PAWcast: Carlos Lozada *97 of The Washington Post

A nonfiction critic talks about how he reads books — and recommends a few recent favorites

Washington Post nonfiction book critic Carlos Lozada *97, a Pulitzer Prize nominee earlier this year, tells PAW about his approach to reading (and re-reading) books and shares recommendations from his own shelf. He also remembers the books that made a lasting impression on him as a kid. And he recalls his time at the Woodrow Wilson School, where he took macroeconomics from future Fed chairman Ben Bernanke.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

This is part of a monthly series of interviews with alumni, faculty, and students.

TRANSCRIPT

Brett Tomlinson: I’m Brett Tomlinson from the Princeton Alumni Weekly, and you’re listening to the PAWcast.

Our guest this month is Carlos Lozada from the graduate class of 1997. He’s the nonfiction book critic for the Washington Post. He joined the Post in 2005 and covered economics and national security before beginning his current role in 2015. He has received a National Book Critics Circle citation for excellence in reviewing. And earlier this year, he was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in criticism. And if my exhaustive research is correct, he also is a past champion of the Washington Post table tennis tournament. Carlos, thank you for joining me.

Carlos Lozada: Thanks for having me. That was definitely the highlight of my time at the Post — winning that tournament. I got a Starbucks gift card.

BT: Excellent. What was the table tennis scene like at Princeton when you were there?

CL: I lived in the Graduate College for my first year. There were a couple of tables there that we would sometimes hit after spending time at the DBar. So it was what you would think it would be, for a bunch of graduate students.

BT: Well, I’d like to obviously talk with you about the work that you do. But to begin, could you tell me a bit about your background at Princeton? I mean, you were a master’s student at the Wilson School. What did you hope to do? What did you expect to do? And was journalism on your radar at that point?

CL: Journalism wasn’t on my radar at all. I went to Princeton after getting sort of a traditional liberal-arts education at Notre Dame. And at Princeton, I was hoping to get a deeper grounding in the analytic policy tools of economics and social science. And my thought was to return to Peru, where I’m from originally, and maybe get involved in working at the Central Bank there.

And after Princeton, I worked at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta for a few years. It was great because the man who years later would become the Fed chairman was my macroeconomics professor at Princeton, Ben Bernanke. But journalism was not on my radar at all. I just realized, after spending some time at the Fed, that I was not — that it wasn’t for me. I wasn’t so interested in banking, or finance, or central banking. And I’d written, just as a hobby, for the Atlanta paper, for my Notre Dame alumni magazine. And I thought maybe, you know, maybe that’s what I need to do be doing. So I moved to Washington, got a job at Foreign Policy magazine. I was there for five years, and eventually made my way to the Post.

BT: And what about working in books and book reviewing? Why were you, why did you feel like that was something you wanted to do? And why do you think that it suited you?

CL: It’s funny, I think some careers only make sense in hindsight, when you see how A led to B led to C. I mean, I’ve always been a pretty devoted reader. But so are a lot of people. That doesn’t mean I have to become a book critic. I edited our coverage of economics and national security at the Post first, and then for five years, I was editor of our Sunday opinion section, Outlook, and had a great time doing that. But by 2014 or so, I sort of knew that I wanted to try something different. And I wasn’t sure what it was going to be. And then our long-time book critic, Jonathan Yardley — long-time meaning 30-plus years — announced he was going to retire. And so I just thought, that would be really interesting. That would be a fun thing to try, to try to do differently. You know, there’s been so much change and innovation in journalism, but literary criticism, book criticism, is kind of, it hasn’t changed all that much. And I thought it’d be fun to try to give it my own imprint, if I could. So I made a pitch here to the bosses, and they let me do it. And it’s been a blast. It’s been really fun.

BT: Take me through your day. I gather there are quite a few books that are coming in. What’s a typical day in the life? And how do you sort through it all and decide what deserves a review?

CL: Yeah, that’s a great question because I didn’t realize when I started the job — you know, I figured my time would be divided between reading and writing, right? And a lot of time is actually devoted to thinking about what to read and what to write about. I get deluged with unsolicited books coming in. I go to the mailroom — I think I may be the only person at the Post who goes to the mailroom every day. And I sort through anything from 30 to 50 books that have come in. You know, publicists, agents, authors themselves, they’re constantly pitching me.

I can’t be hostage to the new. You know, I have to decide what I think is important. And some of that may be obvious, like former FBI director James Comey has a book coming out. I’m going to write about that book. But what I’m trying to do a lot of now is to tackle thematic issues, like there’s a big debate about what’s happening to truth in America. And so I read five different books that are coming out, or that have come out over the past several months, that take different looks at that. I did the same with books about the United States and Russia — some that focused very deliberately on Trump and Russia, some that take bigger, longer-term perspectives. And so that way, I feel like I’m setting my agenda a little bit, rather than letting whatever the publishers are doing determine how I spend my day. But other than that, it’s a lot of reading, re-reading. Sometimes I read other books that I’m not reviewing but that I feel will give me the background I need to review a book that I am reviewing. So it’s a lot. It’s a lot. Writing takes up relatively less of the time than reading.

BT: And I’ve heard you, in another interview, speak about your process of reading and re-reading. Can you walk me through that just a bit and let me know, why do you think that process works for you? And why do you think it’s important to do that when you’re evaluating a book?

CL: Sure. It’s a process I think I came up with almost just accidentally. I started doing it that way, and then I just kept on doing it that way. I don’t know, it’s probably not the most efficient way for me to read, but it works for me.

I basically go through each book that I’m reviewing three times. First, I just read it straight through, with a pen, making a lot of notes in the margins, reactions to things. A lot of underlining and cross-referencing and checking footnotes, you know, and that’s the most thorough read that I give it. When I’m done with that, I hopefully put the book aside for a little while. But then I pick it up again with a highlighter. And this time, I read it again, but I focus on the stuff that apparently I seized on during the first read. So I look at the notes that I made. I look at the things that I underlined. I look at the passages that I felt were most significant. And then with the highlighter, I sort of cull those. And I focus on the ones that I think are really important. So that way, I’m done with the book a second time. Then I open up a file and I go through the book again, looking just at the stuff that I highlighted and come up with a subset of that so that when I’m done with that process, it may be a 400-page book, and I have maybe 3,000 words of notes and quotes and ideas from the book. And then that becomes my raw material for the review.

Once I’ve done all that, I feel like I know the book really well. And the writing process is actually relatively quick once I’ve gone through that incredibly painful, arduous process of reading and re-reading the book, especially when I’m doing a review that maybe hits three or four or five different books. That first series of cuts takes a long time. That may not be the way to do it. It’s the way that works for me. I don’t really know how other critics do it. But what I like about it is that an author of a book, or another reader of the same book, can take issue with my conclusions or thoughts about a book. But they can’t really say that I didn’t engage with it deeply and take it seriously. So I think that’s why it works.

BT: And while the Post is, of course, a national and international publication, Washington is, to some degree, kind of a company town. People care about politics. People care about policy. How much does that shape the way that you approach not just choosing books but also how you review them and how you approach them?

CL: Yeah, I think that there’s a heavy diet of political coverage for me, especially being the nonfiction book critic. We have a wonderful critic who focuses on fiction, Ron Charles. When I started the job in January 2015, I figured it would be a nice mix of memoir and history and economics and some politics. But like so much in the Trump presidency and our current moment, that became a really dominant focus. And so politics is a huge part of what I write about. Sometimes, I feel like I’m a political writer masquerading as a book critic. It sort of started in that summer of 2015, when Donald Trump suddenly caught fire and began to lead in the polls very quickly. So I had this idea that I talked over with one of the editors here. I said look, I just want to read a bunch of Trump’s books. Not just The Art of the Deal, but he’s written — or he’s authored, published — maybe like 18 or 20 books. And so I just want to read a bunch of them and see what’s there. And my editor said, “That’s a great idea. But do it really quickly, because who knows how long this interest is going to last?” So I did that, and there was such a response. I ended up reading eight Trump books, including the three memoirs, Art of the Deal and Surviving at the Top and Art of the Comeback. And there was such an intense reader reaction to that that I said, well, I’m going to keep exploring this further. And it’s not just books about Trump, but really books about populism for instance, right. Books about the white working class, books about identity, books about misogyny. All these things seem to end up relating to where we are politically right now.

BT: Do you see your job as sort of a service to the people who aren’t going to have the time to read all these books? To kind of give them a good survey of some of the arguments that are out there?

CL: I think that’s a big part of it. I think that people don’t always read book reviews in order to decide what books to read. They read book reviews so that they don’t have to read the books. That’s how I consume book reviews. You pick up The Washington Post on Sunday or The New York Times or the Wall Street Journal. You go through their book section, and it’s not like you’re going to run out and buy a bunch of those books. You may decide to buy one a month. I don’t know. But I think that, I see my job as, in part, letting people know not just what new books are coming out but even sometimes what old books are relevant again and matter once more. And so I definitely see a reader-service aspect to what I do. It’s a little different sometimes from other forms of criticism, where it’s much more pegged to the movie that’s out this weekend or the TV series with the amazing finale that is coming out now. I feel like I have a little bit more freedom to range when it comes to time. If I don’t hit a book right when it comes out, I can come back to it when I’m looking at several books that deal with similar themes. But yeah, I think a lot of journalism is reader service. And so I definitely see that as part of my role.

BT: I wanted to ask you a bit about recommendations. What is on your bookshelf right now? What are you looking forward to? Or what are you reading?

CL: I have this pile of books on my nightstand that I think of as my shame pile. You know, books that I’ve always felt I should read, but I never get to. And they’re just staring at me every night. But if I think about some of the books that I’ve been struck by and that, in the last three-plus years in this job — I don’t do this year-end round-up of the best books. I try to do a most memorable books, books that, for better or for worse, I think years from now I’ll remember reading. And one of those actually has a Princeton connection. Matthew Desmond, professor of sociology at Princeton, wrote Evicted. I’m hardly the only person to like that book. But I was one of the early ones to start touting it. I think it won all sorts of prizes. It’s an amazing look at Milwaukee and a community that lives under the threat and reality of eviction. Desmond spent a lot of time there interviewing, living with, hanging out with renters, with landlords, sort of in the midst of Great Recession kind of period. And it’s just an extraordinarily reported and written book. That’s the other thing, too, is like a sociologist who writes like the gods. It’s almost unfair.

A memoir I read in the last couple of years that I really liked was by Tracy K. Smith, the poet laureate. Also actually, everything has a Princeton connection. This was not a setup, I promise you. Tracy K. Smith, who’s an English professor, or a creative writing professor, I believe, at Princeton, but is the U.S. poet laureate now, wrote a wonderful memoir called Ordinary Light. I’m embarrassed to say I’ve actually read little of her poetry, but I loved reading her memoir about grappling with faith in relationship with her mother. It’s just a very spare, tightly written but very revealing memoir that I liked a lot.

There’s a book called, and this is more in the political vein, called The Speechwriter, by Barton Swaim, which is just a wonderful look at being a speechwriter for a governor, for the governor of South Carolina. Everyone remembers Mark Sanford for having his famous Appalachian Trail moment where he said he was out hiking, but he was actually with his girlfriend in Argentina. And Barton Swaim was his speechwriter. He wrote every speech that Mark Sanford delivered, except, of course, for that one. And it’s a wonderful look at political communication. It’s a slim little book. It kind of came and went. I don’t think it got a ton of attention. But it deserves it.

And recently, just as far as the summer goes, as I mentioned I read several books on the United States and Russia and several books on truth and politics today. And in that set, I really enjoyed The Road to Unfreedom by Timothy Snyder, who also wrote On Tyranny, that came out maybe a year and a half ago. And in the truth books, there’s a slim little book by a guy named Lee McIntyre, who’s a philosophy professor, called Post-Truth, I believe. And it’s sort of a wonderful summary on the philosophy and politics of thinking about truth in public life. There’s a lot of books coming out on the subject. That one I liked a lot.

BT: I imagine most people who have the type of relationship with books that you have started young. What were your favorite books as a child?

CL: Oh, gosh. By far — well, I shouldn’t say by far — a book that I still come back to and read at least once a year and now I’ve just read it with my children is Harriet the Spy. I loved Harriet the Spy. Hated the movie. No one should watch that movie. But I loved Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh. I have nothing in common with Harriet. You know, she’s this rich, Upper East Side brat. And yet, I wanted to be her. She always wanted to be a spy and a writer. And when I was a kid, I was blown away by reading her. And then later, I read the sequel, called The Long Secret, which is actually a wonderful summer book because it’s Harriet and one of her friends at the beach.

Also as a kid, I read this series of books called The Great Brain by this guy named J.D. Fitzgerald, who was — it’s basically reminiscing about his childhood growing up as the only Catholic family in this little Mormon town in Utah. And I read those obsessively. I still have the original copies that I read in the early ’80s. And those are the ones that I’m reading now with my own kids. Looking back on them, I think I had nothing in common with these characters except that they felt like outsiders. They felt kind of uncomfortable, sometimes, in their own place, in their own skin. And they were always striving for something more. And they just stayed with me.

And then as a teen, I think I read every Agatha Christie murder mystery that she published. I just went on this tear where I was obsessed with those.

BT: I wouldn’t be a very good alumni magazine interviewer if I didn’t ask you about your Princeton experience and how that may have shaped the work that you do today. So is there anything from your Wilson School experience that you come back to as a reviewer?

CL: As you can imagine, there’s a ton of Wilson School grads in Washington. And so first of all, it was just a great community that I was able to spend two years with. And I still see a lot of those people. We just had a Fourth of July barbecue at the house of someone that I met at Princeton. And all the people who were invited were from that same graduating class at the Wilson School, or, you know, plus or minus one or two years.

You know, when I went there, I really thought that, as I mentioned, that I just wanted the sort of analytic and technical grounding in public policy and economics. And I certainly got some of that. But when I think back on it, it sort of fits with what I’m doing now in the sense that some of the things I remember reading, again, are those things that stay with you. Don Stokes [’51] was this famous political scientist who taught a policy seminar at the Wilson School. And he made us read portions of Robert Caro’s The Power Broker. And that look at the brutal politics of public policy was extraordinary and was so useful to think about as a 22-year-old, 23-year-old kid. I was fairly young at the Wilson School. And also, we read a book called Protecting Soldiers and Mothers by Theda Skocpol, about the origins of the welfare state in the United States. And again, it was that intersection of hard political reality with social policy. And so those readings, and our conversations and discussions about those readings, were really formative for me, in ways that I only realize years later, looking back. So I’m grateful to the Wilson School for that.

Princeton is a place that, as a graduate student, feels very geared to its undergrads. And that’s fine. I mean, that’s what it should be, I think. But I certainly got a lot out of it in ways that only became more apparent over time. My first job at the Post was as economics editor. And certainly the fact that I’d studied public policy at Princeton didn’t hurt me in that capacity. And my year of doing that job was precisely when Bernanke became the Fed chairman. So I felt I had some insight that I could offer to the reporters who were working on that and that I was editing.

BT: Did you pull out your lecture notes from the Wilson School?

CL: I did. I actually took a... what was it called, advanced macroeconomics class with Bernanke. We used his own textbook, too. Abel and Bernanke was the book. But I did, and I wrote, just when he was becoming Fed chair, I wrote a piece for our Sunday opinion section about what it was like to take his class.

I remember this great moment in either a midterm exam or his final exam, where he asked a question that was far beyond anything that we had covered in the class. And some of the students, some of my classmates were upset by this and complained to him in a subsequent class. You know, why did you ask us this thing? We have no basis of being able to answer it because it wasn’t anything he covered. And he just looked at us and said, “I don’t see an exam as simply an opportunity to spit back out what you’ve learned in class. The exam itself is a learning opportunity.” Right? And that always stayed with me. So I wrote about that in this essay and thinking, of course, that now he was going to have his own learning opportunity in switching from the academy to the chairmanship of the Fed.

BT: I remember when he began the chairmanship that I did an interview with Alan Blinder [’67]. And he talked about how Bernanke would be so much easier to understand versus Greenspan. You wouldn’t have to parse his words quite as much. I don’t know if it exactly bore out the way he expected it to.

CL: No, I think that’s probably right. I mean, Greenspan was so famously cryptic. And I’m sure that that experience of teaching undergrads and a bunch of ignorant graduate students like me was probably helpful in spelling out policy. And he’d been — I just remembered — of course, he didn’t come straight from Princeton. He had been chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors for Bush before becoming Fed chairman. So then again, it’s a low bar in trying to be more understandable than Alan Greenspan.

BT: Well Carlos, thank you so much for doing this. I really enjoyed speaking with you.

CL: It was a real pleasure. Thank you.

BT: You can read Carlos Lozada’s reviews at washingtonpost.com and in the Sunday Outlook section of The Washington Post print edition.

If you’ve enjoyed this podcast and would like to hear more, please subscribe to Princeton Alumni Weekly Podcasts in iTunes. And if you’d like to read more about Princeton authors — alumni and faculty — check out our monthly Princeton Books email newsletter. You can sign up at paw.princeton.edu/email.

Paw in print

January 2026

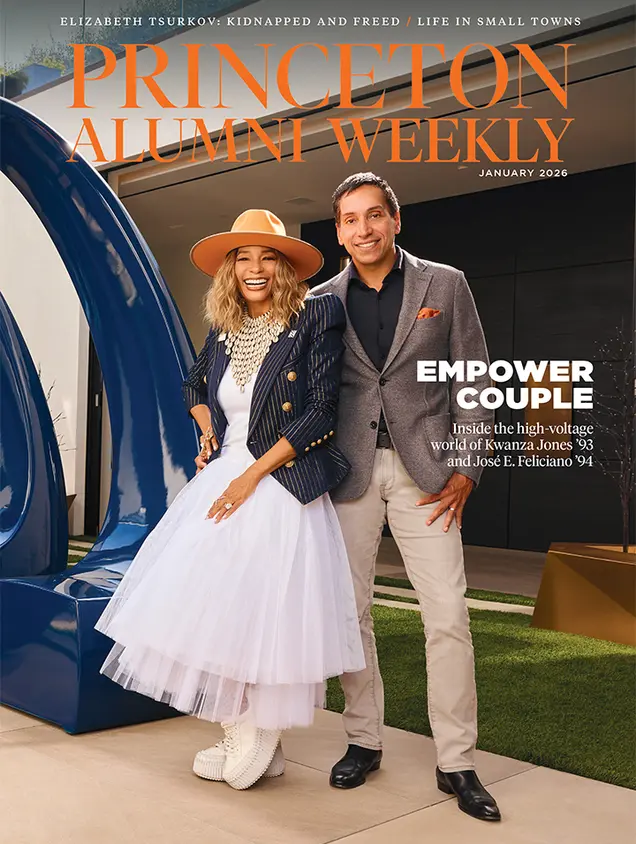

Giving big with Kwanza Jones ’93 and José E. Feliciano ’94; Elizabeth Tsurkov freed; small town wonderers.

No responses yet