May has us thinking about Reunions, and two of this year’s “major” classes: the 50th reunion class, 1967, and the 75th, 1942. Both left college in a world that was much different than the one they’d known as freshmen. Also in this episode, we talk about Gregg’s new column on free speech at Princeton and Gregory Heyworth *01’s use of imaging science to restore damaged documents.

The Goin’ Backstory podcast is also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

TRANSCRIPT

Brett Tomlinson: I’m Brett Tomlinson, the digital editor of the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

Gregg Lange: And I am Gregg Lange of the Great Class of 1970, who should know better.

BT: And welcome to Goin’ Backstory, our Princeton history podcast. Gregg, I had a nice conversation earlier today with a member of the freshman class who is writing his final project for a journalism class about a bit of Princeton history that we’ve mentioned before: the admission of J.D. Oznot, who was not — a fictional applicant born, appropriately, on April first, and admitted with the Princeton Class of ’68. It was nice to hear that there are students out there still interested in that story, interested in classic Princetoniana, and it sounds like he’s done some great research. We certainly wish him well as he writes up that story up before Dean’s Date.

GL: Very kind of you to mention that he is not a member of my grandchild class. Because that would be obnoxious. I’ve met a number of the freshmen in connection with class coordination with the Class of ’70, and there are a magnificent group of — I would call them kids — half of them seem to be bigger than I am, I think the football team must have gotten some good recruits but anyway. Men and women, I don’t know what that means. But at any rate, good to see them involved in something like that not to mention the interesting history, because they were involved in it, in the admission of our friend Joe Oznot, with the Class in 1967, which at the P-rade this year will be one of the most honored of the groups in the grand march because they are the 50th reunion class this year. You think you think I’m out of sorts now as a grandparent, wait till you see my 50th reunion.

BT: This is our May episode, which means Reunions is right around the corner. Time for you, as the P-rade emcee, to start gathering material to fill the running commentary at the reviewing stand. I feel like I’m setting you up for a Lake Wobegon comment here, but are there any classes that stand out for you, among this year’s major-reunion classes?

GL: You know ’67 is a great place to start. In part because not only do they have a real major reunion — 50th reunion, for those of you who are younger, used to be the cut off point for the old guard, before grade inflation took hold. Now you don’t make the Old Guard until your 65th reunion when you’re like 87 years old and really getting up there. It used to be at the 50th, but there just got to be too many in the Old Guard.

At any rate ’67 is one of those transitional classes which I think sometimes we emphasize not enough. You have to put yourself in their place and figure that they started at Princeton in September of 1963, three months before the assassination of John Kennedy. And then while we were undergraduates watched the emphasis on the Great Society, the passing of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, the construction from essentially nothing of Medicare, by far the most transformative social program in the United States since Social Security, and then in turn even before they graduated started to see the specter of Vietnam looming not only on the horizon but really advancing at them. There were — I was sort of fascinated to figure it out — there were 82,000 men drafted in the United States, which was the major way of stocking the armed services in that era — 82,000 men drafted in 1962. In 1966, the year before this gang graduated, there were 382,000 drafted, almost five times the number and clearly the country was starting to wind into a very nerve racked form from which it really only recovered in the mid 1970s. ’67 had to live through all that stuff in almost an instant because when you’re there for four years on campus days seem to fly by; you never have enough time for sleep, everything else was going on. And the world literally changed between the time when they stepped on campus in the day they graduated. That can be a very disorienting kind of feeling that can have an effect for years on classes; ’67 is a very very close class, and I think they reflect that in many ways.

And then if that’s the case, I was really giving some thought for a number of other reasons to a couple conversations I had recently about the Class of 1942, which is this year’s 75th reunion class. Now again if you do the math, that means most of these people are over 95 years old. There are still 37 of them who are alive, which is remarkable in itself. They’ve always got a passel of people back at Reunions, although again the age inflation has pretty much ensured that nobody from ’42 will win the Class of ’23 Cane for the oldest returning alum this year. We should think of it in context that the first time a Princetonian returned for their 75th reunion was only in 1961. The school went through well over 200 years before that even happened the first time. And now in the 75th reunion class we have 37 people alive at their 75th. I would bet you that eight or 10 of them at least will be back, very possibly more. There were more than that, over 20 as I recall, for their 70th.

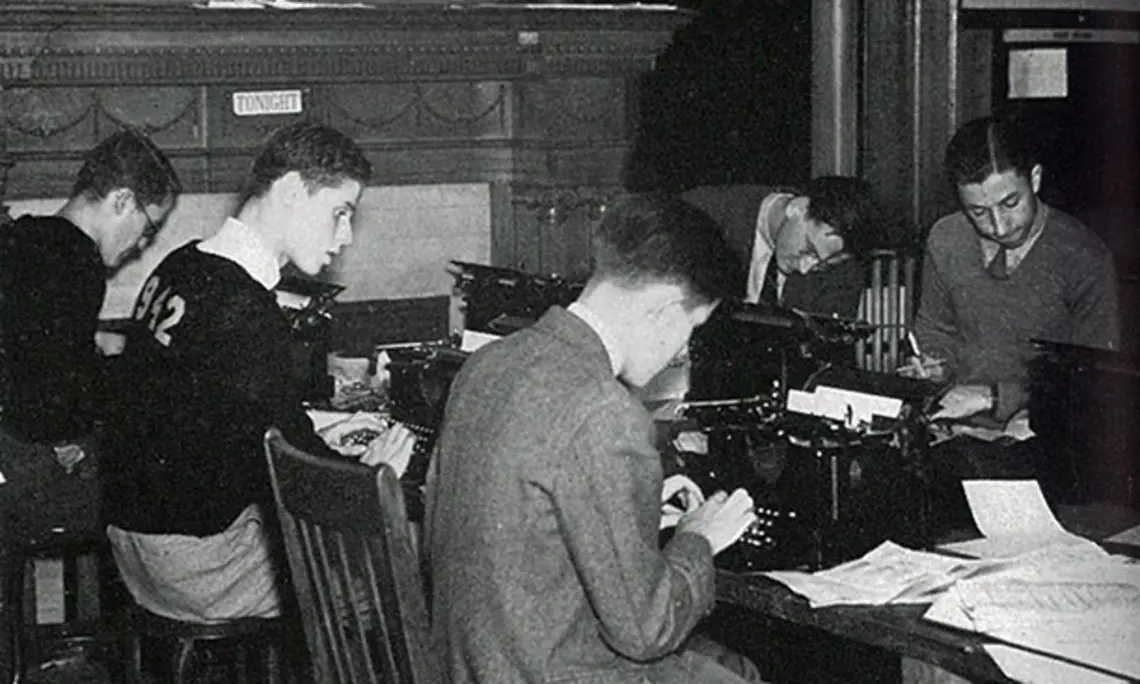

Now this is a class that entered in 1938 in the middle of the second wave of the Depression, that one year in witnessed the beginning of World War II on September 1 of their sophomore year. Six months before they graduated was Pearl Harbor. And they turned out to be the last traditional four your class that entered in their case in ’38 and graduated in ’42, until the class 1949, seven years later. All the classes in the interim had people on accelerated courses graduating early leaving before they graduated to go into the service, coming in, going out, appearing in vanishing for semesters here and there. The Class of ’42 went through their regular four years and then 83 percent of them ended up in uniform during World War II. Twenty-five of them died in action. And this is a world that’s so different from what we experience on a day to day basis that it’s really difficult to describe to people. They’ve lived through it, they’ve triumphed over it, they’ve worked around it, and they’ve done many many great things, far too many to mention. In terms of the classmates of that wonderful class, even includes my roommate’s father who was a meteorology professor at Penn State after he got out of the service. It’s wonderful to see 37 of them still around hopping. I don’t pretend that I will be at age 97 and it’s great to see them back for their 75th reunion as part of the Old Guard.

BT: And I think it’s a common experience for individuals to come into college and, you know, over the course of four years kind of leave quite different than they were as freshmen. But as you say it’s not always the case that classes enter in one world and graduate in another, and those are two examples where the changes are just so profound and really interesting to think about.

GL: And the ’60s are a much more subtle set of questions than World War II or World War I or the Civil War certainly, but in terms of the abilities of individuals to come to grips with what’s going on around them it is certainly just as just as traumatic and just as thought provoking.

BT: Moving on to another topic — Gregg, you have a new column online and it relates to free speech on campus; coincidentally, the May 17 issue includes an interview with Anthony Romero ’87, executive director of the ACLU, in which he talks about what he views as troubling trends on college campuses in terms of how visiting speakers are treated and how students approach viewpoints that challenge their own views. In Princeton’s history, what have been the guiding principles when it comes to campus speech and guest speakers in particular?

GL: Well the sort of gold standard, which developed very early on, is that if a bona fide campus group — and it can be a fairly modest group, not always Whig-Clio or some faculty department or whatever — if a bona fide campus group invites someone to speak to them on campus, either as a private or public event, that is honored. There have been kerfuffles over it, and I talk about a few of those historically, although I should say that all in all Princeton has been spared from some of the worst of these adventures historically in part because of the embodiment in one person of the very idea of American free speech, and that’s Norman Thomas of the Class of 1905, the great Socialist of the 20th century in the classic sense and someone so respected throughout the campus not to mention the country, that whenever anybody invited him on to speak, and he loved to come back he was at every reunion he could possibly make, adored Princeton for all of what he perceived to be its flaws, that he was a one-man free speech army. He would come in and speak about unions, he’d come in and speak about urban housing, he’d come in and speak about minimum wages, he’d come in and speak about anything and everything. And everyone would show up and everyone would listen attentively to him. It actually created an aura that made Princeton a real bulwark of free speech without actually intending to be although it’s always been part of the formal policy of the place. People really have not abused that much over the years at all.

In recent years, and I tie this in to the column recent efforts highlighted in PAW the end of last year I know as well by professors Robert George and Cornell West on the right and the left who who deeply respect each other and of co-taught courses, to encourage every kind of responsible free speech on the planet. [They] have been sort of a voice crying in the wilderness and some of the craziness going on on college campuses these days. They tied directly to what Anthony Romero is talking about in his question and answer with Mark Bernstein and it’s really the driving reason why I wrote the column. It ties in very much with the historical stances of Princeton. Many alumni know either because they were there or from reputation about the Alger Hiss speech in 1956 and the George Wallace speech in 1967, both of which went on unimpeded after a lot of who do beforehand and even afterward. But I don’t think we can possibly overstate how much Robbie George and Cornel West have done in a positive sense to really set the bar for a current day interpretation of what free speech is and what free speech should be. And I also would say in passing that the current statement at Princeton in Rights, Rules, Responsibilities, the student and faculty guide book, is brilliantly stated, unbelievably clear, and very much in line with what I would with what George and West are teaching, and everybody should read it, think about it consider it historically, as I did, which is a lot of fun and makes you think about, you know, arguments around the water pump over the issues of the Civil War not to mention what’s going on today and then really give some understanding to what free speech is why it’s so challenging and why it’s so important.

BT: And it’s a good column because it makes you realize that, as you say, these issues are most important when they’re the most difficult. I definitely encourage everyone to read that one. I encourage everyone to read all of Gregg’s columns — they’re all great — but this is really timely. It’s a nice thing to reflect on and respond to. We always welcome comments on the site and I’m sure Gregg would love to hear from you as well.

GL: Vote early and often.

BT: Before we say goodbye, we should mention one more story from the May issue: Gregory Heyworth *01 and the Lazarus Project — the subject of a short feature piece. He’s using imaging science to restore damaged historical documents. And while this isn’t Princeton history, it’s a remarkable project in the larger world of history and one that seems to have tremendous potential. I know it was a powerful read for you as well.

GL: You know just what we’re talking about this I think to the column I did a couple years back on Toni Morrison’s notes, which was an issue that the Princeton Archives were deeply involved in. And that was, interestingly, an entirely different world because that was simply original material from her various drafts of some of her major novels that happened to be on outdated computer disks for which for which new interpretive software actually had to be built so that research could be done on her original work on various interim versions of her of her writing.

But that is very much the same question as what Gregory Heyworth is dealing with — he’s a classicist by training not a not a computer scientist at all, or alternatively any kind of a historical researcher. But he’s going back and trying to look at original documents from — and hold onto your seat —the fourth century A.D., and finding various overwritten things, various things that have been soaked in all kinds of liquids that we don’t want to know about, various things that have been involved in wars, and desert storms and who knows what, and people are trying to find various scientific ways to honor uncover in terms of their original meaning. And what these both emphasize is the crucial importance historically to original documents. And when it comes right down to it, and we live in a world of the web with an infinite number of interpretive statements on all sorts of truisms and false-isms as we’ve figured out recently, and the import of the original materials of where these ideas and issues and people come from becomes even more important as they become more covered with layers of interpretive history.

And if you look at it not as a biochemical adventure but as something in the quest. Of people to try and come up with true meaning, to where these ideas began, it becomes this gigantic mystery story that is just riveting, almost every day in almost every way.

I thought Josephine Wolff ’10, who wrote the article on Gregory Heyworth, did a magnificent job of showing that, but it extends to so many different kinds of platforms and issues and ideas and interpretive fields in this day and age, that is almost hard to grasp. You have to sort of sit there and think about all the ways in which that’s important. You realize how immediate these things can be, and how important they are to the quality of how we live our lives.

BT: We like to think that history matters than, and certainly it does in these cases. Gregg, I think that that wraps it up for the May episode. I look forward to seeing you at Reunions, and hopefully some of our listeners as well.

GL: Absolutely, and we’ll report next month on precisely how many people wander down to the P-rade, because as we all know it never rains on the P-rade.

BT: Don’t do that — don’t jinx it.

And we remind you that Goin’ Backstory is a podcast from the Princeton Alumni Weekly online.

Paw in print

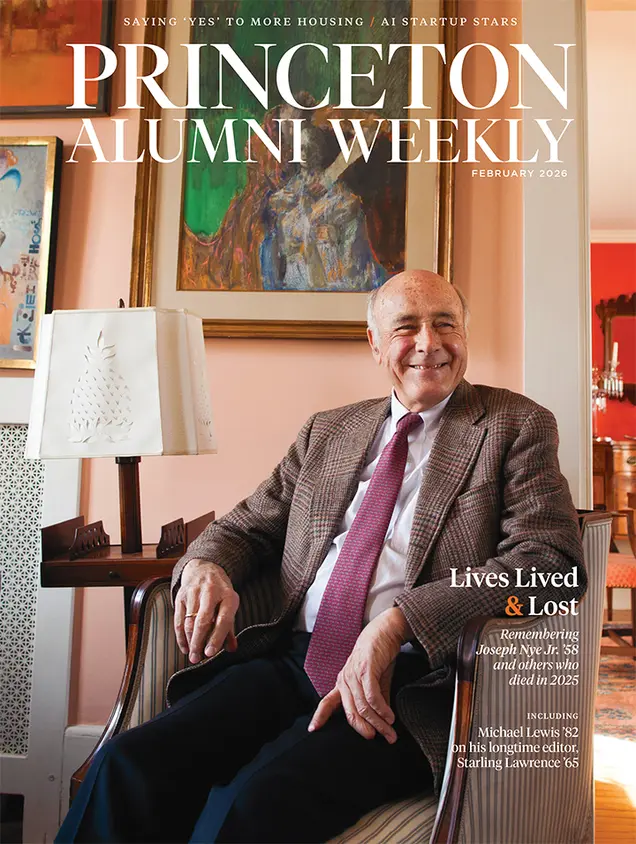

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet