PAWcast: Jordan Bimm on the Legacy of Astronaut Pete Conrad ’53

‘Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me’

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

Conrad was an underachieving engineering student, Bimm says, but “he quickly earned a reputation for excellence behind the controls in the cockpit. ... That goes back to his time at Princeton where, by his own admission, he spent more time flying light planes than he did studying for exams.”

TRANSCRIPT

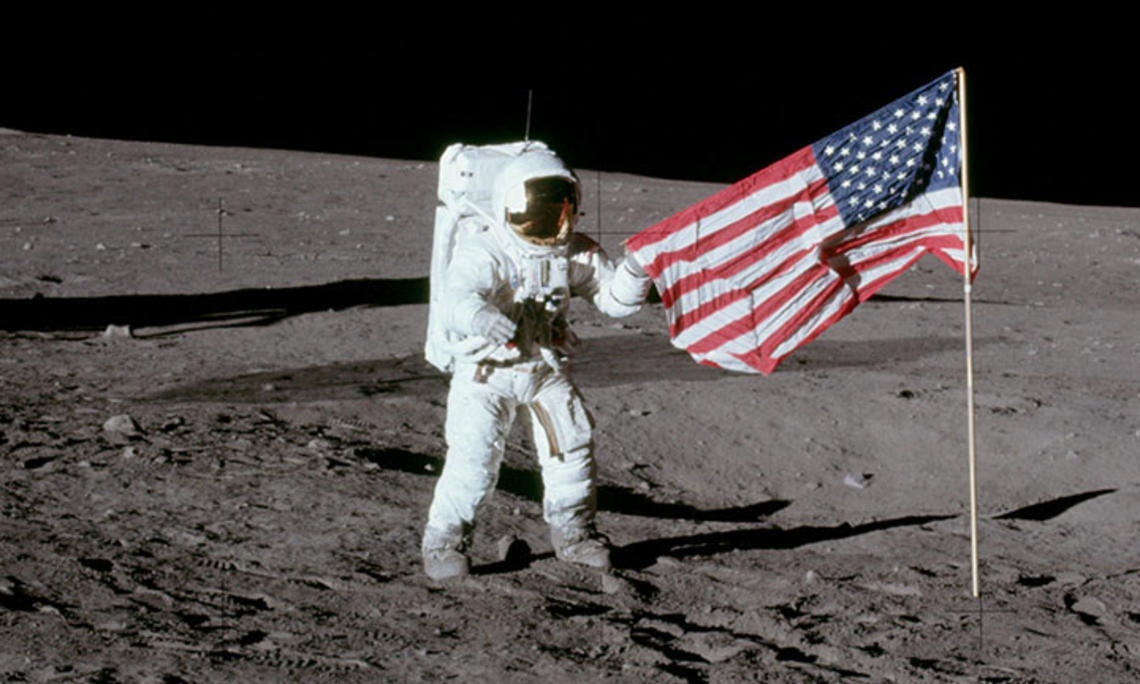

Brett Tomlinson: Welcome to the PAWcast, a monthly podcast from the Princeton Alumni Weekly. I’m Brett Tomlinson. When President Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act in 1958, Charles “Pete” Conrad ’53 was training as naval test pilot. Eleven years later, he would become the third person to walk on the moon.

Pete Conrad: Man, is that a pretty looking sight, that LM.

Edward Gibson: You're coming into the picture now, Pete.

Conrad: OK.

Alan Bean: OK, got the old camera running.

Conrad: OK. Down to the pad.

Bean: OK

Conrad: Whoopie! — Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me.

BT: November 19 marks the 50th anniversary of Conrad’s moonwalk with Alan Bean, part of the Apollo 12 mission. And to mark the occasion, we’re speaking with Jordan Bimm, a postdoc in Princeton’s sociology department and a historian of science. He’s written about early American space medicine in his Ph.D. dissertation at York University in Toronto, and his current project is called “Putting Mars in a Jar: The Military Origin of Astrobiology.” Jordan, thanks for joining me.

Jordan Bimm: Thanks, Brett.

BT: Now, Pete Conrad has a very special place in Princeton history as the University’s first astronaut. But he also has a significant place in NASA history. So, he flew on four missions, including a 28-day mission on Skylab. What was his background before entering the astronaut program?

JB: Well, as you know, he was born in Philadelphia, and came to Princeton in 1949, graduated in 1953, and then headed into the Navy. He was actually — when he was at Princeton he was on a ROTC Navy scholarship, so that enabled him to be commissioned as an ensign when he graduated in 1953. So his background was really as an aeronautical engineer, that was the degree that he earned at Princeton, and then as a naval test pilot and a fighter pilot as well.

BT: And what about becoming an astronaut in those early days — what was the selection process like? I gather Conrad was a candidate for the Mercury program and didn’t make the cut but later joined in the second group.

JB: Exactly. So, if any of the listeners out there have seen the movie adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s famous book The Right Stuff, they’ll remember the medical testing scenes. Those took place at the Lovelace Clinic in early 1959. And that was to winnow a group of about 32 military test pilots down to the Mercury Seven. And Conrad was part of that group of 32 candidates that was invited to the Lovelace Clinic in New Mexico. But he famously was not selected for the Mercury Seven, and as the story goes, it was the horribly invasive medical tests that just turned him off, and he really didn’t want to continue with the selection process. But he scored high marks, and it was actually Al Shepard, one of the Mercury Seven and the first American in space, who encouraged Conrad to reapply for the second selection, which occurred in 1962.

And it should be noted, as well, that there was another very famous astronaut who was also not selected for the Mercury Seven. That was James Lovell, who was the commander of Apollo 13 and also flew to the moon on Apollo 8 as well. So Conrad was in good company in not getting selected.

BT: What was the thinking in the selection process back then? What was the philosophy on what it would take to be a good astronaut?

JB: Well, that’s exactly the topic that I’ve spent a lot of time researching in my Ph.D. So what’s really interesting is that the field of space medicine, which is the field that surrounds the selection and protection of astronauts, is a lot older than NASA. It goes back to the end of World War II. And when NASA was created, they definitely adopted a lot of this military science that had been done, but they also made a decision, and it was an executive decision coming from the White House itself, which was that they would limit their search to active-duty military test pilots with degrees in engineering who had 1,500 hours in jet-powered aircraft.

So that limited the number of people they were looking for significantly, and sort of honed in on this sort of type of person that already pre-existed. So those are like white, male, military-trained pilots. And they also needed to have a degree in engineering. So, Conrad, with his aeronautical engineering degree from Princeton, and his training with the Navy, fit the bill perfectly at that time. So, what they were looking for within that group, though, were people who were brave, obviously — people who were psychologically stable, who wouldn’t buckle under pressure, who wouldn’t try and hot-dog it too much up there in space. So they wanted someone who was assertive and could take control, and act as a backup system to the automatic spacecraft systems, but they also wanted someone who would follow orders. They didn’t want anyone to kind of go rogue up there in space. They wanted to make sure that person could be controlled by ground controllers.

JB: That’s a great question, and it kind of links up to the story of his time here at Princeton. And by all accounts, he was a constant comedian, just someone who was really funny to be around, who had sort of a joke-a-minute, raucous attitude, real joie de vivre. And when I was doing some research into Conrad’s time here at Princeton over at the Mudd Library, I had one archivist there sum up Pete Conrad to me as a dismal student but an excellent astronaut. So when he graduated in 1953 from Princeton, he finished second-last in his class. But then when he went to train as a naval pilot down in Pensacola, Fla., he quickly earned a reputation for just excellence behind the controls in the cockpit. And that goes back to his time at Princeton where, by his own admission, he spent more time flying light planes than he did studying for exams.

He was known as someone who was dedicated to the things that he loved, he had the ability to achieve excellence in the areas that he really was passionate about, and was a very driven individual. But the overarching thing about Pete Conrad is his sense of humor. That was sort of what made him distinct amongst the other astronaut candidates that were selected in 1962.

BT: In the history of space exploration, it seems like Apollo 12 is sort of a forgotten mission, sandwiched between the first moon landing, with Apollo 11, and the heroic problem-solving of Apollo 13, immortalized in the Ron Howard film of 1995. Was Apollo 12 meaningful at the time, to sort of demonstrate that the moon landing was not just a one-time thing?

JB: It definitely was. And it has become a bit of a forgotten mission. You know, this year is the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11, but it’s also the 50th anniversary of Apollo 12, the other moon landing to occur in 1969, about four months after Apollo 11 landed.

It was super important. Apollo 11’s main mission was just to land on the moon, and famously, Neil Armstrong had to alter the landing site at the last moment because he encountered craters and boulders where they thought it would be a good place to land.

Pete Conrad’s mission was to achieve precision landing, to show that you could select a site on the moon and have a pilot take the LEM down and land very, very close to that objective. So the objective for Apollo 12 was actually a probe that NASA had sent to the moon two years earlier called Surveyor 3. And it landed in a part of the moon called the Ocean of Storms. So Conrad’s job was to set the LEM down close enough that they could moon walk over and check out Surveyor 3. And he did that.

Conrad: Boy, you’ll never believe it. Guess what I see sitting on the side of the crater!

Bean: The old Surveyor, right?

Conrad: The old Surveyor. Yes, sir. [Laughing] Does that look neat! It can’t be any further than 600 feet from here. How about that?

JB: It was a very, very short moon walk over to the probe, and they were able to recover pieces of that probe and return them to Earth after they’d been on the moon for a few years.

The other thing about Apollo 12 that makes it remarkable was that they survived a lightning strike during launch. And that’s sort of become this famous episode in the lore of space enthusiasts.

The Saturn 5 rocket is barely off the launch pad, they’re launching in a storm, which they don’t think is going to be a big deal, and then all of a sudden, the electrics in the command module just drop out. And they didn’t know what had happened, they suspected that they’d been hit by lightning, but they didn’t know for sure at that time. And it came down to a very specific switch, SEC to AUX, that Al Bean had to throw to basically reboot the power in the command module, and the mission could continue then just fine. But it was a very, very, troubling moment there at the very beginning of that mission.

And the other things that are notable about Apollo 12 was that it was an all-Navy crew, so Al Bean and Dick Gordon, who was also on Gemini 11 with Pete Conrad. They’re an all-Navy crew, and they’re also really good friends. And that wasn’t the case for every Apollo crew. So it’s a very wholesome mission in that sense.

BT: And a little footnote: Conrad took some Princeton flags up with him, which I gather you had a chance to see over the summer when you were preparing for a lecture on the Apollo program.

JB: I did. And these are sort of a fascinating little piece of Princeton memorabilia. And they are currently in the Mudd collection, at the Mudd Library in the memorabilia collection. I had the chance to go over and examine them. And I found out that there’s a very interesting story behind these flags that Conrad took with him to the moon.

So basically, it all started back on Conrad’s Gemini 5 flight, his very first flight on the Gemini program, which preceded the Apollo program. And he had gotten in contact with an administrator at Princeton, Frederic Fox [’39], who many of your readers will know as “Mr. Princeton,” and a beloved figure in Princeton lore. Conrad asked if there was a small flag that he could take along on his flight, which was going to stay in orbit for five or six days. And Fox looked around, and he could not find a small Princeton flag, he could only find ones that were huge, and too big to take on the flight. So they settled for a small Princeton banner that was procured for the University Store.

Then, in the lead up to Apollo 12, Conrad got back in touch with Fox again looking for a small Princeton flag and Fox, again, could not locate one at the University Store. So Fox got creative, and walked from his office, Nassau Hall, down Witherspoon Street, to a business that used to exist there called the Fabric Center. And he purchased a length of their finest silk, and then had another Princeton alum hand-paint the crest and the motto onto the white silk, and then his wife, Hannah Fox, stepped in, and she cut and hemmed the flags. And then the flags were sent directly to Cape Canaveral, where they were vacuum-sealed inside Pete Conrad’s “pilot’s personal preference kit,” which was essentially a small bag that they could bring whatever they liked in there. And he took that bag to the moon, containing the flags.

And then when the flags made it back to Earth, Conrad presented them back to the University at a ceremony that was held at the Colonial Club, the eating club where Conrad had been a member when he was a student here. And I think it’s so funny to think that these lengths of silk were taken from 25 Witherspoon Street, which is now the location of the restaurant La Mezzaluna [“the crescent moon”] — which is sort of fitting — taken from Witherspoon Street all the way to 40 Prospect Avenue by way of the moon.

BT: The lengths that alums will go to, to serve Princeton.

JB: Exactly.

BT: I also mentioned Conrad’s later Skylab mission, 28 days in space, which at the time was a record for human space-flight duration, and something that he was rather proud of. After NASA, he had a career in the aerospace industry; he died relatively young in a motorcycle accident in 1999. What do you see as Pete Conrad’s legacy in the space program?

JB: His legacy is the third man on the moon. The third human being to set foot on another celestial object. Apollo 11 was successful, but there were so many unknowns still at that point, and the replication of something like that was crucial. You needed to show that you could do it more than one time, or else it could be explained as a fluke, or a one-off, or something like that.

He really demonstrated competency, and he demonstrated precision flying, landing that LEM so close to Surveyor 3, and that speaks to the overall picture that we have of Pete Conrad as an excellent pilot. I think also a part of his legacy, as I mentioned before, is his sense of humor. And you get that from the first words that he spoke on the lunar surface, which kind of poked fun at Neil Armstrong’s “one small step” gravitas. So Conrad famously said, “Whoopee, that may have been a small one for Neil, but it was a long one for me.” Which was a little bit of a reference, I think, to his own short stature. He was only 5-foot-6, so the distance there from the bottom of the ladder to the foot of the LEM was a bit longer for him.

BT: With the Apollo 11 anniversary over the summer, much attention has been paid to the early days of NASA, and you’ve done research on the space program even before that. Are there lessons from that era that could apply to future manned space travel?

JB: I think so. I mean, it was an era characterized by the competition with the Soviet Union, and that was the number-one reason we got the Apollo program and why humans have set foot on the moon now.

In our present moment, we are sort of absent that motivator, and we’re in a transition point right now, similar to the way that the space program transitioned from sort of an obscure military operation in the 1950s to a huge national program when NASA was founded in 1958. Right now, we’re at another juncture where we’re sort of leaving behind those large national space agencies and transferring to the private space industry with Boeing and SpaceX, Blue Origin, companies like that really trying to demonstrate human space-flight competency.

We are in a transition period right now where we could learn a lot from the boldness of the early space program. Right now, people want to make sure that things work really, really well, and are safe before they put a human inside, and I think that’s a great idea. But at the same time, there is a bit of, I think — we’re at a bit of a moment where we’re unsure if we want to go all-in on private space or if we want to keep doing the large, national space agency. So something like the space launch system that NASA is developing right now may not end up being super useful if SpaceX sort of takes over the commercial crew program.

BT: Another topic that has been part of space exploration from the beginning is one that’s at the top of your research agenda right now, the field of astrobiology. What role did the search for life play in the early space program?

JB: That’s a really interesting question. So astrobiology, for people who might not be familiar with the term, is the study of hypothetical extraterrestrial life. So we haven’t found any life on other worlds yet, but there’s a lot of science being done on the potential for that life: what it might look like, where we might find it, how to look for it, how to identify it, that sort of thing. And listeners shouldn’t be confused with SETI, which is the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. So when we’re talking about astrobiology, we’re not talking about people with headphones on listening to radio telescopes. We’re really talking about microbiologists hunched over a bench, looking through a microscope at microbes.

That was definitely something that was animating early space exploration, in the sense that, if you look at the Apollo 11 mission, and the Apollo 12 mission as well, those astronauts, when they returned from the moon, were quarantined for a period of weeks because they didn’t know if there was some sort of life on the moon that could come back to Earth and infect the population. Obviously we now know there is no life on the moon, but we are still very hopeful that we might find life on Mars, either present life or life in the very ancient past when Mars was warmer and wetter, as well as now the moons of Jupiter and Saturn — places like Enceladus and Titan are looking like good candidates for life on other worlds.

The period of time that I’m studying, though, predates NASA. If you ask an astrobiologist today about the origin of their field, they will likely tell you a story about how Joshua Lederberg, who was a Nobel-winning molecular biologist, lobbied NASA in the very early days of funding, for a program that he called exobiology, and that sort of began the field of astrobiology in the 1960s. But what I found out doing research on the very early military period of space development, was that the U.S. Air Force actually had a program in what they called astrobiology running from about 1950 to the creation of NASA, and that that sort of early military period has been forgotten from the field.

One of the most interesting things I found during that era was that they created these little tiny simulations of Mars that they called “Mars jars.” So if you can imagine, like, a little terrarium that you might build at home with cactuses or succulents inside, these were military officers building versions of that, except for Mars. So instead of your plants, you put in very arid soil, you make the atmosphere extremely thin, you make it very cold. And then what they were doing in the Air Force was putting extreme microbes from Earth that they thought could survive these extreme environments inside these Mars jars, to see if any could survive. And what they found was that after a period of a hundred days, that certain Earth microbes could survive in what they though the harsh conditions of Mars were like. So that did create some hope for finding life on Mars. That still animates a lot of space exploration today, although mostly robotic probes that have been sent to Mars.

BT: A final question for you, and I know it’s very hard to predict where space exploration is headed. But if you were to be given moonshot-type money, what question or questions would you most want to explore?

JB: That’s a great question, and I think the question I would want to explore is making space more democratic of a place. And right now, we have seen sort of the legacy of the military space program create a certain type of astronaut. I would like to see a more diverse population of people exploring space. I would like to see people with disabilities, LGBTQ people included in space missions that haven’t been to space yet. I would like to see space sort of opened up for everybody and to sort of make right on those proclamations that we have heard about making space for all mankind. I think so far it has been for a very specific type of person, and a very specific type of mission, and I think that there is a lot of room to grow there. And if I was given moonshot money, I would definitely try and open up space to all different kinds of people, and to have all different types of experiences there. Artists, poets, musicians, not just engineers, not just scientists, not just test pilots — as brave, and as competent and as heroic as they are, there is so much more to life than that. Space can offer a reflection of that that would be so valuable to everyone back here on Earth.

BT: Well, Jordan, thank you so much for joining me. This has been great to speak about Pete Conrad and some of your work as well. And good luck with the remaining time in your postdoc.

JB: Thank you very much.

Bean: Hey, I just threw something. It hasn’t hit the ground yet; it might have gone up 300 feet. Boing!

Conrad: Stop playing and get to work. C’mon, maybe they'll extend us until 4 1/2 hours. I feel like I could stay out here all day.

Bean: I know it.

Conrad: — if the air holds up.

BT: If you’ve enjoyed this podcast please subscribe, you can find us by searching for Princeton Alumni Weekly on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. And transcripts of every PAWcast are available on our website, paw.princeton.edu.

This episode was recorded at the Princeton Broadcast Studio with help from Daniel Kearns. The music is licensed from FirstCom music.