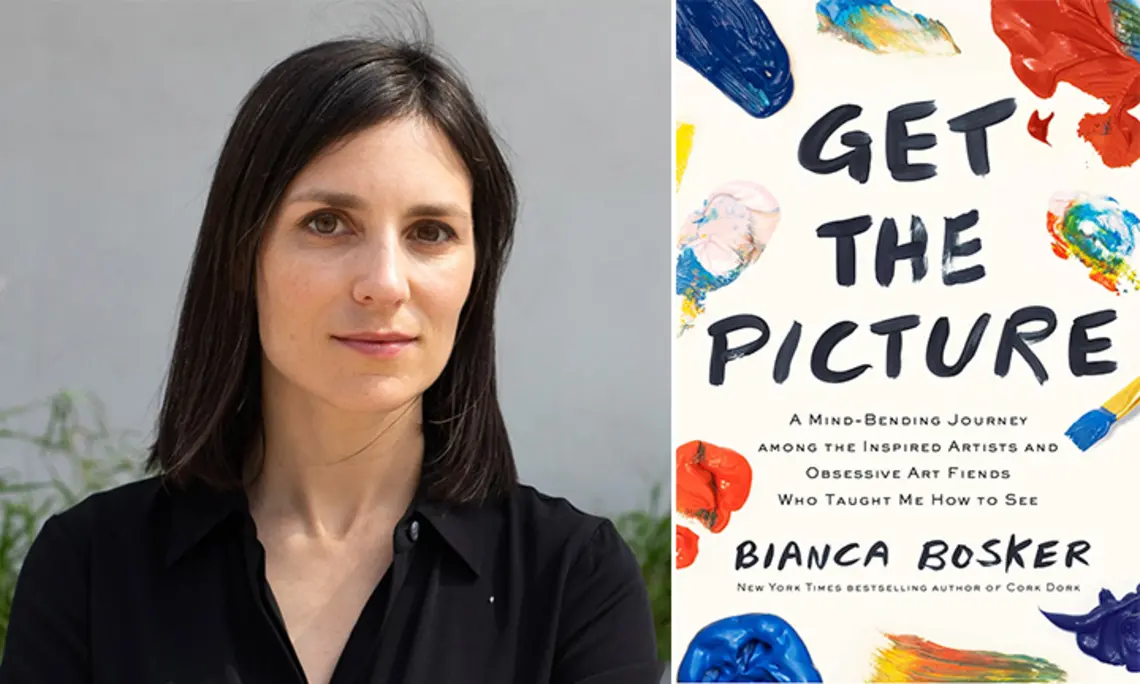

Bianca Bosker ’08 on Cracking Open the Art World

‘How does an artwork go from being the germ of an idea in someone’s studio to this masterpiece that we obsess over in museums?’

On this episode of the PAW Book Club Podcast — where Princeton alumni read a book together — Bianca Bosker ’08 talks about her latest book, Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See, for which she ventured into the secretive and exclusive world of fine art. She was trying to answer what you’d think would be an easy two-part question: What counts as art, and who gets to decide? But as she talked her way into galleries, art shows, and museums, getting to know artists, collectors, and curators, the answer turned out to be anything but simple.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT:

I’m Liz Daugherty, and this is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s PAW Book Club Podcast, where Princeton alumni read a book together.

Today, I’m speaking with Bianca Bosker from the great Class of 2008 about her latest book titled, Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See.

This is the second deep dive Bosker has taken. For the first, she wrote about the wine industry for a book called Cork Dork. This time, she ventured into the secretive and exclusive world of fine art. She was trying to answer what you’d think would be an easy two-part question: What counts as art, and who gets to decide? But as she talked her way into galleries, art shows, and museums, getting to know artists, collectors, and curators, the answer turned out to be anything but simple.

So Bianca, thank you so much for taking the time to come here today.

Bianca Bosker ’08: My pleasure. Thank you so much for having me. I actually saw a fox on the Princeton campus for the first time on my walk up from the Dinky, so it’s been a really exciting day so far.

LD: That’s a real Princeton experience right there.

So we loved reading your book at PAW, and it generated so many conversations in the office, and we have some great questions here. I’m going to start with one by Jeff McCollum from the Class of 1966, and he wrote, “I was fascinated by your personal journey to self-discovery and would love to hear more about that.”

And he’s right, you framed this book as your own journey, so did the experience of doing this change you at all?

BB: In so many ways. These projects, both Cork Dork and Get the Picture, have been all-encompassing. This new book took me about five years and it totally upended my life in the process. I mean, I gave myself over to the art world. I am a journalist who believes in learning by doing, and so I really wanted to throw myself into the middle of the action.

I wanted to understand, first of all, how does an artwork go from being the germ of an idea in someone’s studio to this masterpiece that we obsess over in museums? Because I felt like all the decisions that shape that artwork also shape us — our idea of art, who makes it, why we should engage with it. And I also knew from past experience that it’s very different to have a polite, sanitized interview with someone than it is to spend hours on your feet selling wine at a restaurant or hours at an art fair, schmoozing with millionaires trying to get them to splurge on photographs or paintings. And I also, just as an individual, believe that the miraculous often emerges from the mundane, and so I wanted to just see how people would put one foot in front of the other, what kept them up at night, how they would pay their bills.

And so for me, this was a journey that, to Jeff’s point, changed how I thought about art, but also changed how I experienced the world as a person, full stop. I mean, I experienced identity crises when it came to the matters of my own taste. I began to look at the very mundane experience of walking down the street the way that I think artists look at it, which is this ability to linger with the everyday and examine it the way that they look at art with this extra beat, with this willingness to appreciate the sort of fragile miracle that is the everyday world around us.

This is something I threw myself into as a writer, but just as a person. I mean, I spent, as I write in the book, hours and hours with people in their studios, in the galleries. I was spackling walls until 11 at night. I was sanding sculptures until one in the morning. I did not see a lot of my loved ones for quite a while, and they were very understanding about that I think. I hope.

LD: You know, I have to ask, do you create art now? Has this turned you into an artist yourself?

BB: So I came to Princeton, and actually, I took a couple of art classes, so I think of it’s like adult Bianca grabbed the wheel, and I never studied art history, did take classes in econ. And I wasn’t really engaging with it. When I graduated, I told myself, OK, if I wasn’t going to be an artist, at least I would engage with art on a regular basis.

And that plan lasted basically until I tried to start seeing art on a regular basis and I just felt so out of my league. I felt like I didn’t know the language, I didn’t know how to carry myself, I didn’t know how to dress, I didn’t know the isms, the periods, I just felt like I didn’t belong and I didn’t know what was going on. And admittedly, I took the coward’s way out and withdrew.

And it wasn’t until a few years ago that I reconnected with art, and that actually grew out of this experience of cleaning my mom’s basement and finding these old paintings by my grandmother inspired by her time as a Holocaust survivor in a displaced person’s camp, which I guess I’m trying to say that book ideas, you should really help your mom clean the basement. That’s where it all begins.

The thing that I am doing, and I don’t know if you can call it capital-A Art, but as a parent to young child, I feel like I’m engaging in arts and crafts in an everyday way that is so exciting. So over breakfast most days, I’m drawing excavators and cement mixers. And you might think that doesn’t count as art, but I was touring a show the other day and I was like — I saw this actually incredible Basquiat sketch of an excavator, so why not?

LD: So Jeff McCollum, again, Class of ’66, he also asked, and this again, it really gets into a part of your book, “Of all your stories, your relationship with artist Julie Curtiss resonated most strongly with me. Can you say more about that relationship and especially the parallels she drew between her work and Jungian archetypes?”

BB: Julie Curtiss was in many ways my art fairy godmother, and I think that the relationship between a journalist and the person that they’re writing about is a very unique one. And I encourage anyone who hasn’t read it to read Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer, which investigates this subject in a really interesting way. The first sentence alone is incredibly strong and damning. It’s something like, “Any journalist who is not too naive or too stupid knows that what he does is morally indefensible,” so it’s a strong start.

But that experience, the kind of reporting that I did for this book was incredibly intimate. People welcomed me into very private spaces, spaces where they were engaging in the incredibly high-stakes work of creating. And I, well, first of all, was incredibly grateful to Julie for that, all the more so because I just sensed there was something special about her work. It stuck with me, it kind of haunted me. And I think there’s some artworks that I see that sort of flit from your brain as quickly as names at a cocktail party, and then there’s some that take up residence. They declare squatters’ rights. They will not leave you alone. And her work was like that.

And so I wanted to get back to this person who’d made something that wouldn’t quit me, and I also just sensed that she engaged with the world in a very particular way. So many artists that I met intrigued me because they basically acted like they’d access these trap doors in their brains. Their reality did not operate according to rules of nature that I found remotely familiar, which was so exciting, and it made my life feel so claustrophobic by comparison. And Julie not only had a fascinating perspective to share, but she also had the guts to share it.

And one thing that I hadn’t expected when I first began poking around the art world was just how secretive and closed off it was. I mean, I am someone who’s written about a huge range of topics, super tall skyscrapers, feuding geologists, including Gerta Keller, who’s part of the geology department here, witches, supermarkets, you name it, and I have never encountered an industry that was so difficult to get access to. And so when I started asking what I thought were pretty innocent questions, like how do you do art. I was surprised to get threats and warnings, people who told me that what I wanted to do was impossible, vaguely even dangerous, that it was a terrible idea to try and get into this world as a journalist if I wanted to keep living in New York City.

And Julie was brave. I mean, Julie was willing to take a risk in letting a journalist into this sanctum sanctorum of her studio for hours on end with a recorder, with a notebook. And the longer I spent in her studio, the more clear it was what a radical act that was. I mean, there came a point in her career, and she was someone who had just tipped over from being a super emerging artist to beginning to sustain herself off of art sales, which is not a given at all in the art world and is not the experience that most artists have, and yet, even in this still very fragile, early point of her career, she was subject to a lot of bullying and a lot of anonymous naysaying that took me by surprise.

It was very unpleasant to witness, and it was a very strange experience to be there, knowing that I would one day probably write about something that other people might critique the way that people were anonymously and very, I think, unfairly critiquing things she had said in interviews in the past.

LD: You mentioned the secrecy, and let me jump in and ask something that I was wondering about as I read the book, which is the secrecy and the exclusivity of the world took me by surprise too because again, as a journalist, if you’re proud of what you do, you talk about it. And that was not what you found.

So I’m curious. My dark assumption is that that secrecy is built to protect something in order to make it more clubby, make it more exclusive, make it more expensive. But is there more to it, why people want to keep what they do so quiet? You know what I mean? Tell me that my dark impulses here are wrong and there’s a better explanation than that.

BB: Right. So I think that there is what I would describe as a strategic snobbery that the art world uses to keep people out. And I think for me, it was both disheartening but also empowering to see how that worked. Right?

And so I started working at galleries and I began to be initiated into the different ways that these gatekeepers deliberately erect barriers to entry. So the language, for example. Artspeak is, I mean, these days to sound like you know something about art, the trick is basically to sound like a French professor who’s been the victim of a terrible translation job. I write about some of the examples in the book, but it’s not “a website,” it’s “an online viewing room.” A piece is not “sold,” it’s “placed.” “Indexical marks of the artist’s body” would be artspeak for “finger painting.” And that’s just one example of this agreed-upon code that exists not for clear communication, but to delineate who’s in and who’s out.

And artspeak unfortunately crops up everywhere. It’s in gallery press releases, it’s in the wall text in museums next to paintings. And ostensibly it’s there to elucidate, but to me, it mostly serves as the world’s hardest reading comprehension exam.

Where you locate galleries, a lot of galleries are located less like stores than speakeasies. They can be very hard to find. They don’t share prices and then they refuse to sell you things even if they’re for sale.

There’s also ... How would I put this? There’s a lot of judging that goes on. I mean, my boss pulled me aside to tell me that I wasn’t the coolest cat in the art world, so having me around was just lowering his coolness. So it was suggested that I may adopt a dress code, a strict haircut, no jewelry, may think about toning down some of my “superficial enthusiasm.”

And so I think that that’s just the tip of the iceberg and just some examples of the way that if you, like me, have had these encounters with the art world and they’ve left you feeling a bit alienated, you are not nuts. These are deliberate, and not everyone does that. I mean, there are so many people in this world who do belong to this rebel alliance of individuals who believe art is for everyone, that more people need to love it, they just want to see more people embrace it.

At the same time though, there is a significant and very influential cohort that views secrecy as key to their survival in the art world. And part of it is that there are things that go on that, to an outside observer, could pass as absurd, unethical, illegal in some cases. And so for those of us who haven’t sworn this mafia-like omerta vow of silence, you’re seen as a bit of a risk. So that’s part of the vetting process. It’s like, “OK, are you one of us? If so, you can begin to get in.”

But I also think, to your point, it exists to build mystique. It concentrates power in the hands of gatekeepers. It also unfortunately creates this aura where art is seen as something that’s for a select few, a select, self-anointed few. I was really taken aback by the fact that one of the gallerists that I worked for, who was someone who believed in art’s power to change the world, actually seemed wary of doing things that would let more people in.

And that was just one example of the many tensions and hypocrisies that exist in the art world, this idea that, OK ... To me, I was like, “OK, if you want this to change the world, you’ve got to let people see it.” And we would have discussions over whether a journalist shedding light on this world was even a good thing. And of course, I think it does. I think information is power, but that sentiment isn’t maybe as popular in the art world.

LD: Well, you’re a journalist.

BB: I’m biased, yes.

LD: There you go. There you go.

So that actually brings me nicely to a question that we’ve been wondering a lot around the PAW office. This was the number one thing that came up was what did Jack think of the book? And what we really meant by this was, are you still in touch with the people you met and wrote about, especially Jack, he was so interesting, the gallery owner and the first person who kind of let you into this world. Because he seemed so worried about what you were going to write. So how did it go when all these people saw you rip off the cover of the art world and expose it?

BB: Yeah, so Jack ran, at the time, a very cool up-and-coming gallery in Brooklyn, and he was one of the first people to let me in. And for that, I remain so grateful. I mean, he opened my eyes to so much. He took me by the hand. He was willing to have the difficult conversations, and also illuminated really important through-currents in the art world.

Since the book has come out, I have shared copies of it with all of the main people that I ended up writing about in the book and I haven’t heard from everybody, though the people that I have heard from have been incredibly positive and supportive. I mean, Rob Dimin, who’s one of the gallerists that I ended up working with as well, he hosted the book party for the book. As part of that, I organized a mini art show of work by some of the artists featured in the book, and they were kind enough to lend works to the show, people like Julie Curtiss and Clinton King and Liz Ainslie, Mitchell Algus. There’s a collector couple called the Icy Gays who I embedded with, and we’ve stayed in touch. They’ve shared the book widely.

And to Jeff’s question about my relationship with Julie, as I was saying before, it is very intimate and you spend long, long, long hours with people. And I care about them, not only as a writer, but as a person.

One of the most gratifying things that has happened since Get the Picture came out is hearing from artists who’ve read the book. I’ve gotten emails, DMs, people coming up to me on the street telling me that the book really resonated with them, that they as artists recognized a truth in it, and that a few of them have told me, “I want everyone in my life to read this so they understand who I am and the world that I’m in.” And I do think that artists are the ultimate conscience of the art world. None of us would be here without them. They know where the bodies are buried. And so for them to say that there was truth in this and that they recognized their world, their values, the reason that we need to make art a part of our lives in reading it means so much to me.

But yeah, but not to say that it’s uncontroversial. I was on a panel recently and an art critic launched into a rather surprising and certainly unprompted critique of what he saw as the flaws in the book, which of course I have a rebuttal for, but it was interesting to see that he needed to get that off his chest.

LD: Ah, that’s interesting. Well, you got a reaction.

BB: I got a reaction. And I do think that ultimately, truth is nuanced and the world is nuanced. And so I think that while I do ultimately think of this book as a love story, I also think that like with any love story, there’s the agony and there’s the ecstasy.

LD: So David Marcus, Class of 1992, asked, “What similarities did you see between the worlds of art and wine?”

BB: It’s a great question, and I was expecting to find a lot more similarities.

So for those who haven’t read Cork Dork, what are you waiting for? No, I’m just kidding. No, but that book was basically about how I quit my then-job as a tech editor at HuffPost to train as a sommelier. And so it was all about the world of wine, but also to me about these forgotten and neglected senses of taste and smell and the values of living life more sensefully.

And I think that for me, going into it, I thought, “OK, well ...” You think it’s a similar demographic, right? Art, if you go to an auction, you think about auction houses, which for many of us is the public experience that we read about in the paper of art and wine. It’s like, OK, these are rich, predominantly white individuals buying things, and they seem like they’re ... How do I put this?

LD: Do you want me to say it for you? Both on the outside, it seemed to be very snobby worlds, just from the outside. A certain PAW editor called them “insufferable.”

BB: Insufferable!

LD: Totally that’s an opinion. But you lived through it.

BB: Well, I think that as someone who also was not of these worlds initially, I also found them insufferable to a point. That’s what kept me away for a very long period of time. And what ultimately convinced me to get into these worlds was ultimately the passion of the people in them. I am someone who is obsessed with obsession, and so I find that passion really magnetic.

And in particular, it was this passion that people felt for something that I did not appreciate. And it was so intense that it was a sort of obsession that made me think that everything I thought about how to live a productive, rich life as a human being was wrong. And so it convinced me in both cases to move past the superficial insufferableness of it and go deeper.

And I guess rather than the similarities, what jumps out to me right away are what I see as one very big difference, which is context. So when you’re training as a sommelier, you do a lot of blind tasting of wines, which basically means you have a glass of wine in front of you, and you have to figure out what it is based solely on the liquid in the glass. So what grapes was it made with? Where did it come from? When was it made? Blind tasting really forces you to ignore all the things that are designed to play to your sensory biases. You just have to stay true to your own felt experience of what is in the glass.

Now, when I started getting into the art world, I was really surprised by just how much so many art experts seemed to spend, to me, rather little time discussing the merits of the art itself. And instead they ask questions about it, like where did the artist go to school? What gallery showed the work? Who is this artist sleeping with? Who are their friends? All of that was, in the art world, referred to as “the context.” The web of names around an artist, the social cachet of that individual, and that seemed to influence individuals’ judgment of the works so much more than the pieces themselves.

As one dealer put it, “If you don’t understand the context, you can’t understand what the F you’re looking at.” And this was an individual whose question, when deciding whether to show an artist, was often, “Is this someone I would want to hang out with?” So that ancillary part of that artist’s identity played a big role for many connoisseurs in judging what was the value in the art world.

I had this culture shock of going from wine to art where art, it felt like, no, no, no. I was being told that the experience that you have in front of the work somehow is not as important in judging the work as all this other ancillary information.

And I do think that, look, context influences us all the time. I’m not naive. What surprised me about the art world was what I saw as a sort of unapologetic emphasis on it. Rather than saying, “OK, I recognize I could be biased about the fact that this person has an MFA from an Ivy League school,” it was like, “no, no, this is front and center information that you have to have in order to fully understand what you’re looking at.”

And it wasn’t until later that I began working in artists’ studios, I felt like I began to suss out a different way of engaging with the work, one that simply involved staying in the art, just paying attention to the decisions that an artist makes, and paying attention to the physical form, which is not something that we’re often taught to do in an age where, for the last hundred years, we’ve been told that what matters about an artwork is really the idea behind it rather than the physical thing.

LD: That’s actually kind of the opposite. That’s so interesting that you look at the wine with no other information versus it’s the information that turns a stack of appliances from a stack of appliances into a work of art.

BB: Right, right.

LD: It’s all that context. Without it, it’s-

BB: A stack of appliances.

LD: ... curbside.

BB: Right, right.

LD: Yeah, exactly.

BB: Right. And I do think that artists have this ability to cast away the context. Ultimately, this is not where I start at the beginning of the book, but ultimately I came to agree with the perspective embraced by many scientists and certainly by artists that art is a fundamental part of the human experience. It is necessary to us. It is not a luxury. It is not something that we simply invented after we learned to live past age 20 and got tired of staring at blank cave walls, but something that has been crucial to our survival.

And there are a few explanations for that, but one that really resonated with me is this idea that art helps us fight the reducing tendencies of our minds. Art, like dreams, introduces these perplexing, unsolvable images, and they are a glitch. It is a glitch that’s also a gift, and it’s one that helps our minds jump the curb and lift off these filters of expectation that are constantly shaping our experience of the world without us necessarily realizing it.

LD: So David Marcus also asked, and I think this was interesting: “You talk a lot about the art market. How do you think Instagram and similar apps change the market and perhaps threaten the current gallery system?”

BB: It’s changing things, for sure. I think that there’s certainly a way in which artists can build a platform. They can show their work to people without needing a gatekeeper. So I think it’s been a very valuable tool for discovery for many. Many collectors find artists on Instagram. I mean, I was so interested in the way that really dedicated collectors are ultimately really private investigators, and they’ll begin to sleuth out artists that they want to buy by looking at, “OK, this artist is liking posts by this other artist,” or “this artist I see is hanging out and friends with this artist. Now if I like this person’s work, maybe I should check out this person’s work,” or, “oh, this curator is following this artist. I should pay attention to them.” So there’s all these, I mean, that’s more context for you that you can suss out on Instagram.

So I think that certainly it does provide a way for artists to show their work, if not in person, which is, I think, most artists’ ultimate goal is for you to be there as a body with their work in space. Nonetheless, it does give artists a way to show their work to the world, to sell it directly to people if they want.

On the other hand, traditionally there has been this idea that galleries offer a sort of imprimatur, right? There’s a sense that if you want to access the annals of art history, you need the support of the stamp of approval from a gallery, and also just the public recognition and public platform that that provides.

But I think it’s very exciting to see. I think anything that gives artists more power over their careers and anything that makes it easier for more of us to engage with art and support artists is a really positive development.

LD: So similarly, when we’re talking about social media, I had a question from PAW’s managing editor, Brett Tomlinson. He said, “With the AllFIRE experience in mind,” and really, you should read the book if you haven’t, just for that chapter is amazing, “where’s the line between social media influencing and art?” Because AllFIRE was kind of both. She was doing social media influencing, but what she was producing was art, and is that line blurring or maybe solidifying as artists and non-artists get deeper into social media and use it in different ways?

BB: Well, this is right at the crux of what Mandy AllFIRE was exploring with this project. Am I allowed to say “ass”? Are Princeton alums allowed to say “ass” on a podcast?

LD: Yes. The odds that small children will listen to this are very slim, so go for it. Yeah, we’re good.

BB: Well, in this context, it is an artspeak term because we are talking about ass influencers. No, I’m just kidding. It’s not artspeak.

But basically, so Mandy AllFIRE, for those who are not familiar with her, she is an artist who I encountered via another artist who, to get the context, MFA from Columbia, track record of performing at some very, very well-respected art venues. When I met her, she was performing as an ass influencer on Instagram. And for those august alumni who are not familiar with this term, this is basically someone who has acquired a very large social media following because they’ve posted pictures of their butt. And for this particular solo show, she had invited her many hundred thousands of fans to come to a gallery for a live face-sitting where she was going to sit on their faces until they couldn’t take it anymore. She ended up sitting on my face for seven minutes. Again, the places your Princeton degree will take you.

And her work wouldn’t quit me. I mean, I was just fascinated for many different reasons with what she was doing. And one of them was it did raise this question of what is art? And I realized that was a very fundamental question that I couldn’t answer. And I think that ultimately, well, this is not an easy question to answer in a sound bite. As it turns out, the experts have basically thrown up their hands on answering it. They’re like, “We just don’t know in this day and age.”

But what I was very fascinated to learn in the process of trying to answer it was the fact that our general idea of what art is today is inextricably linked with these rather arbitrary decisions that were made in the 1760s by rather status-conscious, sort of snobby Europeans where they decided there were some limited human activities that counted as art, like painting, sculpture, poetry, and that basically everything else was mere craft, and art could move your soul, craft was useful, but that was about it. And yet, for thousands of years, art had been considered anything involving human ingenuity and skill. So training horses, passing laws, carving marble.

And so I think for me, that was my first clue that art could be something more expansive than I had originally anticipated. And that hunch was confirmed when I began to dig into actually the science of art. And scientists who have researched art throughout humankind’s existence argue that it is a universal impulse. And there’s a fascinating area of scholarship where it argues that art is basically anything that involves making special, taking something and codifying it or repeating it or just calling to attention to it in a specific way.

And so Mandy AllFIRE actually does belong to a pretty robust body of research that suggests that perhaps an Instagram influencer, a Kim Kardashian is a sort of artist perhaps. Now, it’s not for everyone. I realize that may sound like that a controversial contention, but nonetheless, to me, it got me to a place where I began to think of art as a decision on the part of the creator and the viewer. I think there’s almost a handshake that happens. Someone puts something out into the world, and it’s up to you as a viewer to either pick it up as artwork or not, to engage with it as an artwork or not.

LD: So if you could change something about the art world after all of this, if you could reach in and change something about how the whole thing operates, what would it be?

BB: Ooh. Just one thing?

LD: Or a few. You can do a few.

BB: Well, look, I do think that I would love to see it be more welcoming and more open. I do believe after this experience that art is fundamental to our experience as human beings, and I think we should act like it. I think we should dismiss the made-up language. I think we should try and root out the pretension. I don’t think that art needs all of these velvet ropes in order to be magical.

That being said, I also think that there’s work that any of us could do as viewers. At the outset, one of the things that drew me into this was that I wanted to develop my eye, and an eye to art connoisseurs is this painstakingly cultivated outlook that enables you to see a lot that doesn’t meet the eye, like who’s going to be the next Warhol, or what is transcendent about a sculpture of decaying produce on a stained mattress? And a lot of artists told me that I lacked visual literacy, which is not having an eye, which they said was a really dangerous thing in a world like ours where we are so saturated with images. And you think about it, we have Instagram, billboards, just advertising, everything’s trying to influence us. These images around us are not neutral.

I think that developing our eye is a way that we, as buyers of art, as viewers of art, can begin to move away from context. And in the process, I’m hopeful, support a greater diversity of forms of artmaking, of expression. I think that there is this myth in the art world of artificial scarcity. There’s an idea that genius is in short supply. That’s a myth that serves the market very well. It’s also, I believe, a myth. I think that there is so much great art out there. And I think the emphasis on context can lead to this winner-take-all model where a small number of people reap an outsized share of the rewards.

I also think that there’s a value to seeking out unexpected art, art that we think we might not like, art that we don’t know. As much as I love museums, I also believe that there’s a lot we can gain by spending less time with the “masterpieces” and more time in art schools, at the galleries and basements, in the art shows someone hosts in their living room. I think all of that would be better for the art ecosystem and ultimately for us as individuals.

LD: So this is my last question. Peter Barzilai, who’s our PAW editor, he asked, “What world do you want to dive into next?”

BB: Oh, I don’t know! I don’t know. I would love suggestions, welcome anybody and everybody to reach out. I always love story ideas, whether it’s for the articles I’m working on or for books, or also just because I love hearing about what people do with their time. If you ever sit next to me at a dinner party, you will know it’s like getting drawn into some backroom by a customs officer. I have a lot of questions.

So it’s just bianca.bosker@me.com. Send me a note. I actually had one reader reach out to tell me that I should become a radiologist, so that was a very next, important field. People have suggested I write about everything from, I don’t know, the world of horse racing to real estate.

These projects for me emerge both out of a curiosity, but also out of something deeper, something that’s perhaps even more spiritual. I feel like I come across something that has a seismic effect. I feel like there’s some earthquake that’s gone on in my life and I can’t help but go as deep as I can to figure out something that keeps me awake at night, both as a journalist but also just as a human being.

LD: Well, we’ll make you a shortlist at PAW. How does that sound?

BB: Yeah, thank you. I appreciate it. Absolutely.

LD: We have plenty of ideas. Well, you know what? Thank you so much for taking the time to do this today. We really enjoyed the book. This has been fantastic. Thank you so much.

BB: Thank you. I’m so grateful to you for reading it, and so grateful for being here with you today. So thank you.

The PAW Book Club podcast is produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly, and anyone can sign up through our website, paw.princeton.edu. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode, also at paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

March 2026

Mascots across generations; biome breakthroughs; international students make new plans.

No responses yet