Covering the Strike: Daily Princetonian Staffers Recall the Headline-Filled Days of May 1970

PAW Tracks

May 1970 was one of the most tumultuous months in the history of political activism at Princeton — and one of the most eventful for student reporters. PAW spoke with six Daily Princetonian alumni about the newspaper’s role during the campus strike and related protests.

PAW Tracks is also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

TRANSCRIPT:

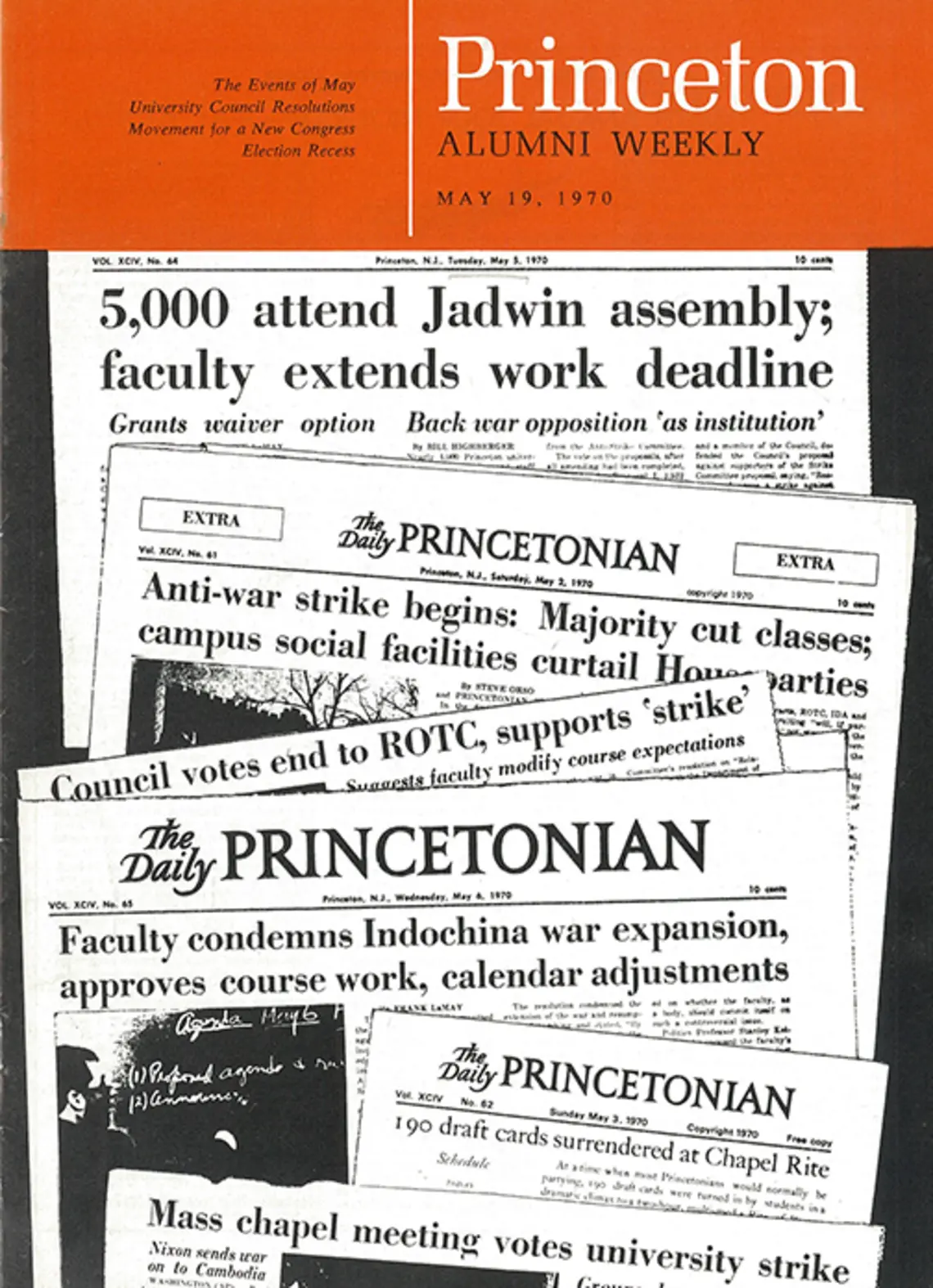

In the spring of 1970, reporters and editors from The Daily Princetonian covered one of the biggest stories in the newspaper’s 140-year history: The campus strike against the war in Vietnam. Protests began almost immediately after President Nixon announced the conflict’s expansion into Cambodia. Four days later, the University community voted to formally oppose the invasion.

Six alumni from the 1970 Prince staff spoke with PAW about their experiences covering the unrest on campus, which began on the evening of April 30.

Richard Balfour ’71: Things took off almost instantaneously, as I remember, after Nixon’s speech announcing euphemistically the incursion into Cambodia.

That’s Richard Balfour ’71, the editorial chairman at the time. As Bill Highberger ’72 recalls, students were wary of what this new phase of the war could mean for them.

Highberger: Candidly, because you had a basically all-male campus — there were so few co-eds that it was functionally an all-male campus still — in addition to the politics of it, most of the men were worried about whether they would be drafted by some kind of an expanded war.

Balfour: The speed with which it all happened, from I think the Thursday night announcement through the strike decision early the next week, was really astonishing. The feeling that everything was happening extraordinarily quickly was magnified to a significant extent being on the Prince, because not only were we absorbed in and participating in the events, but we were writing them up.

Editor-in-chief Greg Conderacci ’71: It was the first time that Princeton really got really, really involved in what was of course then a huge movement against the war. And the SDS had been involved, there’d been demonstrations, there’d been a sit in at the Institute for Defense Analyses, there were a variety of actions, but those had always been pretty much on the periphery. You know, that was SDS, that was radical students, that was the African-American students — it wasn’t viewed as mainstream. What happened in 1970 was very mainstream. It was the entire University.

Prince Chairman Luther Munford ’71: For most of the University community it was a great unifier. I’m sure there were people who didn’t agree with what was going on. But if they didn’t agree, they were not visible at all. There was no counterstrike or protest or people saying, ‘I’m going to class no matter what,’ or anything like that.

Balfour: The series of events had to a real extent radicalized everybody in the University. And by the time that Cambodia was invaded, there weren’t many conservatives left.

In an era before online news and social media, the student daily played a vital role on the campus.

Munford: It’s important to understand that the Prince was the way that people communicated. The official University notices ran in the Prince. So we felt like things were happening, that we needed to report, and in fact we put out a broadsheet Saturday edition, which we’d never done before, and we even put out a Sunday morning edition that was just one page that we went over to the creative arts building and hand set the type, letter by letter, to put that just one page together, so people would know what was going on and what was planned and keep up with it.

Why would a student newspaper turn to manual printing? Well, as Conderacci tells it, Larry Dupraz, the Prince’s compositor, was exhausted after putting in extra hours on the Saturday edition and serving as a volunteer firefighter in town as well.

Conderacci: When Larry said he couldn’t function anymore, the only way that we could produce a newspaper was to individually hand set every single word in moveable type.

Highberger: So I had taken a class in letterpress printing and everybody on thePrince knew how to set type, because you had to set headlines by hand to be on thePrince on the news side. So I did have a team of people who knew how to set type from California job case, and I had used the print shop at 185 Nassau Street as it was then called because it was sort of the visual arts program for the Princeton students, and I knew the equipment there because I had taken a class either that semester or some earlier semester and basically we figured out how to break into it. We went around — to my memory, we didn’t have a key — but one of the windows was open on the outside and you could sort of climb up like a cat burglar. And so we got ourselves inside the print shop and that’s how we printed the special issue. Gutenberg would have definitely recognized what we were doing.

Conderacci: For me that was kind of our finest hour at the Prince, during that board anyhow. Probably what I’m most proud of.

Reporter Steve Massad ’72: Who knows how many people were really reading things as seriously as we thought we were writing them. But to us it was a big deal and we took it very seriously.

On the editorial page, the newspaper’s stance was clear.

Balfour: The anti-war orientation of the Prince by this point, the spring of ’70, was of long standing.

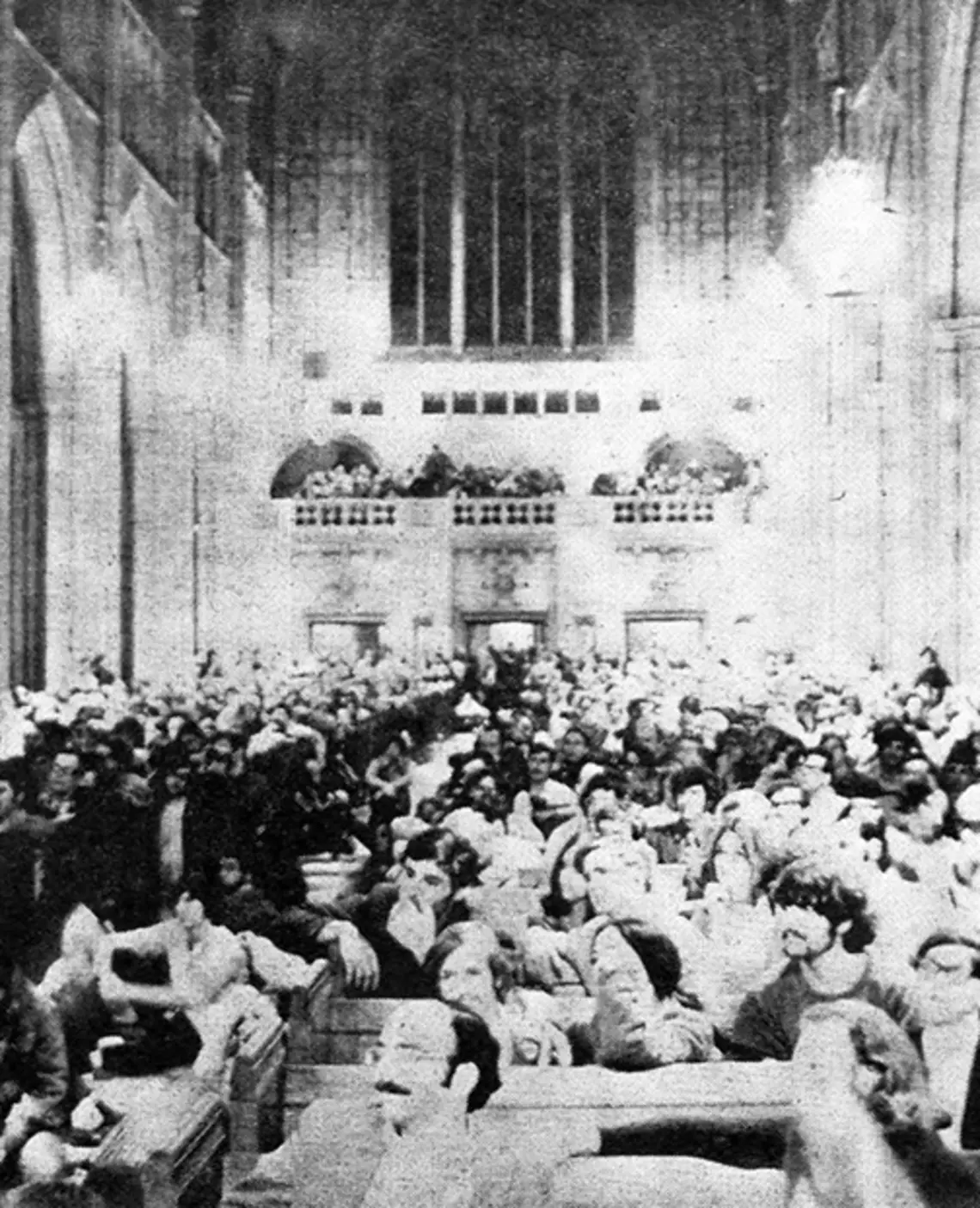

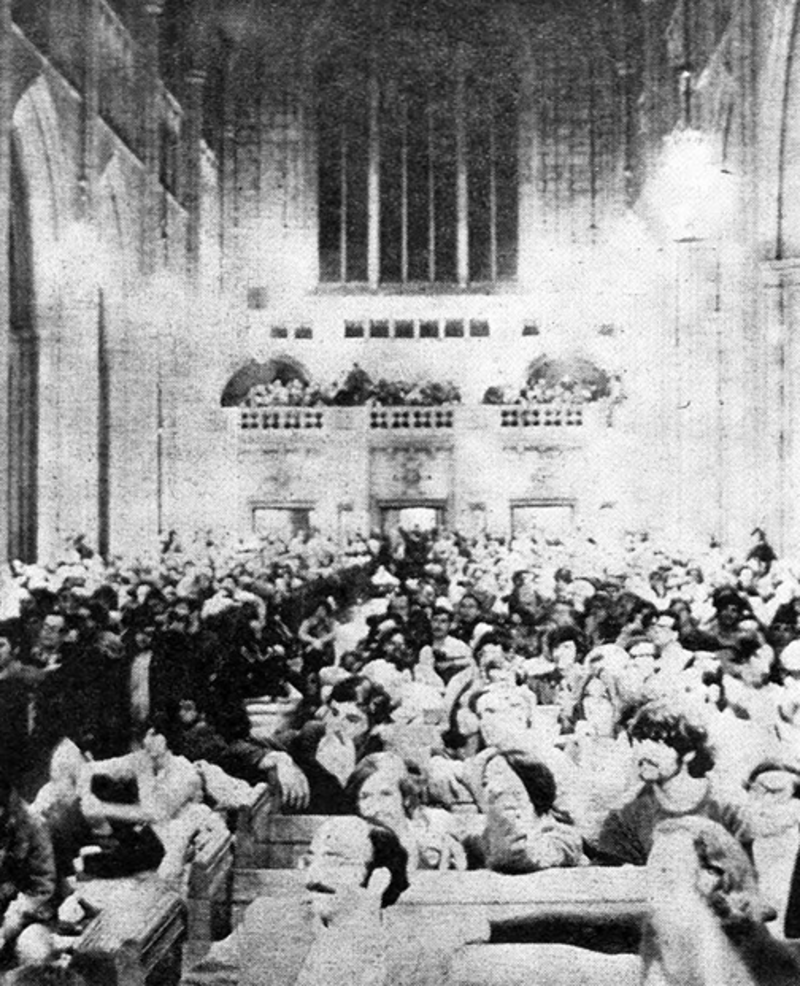

At the protests, Prince reporters tried to maintain a sense of professionalism. But the line between journalist and participant sometimes blurred. Photography editor Bob Prichard ’71 shot photos while taking part in the student meetings in the University Chapel.

Prichard: Dean Gordon asked people to hand in their draft cards. I don’t know whether it was that meeting or very soon after it, but I handed in my draft card, which at that point was considered a crime in the midst of the strike. People of that era were to carry their draft cards with them all the time. The draft board got those draft cards and I suppose could have arrested all who handed their draft cards in in that service, but what they did was they sent them back in the mail about six months later saying, you seem to have misplaced this, we need to remind you that according to U.S. law you need to have this card with you at all times.

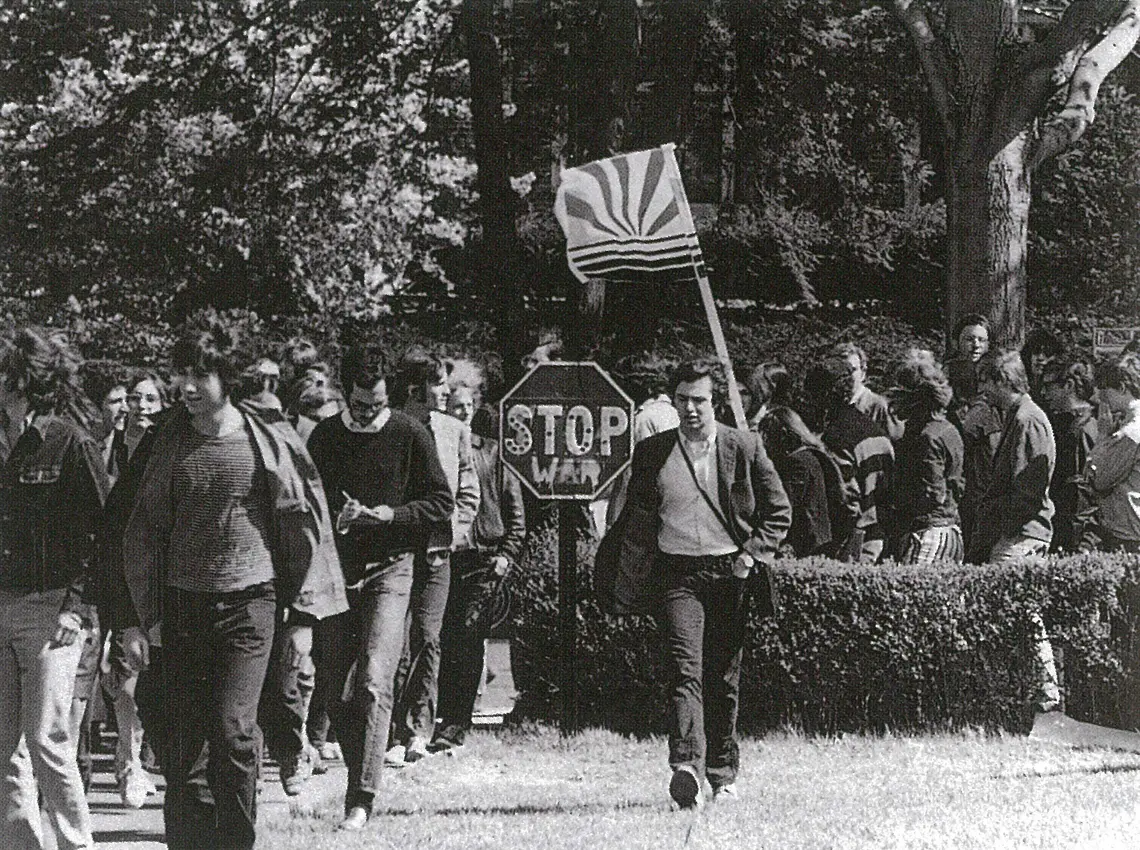

Munford: There is picture of a march on IDA and right in the middle of that picture is a Viet Cong flag and right in front of the flag is me, and all I’ve got to say that is that I am delighted that it is obvious from the picture that I was taking notes as a reporter while I was in that line of march [laughs]. That’s a juxtaposition of being a reporter but also in some sense being in the march.

At a community meeting in Jadwin Gym, students and faculty formally voted for a strike against the war. WPRB broadcast the forum.

WPRB: The non-official result of those supporting the first resolution is 2,066 and on our last vote we had over 3,500 persons voting so in the case that everyone votes only once, which is the intent of this assembly, this resolution, resolution number one, would receive support as the most popular resolution considered by this assembly of the Princeton University community. And I have the word that this tally is official: 2,066 persons supported it. There’s something else going on over on the other side of the party that we can’t even see at the moment. … And a chant strike, strike as you can hear in the background.

When classes ceased, the Prince kept publishing for two and a half weeks before the staff began leaving campus for the summer break.

Massad: We finished on campus in May. I personally hopped in a car and drove off to far west Texas for a job working in the oil fields. And it was surreal to go from a Princeton campus on strike to that job where nobody had ever heard of Princeton, let alone the strike.

Munford: I went and worked at the Washington Post. They put me on the foreign desk and my job was basically capitalizing copy, that came in on the teletype in those days. That led in turn to an incident the next January, January of 1971, where some of the people who had worked at the Post together as summer interns and other college editors got together to visit at the State Department to talk about the war and find out what we could and express our opinions. And President Nixon found out about it, and invited us over and we actually met with President Nixon in the Oval Office. And we then started asking questions about Cambodia, and when was the war going to be over, and other things that were not designated topics of discussion, and that was that. It was very pleasant, but we actually ended up face to face with the president of the United States, indicating we were anxious for the war to be over.

For Balfour, a native of Canada, the period was an admirable era for the United States.

Balfour: I think, myself, this period was a great period for America. I remain of the view that the Vietnam War was a terrible mistake and in that sense America had committed it. But I think the right way to view what went on in the ’67-to-’70 period was something quite different. It was America recognizing that it had made a mistake and coming to grips with it, which is a much, much harder thing to do. It’s one of the hardest things in life.

Massad: Looking back, I think people had different views of how significant it all really was. But at the time, it was extremely dramatic to all of us and everybody on campus. Everybody was caught up in it, whatever their view of it on the merits — they were caught up in the drama that was going on.

Conderacci: We had an amazing experience that I’m sure anybody who lived through it remembers it. And it’s four decades ago. And there’s some things that happened that I remember like it was yesterday. I can assure you that I would not have that memory of any sort of courses that I took that semester. So it was a great lesson, I think, for all of us at the Prince, but I think also for anyone who was privileged to be at the University at that time.

Paw in print

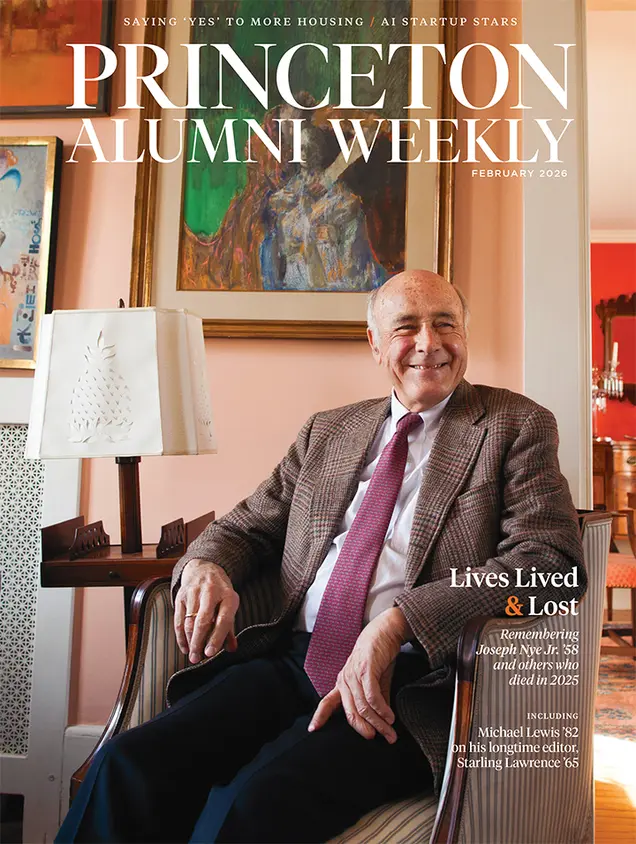

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet