As an undergrad, Bill Farrell ’77 was proud to coach Princeton’s fledgling women’s track and field squad. Decades later, he found similar joy helping classmates to distribute much-needed wheelchairs in South America.

PAW podcasts are also available on iTunes — click here to subscribe

TRANSCRIPT

Brett Tomlinson: This month on PAW Tracks, we hear from Bill Farrell ’77. As an undergrad, he was proud to coach Princeton’s fledgling women’s track and field squad. Decades later, he found similar joy in a Class of ’77 service project. We begin with the track story, which started in his junior year.

Bill Farrell: I was on the men’s track team, a very short career as a runner, and then Larry Ellis said, “Why don’t you be my manager instead?” And I was manager at the end of my sophomore year. And I was working my way through college too. So I would say the stress of working 35 hours a week, doing track, studying, I took a year off to make some money, came back, and thought I would be able to run the men’s team. Instead Roy Chernock, who was then the assistant track coach, and Sam Howell, who was the assistant AD pulled me aside and they said hey Bill, we have a special project just for you and we think you’d be really good at it.

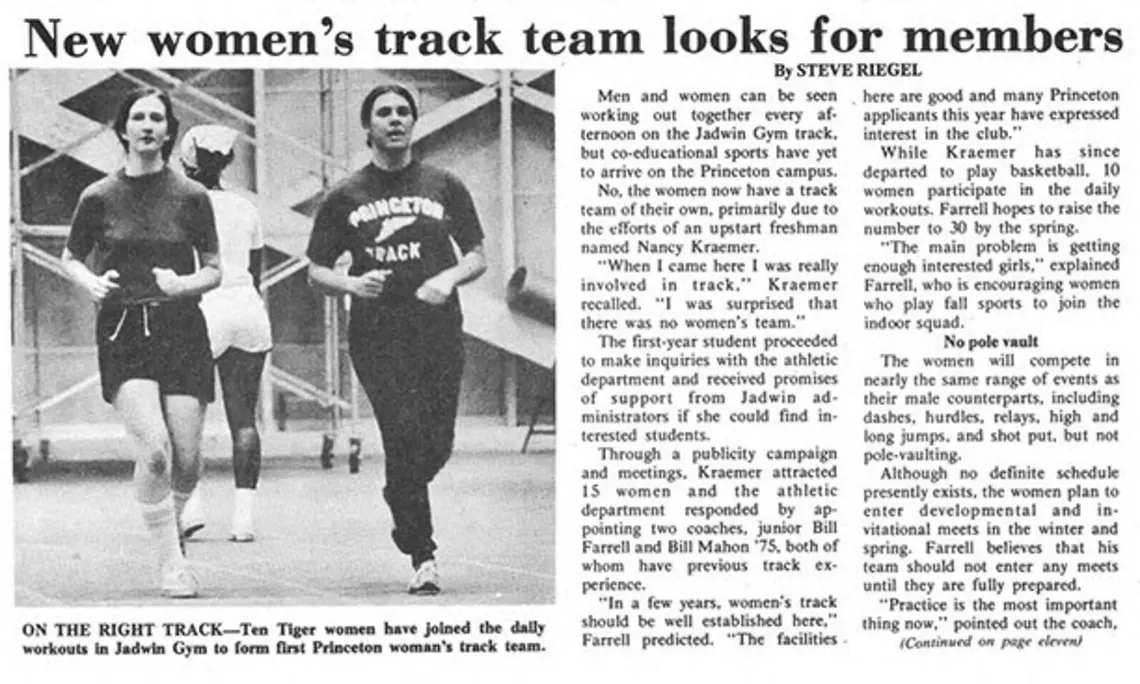

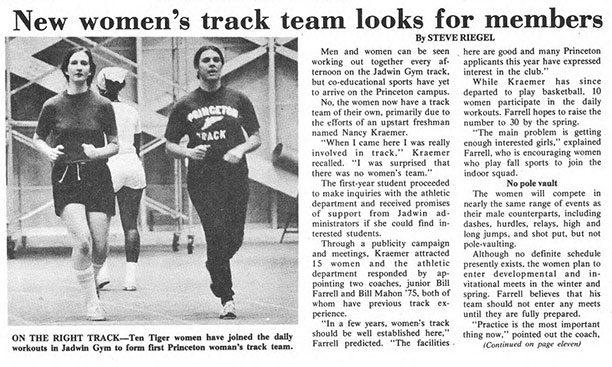

And so basically, the previous assistant men’s coach, Richie Robinson, had promised a number of women that if they came to Princeton there would be a track team for them to run on. Rich left the University, and this was a surprise to Larry Ellis, to Royce Flippin, the athletic director. And so, they referred it down one level to the assistant coach and the assistant athletic director, and they approached me and they said, you know, we’ve got a bunch of women — one of them was very good in high school — and we’ll pay you an honorarium of $500 for the year if you coach the first women’s track team. And it was really that one woman was a woman named Nancy Kraemer, Class of ’79, Nancy Kraemer-Crocker now. And she was the New York state discus champ. She also was a very good high jumper, javelin thrower, quarter miler, and then the following fall she was a very good cross-country runner. So a great natural athlete.

And so next fall, the fall of ’76, the team really got started in earnest. Nancy went around putting posters on trees freshman week. I went around to all of the women’s sports coaches saying if there’s a good natural athlete that just doesn’t make your team, we have a women’s track team, or if there’s an athlete’s that you have on your team and you want her to stay in shape have her out on the track team when she’s not doing tennis, or lacrosse, or whatever, because track is a three-season sport.

And so, we had some pretty good athletes come together. We had our first cross-country season. We had the course — it was a two-and-a-half-mile course, it was totally on campus, and that got people to come down. It was down part of campus that’s no longer fields, but Poe Field and go down Elm Drive. And we also had some people that were just natural athletes. There was a girl, Liz Levy, who grew up on the east side of Manhattan, a couple blocks from Central Park, and that was before the running boom, before people actually ran or jogged, but she was an early pioneer in that. She was a very good runner. So we had a good cross-country team.

And then we were joined by a freshman, Jill Pilgrim, who was from New York City. She was a member of the Atoms Track Club, which was one of the two or three really good women’s track clubs in the United States at the time. And she was a good 200-meter, 220 runner.

Among the walk-ins or walk-ons, I remember a girl came down and she said, “I’d like to run. I’m a rower and I don’t like rowing in the tanks and this is my way of staying in shape.” I said, “Well, OK, we have a meet tomorrow, but next week we’ll start you working out and maybe the next meet you can run.” And she goes no, I want to run tomorrow. So she comes down and she ran the mile and she almost won it. She ran about five minutes flat and I said you know you should skip rowing and take up running. And she didn’t quit rowing, and it was a good thing because she was an Olympic medalist in rowing. But those are the kinds of people that we were getting to come down, and they might run a few races. But by the end of that spring, we had one of the better teams.

Princeton, the athletic department, I think were surprised by the success we were having, and it kind of forced them to go out and hire a real coach. I think they originally were going to say well, let’s have, you know, a student from the track team or with a track background do this for another couple of years when Bill graduates.

And so, they did a search and they hired a great coach, somebody with the same last name as me, Peter Farrell. We have no blood in common, but Peter went to the same high school I did. And he was, I think seven years ahead of me and he was a national record holder, national champ. The timing allowed him to come along. When he retired last year, and they threw a dinner, I mean I was near tears because he said look, if it weren’t for you, in front of everybody, if it weren’t for you and what you did this team would not have been the same. And, you know, I’m not sure if that’s true, but there were people who said, you know, I always knew you had something to do with it, but when Peter gave that talk about what you did, now I understand.

BT: Two decades later, Farrell would join a team of a different sort, working with classmates to bring wheelchairs to people in need in Guatemala. The project was a collaboration with the Wheelchair Foundation, a charity founded by the father of classmate Dave Behring ’77. What started as a one-time trip turned into a long-term mission. After its visits to Guatemala, the class moved on to Peru. Farrell has been part of the group of classmates that travels to deliver the wheelchairs, in person.

BF: Five years ago, we took, distributed wheelchairs from sea level to over three miles high making various stops. And again, you go into these small towns or small cities and in one case, we had a famous -– the equivalent of a local rock star. We had the army all there. Everywhere we would go, we were, you know, we went into this tiny little town Tarma. They played the U.S. national anthem, they raised the stars and stripes, they, I mean they did the Peruvian national anthem, and, you know, there were tears coming from our eyes. This is, you know — we were given medals, but the nicest thing is and it — I remember saying to somebody, you know, you always hear it’s better to give, or you get more joy out of giving than receiving. And if you have young kids you see that, you know, Christmas Day or so, but it was the same thing for the classmates that we brought along to see that it, you know, was so wonderful to give and to help people.

So, we’ll see how long we can keep on doing this. I’d really like to enlist a younger class that we can hand this off to, and I know a lot of classes do great things for their reunion projects. We think ours is really special.

BT: This interview was recorded at Reunions in June; in August Farrell and his classmates returned to Peru to deliver a new shipment of wheelchairs.

Our thanks to Bill Farrell for sharing his story. Brett Tomlinson produced this episode. The music is licensed from FirstCom Music.

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet