Zien, who arrived at Princeton from Milwaukee, Wis., majored in philosophy and moved to New York City after graduation. He is the founder and president of Business Logic Inc, a consulting and software development company, and for the past six years has been the treasurer of the Class of 1971.

PAW Tracks is also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

TRANSCRIPT

Brett Tomlinson: The campus protests in late April and early May of 1970 marked one of the most turbulent periods in Princeton’s history. Following the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, Princeton students joined others across the country in demonstrating against the war in Vietnam — a nationwide clash that would include the killing of four students at Kent State by members of the Ohio National Guard.

At Princeton, students discarded draft cards at the Chapel and picketed the Institute for Defense Analyses. University officials eventually ended the spring term early, in response to the student strike. But before that, students had to make a choice about whether to attend class during the protests. That was the case for Howard Zien ’71, a junior studying philosophy at the time. His decision to go to class led to one of his most vivid memories of Princeton.

Howard Zien: The student draft was a looming and alarming presence for me and many of our classmates so there was a quite a bit of campus unrest. It was in Wisconsin, it was in Berkeley, it was in Columbia, and it was, as we say, even here: Princeton was — the students here were quite agitated and there were demonstrations, I think my junior year in particular. They actually suspended classes, ultimately.

The vivid memory that I have is in the spring — I was walking towards my class in McCosh on that diagonal walkway, and there were students, large numbers of students, on both sides of the walkway, waving and shaking their fists and jeering and shouting, you know, don’t go to class. I think that there was a, like a rhyme or a chant that they were doing but I can’t remember that. But I just remember the anger, and my feeling was, “Hey fellas and girls, I’m with you, I agree with you but I also have to go to class.”

I was on board with them. It wasn’t like I didn’t understand the issue. I was with them. I just also wanted to go to class. But you only got one checkbox, you know, you didn’t get to do both. So that’s what made it difficult. And maybe I respected and admired them because maybe they were saying, “I don’t care what happens to my education, to my future — this is really important, this is here and now.” So there was no — I didn’t have any animosity in that sense towards them. I maybe had some shame, because I didn’t have the conviction to be on the other side of that sidewalk, of that issue.

The amazing sort of observation at that time was that there was no equivocation, there was no negotiation, no discussions. You were on one side or the other, but not both. So if you’re walking on a sidewalk, you were for everything they were against. And if you were shouting and yelling and shaking your fist, you were on that side of the of the issue. And the reason that that was so important, that it’s something I’ve never forgotten, is that throughout the world sometimes peaceful demonstrations [and] sometimes violence, you know, folks pointing guns and shooting at one another, [have] this idea that there’s no middle ground. In so many parts of the world, you’re on one side or the other and there’s no sort of way to sort of straddle the issue, and that was a realization that recurs all the time when you see videos on TV or when you read the newspapers. That was really a profound experience that that I had here and that I remember quite vividly.

You know when things get incendiary, you have neither discussion nor debate. It’s statements, it is demands, it is this-is-the-way-it-is, this is how we see it, you sort of turn off your listening mechanism, and I get that because these were — we’re talking about people’s lives, their futures. People were expecting to leave the University and, you know, go to boot camp. So it was a very personal visceral issue. And Princeton is, I guess — the reason that I before I said before that it happened “even in Princeton” is because we’re somewhat sequestered here. It’s kind of bucolic, it’s beautiful, and you lose track sometimes of the real world so to speak. So the fact that it hit here is because people related to the draft and the war in such a personal way, and I will tell you that if we had the draft today — and I have a son who is 25 years old now — but if we had a draft today I’m certain that we wouldn’t be engaged in the Middle East, in wars there for 10 years, 11 years. I mean, the idea of a draft, I think, makes everybody connected to war and peace in a more personal way.

I come to many campus events — I’m class treasurer. I see many students, the young ones, and they have no idea. You know, they could read about this experience, but that walk on McCosh walk, they’re not talking that walk. I did. So they have no idea what it was like to be here in that situation. Because they just don’t have that same pressure experience. They have academic pressures, but not these other kinds.

But they love hearing the stories when I tell them.

BT: Our thanks to Howard Zien for sharing his story. Brett Tomlinson produced this episode. The music is licensed from FirstCom Music.

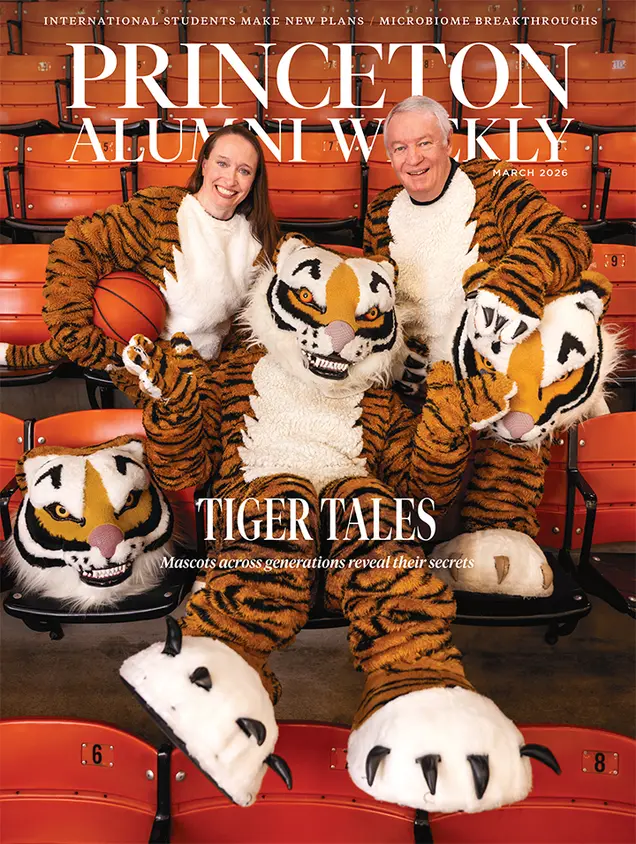

Paw in print

March 2026

Mascots across generations; biome breakthroughs; international students make new plans.

No responses yet