PAW Reunions Panel: How the News Media Covers the MAGA Movement

‘The press is doing its job, but Congress, there’s no sign of vertebrate life up there. If Congress and the other institutions in our democracy aren’t responding to those stories, then it is like the tree falling in the forest’

How is the news media covering the MAGA movement? Four journalists and a Princeton historian at the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s 2025 Reunions panel delved into questions about reporting on Trump voters, whether the press should use the word “lie,” today’s fragmented media landscape, and how even the most explosive investigations don’t spur change the way they used to. For this episode of the PAWcast, we’re pleased to share a recording of the session.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT

This is the Princeton Alumni Weekly’s PAWcast, where we talk with Princetonians about what’s happening on campus and beyond. For this episode, we’re pleased to bring you a recording of PAW’s 2025 Reunions panel, titled “How the News Media Covers the MAGA Movement.”

Mark Bernstein: Good morning, everybody. I think we should get ourselves started. Thank you for coming to the panel this morning. I’m Mark Bernstein. I’m the senior writer for the PAW, and we have our very distinguished panel here. Before we start, there’s some boilerplate that I’m supposed to read, which I just lost off my phone, but I think we can summarize it. You all know the rules that this is, everybody is speaking in their own private personal capacity. It’s not representative of the University or PAW.

The University encourages everybody’s right to express themselves as they wish, and we’ll have time for questions at the end. By the way, can everybody hear me all right? Am I speaking well enough into the mic? That if there are interruptions, people that try to shout anybody down, or don’t allow the discussion to go on, that we’ll have to intervene. If necessary, if you won’t behave, you’ll be asked to leave. With that, let me briefly introduce our panel. I’ll go down the line here.

Marc Fisher, Class of ’80, is a columnist and associate editor at The Washington Post, where he has worked for 39 years as a reporter, editor, correspondent, and columnist. He is a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and the author of several books, including Trump Revealed, a bestselling biography of Donald Trump, which fits him very well for this panel; Something in the Air, a history of top-40 radio that examines how old media adapt when new technologies burst into the marketplace; and After the Wall, which traces the experience of five East German families as the Berlin Wall falls and communist East Germany disappears into the West. Marc has taught creative nonfiction as the Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton, and has also taught at an American University and George Washington University.

Next down the line, Kathy Kiely, Class of ’77, is the Lee Hills Chair in Free Press Studies at the Missouri School of Journalism. She says she self-deported from Washington D.C. in 2018 after working for nearly four decades as a reporter and editor covering Congress, the White House, and 10 presidential campaigns. She is an emerita trustee of The Daily Princetonian, and next week, she is wrapping up a four-year term as a University trustee.

After that, we have Peter Elkind, I’m sorry, I’m just moving around, also Class of ’80. We have two members of the great Class of 1980 here — give a shout-out. Peter is a national reporter at ProPublica. Peter’s focus at ProPublica is now on the Trump administration and business. Before joining ProPublica in 2017, he worked at Fortune for 20 years as a writer at Texas Monthly, and edited The Dallas Observer.

Peter is the co-author of the bestseller, The Smartest Guys in the Room: The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron. He also wrote Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer, ’81, and ’81 was not part of the title, and The Death Shift: Nurse Janine Jones and the Texas Baby Murders. He’s written about FBI director James Comey’s mishandling of the Hillary Clinton investigation, profiled Donald Trump’s accountants, investigated how America’s biggest oxygen company repeatedly cheated Medicare and elderly patients, and revealed how Steve Jobs concealed his fatal battle with pancreatic cancer. His work appeared in the New York Times Magazine, New Yorker, and Washington Post.

Finally, we have who I think many of you are familiar with, Julian Zelizer, who is a New York Times bestselling author. He is the Malcolm Stevenson Forbes Class of 1941 Professor of History and Public Affairs at Princeton, a columnist for Foreign Policy, and he publishes a Substack newsletter, which you should all subscribe to, called The Long View. He’s a regular guest on NPR’s “Here and Now” and a popular analyst on multiple television and radio networks.

I’m sure you’ve all seen him doing that. He’s the award-winning author of 27 books, and editor, including The Fierce Urgency of Now: Lyndon Johnson, Congress and the Battle of the Great Society, the winner of the D.B. Hardeman Prize for best book on Congress, and Fault Lines: The History of the United States Since 1974, which he co-authored with Princeton professor Kevin Kruse.

Why don’t we get underway, and I’ll start off and we’ll ask our panelists to go through and discuss this, but the topic of our conversation today is how the news media is covering the MAGA movement. Let me ask you, how do you think the news media is covering the MAGA movement, and how, if at all, has that changed for better or for worse since the first Trump administration? Marc, you want to...

Marc Fisher: OK. How has it done that? It has done, the news media have covered Trump this time around brilliantly, appallingly, not at all, a whole lot — because I have no idea what anyone means when they say the news media. None of us should have any idea, because the media landscape in this society has become so splintered that there’s no such thing as the news media.

For example, the podcasts of Joe Rogan, Tucker Carlson, and Candace Owens, which are all forums for Holocaust deniers, anti-vaxxers, the whole works, Qanon, and so on, they have tripled the audience of the New York Times, Washington Post, Atlantic, and New Yorker combined. So which is the news media? Fewer than 20% of Americans pay for what we would think of as traditional legitimate news sources. Fewer than a quarter of Americans regularly read anything that would pass for old school news media.

Whether you call folks like us in the old newspapers and TV networks and so on, dinosaurs or just the rotting carcass of an industry that won’t exist shortly down the line, we’re not the news media. We have, as we all know, we live in these silos. In those silos, you have your own set of facts and your own view onto the world. Having lost that foundation that had really only existed for a few decades of limited choices and news organizations that, in order to make money, had to be fairly responsible, that business model is gone.

That business model having collapsed because of the demise of department stores, the rise of Craigslist, the old business model that supported most news organizations simply doesn’t exist anymore, and no one has found a good substitute. As a result, we each choose our own information environment. In that context, we cover Donald Trump the way our organization’s background leads us to.

At my paper, we’ve, I think, broken more stories about Donald Trump this time around than probably the first term. A lot of good, tough, investigative work, a lot of daily coverage, but our audience is maybe a quarter of what it was during his first term. You can find great work being done, but you do have to look for it.

Kathy Kiely: OK. I’m a little less gloomy, mainly because—

Marc Fisher: I can go much gloomier.

Kathy Kiely: Right. I know you can, Marc, but I teach journalism, and I’m really happy to say, and I’m really happy to see those two young ladies with the tiger ears over there, because that’s really what this is all about. It’s about the future. All of the problems that Marc outlined are real, but part of the answer, and it’s not going to be a quick answer. There is an app you can use. It requires no electricity, and everyone has it between their ears.

But it does require critical thinking, and I think events like this are actually very important, because I think part of the way out of this Tower of Babel where, as Marc has well described, this is a very Balkanized audience environment, part of this the way out is education, public education. We really need to help people understand that there is a difference between fact-based reported news provided to you by people who care enough about their reputations and your reputations, that we correct mistakes when we make them.

There’s a difference between that and algorithmic mind control and propaganda. Helping people to understand that, and I think certainly at a place like Princeton, where this is the place that educated the guy who wrote the First Amendment, there’s no better place for that kind of work to happen.

And I will just say that as somebody who was a member of the Washington press corps, I’m very sympathetic with the dilemma that Trump represents, because we have always operated as journalists under a certain set of norms. But those norms depended on our sources operating by a certain set of norms, one of which was not outright lying 24/7. If you maintain your journalistic norms in the face of that, it seems to be enabling. I think we’re all struggling as journalists to figure out a way around that, while maintaining the professionalism, the credibility, and yes, the neutrality, that allows us to give a full picture.

I will say, as somebody who comes from the industrial Midwest, that the MAGA movement started long before Donald Trump, and maybe what we should be doing is looking at the origins of the MAGA movement, not at the guy who is trying to lead it.

Peter Elkind: I hope you heard most of, if not all, of what both Marc and Kathy had to say, because their characterization of the changes and the scenario and the environment that we’re operating in, I think, are spot on. The media has grown incredibly more diverse and complex. The audience has changed. I’d like to talk a little bit about another piece of the story.

I’m at ProPublica, and the purpose of ProPublica’s sort of central mission is to do accountability stories, and we’ll do investigative reporting, it reveals important things, and ideally prompts a response and change and correction of bad behavior and issues that should be addressed. On that front, there’s been a very dramatic change. It’s not just that the administration is offering a flood of falsehoods and denying things, won’t respond to inquiries to the press, but also the response to revelatory stories is quite different than it used to be.

Think of what used to amount to a scandal a few years ago, and how dramatically it would destroy a career, alter the trajectory of a policy approach, just change the landscape. Lots of very important, shocking stories of all sorts are published by The Washington Post, by ProPublica, by The New York Times, massive revelations that would be enormous scandals, and as I said, change the landscape. They prompt a pretty underwhelming reaction.

Part of that is because the government apparatus to deal with revelation and scandal has been in good part neutered or dismantled, or is in the process of being neutered or dismantled. The Justice Department doesn’t respond the way it did. Inspector generals are gone, various regulatory agencies have been stripped down. That’s a reality that we can talk about. There’s a lot of very good work being done, and there’s an awful lot to be done, but the response to it and the correction path is very different than it used to be.

Julian Zelizer: In terms of how the media’s doing, like always, there’s good and bad. I think there’s great reporting taking place. There has been a good reporting, and it is fragmented, but it’s there in terms of issues of corruption, about the impact of the current budget bill being floated by the House, that was passed by the House that’s being discussed by the Senate. There’s a lot of good coverage about foreign policy. There’s a lot of bad coverage. There’s a lot of moments we now know about, where organizations have pulled back from stories for fear of angering the president — that is certainly not a bright spot in the history of journalism. It’s a mixed bag.

I think of more kind of the moment we’re in, less about how the press is covering the president or the MAGA era, but the stresses that the institution faces, and they are immense. We talk about this as we sit, and we should say that in an institution that is under attack as we speak in very serious ways, an institution you all love, and I don’t just mean Princeton, I mean higher education.

In terms of the press, it is now operating in an environment where there are direct and explicit threats from the administration. Let’s just say what it is. Whether you support it or oppose it, that is what is happening, and that ranges from regulatory threats on a scale that I would argue even the Nixon administration didn’t imagine when they went after The Washington Post, to rhetorical threats of intimidation and delegitimization. That’s what reporters are operating on. That’s what owners are operating on. That is the reality of 2025.

How do you have good solid coverage when you are facing that every day? And some of the threats could even get worse. It’s not unrealistic to talk about the intimidation of reporters through all mechanisms.

A second challenge certainly that is connected, but separate, is the changes of how a lot of media organizations are owned. This was at the heart of The Washington Post issue with the endorsement and an alumni of our institution. And the question of when you have more media that is owned by businesses with many interests, and some of those interests are separate from freedom of the press, they’re separate from good reporting, but they can be subjected to forms also of punishment and intimidation, how does that affect coverage? There can only be so many nonprofit organizations at a given time, like ProPublica, which does such immense work, that I think it’s now an issue right in front of us. I think that’s a second concern, and you’re seeing this play out with the networks, you’re seeing this play out with print, and much more.

A third is a broader culture of distrust. The fact is, a lot of the public doesn’t like the press. We are another institution, I’m only a part-time, but I’m also another institution people don’t trust. I’m everywhere. There is a moment that there’s work that needs to be done by the press to regain the trust of readers, listeners, and watchers. It’s not enough just to complain about it.

I think it has to be a moment where reporters and producers of news think about, how can some of this be rebuilt? I think there is some interesting stuff happening. You mentioned the Substack and the podcasts. It’s a world where connections to individual reporters and hosts or voices of analysis is actually a mechanism where some possibility for regaining trust seems to exist. I don’t know where it’s going, but I think those kinds of conversations are important, because you need the public to gain public support. And it’s not there right now. For many reasons, some because of the press, some external, but it’s a reality that I think is part of 2025.

Finally, it is the issue of splintering and fragmentation, which won’t change. We’re not going back to an era of three networks and a handful of city newspapers. Not happening. I think, again, it’s a challenge because it’s harder to command public attention. Any story, no matter how great, no matter how revealing, is likely to be lost within the span of 24 to 48 hours, because there’s so much out there, or it might never even gain traction, because you don’t have to be watching.

I tell my students in 19 — pick a year, ’68, ’73, if the president went on to speak on television, if you wanted to watch television, that’s what you had to see, and the analysis that followed. Today, easy never to even look at it. Same with the story of great magnitude and importance. I think it’s a struggle, I’m not pessimistic, but it is a real challenge that’s not going away, and the media has to reinvent itself within that atmosphere. Those are four things I’m thinking about in 2025.

Mark Bernstein: I wanted to just follow up with one thing that Julian mentioned about the threat to journalists. Kathy, you’re at the Missouri Journalism School, and I think you’ve worked with some of the Voice of America Journalists, but could you talk about what you’ve been seeing?

Kathy Kiely: My chair is in free press studies so for those of you over a certain age, I’m not the Maytag repairman right now. It’s pretty busy. I’ll say a couple things about that. One is the Voice of America and all of its affiliated agencies — Radio Free Europe, Radio Free Asia, etc. As many of you know, or maybe you don’t, because it might’ve gotten lost in the mix that Julian described, the Trump administration has chosen to close down that source of, it was a great source of American soft power, and that leaves hundreds of journalists without jobs.

There are about two dozen who really will be betrayed, because they will be sent back to countries where they will be put in jail or worse because they’ve worked for the United States of America. We are working to try to help those journalists, but this is what you’re seeing. You’re seeing that is an actual existential threat to people who practiced the free press, and they are being put into a very scary situation by the government of the United States of America.

Mark Bernstein: Here’s a question that I apologize for what might be considered a little bit unfair, but Marc, you were on a panel, I think this panel, the PAW panel in 2017, and one of the questions that was asked was whether the press should call a statement by President Trump or President Biden a lie. Use the word lie rather than some other sort of softer descriptive word. I think you argued in favor of not using that word, and I’m curious whether you still agree with that, and how do you think that applies today?

Marc Fisher: The practice has certainly changed from Trump one to Trump two. At many news organizations, you do now see fairly routinely, the word lie being used. We’re still reluctant to use it in news stories. It’s certainly no problem in opinion pieces, and happens all the time in opinion pieces.

The argument against it, which I think is compelling, is lie is a slur. It’s a fact, but it’s also a slur. On a purely factual basis, we don’t know when Donald Trump is saying things that are false because he’s profoundly ignorant, or when he is purposely trying to mislead. We can’t know that, that’s inside his head. When you use that term routinely, first of all, it loses its power, but second, it speaks only to those people who are going to react to that by saying, “Yeah.” It doesn’t speak to the other half of the audience or whatever percentage you think it is, for whom it is antagonistic.

It’s not our job in news stories to be antagonistic. It’s our job to present the facts and let people, give people the ammunition they need to make their own decisions. Then in opinion pieces, call it a lie, make your case. I think we really do a disservice to readership and especially to the lost audience or the audience that we’re in danger of losing, because they see us as a partisan force. That’s something that we need to fight against at every turn.

Mark Bernstein: Anybody else have a thought about this, or no?

Kathy Kiely: I agree with that. I think that, this is the problem that I identified earlier when I talked about the norms on both sides of the press and the politicians being challenged. I almost think it’s like waving a red flag at a bull, and hoping the bull will run and gore itself into the wall. If we give up what, our stock in trade is facts, and our stock in trade is show don’t tell.

That is what we always tell young journalists. Don’t tell me somebody’s a liar. Give me the facts I need to know to make up my own mind. I think that has always been a hallmark of good journalism, and it always will be a hallmark of good journalism. But there are a lot of provocations out there that are testing those norms.

Peter Elkind: I’m not sure I agree with that point. I think there are many, many things that Donald Trump says that he has repeated year after year, time after time, which have been corrected year after year, time after time, which are very knowably false. It seems almost a little innocent to not be willing to call him out on it in a provocative way. I do understand, obviously, “show, don’t tell” is a central notion of credibility of journalism, but I don’t think that is responsible for distrust of the media, that sort of thing.

We spoke earlier, a discussion earlier about the lack of poor standing in the media, and there’s no question poll numbers are mortifying. I’m not sure how much of that is a result of missteps and failures by the mainstream traditional media, and how much of it is simply the withering, relentless attack on traditional media outlets by the administration, by conservative movement, by people who don’t like what’s fairly and accurately reported.

ProPublica writes stories we, I think, are studiously seek very hard to be studiously fair. We have a rule of any major story, you try, of course, to get comment from everybody, but before a story is published, even when you are being shut out and official sources won’t respond, or whoever you’re writing about won’t respond, you prepare what we call a “no surprises letter.” Detail all the findings of your story, give them an opportunity to comment with enough time to do so.

I’m not sure our practices are so horrible and responsible for the low trust of the media as sort of advent of approach by the administration of making the media a subject of relentless attack, sort of habitual response to a story by ProPublica from some quarters is, “Oh, it’s a George-Soros-funded outlet.” Yeah, George Soros gives some money to ProPublica, but so do 70,000 other people. It’s just a reflexive attack that doesn’t address the facts in stories. Anyway, that’s my two cents on that for now.

Julian Zelizer: Yeah, I’m predictably in the middle, meaning I think you can’t anticipate how your stories are going to land, and I’m also not convinced all the distrust is because of the press. Some of it is, but some of it is a systematic attack on and on and on about fake media, rigged media, which actually goes beyond Trump. It’s been for a while now, and it has an effect. I think it’s had an effect. So I think you have to focus on what’s good reporting and just stick to that. That’s ultimately what rises.

It’s difficult. I see lie as a word specifically that insists on an intentionality that might be hard to prove, and it might be wrong, which isn’t what you do. But incorrect information is accurate reporting, and you have to say it clearly to people, especially when they’re inundated with falsehoods. The job of the reporter is not just the opinion person to help distinguish when someone says something that is not true. We have learned this again and again.

The trick of Sen. McCarthy was to throw things out there, have their press just echo what he said, and then let the fallout happen. Vietnam, the early trick from the Kennedy and Johnson administration was to have the information funneled through military sources, and it took a while before they started to question, was that true or not, to disastrous effects; same with the war in Iraq. Meaning, I think there needs to maybe be other language, but it has to be clearly stated as part of the reporting.

It would be a kind of malpractice to somehow not point out in a story about the 2020 election that Biden won, and that when people kept saying to the point of violence, “He didn’t,” that wasn’t true. It wasn’t correct. That has to be somehow, I’m not a reporter, but it has to be part of the coverage, as does the effect to change.

Kathy Kiely: I think there’s a difference, and you’ve pretty much gotten there. There’s a difference between saying something is false, which journalists are doing, and that is provable, and that it’s a lie. Because a lie, as you said, involves an act of mind reading, and it is provocative because it involves an act of mind reading. Show me. This is what we always ask reporters, “Well, how do you know that? How do you know that? Give me a quote, show me the data.”

That I think is what needs to be done. I think the other problem, which has been talked about here, is that it doesn’t matter if prove something, if only a small segment of the audience is paying attention. It’s like the tree falling in the forest. If you are a viewer of Fox News, and a listener to Joe Rogan, and you read Zero Hedge Fund and Epic Times, you have a very different worldview than if you read The Washington Post or The New York Times, and listen to NPR and read The New Yorker.

That is, I think, that Balkanization of the audience is a real problem. It’s very difficult for us as journalists. I think that’s one reason I’m at a journalism school. We need to think about how we resolve that filter bubble.

Marc Fisher: I think to Julian’s point, we have failed as journalists to develop effective ways of getting across that this is false statement. It’s routine, it’s rote in every story, “This is false. Biden won the election,” but it’s there so frequently and so routinely that people’s eyes must glaze over. We’ve not developed an effective way to drive that home again and again.

The other thing that we’ve done that I think we need to really be honest about, is the news media writ large, here, I’m talking about the news media, have taught now two or three generations of Americans to not know what reporting means, not know what reporting is. I always tell, teaching classes, I always ask people to go back on YouTube and watch any half hour of CNN from the 1990s. Just pick any day.

What you see is what we used to call reporting, because you see reporters in the field, taking you to scenes and places and meeting people you would not be able to meet on your own. You don’t see groups of people yelling at each other, which has now become the definition in the popular mind, I think, of reporting. It is anything but reporting. Commentary and conversation have their place, but they are simply not reporting. They are second order, they are based on reporting. When you don’t have that basis being fed to people on a regular basis, they’re just noise.

Julian Zelizer: Can I just add one thing? I think we’re generally in agreement. I’m still more leery that you have to think of whether it’s sinking in or not. I think there’s a responsibility to cover it. I don’t mean endless fact checking, but stories should do what reporters have been doing much more of. You have to put it in there. You can’t anticipate, are you ultimately kind of losing audience? If it’s the right story, it’s the right story.

I also think it’s important occasionally on key issues to report the lie. There are ways to find out if someone intentionally is kind of going around information they know. That was the story with Fox News and the Dominion issue and all of that. It was interesting. They found evidence, they knew exactly what they were doing. I think those are important stories also, it’s a whole other level, but I think what Kathy said should be part of the coverage.

Finally, look, it is part of the political strategy. I still think if President Trump was in the room right now and was being honest, he’d say, “Yes, I’m shaping the narrative in a way that is effective.” You do need to kind of cover that, or you’re missing a big part of the political moment strategically of how he’s successful.

Kathy Kiely: Yes, but the Dominion Fox News story, a key player in that and ferreting out the information, was the court system, because those documents came out from discovery. You’re not going to get those on FOIA.

Julian Zelizer: No, I know.

Kathy Kiely: OK, so this is another piece of the puzzle. Watergate happened, yes, because of The Washington Post, but also because Congress followed up. When your institutions are knuckling under, you can’t just say, “Well, the press isn’t doing their job.” The press is doing its job, but Congress, there’s no sign of vertebrate life up there. If Congress and the other institutions in our democracy aren’t responding to those stories, then it is like the tree falling in the forest.

Mark Bernstein: There was a poll that showed that I think in the 2024 election, people who were regular consumers of news multiple times a week voted, I think, democratic by a noted margin. The people who didn’t consume news at all voted for President Trump by a large margin. There’s been now kind of hackneyed, sort of go to a diner in Ohio to try to meet Trump voters in that sort of thing.

My question is, do you think, does the media understand the MAGA movement, or are they sort of alien people you’re trying to connect with that you don’t fundamentally understand?

Marc Fisher: Both. There are woefully ignorant stories that are written, trying to discern Trump’s motives and the motives of his followers. There are also really intimate portraits of Trump voters that get at what is eating people, and why they’ve been so consistent in their voting patterns, and why they see a connection between voting for Obama in ’08 and voting for Trump in ’16, and the forces in their communities, globalization, and so on.

All of that is happening. The larger mistake or gap in the news coverage, I think, is in understanding how deliberate Trump is about taking advantage of that ignorance in much of his base. We’ve seen this before to one extent or another, Trump’s great mentor in life, Roy Cohn, was right at the right hand of Joseph McCarthy. Cohn argued and taught Trump at a very early age to make stuff up, throw stuff against the wall, see what sticks, and move on, and win the day, win the moment.

I spent a fair amount of time with Trump for this biography we wrote, and he was very frank about the fact that he threatens reporters, sues reporters and so on, with no intention of winning, no intention of having the better legal argument. Just as he never really cares what the policy is, he said his purpose in going after those news organizations and reporters was, as he put it, “To destroy them.” He does that both for sport and to just win the attention.

It’s very deliberate in that way, and he knows that his audience is less informed, so he can just make shit up. He’s very frank about that. When we were writing this book, he said, “I’m going to come after you if I don’t like the book.” He had earlier said he’s not going to read the book. Being a Princeton educated guy, I said, “How are you going to know it’s a bad book?” He said, “People will tell me.” I think people from our world often judge him and try to understand him through the lens of rationality and logic.

We were talking earlier about the past and things that he may have learned. That’s not how he operates. He, almost uniquely among people I’ve ever met, lives entirely in this moment. He gets this bewildered look on his face when you mention anything from the past, like, “That didn’t work when so-and-so did it,” just does not compute. The same thing about the future. He doesn’t think about the ramifications of anything he does.

Kathy Kiely: I’ve never thought of Donald Trump as being zen.

Marc Fisher: Yeah, he’s totally in the moment.

Kathy Kiely: I will say, I do want to underscore a point that Julian made about the threats and how they have helped erode, I think there are other structural reasons maybe that we could talk about for press, that lowering of trust in the press, but these attacks are not to be underestimated.

I think a great book written by Class of ’86, Maria Ressa, How to Stand Up to a Dictator, really outlines the dictator’s handbook that you can see being passed around from country to country. That does seem to be one book that Trump read, and not Maria’s book, but the dictator’s handbook, and this sort of relentless attack, an attack that lawsuits that really aren’t about winning, but about draining a company, a corporate, or an individual’s financial resources — this is part of the dictator’s handbook, but this type of reaction is trickling down.

We had a Mizzou student who went out and she was reporting for a local news outlet in Nebraska. She had a great story, an investigative piece about pollution from the hog farms. If any of you know what a CAFO is, you’ll know it’s rather odiferous, and there’s a lot of pollution that comes from these. One of the biggest polluters in Nebraska was a farm operation owned by the governor. When the story ran, reporters asked the governor about it, and what did he do? He attacked the nationality of this young woman. He said, “You can’t believe it because she’s from communist China.”

This is the kind of attack that’s going on. It was a totally legitimate story, but this is the type of thing that you’re seeing. It’s attack the messenger, pay no attention to the facts.

Peter Elkind: Yeah, I agree with all of that. On Marc’s point that Trump knows that he, and his playbook is to just make shit up, I think that’s very true, and it’s an argument for calling him out on that, not just in books, but where it’s pretty demonstrable in his daily day-to-day missives on Truth Social, and press conferences.

I also would make the point that, yeah, the threat to the press really is very real. Obviously, we see what’s going on at CBS, where 60 Minutes has lost its top news director and hands-on producer who’s there for decades because of concerns that there’s pressure from Shari Redstone, the owner, to kowtow to Trump in order to get the government to clear their merger deal, their sale, which is worth billions of dollars to her. It’s clear that the Federal Communications Commission chair is willing to make all kinds, he is making all kinds of threats about networks losing their licenses, because he didn’t like the way that stories were edited, among other things, and is weaponizing that part of the government as well against the media.

Then just as elite universities, Princetons and Harvards of the world are under assault in various ways, there’s threats to weaponize the IRS and revoke nonprofit status. ProPublica is a nonprofit organization. It’s not beyond the imagination for the idea that Trump doesn’t like stories that we publish, or other nonprofit media organizations, and to go after us, and try to revoke our status. That’s something that’s a matter of concern in our operation, and certainly would never have been before.

Julian Zelizer: I think in terms of the original question, I think there’s been more work on the Republican voting electorate that’s come out in recent years. Initially, some of it to me seemed a little silly. It was like, focus groups discussions, but I think they’ve gone more reporters into red parts of the country to understand the different issues that animate the electorate, more kind of qualitative, and there needs to be more of it for sure.

I think in general, we become excessively poll-focused in terms of how we understand the electorate. I think the more work we can do, and I know it takes money and resources, so that’s a problem, but to go into different parts of the electorate and really have reporters unpack what’s going on. It’s not simply MAGA Republicans. It’s even, look, we caricature Democratic voters. Many Democratic voters are not latte-drinking East Coast elites, sitting around university towns.

This is not the fact, and I’d like to know more about that electorate. I like to know more about the people who are the sliver of the independent swing voters. I’m just saying, I think the polling only gets us so far in understanding where the country is. It’s tough because you need money to pay people to go out and do that, rather than sitting in their office and looking at numbers, which is good work, but it’s a different kind of work.

I would say, A, that kind of reporting, they’re doing, we need more of it. It should be funded and supported. It’s incredibly important understanding where we are politically. Secondly, just another broader kind of challenge, it’s capturing the surreal nature of some of the things that are happening. I am not a historian who goes on TV all the time and says, “Unprecedented, unprecedented, unprecedented.”

I wrote an article saying it’s overused, but there are parts of it that are that way, and it’s important to capture. Quickly, I was at a meeting just so you understand what’s going on here, at the end of the semester, where it was a faculty meeting, and our entire agenda was A, about what to counsel graduate students who are scared about being deported, and where they can get legal resources, B, what do you do if ICE comes into your classroom? I’m not sharing secrets here. A lot of universities are having this, can you let them in? What room can they come in? What do you do?

I’m sitting there, this is, like, “What?” It was a surreal moment where we’ve landed. I do think in a way, reporters do it carefully in showing there has to be a way to capture some of the unique elements and unsettling elements of where we are politically today beyond the university. I’m just giving that as an example. Those are just two responses.

Kathy Kiely: I would just add to that to say that at the University of Missouri, we had people checking the SEVIS site, which is the site for student visas, three times a day, because that’s how quickly student visas were being lifted without any notice to the students, and then they could be picked up and detained. That’s very real.

Mark Bernstein: I’ll ask one more question, then we want to leave time for audience questions as well, but the story of the last week or so has been the revelations about President Biden and the lack of coverage of his possible cognitive decline over the last year or so of his presidency. I’m wondering, what do you think about the media’s coverage of that, and does that coverage or lack of it in any way perhaps illuminate how the MAGA movement is being covered or not covered?

Marc Fisher: You can go back and look from an early 2024 terrific piece of reporting by Annie Linskey in The Wall Street Journal, that spelled out in enormous detail, Biden’s incapacity. It was a tremendous reporting challenge, because the people around him were working overtime to cover for him. The stories are there, and although the popular perception is that they aren’t, and they didn’t hit home, and they weren’t frequent enough, and so on, I would argue that they did hit home.

If you go back and look at the polling, you have two solid years prior to that election, where north of 75% of Americans said they didn’t want either of those guys to be on the ballot, neither Biden nor Trump. First of all, you had remarkable consensus in this supposedly permanently and awfully divided country that nobody wanted either of those guys.

You had, I think people had absorbed, through their own observation and through some media coverage, that President Biden was not up to the job or was no longer up to the job. I think people have a pretty good spidey sense about these things. Just as many, if not most Trump voters knew from the start that this was not a guy you’d want to have a beer with, and this was not a guy who you could trust with, to babysit your children, they had other reasons for making a statement. The same was true with how people absorbed the facts about Biden’s condition.

Kathy Kiely: Yeah, I agree with that.

Peter Elkind: I’ll agree with that. I do think there’s a big component of that view being reinforced, and amplified, and declared by Trump and his supporters. Democrats, I think polls showed, felt the same way, and that is significant. No question about it.

Julian Zelizer: Yeah, I’ve been reading the stories, and I think it’s an interesting and important story. I don’t think it’s the only story. I worry it gets excessive attention relative to other big things that are happening right now, which is a fair criticism. I think, I don’t know, it’s a major part of what happened in the election. I’m totally, I think it’s good coverage.

The second part of your question would be the attention issue, meaning this whole debate about the politics of attention. Chris Hayes wrote a book about it. I think it’s getting a lot of interesting conversation that the real commodity in politics is what can you hold the public’s attention on as much as possible? President Trump’s excellent at this. I just think of how does this story fit in that world, given all the other very important things happening in real time right now?

How many people know about that relative to the crypto dinner that just took place in the White House to reward investors in the company? It’s an important story, and I think overall, reporters are doing a good job, including Jake Tapper and the new book about it.

Mark Bernstein: We’ll turn it over to questions from you. Raise your hand and we’ll pass you a mic. The one, just a preface I wanted to make, which I stole from Anne-Marie Slaughter [’80] yesterday, is the emphasis is on asking a question, not making a statement, and then following it with a declarative, do you agree? Please ask a question. Over there. Well, actually, up in the back there. Yes. Yeah, we’ll bring you a mic. We’ll try to get around the room.

Audience member 1: Hi. Hi, there. Thanks for this. This has been really interesting. I graduated in 2016 right after Kathy, you resigned in protest from your job at Bloomberg for how Michael Bloomberg was allowing you, your team to cover him and his run for president. I’ve been thinking about that recently actually, because of a story that Peter mentioned of CBS News Director Bill Owens resigning in protest because of how CBS was allowing him to cover, or his independence, his team’s independence in covering Trump, etc.

I’m curious how you guys are thinking about the act of resigning in protest these days, where somebody else can come in and not cover as aggressively these topics that journalists feel should be covered more aggressively.

Kathy Kiely: Well, I’ll start, because I did do that. I was talking to Peter Barzilai [s’97], the PAW editor, about this just earlier this morning. I think when something like that happens, somebody has to resign. I had a lot of great reporters who were working for me, and I counseled them that they did not have to resign. I said, “You will be able to do an honorable job covering your particular candidate.” I was the political editor, and I was the person who would not have been assigning the stories about Mike Bloomberg that we should have been assigning.

My particular role required me to take a stand on principle, and my life station, I didn’t have anybody depending on me at that point. But I do always counsel my journalism students, and I think this is probably a good counsel for anybody: It’s hard to do, but one of your life goals should be to have a stash of FU money, in case they want to say FU to you or you want to say FU to them. It’s a very handy thing to have.

Audience member 2: Hi. I’m curious your thought on the proliferation of right-wing podcasting spaces and the efforts of people like Gavin Newsom to kind of integrate himself into those spaces. Is that effective? What are your thoughts on combating the rise of the right-wing podcast?

Kathy Kiely: You’re the podcast king.

Julian Zelizer: Sure. I don’t think it has to be combated. I think rather, they’re being very effective. I think it’s been an area of the media that has succeeded, and I do think there’s pressure now, whether it’s center, liberal, democratic, whatever, to figure out what the platforms offer that can be done well. I think there’s some people trying to do that.

A lot of people listen to Ezra Klein, I’m sure, who is one model of a very thoughtful, certainly left of center alternative to some of that work. I’m not sure. Look, if Gov. Newsom wants to do it, God bless. I don’t know how effective it is. I don’t know for his own political aspirations, if it matters. Someone just sent me, Pete Buttigieg went on some kind of two and a half hour conservative-leaning podcast, and he was excellent. I watched, I couldn’t believe how good he was. He did actually show how you can have a conversation in that kind of room.

I don’t think of it as destroy it, and I don’t think people should think of it that way. I think that’s a kind of example that has to be studied, understood, and there has to be just a broadening of offerings as part of the media platform. Not all of it, because it’s not vetted, it’s not produced, edited, but I do think it’s part of our world.

Again, back just to end, the connection people form with the host is really interesting. People trust Joe Rogan. He’s not exactly just a right wing, by the way. He’s a little more complicated. There’s different ones, but there’s a trust and a connection that I think you can say Walter Cronkite used to have in a very different way that is actually going to be important going forward in the media.

Marc Fisher: There’s something cringey about what we’re seeing now. There’s a sort of formal, well-funded effort among liberal organizations to find the liberal Joe Rogan, which reminds me of a similar foolish endeavor back when Rush Limbaugh was the king of right wing media, and there was a similar effort called Air America, which was supposed to be a shouting populist kind of liberal retort to right wing talk radio. It was a total disaster.

What it revealed was you already have the left wing version of right wing talk radio. It was called NPR. It gets back to that division between the rational, policy-oriented, fact-oriented audience that wants the reporting of something like NPR, versus the right wing audience that wants somebody to express their frustrations.

It’s like the difference between the democratic policy elite, which is almost all lawyers, and therefore thinks about and talks about issues the way a lawyer would, whereas, I think it’s nine of the last 10 Democratic presidential candidates were lawyers, and none of the Republicans were. That reflects a real difference in the way each party talks to the country.

Julian Zelizer: There’s also some, I’ll just add, some non-left or right podcasts that are really good. Someone told me about this Left, Right, and Center podcast. Now I listen to it all the time, and it’s really thoughtful discussion. It actually gets you the different perspectives of these different questions. I think it’s not only a problem, this new space. There’s some really good work. It’s not reporting as much as commentary and analysis so far, although there’s good reporting on some of them.

I don’t know. It’s a platform I find very good. It shouldn’t just be a political positioning platform, which I worry about. It can actually be a way to get and think about news, whatever your political perspective. That’s very useful.

Mark Bernstein: Question, Bill. Right on the aisle there.

Audience member 3: Thanks, Mark. I owe you a beer at the tent. Hi, Bill Bandon from ’83. Much like on the economic side with Trump, where the bondholders in the bond market reined him in on some of his economic work, are there other institutions that could play here in terms of reflecting some influence in steering dialogue toward truth, toward pushing back on falsehoods?

Do you see any other places that, not so much that aren’t under attack, but as I said, institutions or organizations that might actually be able to start boxing in either the MAGA organizations that are putting on falsehoods, or the president himself?

Kathy Kiely: All of those organizations are under attack or will be. The most important organization is the unorganized, I’m looking at them. I think it’s really, really, really important for voters to make their voices heard, and not just when you go to the ballot box. It’s very important. We talked about Gavin Newsom or Pete Buttigieg going on Fox News, which I think is very smart.

I don’t care how divorced you feel you are from the viewpoints of your elected representatives. You might feel very divorced, because if you live in a place like I do, you’ve been gerrymandered to death, but you need to reach out to your elected officials and tell them what you think, because they listen. They really do listen to constituents. It’s very, very important for, if your public radio station is threatened, if your university is threatened, if your favorite investigative news outlet is threatened, it’s important for you to make your voice heard.

Peter Elkind: I think the question is, what influences Trump? What moves him and what can move him? That’s really pretty tough these days.

Kathy Kiely: Public opinion.

Peter Elkind: What’s that?

Kathy Kiely: Public opinion.

Peter Elkind: Yeah, no, that’s where I’m going is you think of things that have prompted him to change his position. The bond market reaction to the tariffs prompted him to change his position until he changed it again and again and again. The stock market at some point is beyond denial in terms of what direction it’s heading. The economy numbers at some point presumably are hard to continue to distort, to stop saying, “The economy’s better than it’s ever been. We’ve never seen anything like this.”

Those things, and polls, of course, as Kathy says, clearly he cares about that. There’s a lot of falsehoods about, false statements, falsehoods, or lies, depending on how you want to characterize it, about his standing in the polls. Then the other element that seems to move him fairly swiftly is people like Laura Loomer, those people from the far right who attack him for not being MAGA enough or not true enough.

Obviously, her perspectives and complaints and Steve Bannon’s, people like that are often personal and self-serving. That seems to move Trump pretty swiftly in terms of firing some people. It’s a tough one to figure out.

Julian Zelizer: I guess I would say, to Kathy’s point, the first year of the Trump presidency, I had a dinner with a very, very conservative Republican who you would all know, and I happened to have dinner with him. Then a little later, I talked to a former student of mine here, Ezra Levin [*13], who founded Indivisible. They both agreed, both of them, that the key to political pressure is local rather than national, that it really has an effect what members hear. It’s not irrelevant. They listen when they’re kind of confronted with pressure via phone calls, texts, or rallies. It’s an interesting commonality. I remember them happening at the same time, almost.

Secondly, I think if you’re someone who, it’s not a left-right issue, it really isn’t. If you’re someone who’s pro-institutional stability, rule of law, and just protecting the elements of American democracy that we love, and you can be a Reaganite conservative, you can be a Sanders liberal, whatever, that doesn’t matter. It’s about the process and mechanisms.

I think everything all of you said is important, and I still think Congress is making a choice right now, and the pressure, and it’s narrow majorities. The pressure that certainly purplish Republicans face right now will have an effect. They are looking at the midterms already, and I can tell you, they are concerned. I do think there’s pressure points in Congress that still matter, it’s not an irrelevant institution. It’s an institution that is proactively deciding to do nothing the majority right now.

The question is, if you are concerned with these kinds of issues, can you move them? Look, when this all started and the president started cutting the funding through DOGE, he pulled back a bit when Senate Republicans said, “Stop.” That’s another voice he will listen to, because they have power if they want to use it. Real power, enforcement power. I would just add that to the mix, especially the purplish Republicans right now.

Mark Bernstein: The gentleman up there with his hand raised. Yeah, you, with the P.

Audience member 4: Thank you. My question, a few of you mentioned that a good element of journalism is the show, don’t tell, and it feels like you can show a lot of conservatives as many facts as you want, and they’re never going to hear them or see them or anything. Where does that land in your landscape of reporting? Is there something that you’re thinking about with that? It just seems really disheartening to me, so I’m wondering what you guys think about it.

Marc Fisher: It’s a core issue. It’s deeply concerning. You see a lot of individual reporters taking a lot of creative approaches to stories, writing about the home lives, family lives of voters who live in news deserts or information silos, but of course, who’s reading those stories? How do you break through? One way you break through to Trump is you go on Fox News because you know he’ll be watching. I think similarly, to reach the hardcore right-wing siloed audience, you have to go to where they are.

You do see some Democratic members of Congress going on Joe Rogan and that sort of thing, not a lot. They’re still driven primarily by fear of being insulted or attacked. As far as reporters go, it’s an audience question. The creative approaches to stories are being tried, but I don’t know that they’re doing much good, because they’re not reaching exactly those people you’re talking about. It’s hard to think of any outlets that are specifically looking to cross that divide.

There are all kinds of civic groups out there that are trying to stage conversations across that divide with some success, but a drop in the bucket.

Kathy Kiely: It’s going to take a while. I think that’s absolutely right. It’s going to take patience and money, because I think one of the problems is a lot of people who don’t trust reporters don’t see reporters. It’s the decline of local news. When they are able to have a relationship with somebody, it makes a difference. I sent students out this year to a town called Centralia, which is a very rural town, kind of a rural crossroads, about a half an hour from the college town where I live.

As one of the guys there told one of my students, Columbia, our town, might as well be a thousand miles away. Very different people, very different values, very different voting patterns. At the very end of this reporting project, as always happens in the media, as you know, we’re not organized enough to have a conspiracy, suddenly this story was going in the paper tomorrow, and I needed to get some pictures.

I didn’t have a regular student photographer available, so I sent a journalist in residence who is a Kashmiri photojournalist who would be in jail if she weren’t at Mizzou. And she’s Muslim. She went out with another, a student who is half Vietnamese and half some other nationality. These two women of color, both Muslims, went out and interviewed these good old boys who looked like they were right out of Orange County Choppers, big Trump supporters.

At the end of the class, the Orange County Chopper guy wrote in, I see all these transcripts, the student did an exit interview and he said, “Did you get an A on your project? I think you deserved an A.” He said, “I’ve really enjoyed talking to you.” One by one. But that is, it’s slow cooking.

Marc Fisher: It’s really easy to destroy that infrastructure. It’s really hard to build it back up again. There are some really interesting studies of the impact of news deserts, communities that lost their county weekly or their daily newspaper, and now have no regular daily coverage of local public affairs. There’s a direct line between that and lower voting turnout, fewer candidates running for office, and less interest in all things local.

Mark Bernstein: Over here, the gentleman there in the vest.

Audience 5: Thank you. My comment and question is just about civic education, because it’s just so striking that people seem to understand what the role of an independent judiciary, our system of checks and balances, or know anything about things like the spoils system and why we have a civil service, which is to make sure it serves the people rather than the president.

I’m just wondering what you see in terms of civic education or the lack thereof feeding into our current problems. My theory, which I’d like your view on, is just that these problems were always there, but maybe in a less splintered environment. We still were operating from the same set of facts or information. Therefore, that problem was more muted.

Julian Zelizer: I could jump in. I think I could be a little cynical and say, you can teach all the civic education you want. Doesn’t matter that the kind of power of partisanship, the power of the information economy is overwhelming once you’re an adult. It doesn’t really matter. It’s not about do you know about the balance of power, or do you know about the separation of the branches? It’s more, do you care? Do you know there’s corruption and why that’s a problem, or do you care?

I think there is a cynical answer, that it’s limited, but obviously, I devote my whole life to civic education, and the more of it, the better. I think it’s important at all levels that, again, it’s kind of like what I was saying in the media, regardless of how effective it will be as an immediate tool, it’s a value added we need to continue doing.

I do think, I’m often asked, “Why don’t young people care about these issues anymore?” Similarly, “Why don’t young people care about the media?” It’s not simply a conservative red thing. I think we’re way beyond that. It’s a generational issue too, and that’s all true, but then part of it’s on us to figure out ways to make it not just available, but accessible and interesting. In civic education, I think teachers need to think of that as well.

It’s not simply giving a pile of information that will somehow change the kid by the time they reach high school, college, and upward. The commitment has to be on us just like reporters to innovate, and to find ways to communicate this information that matter, that are meaningful, and that will stick. Maybe 5% of it, but still that will stick and matter in their lives. It’s not simply having more of it. It’s how do you do it? I think good teachers are working on that. I certainly try to do that here at Princeton.

But I do think that’s the mentality, rather than just blaming, and I’m not saying you’re doing this, but rather than saying, “Ugh, kids don’t know anything anymore,” it’s like, “Well, why aren’t we doing it in a way that they do?”

Kathy Kiely: I’m going to say the changing of the media ecosystem has had an impact, because when I started out as a reporter, we covered the state legislature regularly. We covered Congress regularly as a serious institution. If you get your news from cable television right now, which a lot of people do, you would think there was one elected official in the United States of America.

We need to reteach people where the levers of power really are. I don’t care if you vote for Donald Trump or Barack Obama. They’re not going to fix the potholes. They’re not going to fix the schools. There’s a different set of elected officials who do that. We need to start, and I think one reason people are so frustrated is they vote for one guy or another and then they say, “Well, it didn’t change my life.” “Well, did you vote for school board? Did you vote for state legislature? Did you vote for Congress?” Believe me, I talk to students, they don’t.

I am on them all the time. “It’s the midterm elections. Have you gotten your absentee ballot yet? When are you going home to vote?” I gave a kid a day off so he could go home to vote. I just think we need to get better about reminding people that the president doesn’t do everything.

Julian Zelizer: We do, I want to just stand up for the young people. There are a lot of still very civically-minded young people. I have had them here. I see one sitting right near you who’s doing great work. Hello, Laura. I have a student, Virginia Maloney [’10], who’s running for city council right now who has, the primary’s in June. I don’t know, I meet Republican Democrats, I’ve had a lot of students.

I get it’s declining, I get, but there are still really good people who have those instincts. We should also focus on working with them to move them and to keep them in that realm. I want to give young people their fair due. And there’s more I think than we often acknowledge.

Mark Bernstein: I think we have time for one more quick one. How about the gentleman there in the jacket?

Audience 6: Hi. We’ve been talking around and about one person, and I would like to know if you have any sense of, he’s obviously going to leave the scene at some point, I don’t know how, but do you have any sense as to how this illness will continue once this very charismatic and gifted attention grabber is no longer part of our scene?

Julian Zelizer: I mean look—

Kathy Kiely: You’re the historian.

Julian Zelizer: Well, the historian, look, I’ve written about this and let’s put aside the illness word. OK, that’s a position and that’s fine. In terms of the politics, let me answer it that way, surrounding what kind of gave rise and what facilitates President Trump, and his reelection, and his politics, it’s very deeply rooted. It’s true, that you can see the change in the Republican Party taking place over decades.

We were writing about this before Trump was on the scene, first with the Newt Gingrich era, then the Tea Party Republicans. There has been a shift in terms of policy. There’s been a shift in terms of political style. All the questions about the media, it didn’t start in 2017. I teach a class that goes back to the ’70s that kind of tries to walk you through how it splintered, how the news cycle changed, how commercial incentives became much more important in different ways to the press, etc., etc.

It will go away in that he is a very distinct figure, and he does it in his particular way. But I think a lot of what he does in terms of policy, it’s logical. It’s not as if the Republican Party shifted on immigration, for example, in 2017. You can go back to the 1990s in California and Gov. Pete Wilson and see that shift already happening even in terms of the partisan style that’s happening.

So I don’t think it’s going to disappear. I do think this is pretty deeply rooted in where our politics is right now. If you’re kind of concerned about that and don’t like it, it has to be a much more deeply rooted approach to tackling some of this.

Peter Elkind: One quick point I’d add is I think there’s also important structural changes in the country, and the legal structure, and system, which gerrymandering obviously being a big, big factor, that has made it easier for a politician to be extreme on either side. It could have happened with a very far left politician, because his followers, his supporters have no fear given the environment. At least they would have no fear if the situation were reversed, of losing in a general election. They don’t have to be as reasonable, or moderate, or try to reach accommodations. Similarly, the influx of dark money has clearly transformed the political system in a very systemic and ongoing way.

Marc Fisher: To me, the big question for the post-Trump era is will the political system, will voters allow politicians to go back to being boring? Trump is a creation of the entertainment culture, and you see a number of politicians, both parties, trying to mimic that rhetorical style, the sort of populist style, but most politicians are still kind of Bob Dole. They talk about bill numbers, and bill names, and things like that.

Will we as a populace tolerate a return to that kind of rhetoric, that kind of language? Given our dependence on entertainment, I have my doubts about that. On the other hand, most people who go into politics are not Marjorie Taylor Greene and don’t have that desire or ability to speak in a purely entertaining fashion.

Kathy Kiely: I would agree with all of that, and I would say that there’s always going to be, the problems that we’re looking at right now in this society that are in some ways catalyzed or embodied by Trump, are much more structural. I think Peter hit on a couple of them. The other thing that strikes me as somebody who lives on the San Andreas Fault line of political polarization, the biggest divide in the country right now is urban versus rural. Everything else seems to flow from that.

As somebody who grew up in the Midwest, in the industrial Midwest, and now I live in the rural Midwest, I have to say there’s a whole part of the country that feels left out and alienated for very good reasons. Until we manage to understand that as the media, by the way, some very large number, I can’t remember the statistic, the Columbia Journalism Review did this, but some enormous number of percentage of reporters live in five cities, five metropolises. And so we’re not really tapping into what created Donald Trump. And we have to do that, not just we the press, but also we as a country have to start to understand why.

The story isn’t Trump. The story is why did people vote for him? That’s what we have to understand.

Mark Bernstein: Thank you. Thank you. Please give a round of applause for our panel. Thank you all for your time, and thank you all for coming.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and SoundCloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

Paw in print

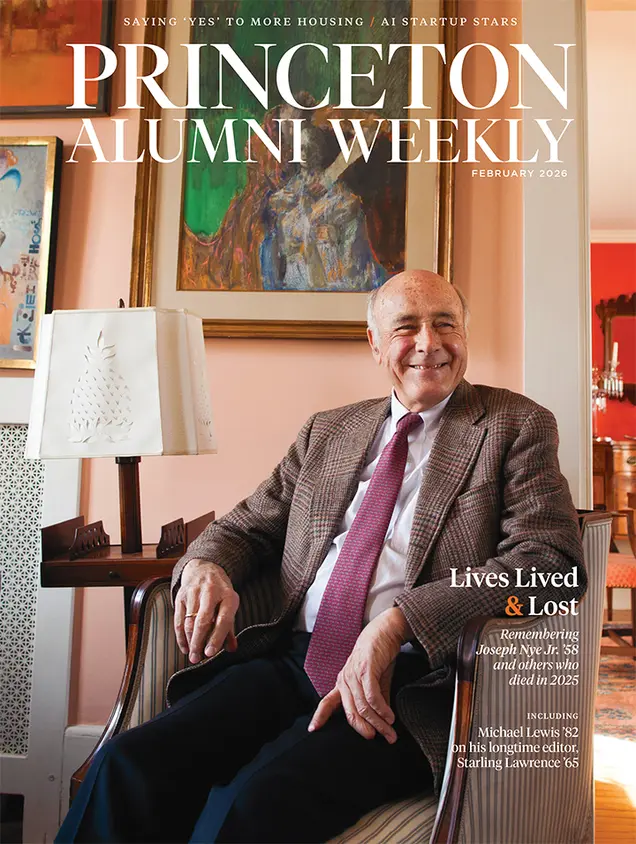

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet