Q&A: Anthropologist Carolyn Rouse on the Art of Listening (and Tuning Out TV News)

PAW’s Q&A Podcast — October 2017

Anthropology professor Carolyn Rouse discusses her research trip to interview Donald Trump supporters in rural California, her “Trumplandia” project, the reasons why she hasn’t watched cable TV news this year, and how listening can be “a radical act.”

This is part of a new monthly series of interviews with alumni, faculty, and students. PAW podcasts are also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe.

TRANSCRIPT

Allie Wenner: I’m Allie Wenner, a writer for the Princeton Alumni Weekly. So, it’s safe to say that anthropology professor Carolyn Rouse has had an interesting year — for one thing, she hasn’t watched really any cable TV news since the presidential election last November. She also hasn’t been listening to NPR, or even reading the opinion section of The New York Times. For the past year or so, she’s really only been consuming news produced by people who she considers to be experts — like people who write for the New Yorker, and the hosts of the podcast “On the Media.” But for everything else news-related, Carolyn is turning to something called the “Trumplandia” project, which is a culmination of ethnographic evidence submitted by regular, everyday people. She started this project herself last November, and put out a call for submissions — writing, or photos, or really whatever people want to send her — asking people from around the world to share their take on anything relating to Donald Trump’s presidency.

But the thing is, not everybody liked this idea, in fact some saw it as an attack on President Trump and his policies. A conservative online news organization called Campus Reform wrote a story about Carolyn and Trumplandia, which went viral among conservative news outlets and prompted a slew of racist and bigoted submissions to the project. I caught up with Carolyn about a month after the media frenzy had died down to talk about her recent research trip to interview white Trump supporters in rural California, why she’s been so disappointed by the news media recently, and what its really like to cut yourself off from watching TV news — spoiler alert: it’s not as hard as you might think.

Carolyn Rouse: I’m a professor of anthropology, and I study race and inequality in different institutional domains since the ’90s in religion, medicine, development, and education.

I came up with Trumplandia after the presidential election of 2016, and I had this wonderful class, it was called “Anthropology Development,” and an incredible group of students who were really devastated by the elections for various reasons. And I had felt this incredible disappointment in journalism going up to that moment, because as an academic, even though I critique statistics; I’m an anthropologist, so we have these wonderful critiques about how people don’t capture a lot, and that’s why we love ethnography, I still wanted to believe that I could count on experts to explain what’s going on, because I don’t have the time and I don’t have the expertise to do that. And so, I was relying a lot on the media to help me, and I felt this incredible disappointment that I had counted on something that I already knew within my discipline needed critiquing. And so, I wanted to go back to ethnography; I wanted to know more about anthropology through ethnography. I wanted other people to try to tell me their stories. And the first stories — this is from the students — were extraordinary. The experience about having a conversation over Thanksgiving about — from, with their families about what just happened, and I had Chinese-American students, one whose mother was naturalized, the other who wasn’t, who voted for Trump, and she describes the scene where they’re driving in a car to, I think a restaurant, and how she just wants to ask her mom, you know, why she voted for Trump, and then being a brilliant ethnographer that she is, you know, she’s just describing, she just sat and listened to her mom, and she says, remember our friends who were beat up in LA who were American, but Chinese-American, from — by people who were Trump supporters who told them to get out of this country. And she just sort of leaves it there, and that’s the kind of — that’s what we do with ethnography, it’s, we don’t always try to make sense of what people say, and their commitments to these sorts of things. I think in the case of her mom, it was his “business savvy,” you know, which is what a lot of people, I guess, saw in Trump.

I don’t like to talk about these mainstream presses being written by — you know, these elitists who write — I don’t want to get involved in that, but what journalists don’t understand is, they have a particular set of concerns, and so they — the “so what” question, which, you say, in academia should drive your research, the “so what” question. In journalism there’s a “so what” question. If it’s off their radar, if they don’t see it as an interesting question, they’re not going to — and so I remember talking to editors of the New York Times, and I said — I was explaining how I kind of like the fact that — and of course, I wasn’t really paying much attention at this time, because I don’t — again, I’m not watching the news, but I heard that Sean Spicer brought in — people through Skype, journalists through Skype, is that –

AW: For one of his press briefings?

CR: Yeah, and one man asked about timber and well, you know, I don’t necessarily have a good feeling about what was probably said, but being in California, I was staying in a motel next to a timber mill. We would pass cars with, you know, trucks with timber. Timber is a real thing when you get out of New York or Washington DC, right? And so, how do you frame it in a way that makes readers in your audience — I mean, the concern is the audience, right? Well, who’s going to read a paper if they’re not interested in timber? So, but timber’s really important. We use it to build houses and buildings, and there’s an ecological element to it, right? So where are we with — I don’t even know. I don’t know where we are with respect to timber in terms of global warming, in terms of — right, the economy, nothing, right?

AW: I don’t know.

CR: And so that’s what slips out, and when they think these people aren’t reading their papers, or they’re not educated, or — well, you know, their concerns are not necessarily your concerns, and that’s another reason why I really want more people to submit to Trumplandia, because I want to hear voices from all over. I want that ethnographic moment, and that also requires people not, again, to just spew opinions. Ethnography means you’re not writing about yourself and your own opinions, you’re writing about somebody else. And so, that’s one of the struggles with editing and curating this, because you know, a lot of people don’t really get that. A lot of people want to just, you know, use this moment to state why they’re right, and somebody else is wrong.

AW: And so, I’m guessing, so based off kind of being let down by the media in the presidential election, you’ve chosen to not read any papers —

CR: No, I do.

AW: You do, so what is your media diet currently?

CR: Yeah, so the difference is, and I have had to do a little bit of — there were two days where I did watch, because I was just confused. One was the Scaramucci thing, which was — I couldn’t understand what was going on from reading the paper, and the next was the Charlottesville thing, where I thought, I kind of — I really wanted to see how these things were being framed. So those are two moments where I let this through, and of course I — you know, even writing this lecture for Free Speech, I had to, you know, look at some excerpts, you know, YouTube, free speech, and just kind of see what was being said.

AW: But a typical day for you, is —

CR: Yeah, I know, it’s not listening to NPR, that’s gone. It’s not watching MSNBC, that’s gone. It’s not, you know, really — I mean, Houston is, it’s still just a city to me, and I heard there was a lot of water. I saw some pictures of a lot of water.

AW: Yes.

CR: But I don’t have that same — you know, I was hearing, because I was in California right after, I was hearing — my interlocutors were screaming about Joel Osteen, which was interesting to hear about that story through other people, you know?

AW: And so that’s kind of what you’re trying to do with this Trumplandia project, correct?

AW: Yeah.

AW: So, to kind of fill that void that the media used to fill in terms of informing about the news, you’re asking people to submit stories and video?

CR: Yeah. It’s an attempt to learn about how people are seeing the world. But then, you know, it’s difficult because we live in a world now where you know, the comment sections have become just this strange space for people to just scream at other people. So, there’s a lot of that, and that’s hard. It makes me not want to look at anything, so. You know, I don’t want to read racism, I don’t want to have to. And I have to. Because, you know.

AW: So, a lot of responses, you’ve gotten?

CR: Yeah, some of them, yeah. So, you know, you just have to — anyway. So, it’s — we’ll work on it. We’re working on it. We’re trying to get it — trying to curate it and make it legible for other people. But I — you know, a lot of what I get is not even through the Trumplandia site anymore, it’s actually just talking to people.

AW: People will say racist things to you?

CR: People talk about — no, no, no, about the news, so. A lot of what I know about the news just comes from other people. People talk a lot about the news.

AW: And how do you — do you feel, you know, since you’ve started this project, less informed, or more informed than you were before you stopped watching the news?

CR: So, let me explain a little bit. I do — like, I’m willing to — I listen to investigative journalism. I listen to people I consider experts, so I do like, reveal, right? It’s about slow. I want slowness. I read the New Yorker. So, I’m not, not informed. What I don’t like about, in particular, cable news, or talk radio, is that they are trying to control your emotions in order to get you to feel a certain thing, in order to care in a certain way about that thing, and I don’t want people to tell me how I’m supposed to feel about, that I think has become the biggest thing for me. So, I’m happy to read about something that happened, but I don’t — I’m even having a hard time reading the op ed sections of any paper, and I feel like the op ed is actually starting to filter in the main part of the paper, so I have even a harder time reading the main parts of these papers as well. But — and also, another thing I’ve noted, even though mainstream press don’t want to admit this kind of desire on their part to see the person they were opposed to fail, which they won’t agree that they’re opposed to fail, there’s this constant framing where they want to make sure, you know, “We were right, see we were right,” you know? And I feel like we shouldn’t want the country to fail regardless of who’s in power, and he’s so predictable at this point, I mean maybe he’ll surprise us. So, I’m not actually really all that in interested in hearing, “Oh my God, he did,” you know, it’s really old at this point.

CR: And in the meantime, you know, they’re trying to pass another repeal with healthcare, which one of the things that I noted in my return to rural white America, or California, was that the Trump supporters wanted single-payer healthcare too. I mean there’s a proposal now in California, but the people I interviewed were so hurt by Obamacare, and not — before they were just devastated, and now they’re limited in how much they can earn, and K-Mart, all these corporations just completely take advantage of our government. I mean, it is welfare for K-Mart CEOs, this is just horrible. So, they cut these people’s hours just enough so that they don’t have to pay for their healthcare, and these people don’t make enough money, so they have to go to Medi-Cal, and then Medi-Cal does this thing where when you die you have to — your estate has to reimburse Medi-Cal, so the poor can’t even hand down their money to their kids because of this craziness. And you know, we’re talking about “death taxes?” I mean, this system is so rigged for the wealthy, and you see it, and you see it among Trump support— you see it among poor who have been Republicans all their life, and — so their emotional commitment to conservatism and Trump are the thing that fascinates me because, they know what they need, and it’s not what’s being offered, and so that’s what drives my research, and that fascinates me.

AW: Interesting, yeah, I have a couple more questions for you about the California stuff, but to go quickly back to the Trumplandia project, in terms of submissions, I mean, what’s been response so far? You’ve been doing it for almost a year now, right?

CR: Yeah, I mean it hasn’t been great, I have to admit. I mean, I was going to go out and ask my anthropology colleagues to ask their students to submit work and I have a number from my students in my “Race and Medicine” class, because — wonderful ethnographies of people’s experiences in healthcare. And then this year we have a course where students are going to go out and do ethnography, so it’s now building on coursework. We’re integrating coursework. But we got a bunch this summer after an article that came out in Campus Reform that, you know, sort of about Trumplandia. And those are the ones that I’m having a harder time with.

AW: Well I did want to ask you one question about those. I know you mentioned in your talk last week that a lot of them were just flat out bigoted and racist and like not helpful at all towards the ultimate goal of the project. But I mean, as you’re going through them, are there any that are actually kind of thought-provoking or that you feel —

CR: Absolutely, absolutely.

AW: — is there a silver lining to this whole media frenzy?

CR: Yeah, I mean, if I — at the end of the day, if I have, you know, 40 beautiful ethnographies that really say something, that’s great. And also, I have pieces from my own field work as well. So, there’s some beautiful, beautiful stuff.

AW: And when you say “ethnographies,” are these kind of like photos, or videos, what kind of physical —?

CR: No, written.

AW: Written things, OK, like testimonials?

CR: Yeah, yeah. And, yes. And I’m feeling — I mean, I’m just not — I’m not good at — I’m not good at social media, I’m not good at like — you know what I mean, so this is, me. For me this is difficult to — I’m not — I don’t do the whole self-promotion thing online, so I’m learning to do this, but I think once we get this curated, I think we’re — I’m in a better space to have this conversation because I think we’re now in a point where we can really sit and maybe people are more willing to pull away from the political discourses, and really like, you know, what does it mean to be in Florida, state that if the predictions hold, Miami will be gone, right? It’ll be underwater, and you know, what does it mean — you know, I want to know more about people’s commitments to challenging global warming from somebody who lives in a place like this where you’re starting to already see the powerful effects.

AW: And to just kind of go off of that. I mean, we’re talking about some really interesting things that have come out of the project, but I guess, to make it — kind of wrap it all up, like what is your biggest takeaway from this project so far?

CR: I don’t have a big takeaway, except to say, I still believe really, with my methods, and my discipline, that you know, we have theories, lovely theories, that are wonderful, that are documented through ethnographically, so through experiential data. But we are more than willing to put aside those theories when we’re in the field in order to capture what we are trying to capture, and as a result, we disrupt a lot of, even our own common sense about the way the world works or shouldn’t work, and we just aren’t conservative or liberal. Anthropology is — you know, most anthropologists are very progressive, but the best anthropology is just — it has nothing to do with any political group. And hopefully by the end, we will create some kind of document that may be a testament to the importance of ethnography as a part of media, and I think more and more people are doing that anyway. You know, there are more documentaries, sort of more ethnographic kind of documentaries, or more podcasts like you’re doing, where people are slowing down and just listening, and listening is a radical act. You know, it’s — and so, I actually am hopeful. And you know we had a class yesterday and we were talking about, you know, how this happened at the heels of an election for the first African American president, and you know, one student talked about a pendulum, another student talked about dialectics, and those are real things. You know, we’re learning from this moment. If we learn well from this moment, we’ll be in a better — or different, I should say, a different space, and again, I think at this point we’re civilizing this technology right now. And the Facebook, the challenge to Facebook in Germany right now I think is an example of how we’re going to be civilizing this technology, because this isn’t working. A free speech free-for-all is not working, but also what’s not working is the fact that people aren’t listening to these marginalized — not necessarily even marginalized, just people who are silenced in this loud, screaming, emotion-laden series of “conversations” that are taking place in the media, you know? We’ve lost that, the specificity of the local, and the nuances that you learn in the field. So that’s — so maybe at the end of the day I think, it wasn’t so much — I don’t think I’m learning as much as I thought I would, because I think that I’m attuned to what’s going in America because I interview people all the time. I think what it reminds me of is that I — we need to do a better job of explaining the value of ethnography and the art of listening, and trying to make sense of other people’s perspectives of the world.

AW: If you’d like to make a submission to the Trumplandia project, you can do so by visiting anthropology.princeton.edu/trumplandia-submissions. And for the record, Carolyn is asking everyone who wants to contribute to please avoid writing about their own opinions — for this project, she is just interested in collecting people’s observations and analyses of others.

If you’ve enjoyed this podcast, we invite you to subscribe in iTunes. We’ll be publishing more interviews, along with our PAW Tracks oral history podcast, all year long.

Paw in print

July 2025

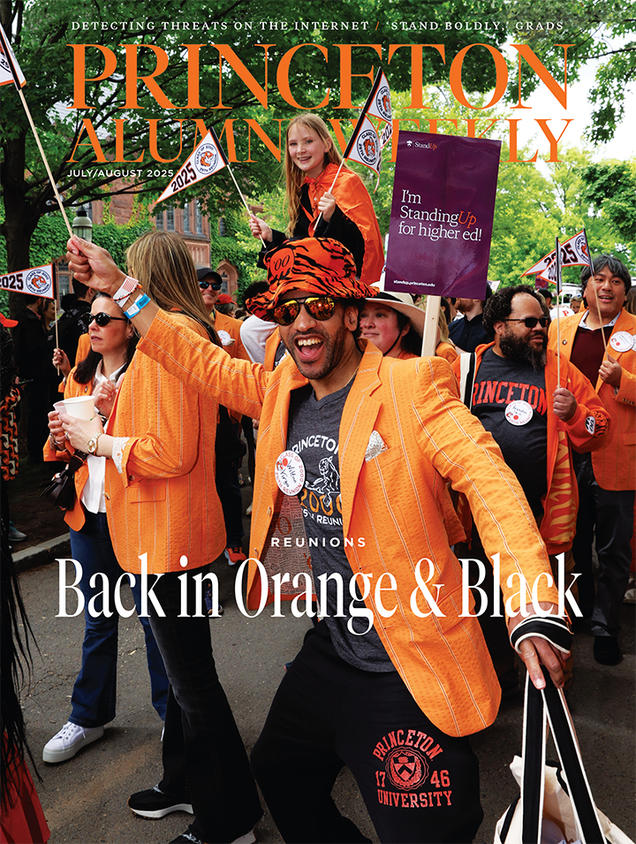

On the cover: Wilton Virgo ’00 and his classmates celebrate during the P-rade.

1 Response

Dan D’Menny

7 Years AgoEast Coast Elitist Gobbledygook

What a bunch of East Coast elitist gobbledygook. I would much rather listen to Charles Murray. Too bad Professor Rouse doesn't think Middlebury students should be allowed that choice.