When Hale Bradt ’52 began reading his late father’s letters from World War II, the words “just grabbed me, viscerally,” he says. After decades of research, including trips to the Pacific islands where his father served, Bradt wrote about how the war reshaped his family.

PAW podcasts are also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

TRANSCRIPT

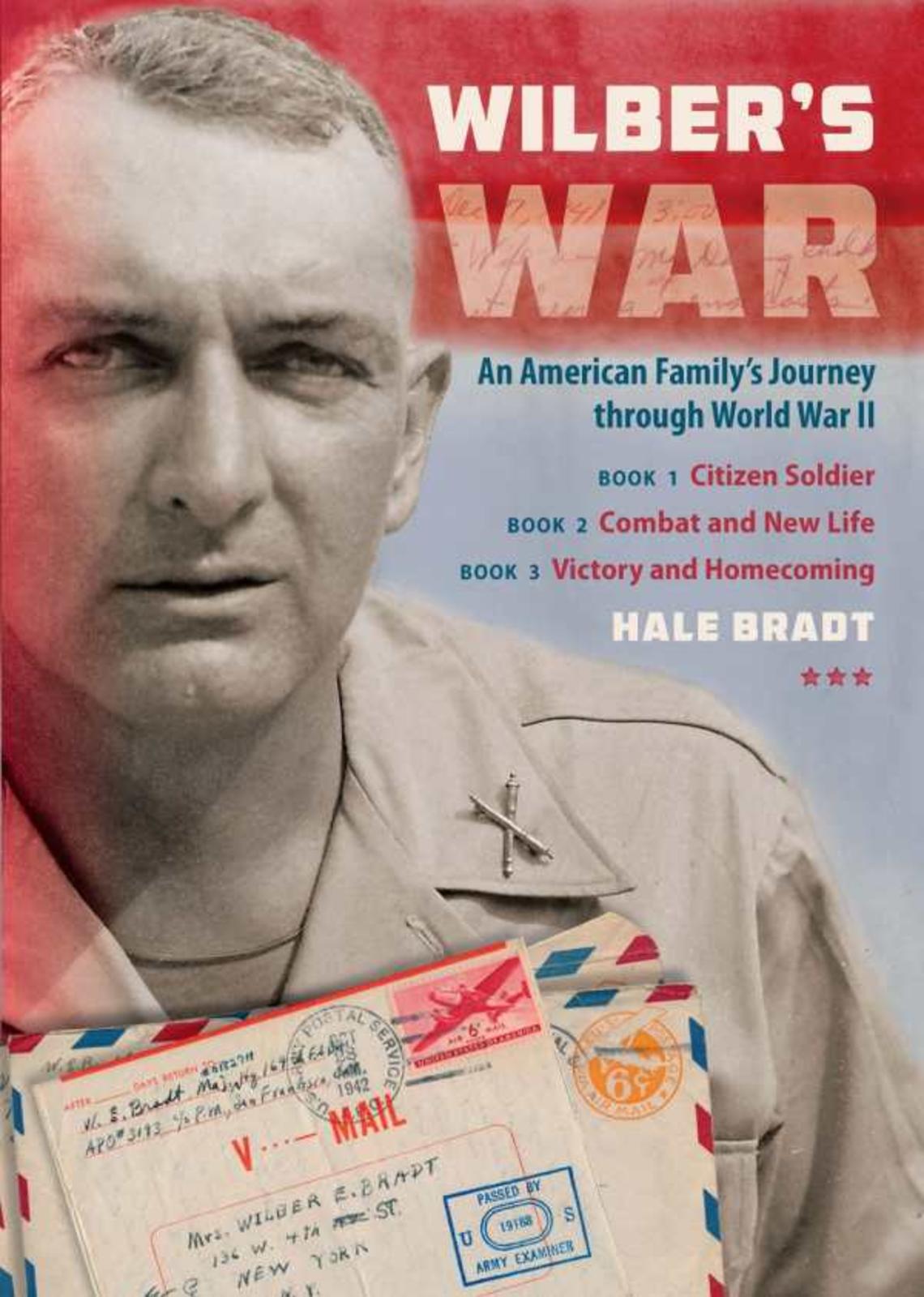

Brett Tomlinson: The cover of Wilber’s War, a family history written by Hale Bradt ’52, features shows a picture of Lt. Col. Wilber Bradt in 1943, shortly after his time fighting in the Solomon Islands campaign.

BT: In reality, it was a routine identification photo. Below the silver oak leaf and crossed cannons on his collar, Wilber was holding a board with his name, rank, and serial number.

HB: But it has a look, which is more emblematic of the story than the couple of pictures we have of him with a big grin.

BT: Hale Bradt is an astrophysicist. He spent 40 years on the faculty at MIT. But for more than three decades, he’s also been a historian, both of World War II and his family’s unique journey through it.

HB: The simple, very quick story is my dad was a chemistry professor in Maine, went in the Army with the National Guard, three years overseas, two wounds, many medals — four or five medals, several for personal heroism. He was an Artillery Commander, Major and Lieutenant Colonel, was all set to invade Japan in Kyushu, but went in as occupation forces for just a couple weeks, came home to the United States with his division, New England National Guard, committed suicide six weeks after he was home.

My mother had a baby by somebody else while he was away. Her story was equally dramatic, how she coped with that, and carried the pregnancy to term, and kept it a secret from everybody, and what was known, and what was not known, and what were lies, and what weren’t lies.

I knew my dad wrote letters copiously during the war. And I got in an argument with one of my sisters about her paternity, because then the story was that she was the Army officer’s daughter. He’d come home briefly. And that sent me to my basement. That was on my 50th birthday. That’s why my sister was in Boston. Went down into my basement and dug around to see if I had any letters from my dad, to see if the dates might help clear up the issue. And I found about a dozen addressed to me that my mother at one point had segregated out and sent to me, and I’d forgotten totally about. And I’m reading them, and I’m realizing, oh my goodness, this guy could write. By then, at age 50, I know what good writing is. And then I went crazy. And it wasn’t just the paternity story. It was, my goodness, I can learn this whole Pacific adventure through his eyes.

I started visiting the National Archives to find unit histories, National Archive for photographs, beat on the relatives and his brothers and sisters for what their life was like on the Indiana farm. I traveled on a sabbatical in Japan, and I took the — that as an opportunity to visit the Solomon Islands and the Philippines where he fought, and New Zealand. And then in the process of all that I found out the true story of my sister’s birth.

And my mother ended up, to finish the story, ended up marrying this other guy, who was a prominent journalist. But this whole business of exposing your mother’s adultery to the world — and I have one sister who was born later, who has — is not speaking to me now because I did that. And she warned me she wouldn’t. And that’s sad. But I think my mother, who always sought the limelight as a musician, pianist, and as a novelist — she never published her novel, but — I think she would be proud to be sort of the emblem of the spouses who were left home in wartime. When I was debating whether to go ahead and make it public — this was only four or five years ago — my older sister, who went through all this with me, said, “Hale, you’ve got to do this. It’s everybody’s story.”

And I took the trouble to go talk to a couple counselors at MIT. You know, they asked some pertinent questions. I don’t remember them all now, but, you know, one — I think more or less, “To what extent are you doing this to benefit yourself?”

And maybe I’m second guessing myself when I say my mother would’ve been proud in today’s context. I’m sure in the morality of the ’40s, both my dad and my mother would be horrified. But if they were immersed in the morality that we live in, I like to think that they would approve wholeheartedly, you know. I mean, to me, this keeps them alive.

BT: Hale’s extensive research provides the structure for his book of family history, but Wilber’s letters weave in strands of vivid color, from his descriptions of the nighttime jungle noises on the Pacific islands where he served to reassuring, light-hearted descriptions of his battle wounds.

HB: I began to see, you know, he wrote to his wife one way. He had her on a pedestal, you know. She was the goddess, the same kind of thing we used to do as Princeton undergraduates when there were no women here, and you’d invite somebody down for a weekend a month ahead, and by the time the month is up, they’re the Virgin Mary and you’re madly in love, you know. So he wrote to her very eloquently and poetically. He wrote to his father, and there he’s very much the boy wanting to be the good soldier for the dad. And when he wrote to us kids it’s different again. He’s trying to be the father, and trying to pick up.

They change tone during the three years. So, I sort of look back and I say, gee, what you see here is a peace-loving — well, maybe peace-loving — university professor — University of Maine — being converted to a soldier. By the time the war was over, he was a professional soldier. I mean, they made him an Infantry Regimental Commander. That was what he became totally expert at. He — and one of the problems before he died was he, quote, “Had forgotten his chemistry.” You know, he didn’t — “I don’t remember it.” So, I see that evolution now. And one friend of mine told me, you know, “You know your parents better than most of us ever knew [or] know ours.”

BT: Our thanks to Hale Bradt for sharing his story. For more information about his book, Wilber’s War, visit wilberswar.com.

Brett Tomlinson produced this episode. The music is licensed from FirstCom Music.

Paw in print

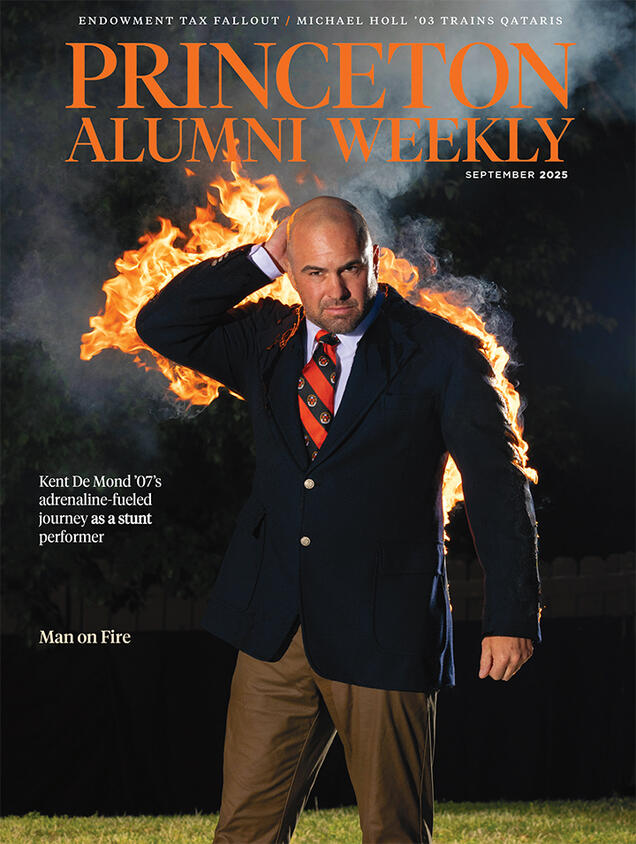

September 2025

Stuntman Kent De Mond ’07 is on fire; Endowment tax fallout; Pilot Michael Holl ’03 trains Qataris

1 Response

Hale Bradt ’52

7 Years AgoTelling a Wartime Story

Re “At Home and at War” (PAW Tracks podcast, posted online Sept. 28): I am the interviewee in this story. Many thanks to PAW and especially to Brett Tomlinson, who beautifully executed the story. You gave this old alum (me) a little morale boost and hopefully led a few more people to the Wilber Bradt story. Many, many thanks again.