A Conversation at Princeton’s LGBTQ+ Affinity Conference

Recent graduate Reina Coulibaly ’24 sat down with writer Ara Tucker ’01 to talk about career paths and the Every Voice event

On this episode of the PAWcast, we bring you a conversation. Reina Coulibaly ’24 and Ara Tucker ’01 connected recently at Princeton’s Every Voice affinity conference celebrating LGBTQ+ alumni. Coulibaly asked Tucker about her career path, her recent book publication, and her experience at Princeton as a fellow alum who identifies as a queer Black woman.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

I’m Liz Daugherty, and this is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s PAWcast, where we talk with Princetonians about what’s happening on campus and beyond.

In this episode, we bring you a conversation between Reina Coulibaly, who just graduated with Princeton’s Class of 2024, and Ara Tucker, from the Class of ’01, who just published her second book, titled How to Date a Black Girl. Both identify as queer Black women, and they connected in September at Princeton’s Every Voice summit celebrating LGBTQ+ alumni, where Ara spoke on a panel about intersectional identity.

With Coulibaly, Tucker discussed her career path, which took her into law school, Princeton’s administration, and later into diversity and inclusion work back before DEI was a buzzword. She also talked about how being a part of the Princeton community has fundamentally influenced the way she relates to the multitude of identities she carries.

RC: Could you tell me about your experience at Princeton as a person who holds the identities that you do?

AT: So a few defining moments of my Princeton experience. One was actually before I set foot on campus as a matriculated student. I was an admitted student, looking at various schools. And I went to an admitted students program, and Professor Howard Taylor, who was a sociology professor, he said something very profound, in which actually, made me actually change my early action decision, and actually decide to come to Princeton. But he said, “We don’t presume that because you’re a minority, you need help. But we want to make sure that if you are a minority and need help, that it’s there.”

And for me that was a great signal, a great affirmation that when I got to Princeton, I could choose how I wanted to be, and what I wanted to be. I was going to be a second generation Ivy League student, so my mom and my stepmom both went to another Ivy, we won’t name it here. So for me, the issues weren’t necessarily around first-time access, but I still was very acutely aware that I wasn’t going to look like a majority of the folks around me. And I might not even have the same background, growing up in a predominantly white neighborhood in northern New Jersey. And so I just was very interested in a place that was going to let me start to figure that out.

You know, when you’re in high school, you’re not that informed about the world. You feel like you know a lot. I felt like I knew a lot. And I was grappling with coming to grips with being a lesbian. I had, I think, worked through what it meant to be Black, but that was still in progress. But adding on top of that, something that I didn’t share with my family of origin, it was complicated.

And for me, at first, I thought college would be a safe place to not grapple with that. I actually wrongly assumed that Princeton would be a place that was not welcoming to that part of my identity. And on some level, I think it’s Foucault, but it could be some other one who said, basically, “When you repress things, they have nowhere to go but out,” essentially. And my very first interaction with being a freshman on campus, I remember was Reflections and Diversity, which was an orientation program. And everybody filed into Richardson Auditorium, and we’re all sitting there, and there’s a panel of students who felt like the oldest wisest people in the world to me as a new freshman.

And I remember one of the panelists, she said, “There are some things you may notice about me. I have red hair, I’m a woman, blah, blah, blah.” And she said, “There are some things you may not. One of which,” and again I’m paraphrasing, because sands of time, but, “that I’m a lesbian.” And I was like, oh, my God. I was like, she’s saying this out loud. I was waiting for somebody to come and yank her off the stage. I was looking around, to say, did anybody notice what she said?

And from then on, it was almost like I couldn’t stop finding people who were actively identified with this part of my identity that I thought I would be so comfortable and safe keeping in. And so I guess to your question, of why did that statement from an admitted students day resonate, it was because it just kept becoming a truism of, at Princeton, I felt like it was a place of academic inquiry and discovery, but it was also a place of personal discovery.

I met my first girlfriend here, I came out here. Many of the professors who were formative for me, so Edmund White was my first creative writing teacher. Sue Friedrich, who’s a very well-known filmmaker, was one of my first film teachers. And on and on, Margaret Vendries was one of my thesis advisors. And she was the first Black African-American Ph.D. in art history. And she was also an out lesbian, and super proud and super fierce.

And so for me, this ability to see people who were both working in fields that I was interested, but also living lives out loud, and exposing me not only to their academic rigor and their professional accomplishments, but showing me what it looked like to live as a lesbian, and giving me some role models that I might not have been able to find otherwise.

So I think that that’s stuck with me, in terms of how I now think about my role as an alum. I am in my professional life, I am the head of HR. I think about, how do you create workplaces where people feel like they belong? And as a creative writer, I also try to represent some of these experiences so that people don’t feel like they’re alone or the only one. Because for me, that was one of the most important things, to know that even if you are a first or an only, if you look closely enough, there are probably lots of others who are around who can be supportive.

RC: So can you tell me a little bit about the social scene? What was it like making friends, finding other queer people, finding other Black folks? What was it like in the banalities of day-to-day life? What was that like?

AT: So one of the things that actually I think about, how do people even become who they are? A lot of it’s serendipity. So for instance, I was the sales director for WPRB, and one of the reasons that happened was I thought I wanted a radio show. I was like, “Yeah, I want to be a DJ.” And I walked in and they were like, “If you like top 40 ...” And I was ... “... maybe not the place for you.” And I was like, oh.

But then the sales director, she stood up and she said, “If you like to be in control of your own destiny, earn money ...” And I said, “I like that.” And I ended up doing that. And through her, actually, she was an Ivy, but she was also doing something interesting, which was, she was going to go to medical school, but she was an art history major.

And for me, that was the unlock. That was the, go do the thing you’re really interested in, and if you can go to medical school and be an artist history major, the world is my oyster. So I think that was one of the ways I was occupied outside of class.

In terms of what was my social life, and the other, a lot of my friends, I joke, because I met a lot of people just through my residential college. So I was in Wilson. I think it’s renamed, it’s Hobson, right? Which is exciting.

RC: No, it’s First.

AT: It’s First.

RC: First.

AT: Sorry, it’s First. Thank you. I was in Wilson. And my RA group was pretty close. I did Outdoor Action. But I did mention, because we’re at the Every Voice Conference, my first girlfriend I met at Princeton. So she was two years behind me, and she was in diSiac, the dance group.

And then my little sister, who is seven years younger, class of ‘08, she was in diSiac. Even though I’m not a dancer, I joke with them that I was very important to diSiac. So that’s how I met a lot of other students. In terms of Black folks, I don’t think I had that many Black friends or joined a lot of Black-affiliated groups. One of the reasons was, and I think I mentioned this earlier, I was pretty conflicted about my Black identity at that time. I mentioned growing up in a predominantly white neighborhood. I went to private school until high school.

And my parents had very different upbringings. They grew up in Newark, New Jersey, so predominantly Black neighborhoods. My dad actually did grow up in the Italian section of Newark, so I can’t say that. But they were both very comfortable. They had Black friends. Obviously, I had family friends. And they put me in Jack and Jill, which is an organization for African American families.

But I always just kind of felt, I guess growing up in the late-’90s, felt a little bit like I wanted to choose my friends because of who they were, not what they looked like. And on an academic level, I understood the importance of understanding what my racial identity meant, in terms of community, but I didn’t necessarily feel it organically. And so my junior independent work was, I think a little bit of a temper tantrum, but it was called “Black Like Us.”

And I did interviews of African Americans, representing different generations, starting with my grandmother, going on to my youngest sister who’s 10 years younger, and all in between, different people just talking about what it meant to be Black to them. And realizing that class was also something that was overlaid, in my experience, that was different from my parents’ experience. And it was going to be different for folks who came after me.

So I think at Princeton I was working through what that meant. And I remember screening it in a class and having classmates say, “Wow, I didn’t know Black people lived like that. You were a debutante? Whoa.” So that was one element of it. But I never felt hostility. I guess that was the other point, was I felt, even though I didn’t have a lot of Black friends, I didn’t feel like I couldn’t, if I didn’t want to.

I think similarly with the LGBT folks, I think that was just a little bit harder. I think it was kind of this game of, is that person gay? Is that person? And I think a lot of my friends actually came out later than I did. And so on some level, I feel like hopefully I made it easier for them, or at least a little less scary. And that was my senior thesis, actually, the public and private spaces of coming out.

RC: So, pivoting to your career.

AT: Yes.

RC: This project, “Black Like Us.” I’ve seen your website, “I’m Here Too,” your novel work, your short stories, all this stuff. One through line that, from what I’ve seen, is this intersectionality of bringing in different facets of yourself and making sure that your work includes representation. So what you were saying about generational stuff, “Black Like Us.”

And so can you tell me a little bit about how your life at Princeton might have inspired you to pursue all of these different things? Tell me about how you built your career coming out of Princeton.

AT: Right. I know, it’s a little interesting.

RC: It’s awesome.

AT: Thank you. I think on some level, it all comes back to childhood. I went to a Montessori nursery school, and a lot of the Montessori philosophy is around self-directed but guided learning. And so you could be in circle with your friends, but then if you want to wash dishes, go wash dishes. If you want to polish silver, and interesting chores. But you want to read, read.

And I think I approached my Princeton education that way. I mentioned that I ended up as an art history and visual arts major, but it took a little while. I think that after I decided not to be an English major, it was kind of like, I could be anything, within reason. And I remember taking a freshman seminar with Tom Levine, and it was the question of the essay film, it was cinema and philosophy. And I went down this really deep rabbit hole of film theory, and I was all excited about pop culture, and theory, and all these things.

You learn new languages here and you get excited. And I remember thinking ... And he was very encouraging. I was like, “Oh, you should make your own major.” So you read, and it’s like this very little thing about what you have to do to make your own major. So I went door to door to different departments, like, “Will you be my major? Will you be my major?” And I remember saying I wanted to study women, but not just women’s studies. And I remember a professor saying, “Why would you want to study women?” And I was like, “What? I don’t even ... . What?”

So finding that there was actually a program within the art history department that would allow me, mainly through focusing on studio art, pursue all of the different links that I wanted, finding an institutional home was important. This leads to your, how did you navigate?

I think I truly believed, when I graduated, that when I went to NYU Law, I told myself this story, that I was going to be an entertainment lawyer, that I was going to help other artists, and that I would still somehow find time to be my own artist. What I knew about myself was I did not want to be a working artist. I find it very ironic that I’m now married to one, and I actually have affirmed that she’s the right person to do that kind of work, and I am not. It’s a daily, daily grind.

So I went to NYU. I quickly realized that, after taking some intellectual property classes, that entertainment law was probably not my interest. But I did get very excited about corporate governance. At the time, Sarbanes-Oxley was a hot topic, and Enron, and WorldCom. Now maybe people don’t know, but basically, companies that imploded and really took a lot of everyday people with them, in terms of loss of stock value and company value.

And a lot of the discussion was, what went wrong with those boards? Where was the oversight? Who was watching? And this notion of, what was the board composition and what would prevent group think? This idea of cognitive diversity, not just demographic. And realizing at that time, that Fortune 500 companies were overrepresented.

I’m going to mix the statistics, but essentially, Vernon Jordan and Shirley Jackson were two individuals who were on a number of Fortune 500 company boards. Both were African American, but when you thought about the diversity of the overall Fortune 500 board, it’s like, how diverse can it be if these two people are playing in all of these spaces?

And so, I think for me, going into corporate law was actually a natural extension of, how do you think about the stories that companies tell, whether it’s a venture financing, whether it’s an M&A deal, whether it’s a securities filing, how do they figure out who they are, first of all? How do they get the right people to do the work that they need done? And then how do they make sure they have the right oversight to continue to deliver value to the folks who rely upon them?

And that was, I know this is going to sound very Princeton, but it was actually really intellectually interesting to be a junior associate at a law firm, because you don’t know anything. And law school intentionally doesn’t teach you how to be a corporate lawyer. The bar exam is not geared toward that. And so for me, it was a whole other education.

And I did not love it, and that was hard, because I loved Princeton. I did not love law school. I loved classes that stopped at the law. It was kind of like, I liked anthropology and the law, feminist jurisprudence, sort of the feminist part. And I think I had planned to become, basically wait. There’s sort of a prescribed path. It’s like you wait to go in-house, or you wait to see if you’re going to make partner.

And I was kind of comfortable. I was like, I can do this for a few years. It’s not that bad. But a few things happened. One, my girlfriend at the time, so the one that I met at Princeton, we were still dating. And it had been seven years, and she was an admission officer here at the University, and she was like, “I want to go to business school.” And I was like, “I’m so super supportive. I’m so excited for you.”

And she got into Stanford, and I remember saying, “Congrats. And I’m not taking the California bar.” And so it would’ve been so easy. The law firm I worked for had an office in Palo Alto. We had been together for seven years. It would’ve just been so easy. But there was this very big voice saying to me, “Look at her. She is an admission officer. She’s getting paid a fraction. She’s working just as hard, if not harder. And when you two come home at night and talk about your days, only one of you is really excited.” And it wasn’t me.

And so I said, “I don’t think I can do that. I don’t think I can go.” And she was really supportive. She was like, “You know what? It’s two years. You’ll figure it out. I’ll figure it out, and we’ll come back together.” And so I got on a jump start. I was like, forget partner track, forget going in-house. I got to find something, because once she’s gone, I’m not going to want to come to an empty apartment and be miserable.

And so I started talking to lawyers who weren’t practicing law. I started in higher education, because I was sort of pattern matching. I was like, well, she likes her job, I like universities, let’s start there. Fast-forward, I ended up talking to Leanne Sullivan Crowley, who was the head of HR here at the time, and ended up applying for a role in the provost’s office. And it ended up being split between the provost’s office and the executive vice president’s office.

And it was basically for people like myself, who knew nothing about what it meant to run a university, but who were energetic and willing to learn and willing to help out. And so I did that for two-plus years. My girlfriend and I ended up breaking up during that time, so I was grateful to be back in a place like Princeton, that was one of my own places, too. And in that time, I learned so much about this place.

And as an alum, I now have such profound respect for the undergraduate experiences that we each get to have as a result of this. Your university has to be here longer than any of us. And I guess I’m bringing this up because, at the time that I left, I took for granted that I could always go back to the law firm.

It was 2006. The economy was doing really well. And I remember getting here, and for the first few weeks I almost felt like, I was like, something’s wrong. I’m having so much fun, and I’m learning, and I’m getting paid? Is this a job? Is this a thing? And I kind of quickly forgot that plan of, oh, I can always go back.

Fast-forward 2008, the economy was in a different state. The financial crisis was well underway. I had stayed in touch, so this is another lesson of, there’s something in every experience. Find it, find people. Don’t use them, but understand who they are and get to know them.

And so I’d stayed in touch with people from the law firm, and I got this call. And it was like, “Hey, we’re thinking about a full-time diversity and inclusion role. Would you ever consider that?” This is 2008, audience. It was not DEI, it was DNI. And I was truly sincere when I asked them, “What does that mean? What would I be doing all day?”

And they were really forthright, and they said, “Our chair has decided this is one of the most important things we can do as a law firm in the 21st century. We need to understand how to attract, retain, and advance a diverse set of attorneys who can help our clients focus on the toughest problems that they call upon us to solve.” So I was like, “That’s different.” And I said, “Now, big question, do I have to practice law?” I was like, “Because I’m not an employment lawyer. I’m not going to be a corporate lawyer.”

And they’re like, “No, no, no. We want you to come and bring a different set of expertise.” And so, again, this is for me, this lesson in my career, I’ve had to learn it a few times. But one is, don’t settle for what you think you have to do. And also, be open to what you don’t even know is out there, and bet on yourself. If there are people willing to bet on you, take the bet, and see. 2008, going back to a law firm when they were laying off lawyers, that might not have been the most secure move, when I had found myself here at Princeton. But I said, “You know, I got to keep growing.”

And so, on and on, people can look at LinkedIn. But essentially, fast-forward, that yielded an opportunity to go work at Morgan Stanley, within the diversity function. So not leading it anymore, but being part of a global team. And after a while, I got tired. By 2016, I had been out of law school since 2004, and doing diversity work since 2008, 2009, through 2014. Doing that work, in professional services, and being an employee, with many different intersections in those same spaces, it was draining, it was tiring. And I was beginning to question how much I was getting out of the experience. And so, I remember my wife saying to me, “Well, what do you want to do?” And I was like, “I just don’t want to be here.”

And a lesson my stepmom taught me early on was, “Don’t run away from something, run toward something.” And I got a few calls, I was going way down an offer route, to go back and do diversity at a law firm, and my wife said, “That’s going backwards, Ara. That’s not what you want. You got to sit with this.”

And I was like, “I don’t want to ...” But my wife is very wise, so I listened. And one of the next calls I got was from Audible, to go do a totally different thing. It was to lead employee experience. Audible, I didn’t know it at the time, but my wife did, was a company dedicated to storytelling through audio entertainment. It’s based in Newark, New Jersey, which is where my parents grew up.

It was all of these perfect things. And it was almost like meeting my wife, I had never dared to dream that there would be a professional experience for me. And this was one. And so, I think that that Audible chapter unlocked a whole other bunch of chapters, and brings me to today, where I’m the chief people officer for a health tech company focused on improving the cancer ecosystem and improving the lives and extending the lives of people with cancer.

I’m also on the board of MoMA PS1. I’m the audit committee chair. And then I’m also on the board of advisors for a for-profit owner-operator real estate investment fund. So through all of this, I think I’ve been able to get a few at-bats and learn a few things. But also, I hopefully have been able to teach a few things along the way.

RC: I relate to so much of what you’ve said, in that, I started here, BSE Coase. And I left as having graduated with a degree in the Department of Religion, and certificates in GSS, like gender and sexuality studies and American studies. And so that’s also an intersectionality degree process. And I left, because I loved math. I still do love math, but I fell out of love with it when I was here. And it was just pulling teeth every day. So I was like, I can’t do this. I can’t do Princeton if I’m being miserable.

And so as you come back, as you revisit this space, that I’m sure it holds a lot of significance for you, clearly, why do you feel that having this kind of summit, especially for this affinity group, and then also, why do you feel like that’s important for this time and place?

And then also, you have a pretty important role here in this summit. You’re on a panel, you’re at the book fair. You’re contributing quite a bit, and then you’re also back in this space. So tell me what that means for you and why is it something that, or how is it something that you’ve intentionally re-invited, or come back to over the years?

AT: Yeah. It’s funny, because as an earlier alum, I was graduated. I was like, annual giving, Princeton alumni interviews, I was doing all the things. I was like, this is how you stay involved.

And then coming back to work here, that was a different level of engagement with the University. And by, I guess, my next significant moment here was 2015, my wife and I got married here, the day after the marriage equality decision came down. And I remember just first being grateful to her. She’s not an alum here, but she said, “Ara, we can have our wedding anywhere, but let’s have it somewhere that’s meaningful to at least one of us.”

And she knew from dating me, that this was a very special place for so many reasons. And being able to celebrate our legal union, first of all, by doing it in the Chapel, spirituality is really important to me. And one of the first people I saw when I got here today was Dean Sue Anne Steffey Morrow, who helped me come back to spirituality after feeling like it wasn’t something I could have as a gay person.

So to see her, and just to be able to say, “Look at who I am now, and it’s partially because of you,” that’s important. But the first Every Voice, actually, I think you can fact check me, but in 2013, I remember being on a panel. And I remember taking a picture with Margaret Vendries (*97), and I still have it. And I was kind of conflicted about this one, because Margaret passed away unexpectedly about two years ago. And my wife might not have been able to come, but at the last minute she did. So I was kind of feeling shaky, like what do I do if I’m in this space, and I traveled so many miles, figuratively. What if it doesn’t feel comforting anymore?

And to be here at this, I wanted to be able to create a space for people where I could be someone who was exuding safety and comfort. And so it was kind of scary leading up to this, to be honest. I think I was more anxious about it than I knew. But as soon as I turned that corner, I drove in. As soon as I saw 185, as soon as I just saw the vibe and just remembered, I transported and felt like I’m here now.

The panel being McCosh 50, I have to agree with my fellow panelist, Wade, was not so relaxing, I had macroeconomics there, but we’ll leave that for another time. But I think to your bigger question, it is so important for people to have safe spaces, wherever they find them, however they find them.

And for me, being able to be gay, among all the other things I was while I was here, and I still am in the world, for the University to carve out space and say, “You’re still here and we still want to know what’s going on.” And to maybe hear new voices, I wouldn’t have gotten to meet you.

The circle gets bigger, not smaller. And I think it’s part of being in service of all nations, is to understand how we evolve over time, including as this institution. So I don’t know, it’s really great to be back.

RC: Yeah, I was talking to another alum earlier, about how it’s so different being here as an alum versus being here as a student. I was like, “I feel like my baseline heart rate is just a lot more stable.”

AT: Now try being here as an administrator, and that’s a whole other. Yes.

RC: I was just like, being a student, you have a constant low-grade backlog of things to do.

On the panel, you said something that really stuck with me, because as I’m getting into the world of journalism, storytelling is something that’s so important to me. And you talked about your storytelling work as playing into your coming out process, playing into your connective process, and your self-advocacy process, and all of these things. So what does it mean to you to be here in your capacity as a storyteller? Not necessarily explicitly an administrator, explicitly whatever, but you’re here as a storyteller. Tell me about that. How do you feel?

AT: Yeah. Well, it felt like that was my third coming out, as a storyteller. Right? It was something that I didn’t feel like I could claim it for a long time, until people kept asking me like, “Well, what do you do?” And the through line of all these things that we’ve talked about, for me, has been storytelling.

I think that, being at Princeton in particular, the creative writing program is very strong in my mind and my memory. Edmund White was one of my first professors. I will admit, I avoided taking a class with Joyce Carol Oates because I was intimidated, and had one with Jeff Eugenides instead. But the two books that I am offering today, one is called How to Raise an Art Star, and one is called How to Date a Black Girl.

And How to Date a Black Girl, if it’s anything, it’s almost a love letter to this place. It’s a love letter to, what does it mean for a college or a university to play such a significant space in one’s life, even after it’s long gone? Whether it’s through the love that you lost as a result, the love that you gained, the love that you found, and what does it mean?

But I think, for me, being here is that it’s a really privileged place and space to claim. And I hope that it encourages other folks who are not necessarily the next Toni Morrison, or never will be known as such, but feel the power and the presence that I think her words have taken up for so long, for so many. I think there are so many of us who can do that.

And I think this place is one where there is a strong and deep history and commitment to undergraduates finding their voices, and using their voices, and doing something, and creating platforms. I know I keep saying undergraduate, but I think it is so, so important, even in this age where we all have algorithms telling us how much we are heard or not. But there is always somebody who could hear your voice, or hear your story, and they may never, ever reveal themselves to you, but just by virtue of being in connection with your words, your thoughts, your ideas, you never know what they can do.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

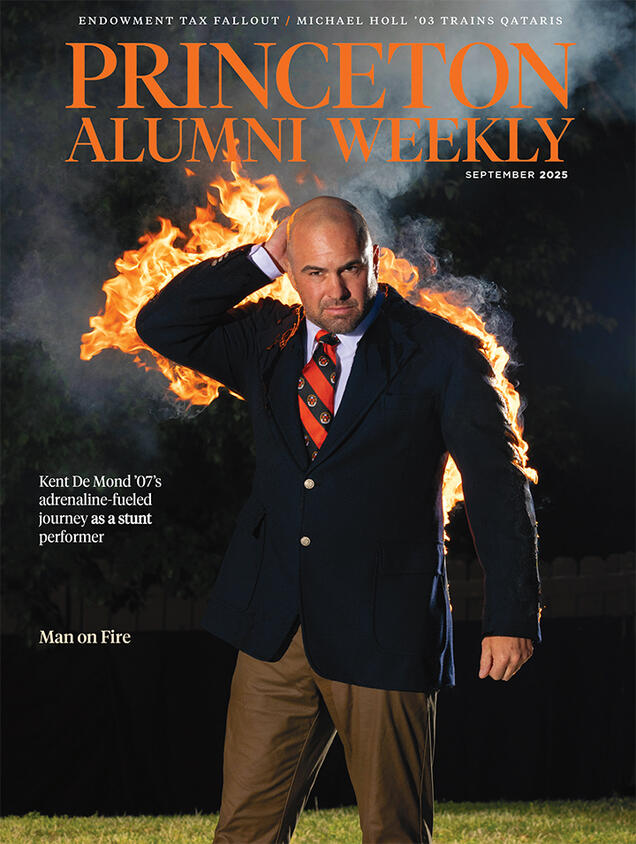

Paw in print

September 2025

Stuntman Kent De Mond ’07 is on fire; Endowment tax fallout; Pilot Michael Holl ’03 trains Qataris

No responses yet