Lives With Meaning, Wilson’s Legacies, and the World’s Best Athletes

Rally ’Round the Cannon Podcast

In this episode, we talk about some of the multifaceted contributions of alumni featured in our Lives Lived and Lost issue, Gregg explains the approach he took in examining how Woodrow Wilson is memorialized on campus, and we ask a question about Princeton athletes who’ve ranked among the world’s best in their sports.

The Rally ’Round the Cannon podcast is also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

TRANSCRIPT:

BT: I’m Brett Tomlinson, digital editor of the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

GL: And I’m Gregg Lange of the Great Class of 1970, who should know better.

BT: And this is the Rally ’Round the Cannon Podcast, a look at Princeton’s history and the people behind it. The February issue of the magazine, keeping with recent tradition, features our annual Lives Lived and Lost package, appreciations of 10 alumni who died in the last year. In it are names that may be familiar – Nobel laureate John Nash, Princeton squash coach Bob Callahan – but also many you may not have read about before. Gregg, you’ve had a chance to look at the pieces. Were there alumni in the issue who stood out for you?

GL: Well a whole slew of them, which is why it’s so tempting to spend an hour talking about them here, which we won’t. But I knew Don Oberdorfer, the great writer and editor who, among all of his other accomplishments in the private sector, wrote the 250th coffee-table book of Princeton, which is just a magnificent illustrated volume. And there are other people that I was personally less familiar with that I find endlessly fascinating.

One person that I knew about and knew about for years was Bob Curvin *75, who got his Ph.D. in politics at Princeton and was a legend in the city of Newark, going all the way back to the riots of the ’60s where he had first of all cofounded the CORE chapter in Newark, and tried to calm everything down and failed – but gained huge political influence in the city as a result. And who, subsequent to that, chose for his career – a lot of which was in New York City – to stay in his home in Newark and to fight the fight for community development there, speak out at every opportunity, and was an absolute living legend in northern New Jersey.

I think it was while he was at the Ford Foundation in the early ’90s that I tripped across some of his writing on urban policy – he was the Ford Foundation’s director of urban policy initiatives at the time – and it was only then that I found out he had a Princeton Ph.D., which astonished me, given his long activist background in Newark and his close association with Rutgers-Newark, which is where he did his undergraduate work. The more I found out about him then and subsequently – it’s fascinating the way his personal life and career took two very different tacks simultaneously, back and forth on a daily basis: He lived in Newark, he was part of the community, he was part of activist initiatives there for 50 years and did that every day; meanwhile, he spent years on the editorial board of The New York Times, he was a dean at the New School for many years, he had this influential policy job at the Ford Foundation for many years, and did this huge stream of writing. And for someone to live so actively in those two worlds, simultaneously, and to have the kind of impact he did, is both a stunning accomplishment and I think in many senses a tribute to Rutgers-Newark and Princeton, who trained him astonishingly well to handle those kinds of issues. To do that for 80 years is an extraordinarily draining experience. He did a magnificent job – very, very astonishing life and I urge people to go back and look at many of his writings.

Meanwhile, I found a strangely parallel story in Nancy Sullivan ’80, who died unfortunately in a car accident in New York state. She was an art major at Princeton, and I think in these days of careerism and applied everything, there’s probably a whole school of thought out there that thinks art majors aren’t work the paper they’re printed on, much less spending the resources to generate them. But here is someone who, at 30 years of age or so, goes over to Papua New Guinea and develops this magnificent humanitarian life with the native tribes there after further training as an archaeologist, and becomes this living archaeologist, with the population on a day to day basis, trying to help protect them from the intrusions of civilization – the rampant intrusions, I would say – and at the same time, she is documenting and publishing works on 20,000-year-old cave paintings throughout the island, and the history of them and their cultural and historical meanings. The idea that again, these two completely different levels can exist in the same person simultaneously on a daily basis, someone who lived for 24 years in Papua New Guinea and was studying cave paintings in the morning and doing government testimony in the afternoons, trying to prevent intrusions on the native lands – that a place like Princeton can generate those kinds of people, that are that comfortable, that well-versed, and that active in all those ways, is an extraordinary lesson to be learned, both from Nancy and from Bob Curvin. If they’ve inspired two people each – and they’ve inspired many more than that – to do even half of what they’ve done, they left the world a better place. And you know they did. That’s a meaningful thing to think about when you read these kinds of memorials. I think it’s a magnificent part of PAW. I don’t think it’s backward looking at all, I think it’s forward looking. You look at people like this and you say, what can I do? Or what should Princeton be doing? And I think that there are an infinite number of lessons to be learned.

Speaking of which, you’ve mentioned John Nash. We certainly won’t go over his story again because people are aware of it, but I would point out that the short piece in PAW is written by Sylvia Nasar, his biographer, who wrote the book A Beautiful Mind. And if there are folks out there who’ve seen the movie, which was a wonderful movie but certainly a very artistic interpretation on a life, who have not read the book – read the book. It’s one of the great biographies of the last 20 years, it’s magnificently done, it makes you understand exactly what was going on with Nash before, during, and after all of this, and really makes you consciously appreciate the efforts that people like Nasar and Harold Kuhn of the math department and the entire Princeton math community did to keep John Nash away from the edge during the dark years and to stick with him through the bright years at the end. It’s a deeply moving story, it’s a magnificent book. If you’ve seen the movie and not the book, that’s fine for right now. But let me tell you to go do it.

BT: Well Gregg, you certainly give us lots of reading recommendations, and I think we have a lot to catch up on between episodes.

GL: There will be a test in May.

BT: For the staff, it’s a group effort to put together the Lives issue. I was able to do one of the pieces this year, and it’s great fun to see all the pieces come together and tell this diverse narrative of Princeton. It really is people who have done such a variety of meaningful things with their lives after college. It’s certainly become one of my favorite issues. I hope that the readers enjoy it as well.

GL: I would think that the horrendous part would be trying to trim it down to 10.

BT: And that luckily is not my job, it’s the job of our editor, Marilyn Marks *86, and this year she’s done a great job again, picking a nice selection.

Gregg, moving on to your online column this month, it takes the form of an open letter to the Wilson Legacy Review Committee, a bit of a departure but also I think a worthwhile one. How did you approach writing this column?

GL: It was intended to be narrow than you might think. I limited the breadth of the letter to Wilson’s legacy itself, and the committee has asked for more general comments on how individuals should be memorialized at Princeton, not to mention other issues. I did stay away from that a bit, but I tried to emphasize what Wilson had to do with Princeton as distinct from a lot of the other aspects that have been discussed about him, and in some cases if you downplay his role in world affairs, that strengthens his case, and in other cases it weakens his case. There are many moving parts. But I talk about, of course, the Wilson School; I talk about Wilson College; but I also talk about the Woodrow Wilson Award, which seems to have gone by the wayside here, for whatever reason, in terms of discussion, and I regard as one of the more important issues to be discussed in terms of his legacy. I do urge everybody to go and look at the column.

At the same time, and this was being written in parallel, in the new issue Deborah Yaffe has a piece in which she encourages people to supply their own comments to the Wilson Legacy Committee of the trustees. She goes through the background in much fine detail about Wilson’s history, and in the midst of that she talks to a number of historical authorities who are well worth reading every word of – it’s a wonderfully researched piece with some marvelous thoughts in it. There’s one quote in there that just hit me like a thunderbolt. From the great retired Princeton history professor Nell Painter, in reaction to the question of why Wilson has arisen now:

“ It’s all about the questions we ask. The questions have changed. … I mean, the questions always change. That’s why we keep writing history.”

It’s so natural, it sounds like a truism. It’s not a truism – it’s an extremely deep and complex idea that everybody listening to this should turn over in their minds a bit and think about why the way we look at things keeps evolving, and hether in some cases that’s for better or for worse. It’s an extremely powerful thought. I’m actually going to use it as a jumping off point for my next column. But it’s very important to consider in the context of Wilson, and I urge people to do that when they’re considering this in the next couple months.

The other thing is, I you want to go talk to the Wilson Legacy Committee of the trustees, they’re taking appointments. So go talk to them – it’s a great group of people and you’d be very pleased if you did.

BT: Yes and you can find information about the available times on their website, wilsonlegacy.princeton.edu.

GL: Exactly. There’s a whole outline of other things that have gone on, and they’ll be posting other comments along the way. My open letter will go to them through that website at the same time the column drops. Take your shot, go talk to them.

BT: We are now into 2016, which is a summer Olympic year, and as we get closer to the Olympics, we’re going to talk more about Princeton’s remarkable Olympic history, but it’s worth mentioning here that Ashleigh Johnson, the women’s water polo star who was featured in our January “Road to Rio” segment, was recently named the world’s player for 2015 in her sport – congratulations to Ashleigh, truly a remarkable honor.

GL: Not the best junior player, or the best college player.

BT: Or the best American player.

GL: The best women’s water polo player in the world.

BT: And that, Gregg, raises a question that you mentioned to me.

GL: I threw it on the table and said, OK, I give up and I don’t even know how to go about researching it, but I want to know if someone out there in vast beyond can come up with another Princeton athlete who has, at some point, been named the best athlete in his or her sport, in the world.

This is harder than you might think. Bill Bradley fans, as an example, you might try to say that his gold-medal captaincy in the Olympics in 1964 put him in the running, and it certainly might have. The only other thing that I could come up with, off the top of my head, was Hobey Baker prior to leaving for France in World War I was probably regarded as the best ice hockey player in North America, but whether that equates to world domination at that stage is an interesting question.

I want to know what other Princeton athlete, at any other point, has been the best in the world – in like a Tiger Woods sense, or in this case Ashleigh Johnson. I’d really be fascinated. If you’ve got an answer to that one, dial us up.

BT: It’s a great question, and we’d love to hear if you have an answer for us atpaw@princeton.edu. You can email us if you have questions or topics for future episodes as well.

GL: Or for those in my generation, you can always send a post card.

BT: That would work too. Well, I think that brings us to the end, Gregg.

GL: Absolutely – I look forward to some feedback on all of this, and as always, we remind you that Rally ’Round the Cannon is a podcast from the Princeton Alumni Weekly online.

Paw in print

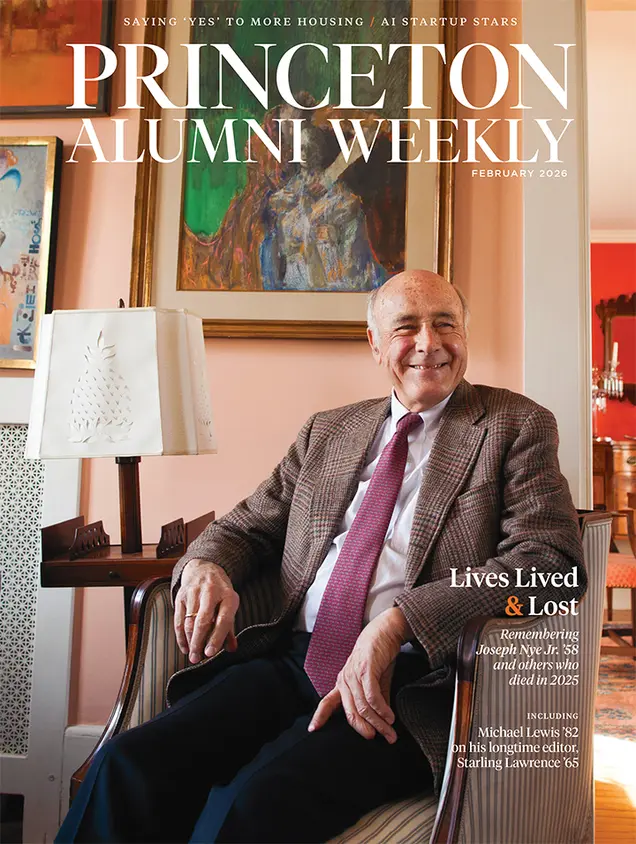

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet