Owen Curtis ’72 *75 reflects on the differences between ’70s-era Princeton hippies and preps, why TV broadcasters were right to be wary of the Princeton band, and how it feels to be pranked by legendary basketball coach Pete Carril.

PAW podcasts are also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

TRANSCRIPT

Allie Wenner: If you take a look through the early 20th-century editions of the Princeton University yearbook — which is known as the Nassau Herald — it’s easy to understand why Princeton was long considered to a bastion of conformity. There are pages and pages of young white men with their hair parted in the exactly same way who identify as Presbyterian and say that they are affiliated with the Republican party. Even up through the Class of 1968, you’ll still see it: white guys in expensive-looking suits who are overwhelmingly from towns in the northeast and who have fathers who went to school here.

But by the 1970s, something changes. There are some guys who aren’t wearing ties — some of them are actually wearing turtlenecks, or sweaters, and a few of them look like they rolled out of bed just in time for their picture to be taken. But the biggest change in these ’70s yearbooks has nothing to do with attire, actually — there are black people now, and women, sprinkled in between some of the awkward mustaches and plaid leisure suits.

As an undergraduate student during the late ’60s and early ’70s and a graduate student in the mid-’70s, Owen Curtis got to witness this interesting transformation firsthand.

Owen Curtis: It was strange to go from a class of half women and half guys into just an all-male environment, even though I knew that’s what I was getting into. I didn’t realize how it perverted your view of life. So, when the women started coming the following year — I mean, when coeducation was announced halfway through freshman year we all just celebrated because we weren’t hung up on an all-male Princeton. Some of the older folks were, I think. And there were some members of the class who thought that was — what a terrible thing. So it was good.

Well I was in Wilson College, and for whatever reason, many of the women either chose or were assigned to the dorms that fed Wilson College, Wilcox Hall. So, it was the most normal place. So you got, you just got to meet them as friends. And I dated a few of the gals and was disappointed when the relationships broke off. I was stupid enough to date two roommates, for example. But, in any event, I was a young, stupid college kid.

I came into college as a pretty conservative child of moderate social but fiscally conservative Republican parents. But my brother had been here for two years and he’d already gotten liberalized a little bit, particularly about the Vietnam War. And he and his roommate leaned on me a lot about that. And I said, “I’m going to keep an open mind.” I didn’t take sides much at all. I had an American flag hanging up in my freshman dorm room.

But it was quite clear by the end of freshman year that the quagmire we were in in Vietnam was, to me was — initially I thought we were doing the right thing. We were fighting Commies. Well, turns out that it was much more complicated than that. And I learned about that at Princeton. So I did go down to the March on Washington in October of ’69, so fall of sophomore year. And it was — they said, “You need to come down with me and you’ll get — this will complete your Vietnam education.” And then his roommate said, “Yeah, plus there’ll be lots of girls.” So, I went. And there were lots of girls, and we met up with a bunch of them. It was a great weekend. It totally convinced me that Vietnam was wrong. And then you had the struggle — you knew buddies from high school who were over there fighting, so, you had to deal with that, sort of balance it out. Those guys came back and they got treated like crap compared to the veterans today. They were spit on in the street. If you were a Vietnam veteran and you came back and you walked in the street in uniform, it was not uncommon for people to harass you: “You were over there doing mean and nasty things and shooting babies.” Well, they were soldiers who got conscripted in through the draft, which you don’t have today. It was a different world.

AW: Curtis obtained his undergraduate degree in civil engineering in the spring of 1972. He got a job soon after that, and worked for a couple of years before returning to Princeton in the fall of 1974 to pursue a master’s degree in mechanical and aerospace engineering. And as Curtis tells it, he noticed a change in the student body almost immediately after setting foot back on campus.

OC: The Vietnam War was essentially done. The disaster was now known to everybody that had been the focal point of campus commentary for the four years I was here. And, frankly, a lot during high school, as well. But I had left campus where, if the weather was warm enough, you wore ragged bottom cut-offs and dirty old T-shirts — men and women. A lot of the women would go around braless. That was not uncommon at the time. They wore work shirts, blue, you know, work shirts, because you were trying to have solidarity with working Americans. And you tended to look — yeah, were there preppy guys and gals on campus? Yeah, there were. But there were an awful lot of people who were the antithesis of preppy. And there were some of us who would look in the closet and put on our preppy stuff or on our hippie stuff or something in between. But it was not a uniform Princeton Charlie, Princeton Charlene environment at all. It was very mixed and very liberal, I suppose, is the right word.

I got back two years later and I’m standing in line in McCosh Infirmary to hand in my health form and get an inoculation for whatever I was supposed to get so I could not poison the population with whatever I might have. In any event, everybody was dressed like a goddamn preppy. I mean, I wear button-down shirts all the time if I’m not wearing a polo shirt or a t-shirt. But everyone was — all the guys wore button-downs. They had their khakis. They looked like they walked out of preppy magazine or whatever it is. I was astounded.

So, it was almost all seniors in line. They were talking only about law school and getting their MBA and they were salivating over making money and it was all money, money, get rich, that’s why we came to Princeton. And I’m saying, I knew guys in my class that went on to MBA. Most of the engineers I graduated with actually went on and got MBAs. Some of them became doctors. None of them became attorneys but a bunch of other people I know went on… But we weren’t oriented as much towards career as towards having a good time for four years and getting a damn good education and then figuring out what life brought us and at the same time trying to solve the world’s problems. That’s really what I think I sensed that the class wanted to do. These people were, “Me, me, me.” And it was only two or three years later, two years later. I couldn’t figure that out. I still can’t figure it out.

Something had changed on campus. When I would occasionally walk across campus to go to the U-Store, I would look around, and it looked like a totally different place after just two years.

AW: During his undergraduate years at Princeton, Curtis was involved in a variety of activities like tennis, and he was a member of Stevenson Hall. But some of his fondest memories of his college years were formed on the field at the old Palmer Stadium and on the bleachers at the newly constructed Jadwin Gymnasium as a trumpet player in the Princeton University Band.

OC: It took about a full grade off — you know, a grade value off of my fall grades because I was so dedicated to the band. You know, long nights, all overnight bus rides up to Cornell, or to Brown, or Harvard, or whatever. It was fun. It was just a lot of fun. There was probably way too much alcohol but in general, we had fun. The shows were — you know, they tried to push it. They bordered on the obscene most of the time.

We did the 100th anniversary of the first college football game that was played at Rutgers in fall of 1969 and I was a sophomore. And it was being televised by Howard Cosell, who was the premier sports announcer of the generation and ABC Wide World of Sports. It was their featured game and a big deal about a hundred years of college football. And because Princeton had let slip a semi-off-colored joke on ABC Wide World of Sports about five years earlier they had never broadcast any more of our halftimes in the intervening five years. And they weren’t really planning on doing that during this game. So, they showed the Rutgers band and then they showed us in the background but they basically cut out the audio so you couldn’t hear the guys jibber jabbering and whatever tales they were telling for the different formations that we made on the field until we got to the last one and the announcer said, “And now we honor the nation’s foremost network of sports broadcasting excellence.” And Cosell and the people in the booth — I mean, I’m down on the field so I only hear about this afterwards. Apparently, the announcers got excited so they turned on the [band’s] announcer. And we formed a “C” and then we formed a “B” next, in front of that, and then in front of that we formed what looked like it was going to be an “A.” And then at the last minute the “A” collapsed into an “N” and what we played was bum, bum, bum, the NBC chimes. Apparently, the ABC people were livid. But they broadcast it. So, we caught ’em.

AW: In fact, several of Curtis’ most vivid memories from his Princeton days involve sports in some shape or form. Here he is, recalling one seemingly ordinary day, which started with a pickup basketball game.

OC: I went up to Dillon Gym one day to shoot hoops — play some pickup basketball. And you would typically play either 3-on-3 or 4-on-4. So I go up there, and one of the guys I know, who lived across the hall from me, was this guy Gerry Couzens. He was the reserve center on the varsity basketball team. And we were pretty good buddies, we were hallmates and whatnot. And he was playing with a bunch of the varsity guys, guys who were a class or two ahead of us, and Pete Carril, the famous basketball coach. Pete was 5-5 I think, and he had been a guard, a very exceptionally good shooting guard.

Anyhow, so Carril and all these varsity players, including my buddy Gerry, are playing basketball and I’m sitting there and, you know, you played to like 15 or 21 and then you rotated. One or two guys would come out and one of two would move in. So I rotated in and I was on Carril’s team and I was tall — maybe an inch taller than I am now. So I was playing the forward position. I wasn’t much of a shot and I never played in high school. I just played for the fun of it.

So, we played a couple of games. And then finally, we took a break. And Carril comes up to me. He says, “Hey kid, what’s your name?” “Owen Curtis.” He says, “Did you ever think about coming out for the team?”

Now, here’s the greatest college basketball coach in the country asking me if I want to go out for the team. And I’m not catching on at all. I said, “Coach, I didn’t even play in high school.” He says, “Doesn’t matter, you could walk on. We could use a guy like you.” And he paused just a bit. He says, “You make the others look good.” And then I see my buddy Gerry standing behind him with a grin on his face and I realized that Gerry had said something to Carril, and Carril had pulled that on me. I wasn’t insulted, I wasn’t upset. I thought it was the funniest damn thing that ever happened to me. And I still do. It was great.

AW: Many thanks to Owen Curtis for sharing his story. This episode was produced by Allie Wenner; and the music is licensed from FirstCom Music.

If you have a story to share, we’d love to hear from you. You can email us at paw@princeton.edu.

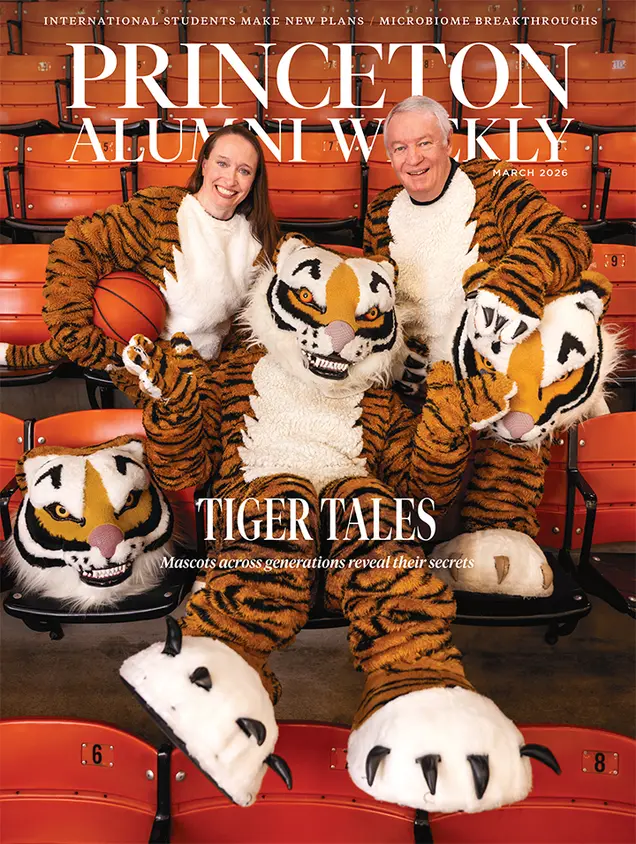

Paw in print

March 2026

Mascots across generations; biome breakthroughs; international students make new plans.

2 Responses

Dennis Grzezinski ’72

8 Years AgoOwen: I finally got around...

Owen: I finally got around to catching your interview today, and I must say that I really enjoyed it. We did have some good times with the Marching Band, didn't we? So where are you now? I'm still in Milwaukee, still doing public-interest-side environmental law, and gliding (or crashing?) toward retirement.

Keith Dix ’76

8 Years AgoBand Halftime Shows

I was a member of the Band for all four of my years (72-76) and I missed only one game, to take the GRE. Our halftime shows always stretched the limits of good taste and the patience of University administrators. Fortunately, we had a steadfast supporter in Freddy Fox. The one real peril we faced during halftimes was being run over by fans of our opponents, who would dart onto the field as we stood and played, and several times band members were badly injured.

I met several of my best friends in and through the Band and am still in touch with them.