PAWcast: Professor Alan Krueger on ‘Rockonomics’

An economist’s view of streaming music, secondary ticket markets, and more

Economics professor Alan Krueger — former chairman of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers — tells PAW’s Allie Wenner about his research on the economics of the music industry, including his opinions about the secondary market for concert tickets, how online streaming has reversed the downward trend in revenue for recordings, and why he thinks Taylor Swift is an “economic genius.”

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

This is part of a monthly series of interviews with alumni, faculty, and students.

TRANSCRIPT

AW: You’re listening to the PAWcast. I’m Allie Wenner, and I’m here with economics professor Alan Krueger. He has published widely on topics such as the economics of education, unemployment, labor demand, and income distribution, to name a few. He also served as chairman of former president Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, and he was a member of the cabinet from 2011 to 2013. But he’s back on campus now, and this fall, he’s teaching a course here at Princeton on the economics of music. So welcome, Alan, and thank you for being here today.

AK: Thanks for having me.

AW: Now I know you’ve been doing research on the economics of the music industry for quite some time now. But I’m wondering how you got interested in this area of research. And what sorts of things have you been focusing on recently, relating to this topic?

AK: I’ve actually worked on “rockonomics,” on the economics of music, for almost 20 years. Back in 2001, I promised my father I would take him to the Super Bowl, if the Giants made it. And the Giants did indeed make it to the Super Bowl, so we went. And I wrote an article in The New York Times about the economics of Super Bowl tickets. Shortly afterwards, I was invited to be the keynote speaker, by Pollstar Magazine, at their concert convention. And I explained to Gary Bongiovanni, who invited me, that I knew absolutely nothing about concerts. And he said, “Don’t worry. We can help you. We have data on over a quarter of a million concert records. We collect the data from the venues.” So he provided me with a database, and I had great fun, and I learned a lot preparing for that talk.

I looked at inequality among musicians. I looked at the increasing concentration in the industry. And I gave a presentation the likes of which I think the concert promotors and stagehands had never seen before, where I showed them Gini coefficients and Laurent curves and Herfindahl indexes. I tried to explain it all. And I got a very nice reaction to that work.

The vice president of Ticketmaster asked if there was anything they could do to help me. And I told him that, unlike the Super Bowl, where I interviewed fans and I found out how many bought tickets on the secondary market, how much they paid, that type of thing, I don’t know that for concerts. So he arranged for me to bring a dozen students from Princeton to a Bruce Springsteen concert in Philadelphia, and then a U2 concert at Madison Square Garden, where we conducted interviews with the fans. And then I did this for 30 other concerts, where I didn’t go myself but I worked with the ushers to conduct the survey and collect the data for us.

AW: So what kinds of things were you asking those fans about?

AK: We asked a similar set of questions that we asked at the Super Bowl. We asked how did they buy their ticket, did they buy them from a scalpe? As work progressed in this area, the whole scalper market moved online. So we asked whether they bought tickets from eBay or StubHub, some of the other places where you can buy in the secondary market. How much they paid for their ticket. I asked a question, which is related to work in behavioral economics, which is, suppose you didn’t have a ticket. Would you have been willing to pay $500 for your ticket? Suppose somebody offered you $500 for your ticket. Would you sell it? And we saw a remarkable asymmetry, same thing I found at the Super Bowl, that once people have a ticket, they treat it like it’s more valuable than if they didn’t have it. And that’s been called the endowment effect in behavioral economics. So those were the types of questions that we were after.

AW: That’s really interesting, and I’m really glad you brought up ticket prices and the secondary market. How would you describe the current state of the market for concert tickets? For example, is it better to be an artist or a scalper or a promoter right now? Who’s making money here, and how are they doing it?

AK: It’s actually quite hard to make money in the music industry. If you had your choice, you’d like to be Bruce Springsteen or Taylor Swift. But it’s not easy to be a superstar in the music industry. There’s an awful lot of competition. And the music industry is very much a superstar industry. A small number of performers bring home the lion’s share of the money.

The top 1 percent of performers now take in about 60 percent of all of the income in the music industry. And that’s up from about 40 percent 25 years ago. So one of the reasons that I found this an attractive economic topic to study is because this is truly a superstar market. The promoters tend to be competitive. LiveNation is the largest promoter, and they have a lot of market power. So that’s one aspect of the industry that’s changed. But their costs are also very high. So I think people should go into the music industry if they’re passionate about music, if they can’t imagine themselves doing anything else. If they are interested in making a lot of money, they’re better off going into finance.

AW: And I’m glad you brought up LiveNation, because I wanted to ask you about them. They are the biggest promoter in the country, and they have been for some time now. The New York Times reported that they’re in charge of selling tickets for, I think, 80 out of the top 100 arenas in the U.S. Should we be worried about a possible monopoly situation with this company, and what implications could that have on the concert ticket market?

AK: One of the original hypotheses I had was that concert prices have been growing so rapidly because of increased concentration in promotion. And just to put the numbers in perspective, concert prices have grown faster than medical-care inflation, almost as fast as college tuition. And you have to wonder why.

So one of my hypotheses was that this was being driven by SFX, which was a predecessor to LiveNation, and then LiveNation, which is by far the largest promoter. On the other hand, when I look at other countries where LiveNation is not as large a player, you see a similar trend in terms of prices rising. And I think the main driver for the increase in ticket prices is that historically, bands made money by selling recordings. Remember those old vinyl albums? And from going on tour. They would go on tour to promote albums, to sell more albums. But after Napster and rampant piracy and file-sharing, revenues from selling recordings plummeted. And the money that the record labels and the artists were taking in fell by more than half from 2000 until 2015.

So the record industry plunged. The artists started to look at concerts as more of a profit center. And I think historically, they had much more pricing power than they were willing to use. They were happy to sell out immediately, instantly — have a lot more demand than they had seats available for without raising prices — because that helped them to sell more records. But now that they’re making less money from selling records, they started to view concerts as more of a profit center. And that led them to raise concert-ticket prices.

AW: Interesting. I want to ask you about companies like StubHub, which allow consumers to re-sell their tickets for whatever price they choose on the secondary market. What relation do companies like that have with this changing economic model? Do you think they’re necessary? And do they make it easier for scalpers to do what they do?

AK: Well, my views have changed, actually, on the secondary market. And I think it’s more complicated than simple economics suggests. So I do think that the major reason for having a secondary market is that tickets are mispriced to begin with. They’re priced too low, especially for their best seats. And that gives an arbitrage opportunity, where the scalpers can buy those tickets and then re-sell them at a higher price and keep the difference.

There are other reasons for the secondary market. Peoples’ plans may change. And I think this is also related to the way tickets are distributed in the primary market. It would make some sense for the primary market distributors, like Ticketmaster, to hold some tickets back, to release them more slowly over time. Sometimes, that’s called slow-ticketing. And because the tickets are not distributed in an optimal way in the primary market, that leads to the secondary market.

Now, you have to go back a step and say well, why were they charging a price below the equilibrium market price? And often, it’s because the performers don’t want to gouge their fans. They want to charge what they think is a reasonable price. So Bruce Springsteen and others keep their tickets below the market price because they want to give their fans a lot of value. Now, the irony is that the scalpers will often swoop in and get the benefit of keeping the prices low. So I like what Bruce Springsteen has been doing more recently, where he has the verified-fan program, where only registered fans can buy tickets. You can re-sell them, but you can only re-sell them to a verified fan. And the research that’s been done in this area, not just by me but by Alan Sorenson at University of Wisconsin, Phil Leslie, and others, find that the scalpers were getting most of the value from the tickets being mispriced, that the fans had tougher competition to get tickets. So I do think there’s a legitimate public policy interest in trying to prohibit the secondary market if the performers want the benefit to go to their fans. I think a better way of distributing the tickets is to have a program like verified fan, to have slow-ticketing, where the tickets are released more gradually over time. I think if performers want to give back value to their fans, they can donate money. And some do that.

The other thing I was going to mention is a model of Garth Brooks, who had a very interesting idea for his last tour. He wanted to keep his prices affordable and low. I think they were around $60 a ticket. Where, if he gave a relatively small number of shows, I’m sure he could have charged $150, $200 a ticket. But what he did, since there was so much demand at $60 a ticket, is he kept adding shows. And he essentially shut out the secondary market because you couldn’t charge $100, $200 a ticket because he kept adding shows. So someone could always buy a ticket on the primary market.

AW: So there were enough tickets for everyone who wanted one.

AK: That’s right. He expanded supply. Now, it was tough on him. He actually provided I think more shows than may have been optimal in terms of maximizing his income. But he gave back the value to the fans by providing more shows.

AW: That’s really interesting. I hadn’t heard about that. Why don’t we see more artists doing things like this? Do they not know about this research? Do they not know what the best way to approach it would be?

AK: That’s a great question. I’ve had several managers say to me, “I wish you could talk to our artists and tell them that we’re not charging enough for the best seats.” It’s particularly the best seats, I think, that are under-priced and that we’re seeing re-selling. There’s a lot of concern about not selling out. Artists are a little worried that it’s an insult if they’re performing to a house that’s only half-full. And they don’t want to be criticized in social media as having gouged their fans. So I think that puts pressure on the artists. The technology has also improved to the point that something like verified fan is much more feasible. So I think we’re going to see more experimentation and more use of these models in the future.

AW: Very interesting, Alan. And one last question relating to ticket buying and the market. So something that I’ve noticed in recent years is that companies such as Ticketmaster will charge these service fees on top of what the regular concert ticket set price would be. And it’s not really clear what they’re for. And maybe I’m crazy, but I swear these fees are getting higher every year. So Alan, do you know what these fees are and why they keep getting higher?

AK: Excellent question. So the fees are part of the same story. The fees often go back to the venue, sometimes go back to the performers. The fees are not the actual cost of having to process the tickets. That’s a very small part of the fee. Ticketmaster is sort of a heat shield. It gets the blame. It takes the heat for prices going up, for the fees being so high. But the fees will often go back, or a portion of them, to the venue, if the venue has an exclusive arrangement with Ticketmaster. Or it could also go to the artist, if the artist and their manager negotiated for that.

AW: OK. And question for you. What was the last concert that you saw, and how’d you get your tickets for that?

AK: Last concert that I saw, I went to see, I went to Central Park to a free concert. And I saw Andra Day, and The Weeknd, and Big Sean. It was a long day. Alessia Cara. How did I get my tickets? I had done some work with one of the promoters, and that was part of the compensation for the work that I had done.

AW: Very nice. Pretty good deal, it sounds like.

AK: It was. It was a very fun afternoon.

AW: Very nice. And Alan, I want to switch gears a little bit here. I know that you were involved with a survey that came out about a month ago. It was released by the Music Industry Research Association and Princeton Survey Research Center. And it kind of looked into the challenges and opportunities that musicians face today. So I’m wondering if you could talk about some of the most interesting things, at least in your opinion, that you and your colleagues discovered in preparing that survey.

AK: Thanks for asking. One of the things I have done as I’ve thrown myself back into research on the music industry is to form the Music Industry Research Association, a nonprofit group. And we hold an annual conference. There are other academics who do research on the music industry. I’ve found it the best way to teach about economics to students, also a very good way to learn about how the economy works.

So we’ve been trying to organize events where people from the industry can meet with academics. We can share ideas, share our research. And at our first meeting, there was a lot of frustration on the part of academics that it’s very difficult to get data on the music industry. There’s a lack of transparency, which I think is a big problem in the industry. And I also came to the realization that the group that’s least well-represented is musicians. So we decided that we would do an annual survey on musicians to try to learn about their challenges and what it is they like about their job. Did this together with the Princeton Survey Research Center. This is very much a Princeton project. Ed Freeland, who is the assistant director of the survey center, worked with a class of students to help design a questionnaire. The questionnaire, I think, was excellent. And we probed very deeply about the lives of musicians, both their work and their lives. And we were careful to ask questions that have been asked in other national surveys so we can benchmark musicians against the population as a whole.

We discovered that musicians face a great many challenges. Their income is low. In our survey, the median musician only earned about $35,000 a year, which is slightly above the median musician nationwide. They faced a wide range of mental health problems. About half of the musicians felt depressed, anxiety was common. Drug use was common, about three times that of the population as a whole. So we found lots and lots of challenges for musicians. We also found that they’re passionate about their work. They live to entertain others. They do this, I think, recognizing that they’re not going to get rich from being a musician, that they’re just pursuing their passion. So this was our first time doing this survey. We’re going to continue to do this in the future.

The environment, I think, is changing very rapidly for musicians, with streaming, with changes in social media. So we wanted to learn a little bit more about how they’re adapting in that environment, how they use social media, how they use streaming, what are their sources of income. The average musician earned income from three and a half different activities. Live performances was the top activity for earning income, but also recordings. Also giving music lessons was quite common. Performing at a church service, quite common. So we’re discovering more about the lives of musicians, and I think that will be beneficial both for the music industry going forward, as well as for research.

AW: Yes. And I want to go back to that stat you brought up about the median income for the professional musicians last year, with $35,000. How does this compare to what musicians were making 10 or 20 years ago? Is it harder now for musicians to make money?

AK: The income of musicians has been pretty stagnant. And middle-class musicians have really been suffering. It’s hard to find a middle-class musician. It’s easy to make a little bit of money in music now with streaming. It’s hard to make a living from music.

AW: I’m glad you brought up streaming. I remember maybe four or five years ago, Taylor Swift made some big headlines when she actually pulled all her music from Spotify, claiming that she didn’t think that the way that they were paying the artists was fair. She didn’t think she was getting enough money. How difficult is it for artists to make money on streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music?

AK: First of all, I think Taylor Swift is an economic genius. She has made more money from concerts at her age than Madonna did at her age or Beyoncé or Lady Gaga, so she’s on a tremendous trajectory. And she has done this, I think, by making very good economic decisions. She was one of the first to use verified fan. She uses a loyalty program, where fans who buy merchandise or who listen to her videos and can demonstrate that they’re loyal fans have a higher chance of getting tickets when they’re released. And she has pursued a pretty innovative strategy when it comes to streaming, as well. She often holds her music back, sells digital downloads, sells CDs. And she is one of the leaders at selling albums for that reason. Yet she also comes off on the side of the angels by arguing that music has value. So I think she has helped the profession as a whole.

In terms of streaming, there’s now some optimism in the industry, which is very nice. And it’s the first time I’ve seen this, really, over the last 20 years, because music revenue has been growing over the last two years because of streaming. So I mentioned earlier that we saw a collapse of revenue for recordings from 2000 until 2015. Well, over the last two years, we’ve seen double-digit growth. And it’s because of growth of paid subscriptions for Spotify, for Amazon, for Apple Music. And I think the future is much brighter now because the streaming services have figured out a way to crowd out piracy.

AW: Wow, I had no idea. That’s really interesting. So do you predict that it will continue to grow that way? Are they doing things right in your eyes now?

AK: Well, I think we’re at the beginning of some rather dramatic disruption in the industry. I would like to see further changes when it comes to YouTube. YouTube is the number one source for people to listen to music in the U.S., and it pays out much less than Spotify or Apple or Amazon, which are competitors. And it’s partly a quirk of the way the copyright laws work, that YouTube is able to do that. Because it’s user-provided content. But I think we’re going to see continued growth in revenues in the music industry, not only in the U.S., but also around the world.

AW: Very interesting, Alan. And to bring things back to Princeton for a second, I want to talk about your new course, the “Economics of Music,” which you’re teaching this fall. Why teach a course on this stuff?

AK: Well, there’s no better way to teach economics than to discuss real-life applications, especially for the music industry.

Last year, I taught a freshman seminar on “Rockonomics,” with 16 students, and that was kind of a pilot test run. And this coming year, I’m going to teach a field course in the economics department, with a larger group of students. And I think this is a great way to apply economic concepts, because you can see it all in the music industry. You see supply and demand, and you see behavioral economics. You see considerations about fairness being a constraint on supply and demand, as we discussed when we talked about ticket pricing. So I call it supply and demand and all that jazz, because all that jazz is actually important for the way the market works. You see industrial concentration. We talked about Live Nation and the role of concentration. You see technological disruption with streaming. You see complementarities because the musicians perform both live concerts and they also try to sell recordings. So those are complementary products. So it’s a great way to teach a number of concepts from economics.

AW: Great. Well Alan, it was so great talking to you today. I really enjoyed our conversation. Thank you so much for coming in.

AK: Sure. Thank you, Allie.

AW: This interview was recorded at Princeton’s Broadcast Studio, with help from Daniel Kearns, and the music was licensed from FirstCom.com. And if you’ve enjoyed this podcast, we invite you to subscribe to Princeton Alumni Weekly podcasts in iTunes. We’ll be publishing more interviews all year long.

Paw in print

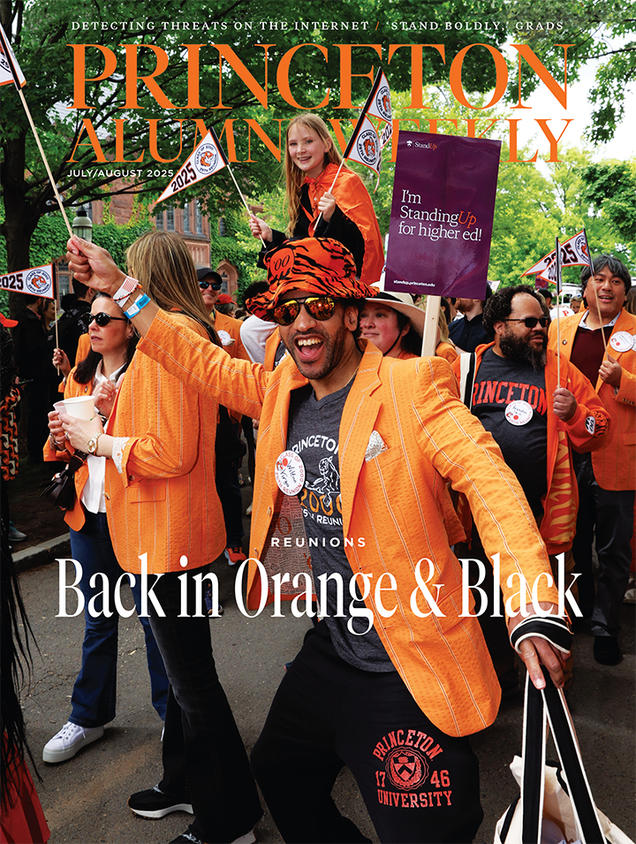

July 2025

On the cover: Wilton Virgo ’00 and his classmates celebrate during the P-rade.

1 Response

Norman Ravitch *62

6 Years AgoAre Artworks Valued Like Stocks?

I never thought about the economics of music performances and performers because I am one of those who have never got much past Mozart. But I do have a question about the Art World.

As the risk of being a philistine, I would like to say I cannot see how artworks are evaluated in monetary terms. The notion that an artist like Picasso could doodle on a paper napkin and have it be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not even more, makes me wonder if Art is not totally evaluated like stocks: not on the basis of intrinsic value but as a way of making money in a down or up market without any concern for intrinsic value. What makes my neighbor's painting worth $300 at the local art center and something by a long-dead Fleming worth $3,000,000? I confess I cannot say, because I think value is entirely in the mind and eye of the beholder and in the pocketbook of the investor -- with no other meaning. I would love some comments about this. I am not afraid of being considered an art philistine because I have a healthy respect for my own judgment in many, not all, things. Unlike Monsieur Jourdain, I know I am writing prose and don't feel excited by the discovery!