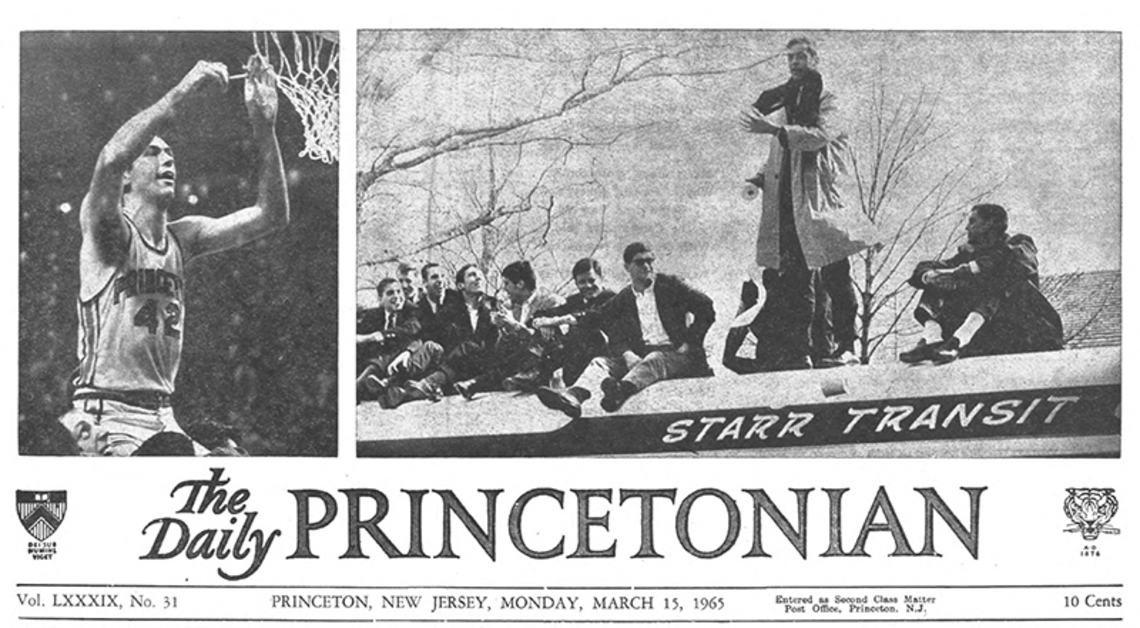

Rules of Motion: The 1964-65 Men’s Basketball Final Four Season (Part I)

PAW Tracks

Scouting Princeton’s 1964-65 men’s basketball team was a challenge — and not just because the lineup included All-American Bill Bradley ’65, an exceptional shooter and passer who rarely had an off night. Coach Butch Van Breda Kolff ’45 didn’t employ set plays, instead relying on rules of motion and offensive principles that made each possession unique. Members of the team talked with PAW about Van Breda Kolff, Bradley, and the qualities that would propel Princeton to the NCAA semifinals.

(Part 2 of this podcast will be published with PAW’s March 4 issue.)

PAW Tracks is also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

TRANSCRIPT:

In this episode of PAW Tracks, we turn back the clock to March 1965. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was marching for voting rights in Alabama, a Soviet cosmonaut was taking the first space walk, and far away from those front-page headlines, All-American Bill Bradley ’65 was leading Princeton basketball to new heights.

We’ll be exploring the Tigers’ remarkable postseason run on the podcast and in the print magazine next month. But first, we take a look at what made the team great, as told by its players.

Princeton’s coach, Butch Van Breda Kolff ’45, was 42 years old and a rising star in the coaching world. His approach focused less on set plays and more on motion, according to Bill Bradley.

Bill Bradley: It rewarded movement, passing, and it rewarded hitting the open shot.

Teammate Ed Hummer ’67:

Ed Hummer: It really was rules of motion. And so in a way a play was never busted. If something didn’t work, you were still moving.

Point guard Gary Walters ’67:

Gary Walters: And it was all read the defense stuff. Spacing, concepts, abstract expressionism.

We were taught concepts: Pass and cut, move, if they overplay, go back door, understand your spacing. But even more so, if you look at the teams — you look at ’65, you look at ’66, and then my senior year, ’67 — just look at how much we scored. We would fast break all the time. Fortunately we had the pieces in place where we could do that.

The 1964-65 team averaged just under 80 points per game and topped 100 points four times, including twice in the NCAA Tournament.

Bradley: I don’t think people understood how well conditioned we were. Partly that was because when we did our practices we were constantly running, we were scrimmaging. I mean, that was practice. You’d warm up a little bit and then you’d scrimmage, so you’re constantly playing games that he would stop. And then at the end of the practice we would run this drill, which was and-two and-four and maybe and-six, so you go up and back, up and back, and then Van Breda Kolffwould say “And four,” meaning you had to go four more times, or “And two.” I remember those drills. Those were fun conditioning drills.

Van Breda Kolff was animated and passionate — team member Don Roth ’65 said he’d occasionally bang his head against the wall for emphasis during halftime talks. But he also drew great joy from the game.

Walters: He was unusual that way. He was a tough Marine, he was all those kinds of things, but you had great fun playing for the guy.

Still, learning to play in Van Breda Kolff’s system was no easy task.

Hummer: When I was a freshman, I didn’t understand it at all. It looked like just — where are the plays, where are the patterns? But they’re there, and of course, I almost marvel that we played so well, because so many of us were sophomores. So that means, we were just being introduced to the stuff that Butch did. And you have to catch on fast, and it’s subtle. It’s very, very subtle, and to catch on to it fast. I think that’s why the team improved so much during the year. You just have to keep doing it until it becomes more natural to you.

Bradley had become the exemplar of Van Breda Kolff’s brand of basketball. He was an exceptional shooter and passer who always seemed to be in the right place at the right time.

Hummer: With Bill, you’re sort of in every game. You know what I mean? You can almost play anybody, and if Bill plays well, you’re going to do well. You’re going do OK, you’re going to be in the game. And Bill rarely had an off night.

Bradley was extraordinary off the court as well. In January of his senior season, he was selected to be a Rhodes Scholar.

Walters: People can’t and don’t know the extent to which he had this aura. And in many ways almost because he never sought it. But he had an aura. You know, for those of us that were teammates he was just Bill, OK? I wouldn’t say plain old Bill, because we all admired him.

After the games, we just beat somebody or whatever, and he’s off to the library at the two o’clock in the morning. Are you kidding me? Who has that kind of discipline?

Bill Kingston ’65 was a reserve guard and one of Bradley’s roommates.

Bill Kingston: We didn’t see him in the room very much. He would come in, sometimes after midnight, and be out early in the morning to go to class and everything. Of all the roommates, he was the least present. He had a couple of favorite study spots — one somewhere in the library, and then when the library closed it, another place he went. I don’t know how much he did that during the season but he certainly did it at other times.

Bradley’s discipline was evident in his practice habits as well.

Hummer: He was such a routinized player. He had his own routine, and he would do it by himself when he took the court every day, and even before games, he would do the same routine. And Billy Kingston would rebound for him before the games and Bill would run through this same routine.

Bradley: I’d start in close and then move out and sometimes they would get there early and count how many in a row I hit.

Hummer: I can recall a moment down at the Palestra when he was doing this, and I really noticed something for the first time, something that other people had told me but I had not really noticed myself, and that is as he went through the routine, it was very clear that everybody in the gym was just watching Bill go through his routine. And this night in the Palestra, as he’s going through it, it’s one of those strange things where the ambient noise level in the crowd just starts going a little bit up, and a little bit up, and a little bit up as Bill is going through his routine, and he’s not missing anything. After a while, it’s just this roar in the crowd with every shot that goes through. It’s just very strange. It’s stuff that you don’t really see much — in real life.

Bradley boosted his legend in December of ’64 when Princeton was invited to play in the annual Holiday Festival at Madison Square Garden. Facing Michigan, the nation’s No. 1 team, the Princeton star scored 41 points and had his team up by a dozen before he fouled out with 4 minutes and 37 seconds left. But in the final minutes, the Wolverines stormed back and won the game, 80-78.

The New York Times hailed Bradley’s all-around game: “In addition to making his fabulous assortment of shots,” reporter Leonard Koppet wrote, “he defended well, picked off passes, fed teammates for four baskets, took down nine rebounds, and dominated whoever played him one‐ on‐ one.”

But Bradley remembers something different from that night:

Bradley: The thing that stands out to me is how hard everybody on the team took it and how Van Breda Kolff closed the doors to the locker room, didn’t let the press in, talked to us about what had happened, and how we have to think about things going forward. And then we got on a bus and went back to Princeton.

Fortunately for the Tigers, there would be better bus rides ahead.

Paw in print

July 2025

On the cover: Wilton Virgo ’00 and his classmates celebrate during the P-rade.

0 Responses