Jack Bergland ’54 recalls Professor S. Roy Heath ’39 and the Class of 1954 Advisee Project — a four-year study that introduced Bergland to Heath and sparked a lifelong friendship.

PAW Tracks is also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

TRANSCRIPT:

For many students, a faculty adviser is someone you see a few times each semester, but if you’re fortunate, an adviser can become something more — a mentor, or even a lifelong friend. That was the case for Jack Bergland, Class of ’54, who spoke with PAW about Professor Roy Heath, Class of ’39, a clinical psychologist who met with 36 undergraduates during their four years at Princeton for a research study known as the Class of 1954 Advisee Project. Heath first met with the students before they began their freshman year.

It was the summer, about two or three weeks before we entered Princeton, and he came to my home in Baltimore. And so he talked to me a little bit, and of course it was all a little cloudy then. I couldn’t quite fathom what he was doing. But I was enthusiastic about being chosen.

Heath immediately had us in the fold. He was having interviews, he was having meetings with our groups. We were starting to know — Who’s this guy over here? Who’s this guy over here? And in that environment, friendships started to emerge. I mean we got familiar with guys who were totally different. You could sense it, I was different from another guy, another guy’s outlook on things was a lot different from mine, and there was a guy who was waiting on tables to pay his way through and here I was having my parents pay my way through, you see?

He started finding out about our interests and our parents and all of our background. He knew me better than my own mom and dad — let’s put it that way. And that’s an accumulation of four years. His interviews were — I enjoyed them. He knew what I loved, and I found out things that he loved. For example, my hobby is the old classic New Orleans jazz, and to the end of his life, he and I used to exchange jazz records.

I would often talk to Roy on my own, and he was wonderful. Never told you, really, what to do. He would make you realize, and then you would have to do it on your own.

At the same time, Heath was turning his observations into a model of student behavior, developing personality types for what would eventually become a book called The Reasonable Adventurer, published in 1964. There were the “non-committers,” type X; the “hustlers,” type Y; and the “plungers,” type Z — a type that, in Heath’s words, “desires excitement” and follows “the impulse of the moment.”

I was a “Z.” I was what he called the “roller boys” — we used to drive the man crazy, because I might be talking to you about your college, and the next sentence I’d be talking about the president of the United States. One time we’d come into an interview with him, we’d be in a bad mood. The next time, we’re happier than heck!

We were a type that wouldn’t get into Princeton today. A lot of us came in with the lowest SAT scores. And once we caught on a little bit, and found our niche, our group got more honors, more awards, played on more teams, and in the end, really, in some ways were the winners.

In this advisee project, where the word got out that he was kind of wet-nursing some of us through? That wasn’t true. He was trying to bring out our personality profile into the most … into the best way he could, in order to have us solve our own problems.

He didn’t get tenure here, and in the last year [of the project] he was told that that was it. And that really hurt him, it really hurt him, because this was his life, this project.

The reason for this I don’t know, but I think it’s because the administration didn’t like the idea that somebody was here helping all these students — and they weren’t just the guys in this project. There were many other students who would come to him because they needed him.

But here’s the attitude, and I can sum it up: If you were good enough to get into Princeton University, you should weather the storm, take care of yourself, and do well. There were many lonely kids here. There were kids far away from home. There were kids who were very anxious because everybody around them was just as good as they were. And they wondered if they fit in, they were homesick, and then that created anxiety but also depression.

And he – when he picked these kids up, he did something to help them. And they really needed it. I can think of one underclassman who was a couple years behind us who he saved his life by just meeting with him, two times a week on his own, maybe late at night. He was a good man.

After leaving Princeton, Heath went to Knox College in Illinois, while Bergland took a teaching job at St. George’s School in Rhode Island. His teaching career lasted just one year.

I decided there that I wanted to be a doctor. And so, I completely changed my “z” profile, in Dr. Heath’s mind. And when I decided to be a doctor, I really fouled him up. He said that’s the last thing I would have had you down for. What in the hell’s going on? But I reached a certain maturity, and you wouldn’t believe how I worked to get in and to stay in. In spite of being a “roller boy,” I still had that drive.

When I moved to Houston, he’d come down every year to have his physical by me, and I followed him right on to the very end. He had a terrible thing called a carcinoid tumor, which you can’t do much about. And I went to see him three days before he died. One of our [class] members, Nick Angell, and I decided to meet there more or less to see him and say goodbye. That was sad. And the one thing I did do — I brought back the jazz record he had lent me. He was really pleased about that.

Looking back, Bergland says, Heath was ahead of his time. Now, Princeton and its peers devote significant resources to advising and to mental health services, acknowledging that getting into college is just one step in an often difficult journey.

So it’s the idea that now you have available good psychologists or psychiatrists available to help these people because you can save lives and you can make a person’s life meaningful in college.

For Bergland, Roy Heath helped to make life more meaningful, during four years at Princeton and in the decades that followed.

This man was a great friend, and he personally helped me so much.

Paw in print

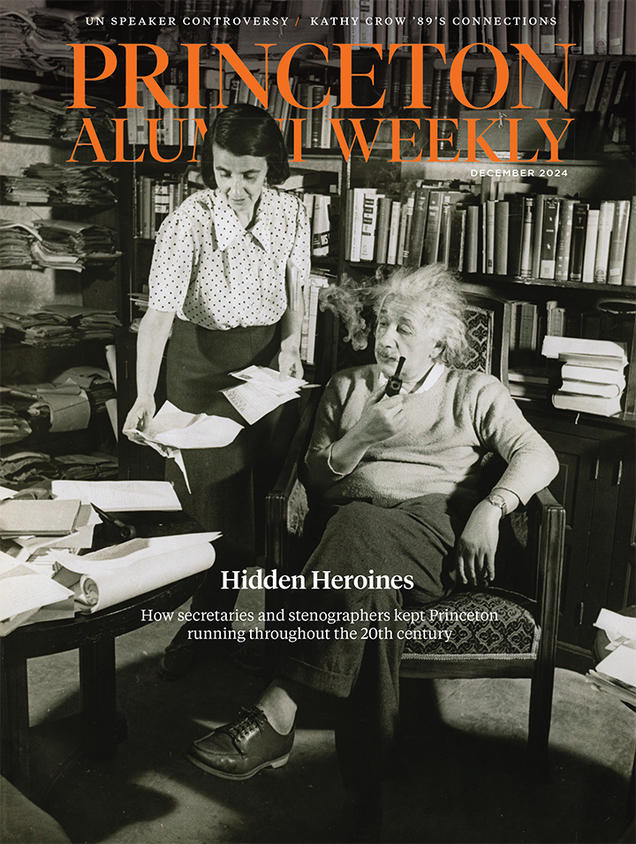

December 2024

Hidden heroines; U.N. speaker controversy; Kathy Crow ’89’s connections