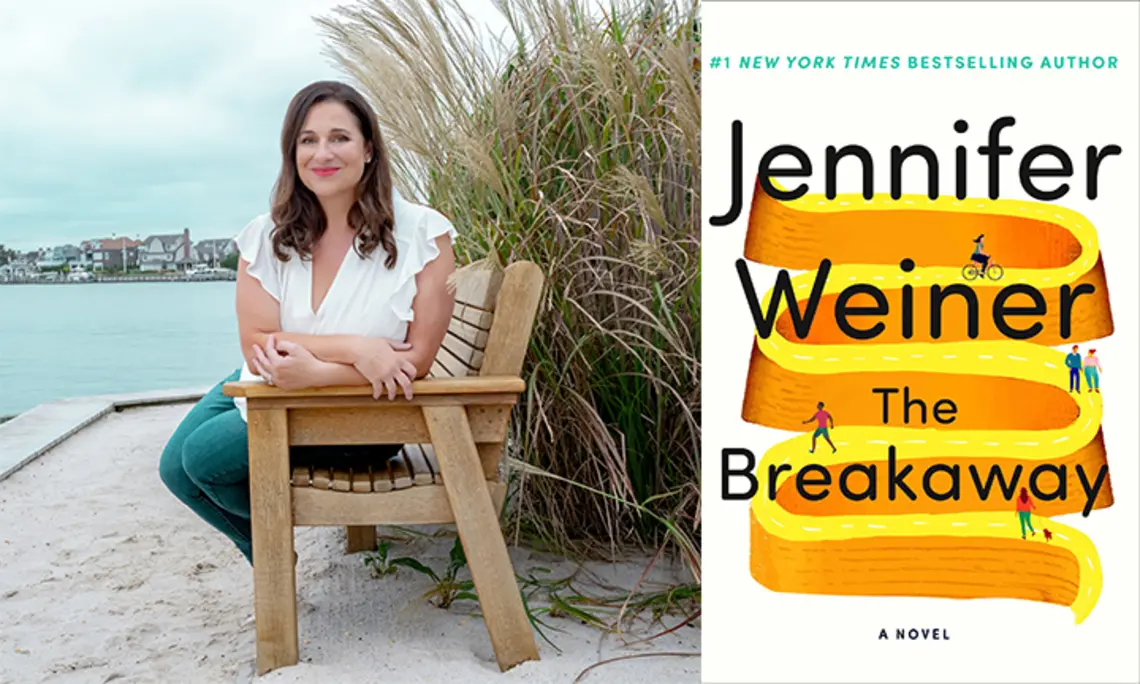

PAW Book Club: ‘The Breakaway’ by Jennifer Weiner ’91

“Abortion is a topic that gets very polarized very, very quickly. And I think that one of the things that fiction can do is give us a level of remove... . We’re playing in the neighborhood of make believe.”

Welcome to the first podcast from PAW’s new Book Club, where Princeton alumni read a book together and send PAW their questions for the author. We received some terrific questions for our very first author, Jennifer Weiner ’91, about her latest novel, The Breakaway.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

PAW Book Club is proud to be sponsored by the Princeton University Store. Missed this read? Join us for the next one, Michael Lewis ’82’s latest book, Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon. Sign up online here, and consider buying your book from the U-Store online here.

TRANSCRIPTION:

Liz Daugherty: Hello, I’m Liz Daugherty, digital editor of the Princeton Alumni Weekly. With this podcast, I am very pleased to launch the new PAW Book Club, where Princeton alumni read a book together and send us their questions for the author. We’re proud to be supported by the Princeton University Store — that’s the U-Store to alumni — as the book club’s official sponsor. 326 readers have signed up so far, and we received some terrific questions for our very first author, Jennifer Weiner, Class of ’91, about her latest novel, The Breakaway.

Jennifer is a prolific writer and frequent topper of bestseller lists whose well loved novels include In Her Shoes, which was made into a movie starring Cameron Diaz, Tony Collette, and Shirley McLean. The Breakaway hit shelves this summer, and it impressed us at PAW by pulling readers breezily into a story about a bicycling trip led by protagonist Abby Stern, and then layering in thought-provoking and, frankly, controversial themes.

Jennifer, thank you so much for being with me today.

Jennifer Weiner ’91: Absolutely.

LD: I’d like to start with this question from Juliette Reynolds ’86, because she did a fantastic job summing up some of the interesting themes in The Breakaway, which might be helpful here for any listeners who haven’t read the book, although I’d really recommend reading the book. So here goes.

Juliet writes, “Your book incorporates so many strong themes from the many issues surrounding body weight, such as the stigmas associated with obesity, the incredible need for body positivity, and the pitfalls of using BMI as an indicator of health, to other areas such as a woman’s right to reproductive health care, the hookup culture, the horrible impact that social media can have on an individual, an exploration of mother-daughter relationships, and so much more. My question is, in The Breakaway, which came first, which theme made you want to write the book? Or if all these themes were swirling in your subconscious, at what point did you decide to string them together into a book?”

JW: Wow. That is a great, great question. And it’s kind of a classic question for an author. It’s like which came first, the chicken or the egg; which came first, the characters or the story that you’re telling about them? And I wish that I had a really snappy answer, like I knew that I wanted to write about bodies or reproductive rights, or mothers and daughters. But the truth is, all of it was swirling, right?

So I am a middle-aged woman, a middle-aged white Jewish woman who has lived her whole adult life in a larger body. I am the mother of two daughters. I am an avid cyclist. I am someone who lives in the world and pays attention to the news. And obviously when Roe vs. Wade was struck down, as the mother of daughters, as somebody who had to sort of manage her own reproductive life for many, many years and is now sort of launching young women into a world where unbelievably they have fewer rights than I did — all of that was in my head when I set out to write The Breakaway. And I guess the first piece of it that I had was the idea that I wanted to write about a bike trip. That was the piece of it that came first. And once you know that you’re sending your character on a journey, then you can start thinking about like, OK, well where is she starting? Where is she going? What are the obstacles she’s going to encounter?

LD: So one of the main plot lines in The Breakaway involves a teenager seeking an abortion, as you just mentioned, and we actually have a great question from an alum, Dave Setter ’82, who sent an audio file, which for future podcasts, this is great because we’re going be able to include his audio in the podcast.

Dave Seter ’82: Hi, my name is Dave Setter, Class of ’82. The Breakaway deals with the issue of abortion in a thoughtful and thought provoking manner, exploring the mixed emotions of the character Morgan, who does not take her decision lightly. Given the polarization of our nation on the topic of abortion, and therefore, the difficulty of engaging in conversation with persons holding opposing points of view, do works of fiction have a role to play in this conversation? In other words, does exploring the topic through a fictional character make it easier to have the conversation? Thank you.

JW: That is a really, really great question, and I think the answer is absolutely yes, as someone who believes in the power of fiction, the power of novels, the power of stories to do two things. They can function as mirrors, where you look into them and you see your own values, your own beliefs, your own ideas reflected back at you. Or they can be windows where instead of seeing yourself and what you think, you are seeing into someone else’s thoughts or feelings or histories or belief. So, I know that there are people, a lot of people, who read The Breakaway, who read any of my books or my op-eds or my social media or whatever, who believe what I believe, who grew up have similar backgrounds to what I’ve got, who were educated in similar places, and who are completely aligned with what I feel about this issue. And I know that there are people who feel very, very differently.

So how do you have that conversation? Because abortion is a topic that gets very polarized very, very quickly. And I think that one of the things that fiction can do is give us a level of remove where it’s not like I’m telling you about my daughter or my friend’s daughter, or this is what happened to me when I was 16. We’re playing in the neighborhood of make believe. Right? These are invented people who are dealing with real problems, but the fact that they’re not anyone you’re going meet on the street or at a party or a PTA meeting, I think does make it easier for you to kind of play with the what ifs.

And I hope that people who read The Breakaway who do not believe that a woman should have the right to choose and control her own reproductive choices and decide whether to continue with a pregnancy or not — maybe this book isn’t going to change their minds, but I hope it’s going to give them some insight into how people, how young women who are making these choices are having to make them in a world that is giving them fewer and fewer options, fewer and fewer roads they can take, places they can go for help. Again, Morgan isn’t a real person, but I do think her dilemma is very, very real. And I hope that people who read her, they’re either going to sympathize or maybe just have their eyes opened a little bit and consider more the idea that like every law that we change, every time that we tell a woman that she doesn’t have this option and she doesn’t have that option, there are very real human consequences to those decisions.

LD: We have another question that’s kind of along the same lines, about that thread of abortion, which obviously was a really powerful and big part of this book, it’s no surprise. So Nancy Herkness Theodorou ’79 — I hope I’m pronouncing that right — says, “I admire your courage in taking on the issue of abortion access. As a writer of commercial fiction, do you worry that you will lose readers as a result of addressing such a controversial topic? Have you heard from any readers who are upset by this topic?”

JW: So yes. I think anytime you wade into anything that is in any way controversial, you have to be ready for the possibility that you’re going to lose readers. And yes, I hear from those readers. I hear from readers who don’t like the stances that my characters take. I hear from readers who think that there are too many curse words in the book. Everybody’s got something to say. And, I guess there’s two ways to look at this.

There’s the Michael Jordan way of looking at it. Way back in the day, Michael Jordan was asked to endorse a senatorial candidate. Jesse Helms was running for Senate, and Jesse Helms of course was a rabid segregationist and a bad, bad guy. And there was a more progressive candidate who was running, and people really wanted Michael Jordan to endorse that guy. And Michael Jordan didn’t. And when they asked him why, he said, Republicans buy sneakers too. And he was selling Air Jordans, and he was like, look, I don’t want to alienate all of those potential Air Jordan shoppers by coming out against Jesse Helms.

So yeah, I mean, there is a school of thought where it’s like, you don’t rock the boat. You don’t upset a possible book buying constituency. You just sort of play it right down the middle. I guess I, oh God, this is going to sound wildly pretentious, but I do sometimes think about my legacy and like, what is the power that I have as a commercial bestselling author? Who can I speak to? Who can I possibly convince to maybe think a little differently or to be a little more open-minded? What is my job here? What am I supposed to be doing with this power that I have?

And as a woman who believes ardently in reproductive rights, as the mother of, I have a 20-year-old daughter and a 16-year-old daughter and would like very much for them to have agency and control over their own bodies, their own sexuality, their own reproductive decisions, it really didn’t feel like much of a choice whether to go there or not. And I had conversations with my agent, and I had conversations with my editor, and we talked about what was going to happen and how to answer questions when I went on book tour. And you know, what to do if I was confronted by someone who was angry or who felt betrayed, or, you know, “This isn’t what I picked up a beach read to get into.” But I do think that commercial fiction can function wonderfully as a Trojan horse sometimes, where people don’t necessarily think — they’re picking up something that looks light and fun and frothy and getting a novel of ideas or a novel that sort of takes on political questions. So you can kind of sneak up on ’em that way. And I think that is something I’ve been proud to be able to do, possibly in spite of losing some readers or alienating some people along the way.

LD: I have to ask a follow-up question. Have you been accosted by anyone at a book reading or an author event? Has that happened to you?

JW: That hasn’t happened with this book. I mean, they email or they post stuff on Amazon, which I don’t look at, or Goodreads, which again, I don’t look at. I think those are places for readers to talk to each other and it’s sort of none of my business as an author what anyone has to say in those places. So, no, like nobody has has shown up at a reading to scream at me. But the paperback tour hasn’t happened yet, so it’s early days, guys.

LD: I think that’s so interesting. When you’re talking about fiction, particularly women’s fiction, which I think is something that you’ve spoken about quite a bit — I think if the personal is political, right, this is where you can really get into people’s heads. And make people understand what’s going on. And this particular situation with Roe feels like such a need for that, for people to understand what happens within a person in a situation like this.

JW: The personal is political is, is so true. And I think anytime you’re writing about women, you’re writing political books, whether you mean to be doing it or not. You are.

LD: Now, Nancy also asked a follow-up question, which I think is a lot easier, I think. So here we go. Nancy also wanted to know: “If you’ve gone on a cycling trip,” I think you have, “which character were you?”

JW: OK, so I have gone on some biking trips in my day. I have never led one, so I’m not exactly sure who I’d be on this trip. I’ve never taken my kids on one. Honestly, I would probably just be like somebody whose name doesn’t even get mentioned, who’s just in the back sort of pedaling along and like quietly taking notes or something like that. But bike trips are great because I think on a bike trip, sort of like any other kind of travel, like a cruise or like a group tour, there’s a level of almost instant intimacy with these people. They’re strangers one day, and then after a day of riding together and sharing meals, by the next day you are telling each other like things you haven’t told your therapist after 10 years of therapy. You’re going to be very close to them for a set period of time, and then maybe you’re never going to see them again. And I think that there’s something really special that happens on those occasions. So, yeah. I highly recommend bike trips, I think they’re lots of fun.

LD: So similar, from Carla Lewandowski ’04 — here we go, we’re gonna launch the film right now — “Which actor or other well-known person did you picture when you thought of Abby?”

JW: Oh, wow. OK. So I am the least visual thinker you would probably ever meet in your life. I am so, so bad at this. When I wrote my first book, which was called Good in Bed, much to my mother’s dismay, I remember my publisher asking, do you have any ideas for the cover? And I’m like, I have the greatest idea for the cover. I’m like, are you ready? Are you sitting down? Are you ready? Are you sure you’re ready? I said, OK, so on the front cover, it should be a bed, but the bed is made and it’s neatly made, and the pillows are plumped. And then when you turn the book over, it’s the same bed, but the bed is not made anymore. The bed is messy. Like someone has slept in the bed. And I wait for the, I hold for applause. No one applauds. They just look at me and they’re like, OK, thanks. Yeah. And they never asked me again, over the next 15 novels, I was never asked again if I had ideas for the cover.

I am a crappy, crappy visual thinker. And I don’t tend to picture people in my head. I always know how they sound. I can hear their voices, but I really do not have an easy time picturing their faces. And that is especially true when I am writing a plus-size female character because who are the plus-size actresses in Hollywood right now? I cannot think of more than like two or three. So I really was not imagining anyone, looks-wise. And in terms of, if you ask me right now, who should play Abby, I don’t even think I have a good answer for you. Except I do! I do, Bonnie Milligan, who is on Broadway, and she won the Tony for her part in Kimberly Akimbo. And she is larger and she is the most amazing, incredible singer and actor, and she’s the right age to play Abby. So Bonnie Milligan, if you’re listening to this, or if anybody knows Bonnie Milligan, she’d be a fabulous Abby. I think she’d be great.

LD: Oh, that’s awesome. All right, cool. So from Charles Riley ’79, this sounded like a question from a writer, so maybe Charles is a writer. He said: “How do you sustain your writing without lapsing into cliche?” And he notes, this was nice, he notes your “elegant metaphor of riding the bicycle that attests to your stylistic prowess.”

JW: That is very kind. OK. So I, I think the answer is, I, I was an English major in college, lo these many years ago, I was lucky enough to study creative writing with Toni Morrison and Joyce Carol Oates, and I studied nonfiction with John McPhee (’53), and I think that it was John McPhee who probably had more influence than anyone over my writing in terms of looking at a first draft as a starting place. You don’t sort of wait for your muse to whisper in your ear and then you just transcribe what the muse has told you, and then it’s done and it’s perfect and nobody needs to touch a word of it. You write your first draft and then you rewrite it, and then you rewrite it, and you rewrite it, and you look it again, and you rewrite it some more. And then your agent reads it and gives you notes and you rewrite, and then your editor reads it and gives you notes and you rewrite.

And I, with every book, I hope I’ve gotten a little bit better at doing this. I really do a read where it’s just for cliches where it’s like, OK, is there a fresher way of saying this? Is there a less familiar way of saying this? Am I using tired language, something that we’ve all heard a million times already? And again, I’m not sure that people necessarily are coming to commercial fiction for beautiful sentences. I think that they go to prize-winning literary novels for that. But that doesn’t mean I don’t think it’s part of my job to sort of say things in fresh and new and vivid ways. And I really do pay attention to the words.

LD: All right. Now we have from Susan Rhoades *92, she says: “You often feature mother-daughter relationships in your novels. This one showcases several, including some surprises from their past revealed by two mothers to their daughters.” I’ll note here that the protagonist, Abby Stern discovers her mother had major struggles with her weight, but never knew her mother actually had bariatric surgeries; part of what you need to understand for this. “Have you had a similar revelation-type moment in your own family, either as a mother or a daughter?”

JW: I think that when we’re kids, when I was a kid, it’s like you don’t even think of your parents as people necessarily. They’re just your parents. And you are the main character and they are supporting characters and their job is to assist you or antagonize you or push you forward or hold you back. But they’re not really their own people. And then you become an adult and you start to realize, oh wait, they’re the main characters in their own lives. And they had parents too, and they had struggles and they had people who held them back and people who pushed them forward. So yes, in this story you’ve got two young women, one who’s a teenager, Morgan, who’s 16, and then Abby, who’s in her early thirties, who both have sort of told themselves a story about their mom and who she is and what she believes and how she sees them or how she’s going to see them.

In Morgan’s case, Morgan is terrified that when her mom learns that she is sexually active and that she’s gotten pregnant, her mom, who is very devout, very religious, married to a pastor, is going to hate her, is going to be just profoundly, profoundly disappointed in her. And Abby — who is doing her best to sort of live happily in a larger body and has one of these “almond moms,” one of these like counting out eight almonds for her afternoon snack and weighing her chicken breasts and sort of paying attention to every mouthful of food that she consumes — Abby sort of assumes that she’s a disappointment to this woman and that her mom has disappointed her in her values and her beliefs. So there wasn’t anything that happened in my own life with my own —

Oh, no, wait. As I’m saying that, I’m realizing that’s not true. This is funny. I sort of forgot all about this. When I was in my twenties, my mom came out, my mom announced that she had fallen in love with a woman. This was like 10 years after she and my dad had split up. And I remember being on the phone with my siblings, I’m the oldest of four, and I was like, did you see anything? And my brothers are like, no. And my sister’s like, did you see anything? And I was like, no. And then we were like, well, well, she always had short hair and she never wore makeup and she always wore like L.L. Bean parkas. And I’m like, we lived in New England! That was every woman, that was everyone’s mom. How was I supposed to know? And I think the truth was that maybe thinking about your mom as like a sexual being is just a difficult, difficult thing.

But I think it was the idea that she was mom, that was her identity. And how dare she like break out of this role that we’d assigned her? So I do think that parents, that moms specifically have within them the capability to surprise their children, to flip the script, to change the narrative, to say in their forties or fifties or sixties or seventies, you know, I am the main character here or I am a main character just as you are. Boy I wonder how my daughters would answer this if somebody’s like, did your mom ever do anything that you didn’t see? Oh boy.

LD: It’s probably inevitable. If the day hasn’t come, it probably will someday, for all of us.

JW: Right? They can work it out in therapy.

LD: So Stephanie Kim ’94 asked about the part where Abby’s mom confesses to her about her own weight issues and the bariatric surgery. She writes, “Could words of advice to daughters growing up to be, think about what your mom feels and is advocating for and why? There might be specific experiences she underwent that explain why she parents as she does.”

JW: Yes, that is very profound and that’s very true. And I wonder how many daughters have the possibility of doing that. I mean, I’m imagining every movie scene, every television [scene], where it’s a daughter slamming a bedroom door and yelling, “You just don’t understand!” Maybe it’s the daughters who aren’t making enough of an effort to understand how their mothers grew up, what the pressures they were under had been. Just seeing our moms as people, I think is a big lesson. I think it’s a lesson for the women, the young women in The Breakaway. I think it’s maybe a lesson for lots of women in the world that your moms are people, were people, had their own stories before you ever came along and will continue to have their own stories once you are out of their house and living your own life.

So yeah, I do, I think that if any daughter who reads this book is able to look at her mom with a little more sympathy and a little more understanding and a little more nuance, I think that’s a really good thing.

LD: There’s probably a lesson in there for those of us who are mothers as well, to let ourselves be seen as people. Beause I think — you probably feel this, too — you want to model the best for your kid and you want them to look up to you and see you as flawless. And in the long run, that’s probably not what’s best for them, because that definitely happened here.

JW: Yeah, and it’s something I think about a lot with body stuff, which there’s a lot of body stuff in The Breakaway. There’s the pressures to be thin, the pressures to sort of force the world to accept you just as you are, the idea of being physically active and at what size are you allowed to do that and how do people see you in the world? And do people assume that any larger woman who’s active is just trying to make herself smaller?

But I think about the advice that women get, which is like, don’t let your daughters see you dieting or obsessing about your body or criticizing your body or saying things like, “oh, I was so naughty last night,” or “I have to get on the treadmill to burn off that chocolate cake that I had, and I shouldn’t have done that.” We’re supposed to ideally not even think it, but definitely not to speak on it, not to talk about our bodies in that way where our daughters can hear us. And I wonder if maybe there’s like a step in there where it’s like, try to love yourself, try to accept yourself, try to be comfortable just as you are so that your daughter can be comfortable in her body just as it is.

But maybe it’s like just saying to your daughters, I’m trying to unlearn decades of toxic thinking. And sometimes I hear these voices in my head that tell me I should give intermittent fasting a try, or I should go get on that treadmill right now, or whatever it is, and just say: Here’s where I think those voices come from, and maybe it’s your own mother and maybe it’s capitalism and maybe it’s the weight loss industry, or whatever it is. And just being honest: Here’s what I’m struggling with, and here’s what I grew up feeling, and here’s why I don’t want you growing up feeling that. But boy, coming clean can be a hard, hard thing, you know? And maybe it’s easier to do in fiction than it is in real life.

LD: That’s probably very, very true. But I think you’re onto something there, letting your kids see the struggle, because they’re going to go through it whether you want them to or not.

JW: Right. And the idea that we are all out here just like unassailable and perfectly comfortable and perfectly at home in our own skins. I mean, boy, kids can sniff out dishonesty. They’re like bloodhounds. They know, they know.

LD: That’s so true. All I have one more question, and this is from Susan Rhoades again, and I just thought that this sounded like a great question to wrap it up here on. OK. So she writes: “I appreciated how you ended this novel with the main character feeling more independent and confident in herself, and excited to start a new romantic relationship, but also not defining herself by it. Is it hard to convince editors to leave a novel more open-ended rather than a happily ever after?”

JW: That’s a great question, and I can tell you, I wrote the ending of this book over and over and over because I felt a lot of internal pressure to give Abby the kind of stereotypical happily ever after, or happily for now ending that still, in the year of Taylor Swift and Beyonce 2024, still involves a guy. Or a girl. But a romance, right? Like that is what happiness looks like. It’s not you finding your career path. It’s not a friendship, it’s not a job, it’s not a great apartment, it’s not a life that you want, or it is all of those things but there also had better be somebody to kiss you and call you sweetheart at the end of the day.

And to their credit, my agent and my editor, all of those people seemed very, very willing to have Abby sort of choosing that third path where it wasn’t the guy she started off with, and it wasn’t the guy who she reconnected with, although one of those guys sort of stayed in the picture and one of them did not.

But Abby chose herself, more than a romance at the end of the book. She chose herself and she chose the idea of paying forward what she learned to other young girls, by teaching them how to ride a bike. And by helping them get to the point where they could ride their bike for 10 miles, 20 miles, 30 miles, knowing that that was a gift she was giving them, that sense of independence and freedom and power, and that no one would be able to take that away.

I like love stories, I like happy endings, I like books that end in wedding bells. I love those stories. I love romantic comedies, I love watching those movies. But I think that there’s something also very satisfying about the idea of a woman who chooses herself and in doing so, understands that you have to really have chosen yourself before you’re ready to meet somebody else on that playing field.

LD: I love that. Well, that actually goes through all the questions that I had prepared from our wonderful book club members. I always say this at the end of podcasts that I do, but is there anything else that you would want to talk about or mention?

JW: This was so fantastic, these were great questions. Boy, I usually get a whole lot of like, how did you find your agent? And like, can you tell me how to write a book? Do you use a pen or do you write on a laptop? So it’s very, very nice to get questions about themes and language and messages and all of that stuff. So I am just so grateful for this conversation.

LD: Well, thank you so much for taking the time and being a part of this. We really appreciate it.

JW: This was great. Thank you.

The PAW Book Club podcast is produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly, and anyone can sign up through our website, paw.princeton.edu. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode, also at paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet