PAWcast: Peter Yawitz ’80 on Navigating Workplace Culture

Whether face-to-face or in a text, communication is key

On this month’s PAWcast, Peter Yawitz ’80, author of the new book Flip Flops and Microwaved Fish: Navigating the Dos and Don’ts of Workplace Culture, gives advice on communicating with your coworkers, dressing the part in an office environment, and preparing for difficult conversations with your boss. He also has a few tips for managers who tend to be dismissive of the millennial mindset.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

Brett Tomlinson: Welcome to the PAWcast, I’m Brett Tomlinson. My guest this month is Peter Yawitz ’80, the author of the new book Flip Flops and Microwaved Fish: Navigating the Dos and Don’ts of Workplace Culture. Now, Peter has worked as a communication consultant in the corporate world, and he’s also the creator of Advice from Someone Else’s Dad, which started as a blog and now includes a podcast and video series featuring, as the title suggests, advice from someone else’s dad. Peter, thank you for joining me.

Peter Yawitz: Well, thank you, Brett. It’s nice to be here.

PY: Well, I agree with you, I think it is valid for other people rather than just young professionals, but the whole idea of Advice from Someone Else’s Dad came from some of the work that I was doing naturally with some of my corporate clients.

One of the most fun things I get to do every year is to do new-hire training for a large number of people who are hired by big investment banks. And a couple of years ago, I had maybe 600 people in one session, and these were international young people. I talked about how to communicate at work and I was talking about some basic things that they needed to know. And then I said, “Let’s just open it up for questions; anything that anyone would want to know that no one has told you?”

And I guess at that point, since my seminars are pretty much — they’re full of information, but I try to keep it light and funny, people felt comfortable with me. So some of the questions, initially threw me because I didn’t expect them. And the first one that came up was, “Well, can I ask you a question, what happens when you are with your boss and the boss follows you into the restroom and is in the adjacent stall and continues to talk to you, what do you have to do?” And my thought was, well, you know, sure he wouldn’t ask this question if he didn’t want to know the answer, and I just said, “All right, well let me just tell you something, you’re under no obligation (laughter) to continue a conversation, you can just say, ‘Hey, can you just give me a moment and then we’ll talk a little bit later?’” And that opened it up and people started to laugh and they asked more questions like that.

The next one I think was, “What do you do when you are talking to somebody at work and that person is totally hot?” And, of course, you know with 600 people who are all in their 20s, they just thought this was the funniest thing in the world. And, then the answer really is, you know, I hadn’t prepared for this. I said, “Listen, we’re all human, these things happen. And you know what? These feelings are not going to go away, but you have to learn that you have to compartmentalize what’s professional and what’s not professional, and increase your listening skills to be able to block out some of the stuff that’s distracting, no matter what it is.” So I started getting more of those questions and I wrote them down and that eventually became the blog and that became Advice from Someone Else’s Dad. So that’s really how that came about.

BT: I imagine that both in your professional work and also as an author you’re sometimes giving advice that people don’t want to hear. (laughter) What is your approach when you know that you’re giving advice that may be difficult to follow?

PY: I think the advice that people don’t want to hear is where I’m recommending they do something that’s out of their comfort zone. And that is often something like, “You know what, I know it’s really comfortable for you to just text your manager and — or text a client, but you know what, get off your ass and talk to somebody.” (laughter) You know, it’s really important to have face-to-face meetings and I know that’s hard for you, and I know that’s something you haven’t done in college, but it’s really going to make a big difference in terms of your relationship with people, but also in getting information.

I get a lot of people who are reluctant to do that, even though they say, “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, I know you say that, but I’m not sure I want to do it.” But I might get a little pushback on that, but I think they — it’s just because it’s out of their comfort zone.

BT: I suppose that’s a big part of navigating the workplace is kind of figuring out not just what’s appropriate, but what you need to do that may be outside of your comfort zone.

PY: Yeah, I think it’s really true. And I don’t want anyone to think, well, this is only for introverts because introverts are the ones who are shyer and want to just sit quietly by their computer. But it’s really for everyone. And I’ve got to say that part of it is for managers.

I find one of the biggest troubles at work, especially for young people, is the lack of communication and lack of validation that they’ve gotten something right. They think it shows a sign of weakness that they didn’t quote, “get it,” the first time. And, so they might go off trying to do a task where they’re not really sure what they’re supposed to being doing, but they think they do and that’s going to cause more steps down the line where they’re going to have to go back and the manager said, “Well, this is not exactly what I wanted.” So an important skill for everyone to master is, for the young people to say, “I just want to make sure I got this right,” and regurgitate whatever notes they’ve written, and for the manager to make sure, if that person is not doing that, the manager says, “All right, let me hear back from you what you think the next step should be.”

So it really is for managers, too, who need to understand that maybe they’re not crystal-clear about things and it really is that two-way street.

BT: Let’s start at the beginning. Every workplace is different, every office environment. But what are some of the sort of universal dos and don’ts if you’re a new hire or a new college graduate? What are some of the universal dos and don’ts of being a good colleague and being a good employee?

PY: Well, I think, first of all, you should understand what the corporate culture is before you get there and know what your place is and how people get along and how people socialize and how people don’t socialize. So I think there is kind of a level-set, to use a bad cliché, because I hate using clichés, but it just happened to fly right out of my mouth. I think it’s important for them to understand what is expected of them in the very beginning. But also to ask around to see, “Is this how we typically do lunch here?” “If I’m asked to do something, what is the formality or lack of formality that I’m supposed to use in an email?”

So just really get a sense that you’re not coming out as a complete fish out of water. Sometimes people will train you, but I think it’s just important to get some advice from people who have been there, to say is this the appropriate way of doing things? And if you’re not even sure from a colleague, just certainly ask someone. Find a mentor, find a manager who can help you navigate through some of the stuff that makes you uncomfortable.

BT: Going back to clichés and jargon, you do write about that and I suppose that makes sense, given your background in communication. Why is it so bad to slip into business-speak and how does one avoid that?

PY: I’m not totally anti-business-speak, the problem is when people use phrases that really don’t mean anything. And then the young people use it because the senior people are using it and they want to suck up to the senior people.

I think my first job out of business school I was working with a team and my boss loved to use the phrase, “De minimis,” which just means “a little bit.” And, you know, it’s a “De minimis improvement this month in ... this market.” And then the suck-ups would say, “Well, you know what, I think de minimis improvement here, too.” And I’d just want to bang my head against the table, like, why can’t everyone just say plain speaking, like, just a little bit? Why do you have to use de minimis? Why can’t you use something simple?

And another funny one is that, when people use this phrase, “Go after the low-hanging fruit,” which people use in business to mean “Go for the easy, attainable business.” And it’s just —if you want to use it, fine. Just know that it’s overused. When I’ve talked to people who have grown up on farms, they say, “The problem with going after the low-hanging fruit is that fruit has usually been gnawed on by animals, so it’s the worst stuff that you want to take.” So, I’m not going to correct anyone’s “We have to go with low-hanging fruit,” and I’m not going to say, “You made a mistake, that’s not what you really mean, because that’s all rotten fruit.” (laughter)

Actually, you know, some of the ones that drive me crazy are the ones that are grammatically incorrect. One of them, I’ve heard recently is, “Let’s action this.” And, you know, I just go into convulsions when I hear that and I want to say, “Listen, everybody, action is not now, nor will it ever be a verb.” You can take action, you can act upon something, but you can’t action something. I can’t action my foot. I can’t action piece of paper. It just doesn’t work that way.

BT: On that same note, probably a not good idea to come into a new job and start correcting people’s grammar, but in your role, I guess you can pull it off.

PY: You know, when I talk to other people, they say, “I work with someone — or my boss says this bad grammar, and I just want to correct, but I know I can’t.” And I say, “That’s what’s great about being a consultant, I can say whatever I want to people.” (laughter) And I’m still going to get paid as long as I’m not insulting them. I just want to say, “You know what, let me just tell you, just remind you about this, how to say this, because I don’t want anyone to think less of you if you’re not saying it or writing it correctly.”

I live by three rules: I live by the laws of the land, and the Constitution, by the way. Number two is the Golden Rule, I believe that you should treat others the way you want them to treat you. And the third is the rules of grammar. But that’s just me.

BT: (laughter) On a related note, when people aren’t meeting face-to-face or speaking on the phone, they’re going to be communicating by email or messaging platforms like Slack. What are the key adjustments that young folks need to make when they start composing written communication in an office environment versus personal or social communication?

PY: Well, I think that’s a good question, and again the first answer, I have to say, is it really depends on the context of the company. If it’s a very informal company and people use Slack all the time — and I think it’s a great way of communicating, that’s fine. Just remember that — actually, I’m back to this concept of rules. I don’t have another rule, but I do call this the “One Email Rule” or “One Email Guideline,” is don’t send an email where the next email’s going to come back saying, “I don’t get it,” or “What?” Or “When?” Or “Why?” So I would just be complete about how you email something. And when you text, you tend to not put a lot of information in, and not to say that you have to do an email with tons of information. If you have tons of information, you should lay it out in enumerated form, but I just don’t want to say something like, “I think it’s a very bad idea to meet with Joe,” and hit send. Because the email comes right back and says, “Why?” So that violates the “One Email Rule.”

Also, saying something like “a bad idea” is such a negative way of doing things. It’s easy to criticize. “That’s a bad idea.” “I hate your shirt, Brett.” I can’t even see you, but I know I don’t like it. “I hate your shirt, Brett.” It’s like, maybe the shirt — “I think the shirt might be more appropriate in a party situation. At work, perhaps you might want to wear a collared shirt.” (laughter)

So saying, “This is a bad idea to meet with Joe,” you could say, “I don’t think we should meet with Joe until we complete our first round of the project”; [that] would get you around that violation of the “One Email Rule.”

What kind of shirt are you wearing, Brett?

BT: (laughter) It does have a collar, yes.

PY: Oh, I’m glad.

BT: Very plain, blue shirt. I did not wear my football jersey to work today.

PY: Hey, on a podcast you can wear anything. Someone actually emailed me the other day to ask if I’d be on her podcast and she said, “And you can wear flip-flops, because you can’t see it.”

BT: (laughter) The communication advice: Does the same sort of thing apply for social media? I mean, how do you suggest people manage their Twitter accounts or their Instagram? Can you continue to rant and rave about the New York Knicks? And post a bunch of cat memes? Or do you have to kind of switch to private accounts when you’re starting off?

PY: I’m looking — @bretttomlinson now —

BT: Oh, no.

PY: There’s your cat. Oh yeah. Very cute. I like what you had for dinner last night. I think you’re — I’m not a big social media guy, but I think it’s fine if you want to have it on your private account, but make it private. Or make it personal. So don’t include anything about work. Don’t post anything about work. Don’t say anything about your boss or this great event you had at work. Because that great event at work was sponsored by your job, and let your job post about that. I just think that social media should be — if you have social media make an account — if you’re an entrepreneur, make an account that is business and then if you want to share your cat memes, do it on your own private thing, and make it private and share it with your friends. And maybe they’ll share them back with you and you can just have a big, old cat day.

But I — I’ve had to ramp up my social media just because my audience is younger and they tend to look at Instagram. But I don’t want — I want to show that there’s something fun and informative about things that I put on my @someoneelsesdad account. So I will do some funny memes, but there’s usually some lesson as part of it. I don’t want to just do little platitudes or, you know, “Today is the best day of the rest of your life,” because even though it might be, you know, it’s just not me. I mean, I’m a nice guy and everything, I want you to think that I (laughter) recommend nice things, but mine is a little bit, I don’t know, more accessible and fun, I would hope.

BT: It sounds like the same idea of sort of compartmentalizing that you mentioned.

PY: Yeah. I mean, I just — also I don’t find my life interesting enough for anyone to care what I had for dinner last night. (laughter) But do you want to know what I had for dinner last night?

BT: Not particularly. No offense. You mentioned meeting with new hires and their concerns. What do managers get wrong about this generation of folks coming into the workforce? What do they need to do a better job of, in sort of helping folks along?

PY: I think that’s a great question, and I’ll just say, personally, the other night I was at a dinner party on New Year’s, and a lot of old fogies like me, you know, “OK Boomer.” A bunch of people were just saying, “You know all these young people want this, and they want shorter hours, and they want to have a better life...” And for me, who just wrote this book, and also as a friend, I wanted to say, “You know —” and they just kept complaining.

And I really, as I said before, I think it’s something that previous generations had to adapt to, to the next generation, all the way through, in terms of new technology, in terms of how people get work done. And just because this new generation is so much more tech-savvy than the previous generation, and also social-media-savvy, meaning that they see what their friends are doing, it makes them stand up for themselves a little bit more about, “This is the kind of life that I want, the kind of work that I want.” And I just think that the managers have to recognize, all right, I need work done, I’m just not gonna agree to every demand that you have, but perhaps there are different ways of working. And perhaps you can demonstrate trust by saying, “This is what our goal is together. We have to achieve this for a project or for a client, or we’re working on, toward this goal. So this is what we are doing collectively. I don’t care how you get there, but these are the tasks that I need you to do by a certain date so that’ll help me.” Show a rationale of why I’m doing something and their role in it.

And I think young people, what I’ve heard and what I’ve experienced is that they want to feel that they’re a part of something bigger. They don’t want to be just task rabbits. And I just think that all my friends who were complaining the other day — listen, they can complain, but what are they doing to change? I think my job is to work with the young people to say, “All right, there’s certain conventions about working with the old folks.” But the old folks have to think about, “All right, what skills do they have that might help us?” And make sure that they understand what the big picture is and their part of it.

BT: I think our listeners are getting a nice sampling of the topics in your book and I wanted to ask about one of the more serious subjects, which is difficult conversations that are a natural part of your career. Things like, at some point you may want to ask for a raise, or a promotion, and you may be going into that conversation without a lot of information about what your colleagues are being paid and how your salary compares, things like that. How do you suggest people prepare for that process and kind of get into the right mindset to have those conversations?

PY: Also, it depends on your organization. If you’re working for a large company that has very specific lock-step dates and metrics about when you’re going to get a promotion or a raise, I think you have to respect that. I even remember, I mean, I’m not evading your question, but I remember my first job, I found out that I was the lowest-paid associate, because I was shocked that people actually started to compare. And I went into my boss and I said that I just found out that I’m the doing the same work, and maybe I’m a year younger than some of the other people, but I’m the lowest-paid one. And he said, “Thank you for telling me that information. It’s something that I’ll take into account when we do our reviews every six months.” And I have to say that I respected that because there are some rules in place and they had to follow through on that.

The other thing that I found now if I’m talking to young people, as I said, I was a little bit shocked that people were sharing how much money they made. Now, people know very quickly how much other people are making. People just ask. Not that they’re posting it on social media, but I think friends know what other people are making, and certainly colleagues would, too. So I think that if there is a rationale for you to feel that your raise is warranted because you are doing something or adding to the bottom line or really going beyond what you feel you are being paid for, I think it is not a bad idea to ask for a raise in a company that might accept that, but I would certainly have enough backup to prove that. Rather than just saying, “Well, I feel I need a raise.” Or because your parents are saying, “You should be paid more money,” and that, you know, gives you an incentive to want to ask.

I think it’s important to write down some things that you’ve done, how you’ve saved the company money, how you’ve made the company money, what you’ve done to make things more efficient. And rather than saying, “I know my friend is making this,” there are websites that tell you where you should be. And if you think legitimately you were underpaid by those types of metrics or those standards, and you feel that you have done enough and haven’t been compensated for it, I think it’s a fair way of doing it. But I would never do it in — I would have your preparation in writing, but I would want to make sure that you had a face-to-face conversation with your manager for that.

BT: Thinking back to your own experience when you were coming out of Princeton and beginning your first job, what’s the advice that you wish someone had given you back then?

PY: Well, I think, advice I give a lot of people is, “Remember, this is not going to be your only job.” The first job you’re getting, it does not define you. This does not mean you’re going to be stuck in this industry for the rest of your life. So, develop skills, learn what you can from it, and not to take advantage of anybody, but recognize that if you are unhappy, all right, this is just a part of a journey that you’re going through. Stick it out, for a while, and develop skills because you’re always going to develop something that’s going to help you in the next job.

This actually comes up a lot, is when people want to change sectors or change jobs entirely, and people say, “Well, I could never do that because I’ve only worked in retail.” But what skills have you developed working in retail that you could transfer to consulting, for instance? Well, is it good listening skills? Is it good analytical skills? So you want to be able to sell some of those successes you’ve had based on the skills that you’ve developed that you can translate to a different type of job. Just because you worked behind the counter at Sephora doesn’t mean that you’re stuck selling perfume for the rest of your life. Or makeup. It means that you have good customer-service skills, or you’re able to demonstrate how you were able to increase sales by understanding a customer.

So just know that, even though you might be unhappy, there are things that you are definitely learning about. And, in fact, maybe it’s also just learning about the environment that you’re in. And I don’t want to be in this environment, I don’t want to work for a big company, or I don’t want to be in a two-person organization. So I guess that’s my long winded way of saying, don’t be so very focused on the first couple of years because life is long.

BT: Good advice.

PY: What do you start doing, Brett?

BT: I started in consulting, for what is now Accenture. Many years ago.

PY: No, that’s great. But I’ll tell you another thing —

BT: It was not a great fit for me, but it is for many people.

PY: Yeah, no, exactly. And it’s the same with my very many first jobs, before I went to business school because I thought I was just at a bunch of dead-end jobs. But on my podcast, I’ve interviewed a couple of people who are in not-for-profits, and I’ve asked, “What skills are you looking for?” Because I think, again, a lot of young people come out of college and they want to do something that is for the betterment of the world. And one guy in particular, he’s actually a Princeton grad, he said, “I just find that the people who have grown up in nonprofits,” and he’s, you know, this is over-generalization, he said they are lacking some basic skills that people develop by working for a place like Accenture. They can’t write very well, they don’t do well in project management, so he said, “I look to hire people who have been in the private sector for a while, who’ve developed some great skills because now I can rely on them to get work done.”

So, again, even if you’re coming out of college and you know, I want to do something that’s good, I don’t want to say, “Suck it up and work for a consulting firm,” but I mean, you could be an example, too, Brett. I mean you worked for a consulting firm, you knew it wasn’t right for you, but I’m sure you developed some skills that you found have been valuable for you in other parts of your career.

BT: Definitely. Definitely have.

PY: Like talking to me. (laughter) You sound so professional.

BT: I do my best. (laughter) Well, Peter, it’s been a pleasure speaking with you. Thank you so much.

PY: Well, thank you, Brett. It’s been a pleasure speaking to you and to the larger Princeton community.

BT: Peter Yawitz’s book is called Flip-Flops and Microwaved Fish: Navigating the Dos and Don’ts of Workplace Culture. If you’ve enjoyed this podcast, please subscribe. You can find us by searching for “Princeton Alumni Weekly” on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, or SoundCloud. You can also find transcripts of all podcast episodes on our website, paw.princeton.edu. This episode was recorded by Daniel Kearns at the Princeton Broadcast Studio. The music is licensed from FirstCom Music.

Paw in print

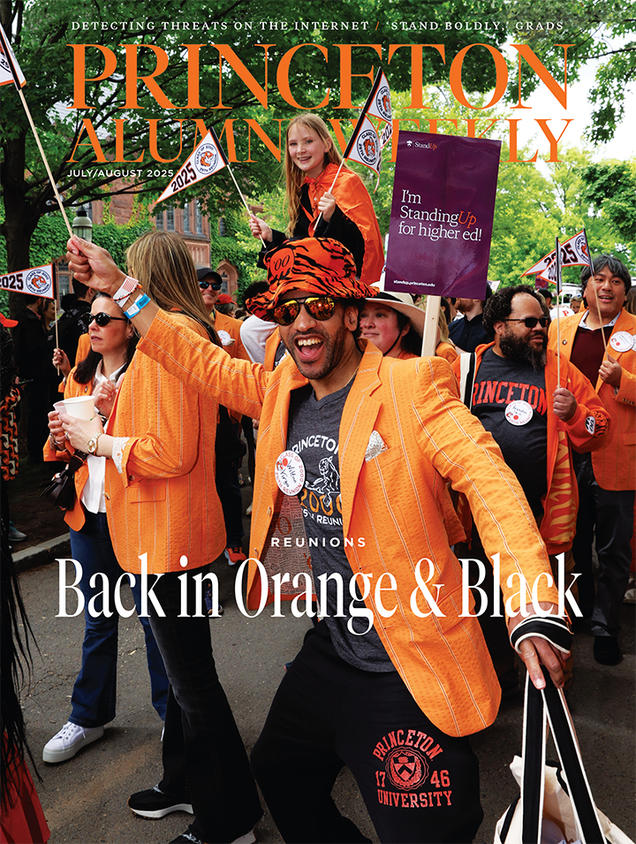

July 2025

On the cover: Wilton Virgo ’00 and his classmates celebrate during the P-rade.

0 Responses