when I got back to Turkey, I got a big surprise. When I was working so hard at Princeton University, this is the famous 1968. There were all these student movements, here, in the U.S., which I completely ignored. And in Turkey as well. So there was a big struggle between the sort of leftists and the rightists, so the dean who wrote to me was considered to be a rightist. By that time, a sort of leftist dean replaced him, and he didn’t accept me. I was so broken, I was so unhappy for a while, and I was so sorry that I left, but you know, it had already been done. But, in fact, this guy, who rejected me, did the best for my future. Because of him, I didn’t follow the academic career, but I went to the United Nations, which I really enjoyed and did what I wanted to do.

I was a shy person, and Princeton gave me sort of the backbone. I became more confident, and I carried that confidence throughout my work, and probably I could do things that I wouldn’t have attempted otherwise.

After earning her MFA at Princeton, Celik completed a Ph.D. in her native Turkey and worked for six years at UN-Habitat, the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, in Nairobi, Kenya. She returned to the United States in 1987 to work for UN-Habitat in New York City. She also reconnected with Princeton as a volunteer in the association of Princeton Graduate Alumni. Today, she lives in New York and serves as the UN representative for the organization United Cities and Local Governments.

Paw in print

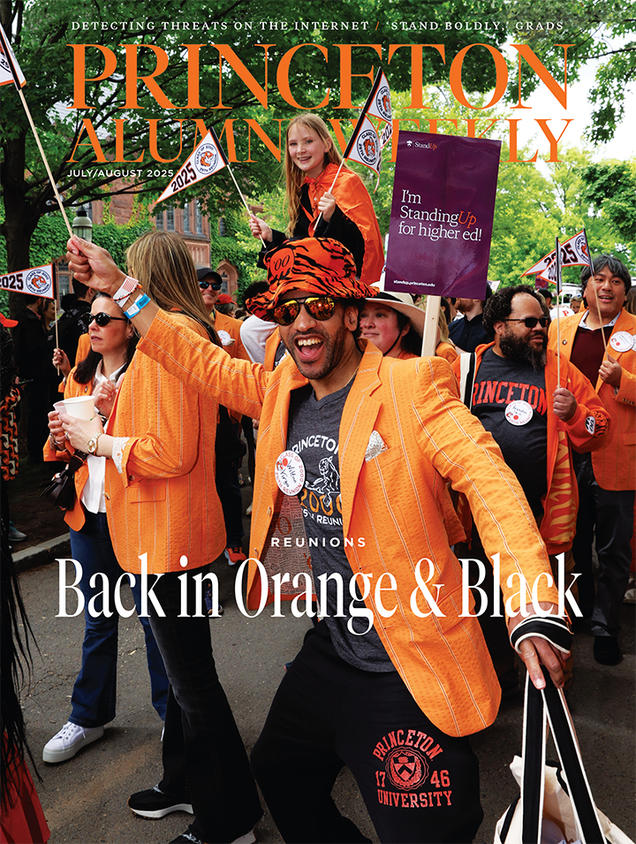

July 2025

On the cover: Wilton Virgo ’00 and his classmates celebrate during the P-rade.

0 Responses