PAWcast: Majka Burhardt ’98 on Motherhood and Mountain Climbing

‘There’s a deeper conversation about parenthood and motherhood to be had’

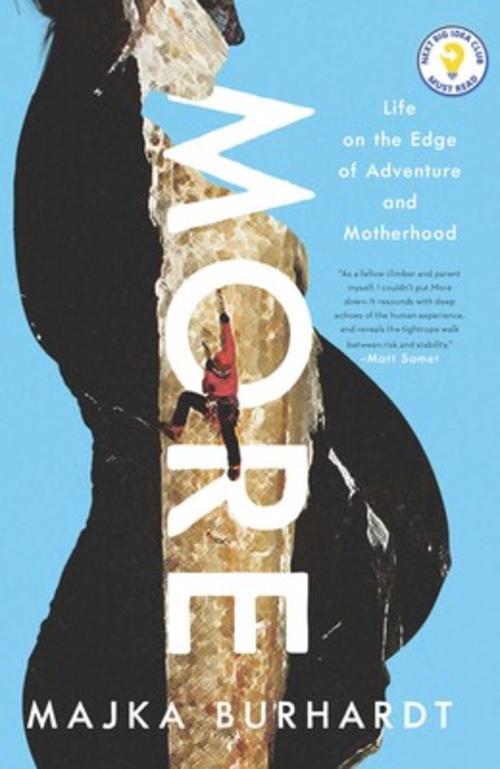

What happens to us when we become parents? For top professional rock and ice climber Majka Burhardt ’98, having twins knocked her world off its axis, raising major questions about her identity, her past, and who she wanted to become. In her new book, More: Life on the Edge of Adventure and Motherhood, she shares the raw thoughts she recorded during her transition to parenthood, and on the PAWcast, she explains why our culture needs a deeper conversation about motherhood — and how this book can help.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT:

So, Majka, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today.

Majka Burhardt: It’s wonderful to be here with you.

LD: So, this book was really unlike anything I’ve ever read before. What made you decide to publish it?

MB: I really am interested in the rawness of humans and the human journey. And I realize that I wrote this book really unintentionally. It was a series of audio journals, and notes, and emails to myself when I was going through pregnancy and early motherhood. And when I saw that there was a story there, that I could stitch it together, to me it wasn’t an option not to publish it. It’s like, well, wait a second, I would love to read someone else’s journey of what it really — what’s really happening. Not in a retrospected, not with kind of blurred edges, and saying, “Oh, it was — I remember it was kind of hard when my kids were, you know, a year and a half and I was trying to help them to go to sleep, once again, doing sleep” — it’s like, no, what does it really feel like when you’re in the maelstrom? And I — it’s almost — I became someone who was willing to take the hit for doing that personally.

I think that there’s a deeper conversation about parenthood and motherhood to be had, and the way we have it is by being honest about what’s happening in the moment of the experience. And I think that this book is a glimpse into that.

LD: So, if you could start maybe by talking about rock climbing, because that’s where you began, right before you got pregnant, rock climbing and ice climbing was this huge part of your life. Can you talk a little bit about how that work that you were doing was tied up with your sense of identity and your sense of self?

MB: Yeah. You know, actually, when I was at Princeton, climbing really took off for me at that point. I took a year off to climb full time between sophomore and junior year, and at that point, you know, received a fair amount of recognition for the climbing that I was doing, as a young person and as a young woman. And my climbing career really took off at that moment. And climbing became who I was. It was, you know — I wasn’t just a woman who lived in Colorado. I was a climber, and then I was a professional climber, and I was a mountain guide.

And I was always driven, from a very young age, to do things intensely in the outdoors, but I also wanted to do things intensely professionally. Whatever that profession was going to be. And I didn’t, you know — like no one does, I didn’t really know what that profession would be when I was younger. But as I got older, I realized that I could pair climbing with a profession that was in the quote, unquote real world. And therefore, that climbing identity kept being so important to me, because it was also what made me truly me, so that I was a writer, but I was also a climber. I was a professional climber when I was a writer. I was a professional climber when I was being a journalist. I never just tracked into another career without climbing being on top of it. But it also meant that climbing, I now understand, was one of the most important things in my personality, like, profile that I gave myself and that I held onto most tightly.

LD: So, how did motherhood fit into that person that you were? What changed? That’s the question of the book, that’s the whole book. But can you tell — how did that happen? How did that go?

MB: Well, as I talk about in the book, I didn’t think any — I didn’t think much was going to change, because I thought that I would have one child, and I’d kind of tack into my side, and we’d go off in the world, and it would be wonderful. And then I found out I was having twins. And, like, my entire house of cards collapsed in front of me, and I thought, oh, wait a second. I know that I was already probably being a bit naive, but holy cow, I’m no longer in charge of what’s going to happen next.

So, for me, I really had to start from a place of curiosity about what motherhood was going to be for me, what even the process of being pregnant with twins was going to do to my body. I could not be the pregnant, climbing, warrior goddess that I envisioned that I would probably be if one day I might get pregnant. Instead, I was really psyched if I went on a walk, you know, I had to really give into the formation of a new identity and I had to realize that whatever path I was on as a mom, as a climber, was not an even trajectory. I was not on some sort of like hockey stick curve to greatness. I was on a very bumpy road that was going to have a lot of changes along the way.

And I think that’s what motherhood has taught me is that change is a thing that you can count on when you suddenly are taking care of humans who are changing all the time. And if you’re not willing to be changing all the time next to them, then it becomes even harder.

LD: Did you find that what you were experiencing was not the mainstream narrative? Like, I will tell you, I have two children bracketed around yours, so, I had one in 2015 and one in 2017. The narrative that we tell about working mothers does not feel like it is telling the whole story. Did you find that when you were going through it —

MB: Oh yeah, I definitely found that. And I also found that, you know, I don’t think it tells a whole story for anyone. But when you — every individual has their unique thing that they’re trying to not just work and be a mom, they’re also trying to be themselves, whatever the representation of themself is that is outside of work and motherhood. Right? Because it’s not a binary. It’s work, and motherhood, in my case, climbing, and in my case, you know, also maintaining my marriage, and trying to learn things about what happened in my family at origin, and all those things were smushed up together.

But the examples that we have are, you know, make sure that you take time for yourself, and be a working mom, and get this done, and, you know, and — it — like the — they don’t — I don’t think they fit any of us. But they certainly didn’t feel like they fit the paradigm that I was in and also sort of this crashing reality of having created a very alternative lifestyle and a very alternative career, and then doing one of the most normal things you can do in the world, which is having children, right? And, you know, having those things set up against each other.

LD: It does feel sometimes like women are expected to be able to do it all. You’re told, you can have it all. And then when you try to actually do it, you discover it’s a lot harder than you think.

MB: Absolutely. I think that the all is the thing that we need to understand better. What does “all” mean? And if you can do it all, your all might have to shift. And that’s what I really, like, became more comfortable with. My all for today (laughs) is that I’m going to make sure that if both of my kids have hand, foot, and mouth disease, as I talk about in the book, and, you know, in the moment, and it’s, whatever, negative 20 as a high today in this incredible polar vortex that’s happening in New Hampshire, and my husband happens to be traveling for work, then my all today is surviving through this day. Not also making sure that I get a — that I’m going ice climbing today. Not also making sure that I’m going to work an eight-hour day and move the needle with my team in Legado, working in Mozambique. That you have to be willing to adjust the all and it has to be on your terms, otherwise it’s, becomes really untenable.

And I think that that was a big thing that I learned in this process of early motherhood, next to the fact that change is going to happen all the time is that you — the way that we seek balance is actually a day-to-day achievement. And balance isn’t some overarching structure that we’re trying to have someone else add up for us. It’s these moments of saying, did I do all the things I needed to for myself today? Did I — was I a good parent for some moments of today in a way that I can be proud of myself? Maybe not all the moments, but for some of those moments can I say, like, yeah, I did a good job? Did I learn? Did I try really hard? Did I fail a couple times? That became how I understood balance and I never knew that balance could be broken down to, like, that level of granularity before I went through motherhood.

LD: Something you said earlier really struck me. That you were willing to take the hit for being the one to say all of this out loud and being this real in a book. So, what are you hoping this book does for the conversation and for your reader?

MB: What I really hope is that it normalizes that something like being a mom can be so hard in the moment, and so interesting, and so much what we want, and just the complex rollercoaster of emotions. And not in some, you know, sitting in the back of your chair with your arms folded, and saying, yeah, it’s a really big deal to become a parent. But, no, this is what the hot mess of it looks like, and that by normalizing that, and making it OK and welcoming people into that space that I think that it gives us all a sort of a tapestry that we can see, and weave our own iteration of the things that we’re struggling with and the triumphs that we’re going for.

Because it’s not all a struggle. I love my kids, I love being a mom. But having to pick a narrative, like, pick a lane didn’t work for me. It’s — and what I was having a really hard time with is these are the types of conversations I want to be in with other moms, right? But oftentimes you can’t, because you’re talking to them over your toddlers running around, and you’re not having a real conversation, and you’re too tired the rest of the time, or you’re always talking about work. And so, for me, these are the conversations that I most desperately was looking to have and I decided to have them, I guess, with my — you know, the people who are reading this book. And also to call people into this — to a larger dialogue about if we’re really talking about shifting how we support moms and we — and parents, then we need to be doing that by first looking at what their real experiences of becoming a mom and a parent, and not through an anesthetized, backward-looking lens.

LD: That conversation does seem to be changing. But the dominant narrative for a lot of working women seems to be too often: You can have children, just don’t let anyone see it. Don’t let it affect your work, don’t — you got to work like you don’t have kids, you have to parent like you don’t have work.

MB: Yeah. And then you have the pandemic.

LD: Exactly.

MB: And I think that’s why we’re in such an, like, a fascinating time right now. Because the entire world went through change, and went through this huge disruption, and you could no longer work like you were. If you were a working parent, you could not separate those. One could argue you couldn’t earlier either, but you sure as heck couldn’t do it if you were working at home, and you were managing your kid, and you were remote schooling, and any of the different iterations.

And now, I think, there’s this reckoning that’s happening, that’s saying, hold on, why are — there — something changed, and let’s understand what this change is, and let’s fight to come out of this with a better working knowledge of how to do both of those things together.

And I think that we’re in a really important inflection time in — certainly, in our country — around this, and I think that it just — I’m finally in the right place at the right time, which doesn’t always happen in my life, (laughs) to be part of that conversation, and to say, for me, it again comes down to the change narrative. And that so many of us are saying, wait a second, I don’t want to go back to what this was like before the pandemic happened. I want to have nuance in the fact that these are both things that I’m doing and I’m integrating, but we need some better models for it, and we sure need to have it be safe to have the conversation, and to navigate our way through it.

LD: Let me switch gears for just a second, because I did want to ask you about your work with Legado, which sounds like a really interesting organization. You did a lot of the building of it while you had newborns, which is very impressive. Can you tell me about the organization and what it does?

MB: Yeah, so, Legado tries to solve a fundamental equity issue we have in our world, which is that the right to plan your future is something that is not seen as universal. Think about it this way, like, we just talked about what happened with COVID, and the pandemic, and the fact that we all know that change is happening, and we want to be able to start dictating more of our own terms for how we want to live our lives. And yet, the way most international conservation and development happens is that there is a solution that is brought in from the outside and laid upon local indigenous people as the solution to a problem which they may or may not have, or a need that they may or may not have, but they don’t get to run the terms of the entire container of actions that they want to take to create a place where their people are thriving, their families are thriving, and their environment are — is thriving.

So, what Legado does is we flip that and we work with Indigenous people and local communities to chart a path that’s unique to them about what we call a thriving future. So, where they’re thriving people in a thriving place. And then all of those external actors are working with those communities on their terms. They’re the driver and the decision-maker on what choices they want to make, and how they want to change it, and how they ultimately want to have success.

LD: That’s interesting. I remember there’s a part in the book where someone in — at the original mountain where you were — where you guys got started was saying to you, “It’s great that you want to do all this conservation, but we need help sending our children to school and we need help with food and things like that.” And you were like, “Well, but that’s not what I’m doing.” It makes sense that if you care for the people who live in the place, that that’s going to be part of caring for the place.

MB: It hugely makes sense. But it’s so backwards that that’s not the way that work is — that’s not how we have set up conservation. That we’ve — there’s so much focus on have a mission, and fulfill the mission, and be very clear on it, but what you’re divorcing from that is humanity, because I surely couldn’t be on Mount Namuli in Mozambique and hear that the Lomwe people that I was there to support them, to take care of their forest, were telling me that they had other needs and I had to say, “I can’t help you and I can’t listen to you?”

Because actually, what I am, is a generalist. And what I am is someone who spent my entire life building teams to get things done. That’s what it means to be a climber. That’s what it means to have run expeditions all over the world. And I’m like, wait, I’m not a conservationist. That’s not the cape that I’m wearing. Instead, I can say, OK, let’s talk about this. What do you need to have happen? How could I help you make that happen? How do I get out of my own way with my own agenda and listen to your agenda without boundaries? Not just your agenda for how you want to protect your forest, but everything that you and your community wants, so that you get to be the leader on it. And like you were saying, it’s — it seems very simple when we talk about it in these terms, but yet this is not the way the work is done.

So, Legado really made a pivot when the kids were quite little. I just couldn’t reconcile being a mom, and doing the learning that I was doing in my life, and being attached to these two beings, with not showing up in a more human way with this organization that I was building. It felt too divorced. And so, we made a really radical pivot, and stepped away from the traditional conservation lane, and really became a social change organization. And that’s what’s driven us to grow now. We’re working in Kenya, we just have a partnership with the Machiguenga Communal Reserve in Peru that began last winter, and we have partnerships in Rwanda, in Ethiopia, and Australia that are knocking at our door as we grow.

LD: That’s so interesting. It’s like how becoming a mother sort of opens up this whole window into a world of life that you weren’t really tapped into before. And it’s interesting to hear that that changed your work, as well as your self.

MB: I had a really big choice to make. I could have given up on Legado when I became a mom. And things were really hard. I mean, at one point, and I talk about it in the book, we got some $11,000 invoice that I was like looking at the bank account and thinking, am I even going to be able to pay that? While I was being told that we were about to get a quarter million dollars of funding in our biggest, like, single-shot funding tranche and the cognitive dissonance between those two things was nuts for me. And I could have very easily said, “I’m going to take a different route or I’m going to stay in the known lane and just head down, do conservation.” Because that’s also what all the funding wanted us to do, is like, here you go, you want fencing, you want patrols, let’s go traditional conservation.

Instead, I said, no, I want to make this harder, and more complicated, and scarier, and what happened is that it worked. And it worked by attracting this amazing team, funders who really believe in this approach, and I think that — it’s how you said it, Liz, is exactly correct — it’s like, I couldn’t, in good consciousness, be growing and changing as a mom, and not be applying that to this organization that was mine. It might have been different if I was working, if I was punching a time clock, and I was like, you know what, this has this function, and this is how my family gets health insurance, and I can do this, and I can come home at the end of the day. I started Legado with $11,000 — apparently a very thematic number in my life — but I started Legado with $11,000 and a crazy idea, back in 2014. So, I — you know, there’s ego involved. I wanted to make it work, but I knew that the way to stand behind it was it had to work in a way that I was proud of. And what I was proud of was changing dramatically along the way.

LD: Now, let me ask you, are you still climbing?

MB: Yeah, I climb all the time. So, yeah, it’s climbing has — I had to stop climbing for a while when I was pregnant, because I had too big of a belly, although I thought that I was going to be able to pull it off, it wasn’t as possible, especially because when I was — you know, during the time that I probably would have been able to climb more was ice climbing season, and it just didn’t feel right to have shards of ice falling at a belly that I was trying to take care of and grow two humans in.

But, yeah, I’m climbing, I ice climb, I rock climb, you name it, it’s a big part of it. And part of the — one of the ways I’m able to do it is, where I live in northern New Hampshire, there’s a lot of climbing that’s really accessible here. So, you know, I spent Monday and Tuesday doing amazing ice climbing with a longtime friend and mentor of mine, and I was able to drop my kids off at school, and send texts in between climbs to my team at Legado, and come home, and be with my children, and put them to bed, and go back to work for two hours.

LD: Do you still worry about the risk of it? Because that’s a big thing in the book. You keep mentioning these, you know, amazing climbers who fall and die. Your — it kind of keeps happening in your book. It’s not like, you know, droves of them or anything. But it was interesting, because your risk calculus before you’re a mom is going to be different. Can you talk about that at all?

MB: I think that from the outside, we think that you make a choice about how much risk you’re going to take, and that then you go, like, live in that lane. Risk is actually very adaptable. And on a daily basis, on an hourly basis, on a minute-to-minute basis, you’re making choices around risk as a climber.

You might — you know, let’s use example of ice climbing. I was climbing two days ago and we’ve had this huge cold snap that happened a week ago, and then it got really warm, and so you’re going out, you’re thinking, wow, that ice has been through a lot of stress. So, it means that it might seem really plastic, but it actually might be really breakable. So, I need to make choices, I need to understand risk differently today than I would have a week ago on the same climb.

And for me, that’s sort of like parenthood. There is — for me as a climber, what I think about climbing is not a fixed entity. I don’t say, “I can’t do this, because it’s too risky.” It’s saying, “In this moment, what feels like an acceptable amount of risk for me in this season of my kids’ lives? In this month, in this season of winter, in this day, when these are the conditions?” If my kids are sick, if suddenly my husband and I are both not available, we both have objectives that are going to take us out of cell phone service, that feels too risky. Like, I can’t do that. I don’t want to get the call from school and have it have to go down the call tree so that their grandma that lives an hour away is the person who’s driving to pick up a puking kid. That doesn’t feel like the right fit. So, thankfully, I live in a place that gives me some adaptability around that.

But, as you point out, in the book, you know, I talk a lot about losing a lot of friends. Not only during the time when my kids were little, but over my whole life as a climber. And I’ve always been really aware of the consequence of, like, the worst consequence possible of being a climber, and of losing your life, of leaving your loved ones behind, and when I became a mom, that became all the more pronounced to me. And the thing that it has reinforced is that I want to climb and come home. That’s my bottom line. I want to do both. I don’t see it as I want to climb at all costs. There — you know, you might say, well, who would say that they didn’t want to come home? But I will tell you that some climbers have an ability to be bold enough where that’s — those two things don’t sandwich up next to each other right away, with immediacy. And for me, that’s sort of my moniker. It’s like, I want to go climb, I want to go have a ton of fun, I want to push myself, and I want to be there at pickup for my kiddos. So, how do I do that and how can I achieve that?

Now, my kids are also still pretty little. They’re six and a half. You know, when they’re 12, when they’re 15, am I going to be more comfortable going back and doing big expeditions? That remains to be seen. I know right now, part of it, Liz, is that the work I do at Legado has its own risk in it, right? It’s risky to run your own organization. You know, I travel, I burn some of my time away from my family, so to speak, by going to be with my team in Kenya, by going to be with my team in Mozambique. So, there’s a choice that I have to make to say, do I also want to go on a personal climbing trip when I was in Mozambique a month ago? Does that feel like the right calculus for the health of my family? And because I’m running Legado and I’ve built Legado the way I have, it’s also changed how many big international climbing trips I’m doing, because I’m focusing that time — like, I’m sort of spending that in Legado money.

LD: That makes sense. It sounds a lot like parenting itself, where you’re constantly changing what you do. As soon as you think you’ve got it figured it out, you have to adjust. Sounds like the same thing with your risk calculus. The day, the rock, the ice, what’s going on, constantly making those decisions, and it’s within those decisions that you find your safety, right?

MB: Exactly. Yeah, and it’s — and the other thing that comes into it as a parent is, did I sleep last night? Did I have a kid waking up at 2 a.m., because they had a nightmare or their tooth felt funny, which is our recent thing that’s happening right now, right? And so, I might not be my best self right now. I might not be as reliable to make the choices that I need to make to have, like, high-consequence, high-level implications of my actions. And you — if you’re not rationing that down, in my opinion, then you’re not really an accurate — like, you’re not a reliable narrator of your own life and of the choice that you’re making at that time.

LD: Well, let me ask you just one more question. Your book goes into a lot of detail about some of the parts of motherhood that we don’t always talk about, because not everybody wants to hear them. Having been through it all, would you recommend parenthood to someone who is considering it?

MB: Oh, I think parenthood makes us better humans. I think parenthood makes us understand the world. I would absolutely recommend it. And it — and I would say do it, and be ready for it to rock your world, and bring you to your knees. Don’t do it if you think that you’re going to be in charge for the rest of your life and that’s the way that you find your ultimate happiness. But if you have an inkling that you’re ready to sign up on a different agenda, then there’s no better way than diving into parenthood.

LD: I love that. Well, that gets through the questions I had for you. You know, is there anything else you wanted to say?

MB: I love that you said that I talk about things that aren’t discussed as much. I mean, I think it kind of comes back to that intersection of being a working mom and that — you know, when you said work like you’re not a parent, and parent like you don’t have work. We so need to be able to be a working — you know, I need to be able to go on my LinkedIn and say, I just wrote a radical book about motherhood, and in that book — I — right, because those — we are doing ourselves such a disservice if we’re not willing to jumble it all up together. Because that’s what the reality is. And I think that, you know, that’s really the conservation that I’m trying to be a part of and that I’m really fascinated by is that how we get to more support for women, how we get to a deeper understanding for working parents, is actually being in the middle of it all with them, versus trying to help them continue to segment it out of their lives. Let’s get into the messy middle and let’s find a solution in that pathway.

LD: Well, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me today. This is really interesting and I really appreciate your book.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and Soundcloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.