PAWcast: Eric Schwartz *85 on Ukrainian and Global Refugees

‘The suffering of anyone, no matter where they’re from, should command the attention of humankind’

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted a flood of refugees seeking safety in Europe, the U.S., and elsewhere. As president of Refugees International, Eric Schwartz *85 has had an eye on the situation, and on refugee crises in places that aren’t receiving as much attention. Schwartz spoke to PAW in mid-March about what he saw in Ukraine during a trip there early in the invasion, and about the policy solutions that are needed not only for Ukrainian refugees, but others around the world. At the time, the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) thought 4 million refugees would flee Ukraine; by this podcast’s publication in late April, that prediction had climbed to 8.3 million, according to NPR.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Google Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

TRANSCRIPT:

Liz Daugherty: At the beginning of March, Eric Schwartz *85 was in Poland watching Ukrainians cross the border to flee the Russian invasion. Schwartz, who earned his master’s degree from the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, is president of Refugees International, an independent advocacy organization started in 1979 that elevates the voices of global refugees and pushes for policy solutions. Schwartz has had a long career in human rights and refugee policy work, including as U.S. assistant secretary of state for population, refugees, and migration during the Obama administration. He spoke with PAW from Maryland, where his organization is advocating for Ukrainian refugees as well as others in crisis situations around the world.

Eric, thank you so much for coming on the PAWcast.

Eric Schwartz *85: It’s my pleasure.

LD: So what are you seeing and hearing from the people fleeing Ukraine?

ES: Well, we were in Poland from March 3 through March 9. And Poland is hosting the majority of the refugees who are coming over from Ukraine. And what we’re hearing is that people, what we heard, was that people were leaving very desperate situations and circumstances. The Russian military and the Russian government are engaged in a concerted campaign of attacking civilian institutions and civilians, surrounding cities, and making life miserable in violation of the laws of war. And as a result, you know, people who we got to talk to, mostly, not mostly but exclusively women from Ukraine, because they represent the overwhelming — they and children represent the overwhelming majority of refugees. And what we heard were terrible stories about people whose children’s schools were destroyed, people who had to take shelter in bathrooms or in basements while attacks took place against civilian institutions, apartment buildings, and the like. And just a very difficult and desperate situation.

We visited four border crossing points, and at each one of those points, people were very determined to get on to other parts of Europe, but they were also very tired, very dispirited, and certainly not wanting to leave their country of origin.

LD: As they’re leaving, are these people planning to be gone forever, or are they thinking that they’re going to be able to come back some day?

ES: Well, it’s hard to know what people are really thinking and feeling, but the individuals with whom we spoke clearly wanted to be back in Ukraine, and I think had some strong expectations that they would be able to return sometime soon. But I also think that, in these circumstances, there’s an awful lot of uncertainty. People just don’t know. Thankfully, the governments of the European Union have — and the European Union itself — has issued a temporary protection directive that will give Ukrainians and some non-Ukrainians as well, who fled Ukraine, the opportunity to live and to work in European Union countries for up to three years, one year at a time. The directive is initially for a year, but it could be up to three years. And that’s very good news.

The large majority of people who are crossing into Poland, you know, had a sense of where they wanted to go. Either to connect with relatives, with friends, and at the time of our trip, about a week or so ago, it seemed as though a significant majority of people had someplace to go. But there were people who were going onward. In fact, we met, I believe it was in the town of Przemysl, we were at a sort of a makeshift, I believe that was the town, one of the border areas that we visited. And we met a fellow from Finland, some folks from Germany, others from the Czech Republic, all of whom were there to transport Ukrainians who wanted to go to those countries, who might want to go to those countries. And there was a lot of that — there is a lot of that happening.

LD: Well, that’s heartening, at least, to hear that maybe there are, you know, they’re getting a welcome.

ES: It’s very heartening. I would just say that, you know, it is very heartening. It’s very encouraging. The general response thus far, although the issue of how long the response will be sustained is an important one. But the response so far has been very encouraging on the refugee side.

There are two issues that I think have to be mentioned. The first is that, you know, the generosity that we’re seeing from European governments and civil society, governments in particular, for the purposes that I’m about to describe, you know, has not always been reflected in other refugee situations. Whether it’s Afghans or third-country nationals from countries in Africa, or Syrians — with the exception, of course, from the response by the government of Germany several years ago, many years ago — we haven’t always seen that level of generosity coming from European governments. And the answer, of course, is not to diminish the level of generosity and support that we’re seeing for Ukrainian refugees. The answer, of course, is to ensure that that level of generosity is matched in other refugee situations. And that European governments promote this principle of humanity, that the suffering of anyone, no matter where they’re from, should command the attention of humankind.

And so that’s one issue that, for those who are concerned about humanitarianism, and welcoming the stranger, as happy, as encouraging as you can — as encouraging as it is to see this response in Europe, there is this sort of nagging feeling that, OK, now we have to do better by refugee populations everywhere. So that’s one issue that I think is very important.

And the second issue that is extremely important is the situation within Ukraine, that, you know, the far more dire humanitarian situation, from my perspective — and not to diminish the suffering of people who have to flee their homes and have to cross borders, I certainly don’t want to diminish the importance of appreciating that degree of suffering. But the more dire humanitarian situation right now is within the borders of Ukraine. At this point, it’s estimated that upwards of two million people are internally displaced within the country. That figure may be low. The U.N.’s appeal estimates that over the course of three months that number could be as high as 6.7 million. The Russian tactics of bombardment, of laying siege to cities and bombarding civilian institutions — schools, hospitals — that is creating enormous suffering, and the challenge — putting aside the challenge of getting the Russians to stop this terrible offensive and to comply with the rules of warfare, and there are rules in warfare. You don’t wantonly attack civilians. Putting those issues aside just for a second, you know, the challenge for the humanitarian assistance community will be to provide critical assistance to these millions of Ukrainians who are already in dire need, and right now, the United Nations, private agencies, international voluntary organizations, they’re all sort of gearing up for this challenge, but it is going to be significant and substantial.

LD: I think those are two really important points. I want to come back to your first one about other refugee crises, because I think that that’s a really important piece of this. But really quickly, just to jump on the second point you made about this humanitarian situation happening within Ukraine, when you talk about people who are internally displaced, can you give me a sense of what that looks like? Because I think it’s really important to sort of understand what is it? Are we talking about people who, like, their home is bombed and so they’re staying with friends, they’re staying — where are they? Are they staying in shelters, schools, you know, what — how are they getting food? Can you tell me anything about what that looks like, from what you know?

ES: Well, typically, you know, there are circumstances and situations where people who are internally displaced are in camps, are in encampments. But typically that’s not the way it happens in a majority of cases, and people who are — you know, if you’re displaced, it means you’re outside your home. You can be staying in temporary facilities, you can be staying with friends. You can be on the run. There are just a variety of circumstances that internally displaced people can find themselves in, especially in a situation of significant conflict and one that is sort of rapidly evolving. I can’t tell you where the upwards of two million Ukrainians who are internally displaced right now are situated. There may be some in encampments, especially in areas like western Ukraine, in and around Lviv. But I don’t really have that information. I’m not saying it’s not available. I just don’t know it.

LD: Yeah, no problem. Let’s go back to your point, then, about other refugee situations. Your organization, Refugees International, is working in a bunch of different places around the globe. These places are not getting the news media attention that Ukraine is. I don’t think they were getting it even before the Ukraine conflict started. So can you tell us, where else is there a crisis that you guys are looking at?

ES: Well, I think, maybe in some respects the most significant displacement crisis that we’ve seen in recent years has been the displacement crisis involving Syrians, where, you know, don’t quote me on these numbers, but were upwards of five, six, seven million Syrians have been internally displaced, displaced within the borders of their own country, and about an equivalent number have been — are refugees outside their countries of origin. And in places like Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and living in circumstances where the likelihood that many, if not most of these Syrians who are outside the borders of their country, will return — that likelihood is very uncertain.

None of those governments, none of the governments that are hosting them, have moved forward on serious plans to integrate these refugees into the host populations. There have been some efforts to provide opportunities to work, to provide some opportunities for status in a place like Jordan. But the relationship between the refugee communities and their hosts, at best, is uneasy, and at worst can be very hostile.

And so, you know, we have taken the position — I have taken the position that one of the ways to encourage host countries like Jordan, like Lebanon, like Turkey, to be more generous to refugee populations is to — for the United States and other high—income countries to demonstrate a commitment to responsibility sharing that goes beyond simply the provision of money, but also is manifested in a commitment to some degree of resettlement of these refugee communities. It is clear that resettling in the United States will not be the solution for the majority of Syrian refugees in the world. But we have resettled a minuscule number of Syrians, and I think if the United States made a commitment — I urged several years ago that the U.S. make a commitment to resettle about 100,000 Syrian refugees. That is a drop in the bucket in terms of what the overall need for durable solutions for Syrian refugees may be, but at least it would signal a willingness on the part of the United States to engage in serious responsibility sharing. That, indeed, is what the government of Germany did about six, seven, eight years ago, and I think it sent a very important signal to the world.

To my mind, the Syrian refugee situation is perhaps the most significant one in terms of the degree of human suffering and the degree of need reflected simply in the numbers and the circumstances and conditions involving that population.

LD: Well, that starts to answer what was going to be my follow-up question: What needs to happen from a policy perspective for our country, for countries in Europe? I think you’ve already answered that in part, but is there anything else there that your organization is advocating for that it feels strongly needs to happen?

ES: Yeah. I mean, look, I think there’s, on several different levels, action needs to take place. First, don’t get me wrong. I think governments that are hosting refugees need to do better by them. Whether that’s Bangladesh that is hosting upwards of a million Rohingya refugees from Burma, whether that’s the government of Jordan that’s hosting Syrian refugees, whether that’s the governments in South America that are hosting Venezuelans who have had to flee the regime in Caracas. All of those governments, even if they’re not in a position to provide, say, citizenship for refugees, which would be sort of, you know, which would reflect an intention to fully integrate refugee populations, they can at least recognize that for many of these refugee populations, the prospects of returning to their country of origin are slim in the best of cases, and therefore, these refugee populations in host communities need opportunities to work, to have their status regularized, to have their rights respected.

So that’s an important responsibility for host governments, and I think high-income governments and international organizations like the World Bank can provide significant financial assistance both to host communities and to the refugee communities so as to ease that process of acceptance. And that’s an important responsibility that the United States and other high-income governments should undertake.

But I also think that governments like the United States also have to do their fair share with respect to refugee resettlement. And our record with respect to refugee resettlement — the experience of resettled refugees in the United States has been a very positive one. They have strengthened our communities. They have revitalized cities, you know, with an aging population, as we have, they, you know, refugees, you know, make important economic contributions and play an important role in the future of our own country. So I think that kind of commitment, which was very much diminished in the former administration and needs to be reestablished, is a very important one.

LD: I don’t know if you’re in as good a position to answer this question, but I figured I would ask because a lot of people I am seeing feel very sympathetic and empathetic with what’s happening in Ukraine. Maybe that’ll bring attention to some of these other refugee crises. And from an individual perspective, if they want to do something to help, do you have any suggestions for what people can do over here? I’m seeing a lot of wishing that they can help, a lot of donating clothes, kind of the usual things. Do you have any suggestions for what people can do?

ES: Yeah, I mean, I would say in general, donating, clothing and, you know, food and other kinds of items like that really, that would not be the way to go. It’s not a very efficient way to provide support. I think the most tangible way, you know, a citizen, you know, anyone can provide support, is to identify organizations that are doing good work and contribute to those organizations. You can also — there are also volunteer opportunities with organizations, especially refugee resettlement organizations. There are eight or nine national resettlement organizations. There may be volunteer opportunities within organizations like HIAS, the International Rescue Committee, the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service. These are resettlement organizations. And so there may be opportunities to volunteer.

But if you’re looking for opportunities to help financially, I would provide assistance, provide support, for organizations that are doing important work in the case of Ukraine, organizations like Caritas, like HIAS, like the International Rescue Committee, providing services. And then organizations, if I may be so bold as to say, organizations like ours who are involved in — like Refugees International — that are involved in reporting and advocacy. Because our view is the provision of services is critical, but the perspectives and policies of governments and international organizations are absolutely critical because they shape how the response is moving forward. And so what we do is we do reporting, policy advocacy, and what other organizations do is the provision of services.

LD: Well, what do you think is going to happen in Ukraine going forward?

ES: Well, and now I’m going, admittedly, a little bit beyond my humanitarian brief, but I will say, you know, that this war is going to end one way or another. And I think that, you know, I think that the — assuming that President Putin is not deposed, then he will need some sort of off ramp that also meets the vital concerns of the government of Ukraine. And I think that is really what diplomats, you know, need to be negotiating.

But in the meantime, I think the more we shine a light on the terrible abuses of human rights, of humanitarian law, that are being perpetrated by the Russian military and the Russian government, I think the more important that is, because it brings pressure to bear against the Russian government and the Russian military, and I think, frankly, whether or not they are ever held accountable — and I think they should be held accountable — but whether or not they’re ever held accountable, I think that pressure from organizations like ours, from human rights organizations, is very important, because I think it increases the likelihood that there will be some sort of negotiated outcome that meets the fundamental concerns of the government and the people of Ukraine.

LD: Well, thank you for the work that you’re doing, and thank you for coming and speaking with me today. This is really interesting, and frightening, and it’s nice to hear everything that you’re doing and your suggestions as well for what others can do. So thank you for your time. I really appreciate it.

ES: It’s my pleasure. I enjoyed it.

PAWcast is a monthly interview podcast produced by the Princeton Alumni Weekly. If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and Soundcloud. You can read transcripts of every episode on our website, paw.princeton.edu. Music for this podcast is licensed from Universal Production Music.

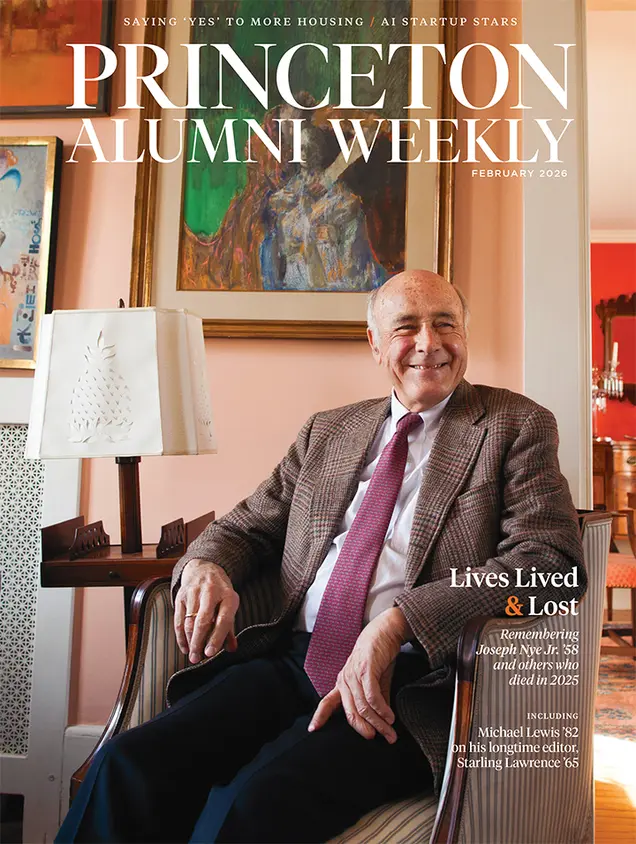

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet