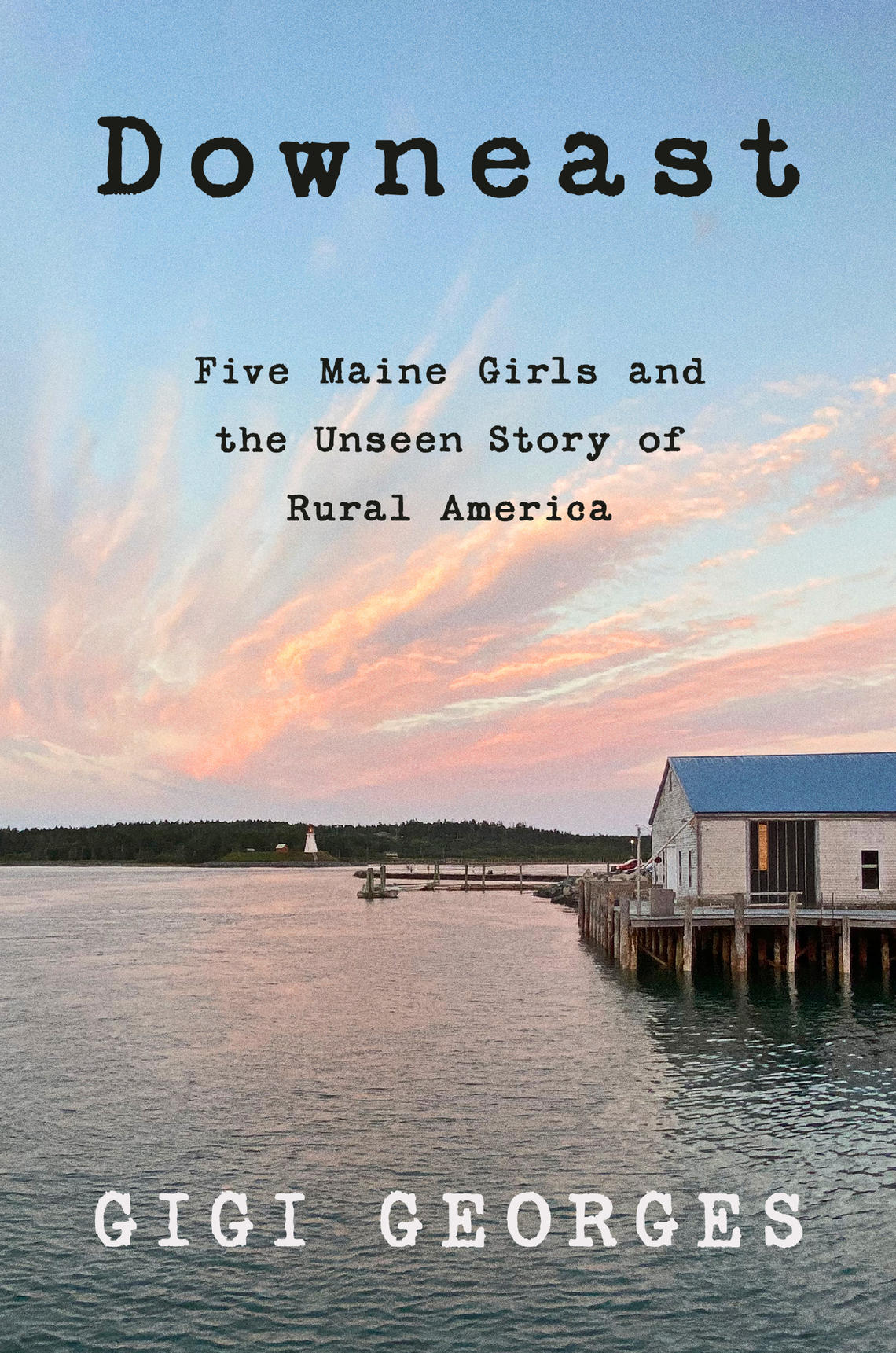

PAWcast: Gigi Georges *96 Tells the True Story of Rural Maine

‘We should recognize the value of smaller places … they are much more than the pictures of hopelessness that we so often see’

Find more PAWcasts online here

Gigi Georges *96 has worked in politics, public service, and academia — including as a White House special assistant to the president — but recently she’s turned her eyes to Maine. In her new book, Downeast, she tells the stories of five remarkable teenage girls in Washington County, a place poor on paper but rich in character and community. Through their strong ties to home, Georges shows her readers the real rural America —pieces that many Americans don’t often see.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

Liz Daugherty: On the north coast of Maine, about as far as you can go before reaching Canada, lies a wild, poor, beautiful place known as Downeast. Many people there make their living on lobster boats, and many have deep family roots, interwoven over generations. Gigi Georges spent four years here, starting in 2016, following the lives of five teenage girls, in hopes of telling a story about rural America more true than most we’ve heard: A story about tight communities, neighbors, friends, hard work and sacrifice, and the reasons why strong, bright, local girls who could go anywhere, decide to stay. Her new book is simply titled Downeast.

So Gigi, thank you so much for joining me.

Gigi Georges *96: Liz, it’s great to be here. Thank you for having me and for that beautiful introduction.

LD: So how about we start with the Downeast area? What is it like? And what brought you, a native of Brooklyn, New York, there?

GG: So Downeast, as you described it, is an absolutely stunning place. It has tremendous natural beauty, incredible natural resources, and so much openness. And, in many respects, geographic isolation. It is a place that I only came to know as an adult. As you said, I grew up in Brooklyn, New York. I was an urban kid, who was always in the midst of urban places. And as I began my career in politics and policy, focused on urban issues. So when about 15 years ago my husband — we were living then in Manhattan — turned to me and said, what do you think of moving to northern New England? I had a little hesitation. But I had come to know Maine a little bit through him. He’s the person who brought me to Maine initially. And we made that decision.

And we started to raise our daughter in essentially more rural places, in New Hampshire and in Maine. We have a place in Downeast, Maine. We’ve been there for quite a few years. My husband has been going there for many, many years. And as we began to raise our daughter, Margot, who’s now 9, I looked around and I listened to what I was hearing about rural America, that dominant narrative that is often so down beat and that promotes these ideas of hopelessness. And I thought, you know, there are a lot of challenges. But I feel like I’m seeing something else. And so I dug in, and I started to look around more deeply. And I found my way to these communities that I write about, and to these five extraordinary young women, who are at the center of the book.

LD: So what made you want to tell this story through their lens, through the lens of these teenage girls?

GG: I had the opportunity to get to know these girls really by virtue of sitting down with a dear friend of my husband’s and mine, a reverend who was then the president of this extraordinary nonprofit based in Bar Harbor, Maine, called the Maine Sea Coast Mission. And he had spent many, many years working through the mission, and through other nonprofit work, with the young people of Downeast, Washington County, Maine, which is where this book takes place. I sat down with him in early 2016, and I said, I want to know more about what it’s like to grow up in the more isolated parts of Maine. And he said, “Go up the road about an hour from Bar Harbor. You don’t have to go far, and you will find what you’re looking for.”

So he introduced me to the school superintendent in Downeast, Washington County, to the principal of the high school there. And they, in turn, allowed me to sit with a number of young people in the high school and just talk to them. When I did, I was amazed at the optimism that I saw, at the rootedness to place that I saw. I expected to see something very different. And I was particularly taken by the way in which the young women in Downeast, Washington County, were excelling, and in many ways, surpassing the boys in academics, in extracurricular activities, in athletics, in leadership, in and out of the high school. And I said, there’s a story here. And I think that I can do it and tell that story by spending time with these young women and allowing them to open up about what they experience, about what they hope, and about what they dream, and about their challenges, as well. And I found these five who were willing to let me follow them for four years. And they were great sports about it. And that’s how I started.

LD: They told you some very intimate stories. You get into their friendships, their relationships with their parents, their relationships with boyfriends, and of course, their relationship that they have with their community. Can you tell me a little bit about all of that?

GG: Yeah, these girls are really extraordinary. And when I met them, four of them had already turned 18. And one of them was 16. And I wanted to make sure that they were fully comfortable with what I was doing. And so we ended up — in many, many respects — just working together. And I initially gave them the space and the time to tell their stories. Always, always gave them the opportunity to go off the record, to rethink what they had shared, to be sure they were 100 percent comfortable with it. Because it is an intimate set of stories. And in the case of the 16-year-old, who is Mckenna, who in the story is this amazing, amazing spitfire of a young woman, who ends up being a lobster boat captain at the age of 17, after fishing her whole life. Mckenna’s mom was there with us the entire time, up until Mckenna turned 18. And even then, her mom was around, because at that point, we had become great friends.

And one thing that, I’d love to get into their stories and into sort of the broader themes that their intimate stories represent. But one thing that I was so, so pleased with was that, after this experience together, the young women have been so excited and upbeat about the way their stories have turned out. And they have embraced them. And three of them have actually, since publication, made the decision to do media, as well, and to be out there using their real names. And I was so, so pleased with that, because I wanted this, in many ways, to be something that they owned and that they felt fully, fully comfortable with. And it is a joy to see that, and to see the pride in them, in how their stories are told.

LD: So there are a few themes that I found that run through this book. And one of them is certainly the closeness among the people who live in Downeast. And as an example, I’ll tell you, I love the passage where Brit, who’s a high school art teacher who’s not native to the area, she moved there and discovered the “pace and frequency” of benefit suppers, thrown to support students who get sick, or families who experience a hardship. And she said she and her husband could barely keep up with eating that much. So can you tell me about that sense of community that you found?

GG: Yeah, it was really something else to see, and ultimately experience and be a part of, because they were so welcoming to me. And here I was, this total outsider, this “person from away,” as Mainers will call us. And they just embraced me. And what I saw was, as you mentioned, such a set of robust community networks, this sense of neighbors helping neighbors. And again, these are really challenged places. There is significant poverty. There are economic challenges. And these neighbors would just reach out to help each other, no matter what. And I was so taken with it.

It was not just the benefit suppers, which were so fun. But it was also this, that if a lobster fisherman gets injured on the job, and is laid up for a couple of weeks or more, each of the families around them will pitch in. And they’ll take up that fisherman’s hauls. It is seen in so many ways, in the ways that fishermen and blueberry farmers and others who are working so hard, and they have this tremendous work ethic, will run home at the end of their workday, and rush to take a shower so that they can get to the high school in time for the girls’ high school basketball game. And it is really fun to see. But more than that, it’s very meaningful, in terms of what we don’t often think of when we think of rural places.

LD: That was something else that definitely jumped out at me, as I was reading this: that mainstream journalists after the 2016 presidential election, there was a lot of hand-wringing. There was a lot of, we need to go to rural places to understand what’s going on. Where did you find that what they were reporting was different than what you were actually seeing?

GG: So I think that what happened was that a lot of the broader media accounts didn’t necessarily get it wrong. But I think that they didn’t widen their lens enough. So there are significant challenges. There is pervasive opioid addiction in rural places. Downeast, Washington County is in there, as well. We see it there. We see it in urban places. We see it in suburban places. But it is there. There is a dearth of economic opportunities in many rural places. And so the lens that has been trained on rural America these past few years has been significantly focused on that. However, when you widen the lens, which is what I sought to do, you see so much more. You see a set of communities that are thriving, despite those challenges. Because they are taking on those challenges together. They are not victims, by and large. And it is very much ingrained in them to band together to help each other.

In addition, what I saw was such a strong rootedness to place and such a strong connection to the land and sea around them, that that also helps sustain these communities. And so while the narrative that we keep hearing is trained on that one in a million who has to escape in order to succeed, that celebration of the one who goes off and makes it, that is not an erroneous description of what is going on in part in rural America. But it is not capturing all of the other people who want to stay, and particularly the young people who want to stay and who are, in many respects, optimistic about the future in their small hometowns.

LD: I saw that play out as these girls go from, because you’re catching them at the end of high school. So they’re wrapping up their high school. They’re going to college. And then they’re trying to figure out how to plot their life forward. And it was so interesting to see their thought patterns. And there was variety. There was one who went to Yale. And it sounds like she’s probably not coming back, but I guess we’ll see. There was one who got a scholarship to Bates, which is a wonderful liberal arts school. And after a year, you see how Downeast is tugging her back. And she looks ahead and says, you know, I want to stay home. I need the tools to build a life there. And I’m not going to find it at this more prestigious college. So she goes to the University of Maine campus. Can you talk a little bit about how you watched that play out? Because it’s exactly what you just described, on a very personal, person-by-person level.

GG: Yes. And those two examples are really interesting, as are the other three. Audrey, the one who you describe as having gone to Bates, she knew that the opportunity to go to Bates was significant. And she had the support of those around her and the excitement of those around her, to get this coveted scholarship to go. And she’s playing basketball, and she is doing well academically in her first year at Bates. But she knows that it just doesn’t quite work for her. She knows that she wants to go back Downeast. And for her, for many would look at that and say, oh, what a tough decision that must have been. And oh, how could she leave? It really wasn’t that hard for her. She knew what she wanted. She knows she wants to be a speech pathologist. She knows that she’s committed to the Downeast region, where those services are badly needed. And she is very happy and very comfortable with her family, with her friends, with her community in Downeast, Maine. And so for her, it was a very smooth transition, despite what outsiders might think.

For someone like Josie, who goes off to Yale, I watched a lot more of the push and pull. And it was fascinating to watch it. She had one foot in Downeast, Maine, and one foot in New Haven. And she grapples, in an incredible way, with such a sense of self-possession around her. She’s so mature about it. And yet, she grapples with this notion of wanting to go off and do great things. And she is an extraordinary young woman. She was the valedictorian of the high school and the second ever to go to Yale from her high school, the first being her older sister. So she comes from this amazing family, in terms of intellectual curiosity. And she struggles. She struggles with the idea of wanting to go and do great things and feeling still tied to her home, to her family, to her roots.

We’ve stayed in touch. I’ve stayed in touch with all these girls, these young women. And it’s been really wonderful to see them keep going, beyond the pages of the book. And she said to me just recently — she’s now a senior at Yale — “I didn’t realize quite the richness of the place I came from when I was going off to Yale. And even though I probably won’t return to settle, I know that I will always go back to visit family and to invest in some way in the future of Downeast, Maine.” And I thought that was really powerful. This was not a don’t-look-back story. And I can see her going on to do these really interesting things. She’s going into archaeology. And I can also see her staying committed to her hometown. And that’s pretty wonderful to see.

LD: You know, another theme in the book is the idea that young people, like these five women, may be the best hope for the future of places like Downeast. So if you’re right, and they have these ties, and they keep coming back, what do you think that future could look like?

GG: I think it’s really hard to tell what the future will look like. But I do see signs that give reason for optimism. One of the things I see is that, not just with these five young women, but with many of the young women I met, there have been choices that have been made, where they may go off to college. Or they may make a decision to go more locally. And they are now coming back or staying. And not just settling and getting married and having kids — many of them are doing that — but getting involved in the community. There is one young woman who was not in the book, for example, who had a very tough childhood, a very tough life. And she went on to get a college degree at a local college and is now serving on the board of two community institutions that, one of which is really dedicated to helping women, particularly in the community, be healthy, make good choices, and promotes women’s involvement in the community writ large. When I see her and I see that robust organization, I see reasons for hope.

Another place I see reason for hope is the way in which there is a set of community leaders that are not just from multigenerational families, which is what we often think of in rural places. But there is a small and growing set of immigrant families, many of whom came as migrant farmworkers to work on the blueberry fields, blueberry barrens. And those families now have found themselves rooted to this place. And you see young women and men thriving from these families, and now taking on leadership positions in the community, as well. I spoke with a number of these young immigrant women. And a couple of them are mentioned in the book, one in particular at the end of the book. And when I did speak with them, they said to me, “My parents had a decision to make about where they would settle. And they had worked in many places as farmworkers, around the country. And when they came here, they saw an opportunity for us. And they saw a reason for hope.” And I saw that through their eyes. And again, found another path that, to me, was reason for optimism.

So you have all of these folks coming together. You have this rootedness to place. And you have them taking on the challenges together. So I think that that bodes well, even as we keep searching for more and more economic opportunities, to help them have good reasons to stay.

LD: Towards the end of your reporting, it was 2020. And the big curve ball struck, right, which is the pandemic. Can you tell me about how COVID-19 has affected these girls, their families? And anything that’s happened since your reporting there ended?

GG: Yes. So I was toward the end, as you said, I was toward the end of the book process when COVID struck. And one of the ways in which it had a significant effect was on the lobster-fishing families. And so particularly on the young woman, Mckenna, who I mentioned earlier. Now this is someone who has, who wanted to lobster fish since she could walk. And finally, when she was eight, her dad said to her, OK. You can come fishing with me. And she knew she was going to be a lobster fisherman all her life, really. She started captaining her own boat at 17. And was doing really well, and then COVID struck.

And there was this period of tremendous uncertainty about whether or not lobster would be a commodity in demand. You had people in their homes locked down. Lobster is a luxury item. People go out to eat lobster. The restaurants were closed. And so I went with her on this roller coaster of, what would happen? And would they have, as they say, even a price for fish, as they lobster fished. As it turned out, they made it through the season, and things have rebounded. But it was a really scary time, because these are not folks who have much left behind, in terms of savings. Even though Mckenna is someone who was very conscious of saving what she earned. They have to take out significant loans for their boats and for their equipment. And so in order to sustain yourself, you have to have at least a reasonably good season. And to lose a season could mean the end. So that was really a tough situation.

And for Vivian, one of the other young women, it was a really difficult situation in a different sense, because Vivian, who is this extraordinary young woman who is so soulful and so thoughtful, and she’s a very, very gifted writer. But she made the decision to become a nurse prior to COVID. And she goes off to school to study nursing. And she ends up settling actually in an even more remote part of Maine than Downeast, Maine, and loves it. But she faces that crisis and that set of difficulties that so many of our frontline workers faced. And so we went on that journey together, as she thought about whether nursing was the right thing for her. And wondered about exposing her fiancé and her fiancé’s family to COVID. And there are some significant immune system concerns in that family. And as we have heard from so many frontline workers, there were just so many sacrifices that needed to be made. And she ultimately makes those sacrifices and commits herself to nursing and is really thriving now, having been through that experience and having made the decision to stay with it. And so she’s also just a really wonderful person and someone that I so enjoyed spending these four years with, as I did with all of these five young women. They are, in many ways, just wonderful examples of resilience and that sense of agency and strength that we don’t always see in stories about folks who face significant challenges.

LD: I think we don’t always see that in young people, either. And maybe it’s the way, it must be the way that they’re raised. It must be the ways that the families deal with the problems and hardships that they do. But one way or the other, they struck me as very mature and very forward-thinking and aware of things.

GG: Yes, absolutely. And I was really struck by that. And I think that’s right, that there is a tremendous sense of self and maturity about these young women. And it was really wonderful to see that, and to see them also grappling with some really difficult stuff in a way that was so thoughtful and so self-reflective.

And I think in particular of another of the young women, Willow, in the book, who had a really difficult childhood. And she was in a family, unfortunately, where the father had a significant substance abuse problem. And there was physical abuse in the household. And her childhood was tumultuous. She moved seven times before she was 8, and ended up moving in with grandparents. And the grandmother, which is grandmother on her father’s side, while she’s living there, is sent off to prison on a felony count. So this is not an easy situation. And yet, to your point, Willow was not a victim. She found this inner strength. She also found — and this is a big piece of the story — an incredible support system through the art teacher in her high school, Brit, who helps her see that she’s an extraordinarily talented photographer. And shows her that, by delving into that photography, she can, in fact, find a great emotional outlet. And she does that. She finds strength through her best friend’s family. So Vivian in the book, who I just talked about, who was a great writer and goes on to become a nurse in a more remote part of Maine, Vivian is Willow’s best friend. And when Willow was in a really tough situation, in terms of her home life, Vivian’s family takes Willow in. And they are there for her.

And so this goes back to those themes, around connectedness of community and social capital. And I think that that piece is also something that helps these young women be as self-assured as they are, because they know they have this strength behind them. And even though their challenges are significant, they feel that that safety net from below is there for them.

LD: It must be part of what is keeping them interested in staying, and also maybe what makes going away feel lesser than. Because if you go somewhere big, where you don’t know anyone, by comparison, it’s going to feel lonely, right? Even though you could be in Manhattan — you’re sometimes in Manhattan — and yet it would feel lonely, you know?

GG: Yes, yes, absolutely, Liz. That’s so true. And I’ve often said, in reflecting back on these five young women, their community, and this book process, exactly that. That we think of these places as isolated. We think of these places as isolated, places like Downeast, Washington County, and other rural places. And so many of them are geographically isolated. But then you get close. And you realize that, in so many other respects, they’re anything but isolated. And yet, we think of a place like Manhattan, where I lived for a number of years, where you could live in a high rise for 20 years and never know your neighbor. And I thought that the juxtaposition of those two things was really fascinating. And it’s not to say that one is better than the other. But it is to say that we should recognize the value of smaller places. That they are much more than the pictures of hopelessness that we so often see.

So when a young woman or a young man has a choice, and makes a choice to stay, we should celebrate that. Because when we reflect back to them a celebration, rather than “Ugh, why are you staying?,” that helps embolden them, too. And that helps make them feel good about their choice. So it is just another part of the story.

And I think that, when likewise we have someone like Josie, who probably will go off and settle somewhere else, perhaps in an urban area, that we should support that, as well. And recognize, too, that she is bringing something from her experience Downeast that will help enrich those places, too. And so no choice is a bad choice. But let’s recognize and celebrate the choices that we don’t always recognize and celebrate.

LD: Is there anything else you’d like to say? Or anything else you’d like to talk about?

GG: I just so enjoyed talking to you about this. And the only thing I think I would want to add is that it really was a privilege to get to know and become friends with these five young women. And they’ve enriched my life in so many ways. And I’ve often thought about it as we raise our daughter, who is now 9, that if our daughter, Margot, has half the sense of agency and the resilience and the sense of purpose that these young women have, with a real feeling of optimism, that I’ll be so happy to see her thrive in whatever environment she wants to be in. And it really is a pleasure to be able to share their stories. And I hope that readers will see in them what I saw and find a way to think a little more broadly about these rural themes.

LD: Well, thank you so much for coming on the PAWcast.

GG: Thank you, Liz. It was great to be here with you today.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and Soundcloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

July 2025

On the cover: Wilton Virgo ’00 and his classmates celebrate during the P-rade.

0 Responses