PAWcast: Former Rep. Jim Marshall ’72 on Life as a Student Veteran

Four years at Princeton, interrupted by 21 months in the Army

Two years after leaving Princeton to serve in the Army in Vietnam, Jim Marshall ’72 returned to a campus roiled in conflict. He says that he felt like “an oddity” of sorts — an undergraduate who had seen the war firsthand. Marshall would go on to law school, a career in politics that included four terms in the U.S. House of Representatives, a visiting teaching appointment at Princeton, and a stint as president of the United States Institute of Peace. He’s played a leading role in the recent formation of the Princeton Veterans Association, and he advocates for more opportunities for student veterans. “It’s good for Princeton to be open and supportive, and as helpful as possible, to veterans who have served,” Marshall says.

Listen on Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Soundcloud

This is part of a monthly series of interviews with alumni, faculty, and students.

TRANSCRIPT

Brett Tomlinson: I’m Brett Tomlinson from the Princeton Alumni Weekly, and I’m here with Jim Marshall ’72. Jim has had a remarkable career post-Princeton as a lawyer and legislator. He served four terms in the United States House of Representatives as a Congressman from Georgia. He is also a former president of the United States Institute of Peace. At Princeton, he had a unique undergraduate experience that included a two-year absence for military service, and Jim is also one of the leaders of the new veterans association at Princeton, P-VETS. So we have lots to discuss, and Jim, I thought it would make sense to kind of start at the beginning. Can you tell me a bit about where you grew up, and how you found your way to Princeton initially?

Jim Marshall: So, I was the son of a West Point grad, and the grandson of a West Point grad, and so I was headed to West Point, as, you know, a military brat. And my dad wanted me to promise him that I would make a career of the military. I was 17 years old. I look at my father and say, “Dad, I don’t even know what I’m doing Saturday night, how can I promise you what I’m going to do for the rest of my life, basically? I can’t do that.” So, he said, “OK, I don’t want you going to West Point, maybe taking a slot from somebody who is committed to a career.”

Well, what else was I going to do? You know, being very presumptuous concerning my abilities, and etc., I was actually interviewed by the school newspaper down in Mobile, where was I going to go to school? Well I was no longer going to West Point, so I just said, “Princeton or Harvard.” What in the world would make me think that that could happen? But I did go to Princeton. And so, that’s pretty much what did it, it happens that we have relatives that were near to Princeton. I had other offers, my father really liked the honor code. I liked the honor code as well. It was very similar to West Point’s honor code. You know, no cheating, no lying, etc., and you won’t tolerate other people who do it. And so, one thing led to another, because of the proximity, because of the honor code, because I wasn’t going to West Point, I went to Princeton.

BT: And how did Princeton then compare to the schools that you had grown up going to, and how did you adjust to whatever it was that was kind of new and different about Princeton?

JM: Well, I was very fortunate to be born in the family I was born in, my parents were both well educated, very smart, they were insistent that we learned good values, that we got good educations, that we were good people. The schooling was all Catholic, except for one year. And I was — it was good schooling, no question about that. And came to Princeton, I think, pretty well prepared for Princeton academically, not necessarily for Princeton’s social atmosphere. I was the oldest of eight in a military family, the deal was, you know, I got a National Merit scholarship, and a Princeton scholarship, and you know, had federal loans, student loans. But I had to work a whole lot of jobs because the deal was, don’t take any more money than necessary from the family, and if you take money from the family, pay it back as quickly as you can, because there’s seven younger brothers and sisters that need to go to college as well. So when I came to Princeton, it was on a bus from Mobile, Alabama. I’d never been here before. I was tossed into Edwards with three other guys I’d never met before, my roommates. And I worked the laundry, at the student center, the cafeteria, sold souvenirs at the football games. I mean, just stuff like that, to try and make ends meet. I was really impressed by how smart just about all of the people, and certainly my roommates, and people in Edwards and whatnot, were. They were a lot more diligent than I was. I wasn’t really good about going to class, and you know, doing things in an orderly way, as opposed to just waiting to the last minute to do them. I mean, I would routinely not go to class.

I mean there were classes that — Professor Leibler gave me a very bad grade in linear algebra, I deserved it, I thought I could just blow it off, and read it the day before, and come in and take the math test, I could always do that in the past, and I couldn’t do this one. And I wound up calling him up, this is before I left, I wound up calling him up, and he said, “Oh you’re the one from Alabama.” I said, “Well how would you know that?” He said, “Well I always like to know something about a student before I give them a grade, and since you and Braswell didn’t come to class, I asked for your transcripts. You know, you have quite an aptitude for mathematics.” I then started whining about, you know, I have this personal issue, and I couldn’t do the — he cuts me off. “You’re too late, I’ve turned in the grades.” I can’t say anything at that point. He pauses, “Would you like to know how you did?” “Yes, sir.” “You failed. But, I never give anybody a failing grade in linear algebra, you might want to tell Braswell that, too.”

And so it was that kind of behavior that was really not appropriate, and maybe I just, you know, I was in the straits of an Army family, Catholic — and then all of the sudden I’m sort of free to do what I want to do. And so that was sort of my first two years at Princeton.

BT: And after that second year at Princeton, I guess heading into your junior year, you made a choice that I gather was atypical?

JM: Atypical. It was entirely unique.

BT: You decided to enlist.

JM: How’d that happen? OK. So, you know, I came from a military background, I wasn’t that far, you know, from understanding what this would involve and, you know, feeling committed to, you know, my country first, I should serve, that sort of thing. I really thought it was crappy that I had a student deferment, I and fellow Princetonians had student deferments. So we were exempt from the draft. And all these kids, you know, mostly poor, often of color, who couldn’t get into college, or couldn’t figure out how to get into the National Guard, or the Reserves, or something like that, were getting drafted and sent over to Vietnam as cannon fodder, and it really, the whole debate about that, heightened dramatically 50 years ago, when the Tet Offensive occurred. And so, I was arguing that it was better for us to drop out, and go serve.

I’d been screwing around as a student, I really wasn’t applying myself like I should have. I wound up getting married at this, the end of my sophomore year, to my high school sweetheart, whom I loved dearly, but the marriage was not a good idea. We were both too selfish, too young. And so, I had decided I was going to do economics, and had an economics paper due. And I didn’t want to do it. The marriage wasn’t going well, I’d already said I should enlist, so instead of doing the paper, I got on a bus, went up to New York, and enlisted.

BT: And what was the reaction when you made that choice? How did your family, how did your father feel about your decision?

JM: You know, I didn’t ask before I did what I did. I didn’t ask anybody, I just went and did it. And you know, what could my father say? You know, he was going to be supportive, obviously.

My mother was totally distraught. She used to write me letters all the time, she could not write me a letter after that. She was really worried about this. At one point — eight kids — one of her friends said, “But you’ve got eight kids,” and her response was, “I didn’t know I had one to lose.” So, it, you know, lots of people weren’t real happy about it. I was fine. And then, you know, you go and you take their tests, obviously I did well on the tests, do I want to go to OCS? No, that’s three years minimum. I’m going to do two years and get on with my life. I’m not going to make a career out of the military. “Do you want to work with computer systems that control guided missiles?” No, that’s not what I — “What do you want to do?” And this was a lieutenant who said this to me. And I remember verbatim, what I said in response, because I remember what he said. I said, “I want to be in the infantry, jump out of airplanes, and go to Vietnam.” He leaned forward, looked at me, and said, “We’ve got plenty of openings, you’ll have no trouble.”

And so, and then I found out about NCO school, so I was a sergeant. Found out about Ranger school. So I did all that kind of stuff, and went to Vietnam, and it was a — I mean, bad things happened. I got wounded three times. That was OK, that wasn’t a bad thing that happened. And it was easily the best thing I could have done during that period of time. Made plenty of mistakes, but I should have been paying the military, the military should not have been paying me. I learned so much, I matured so much, I got to do things that were just stunning.

And came back to Princeton. I was big enough to play lightweight football. I remember doing jumping jacks, the co-captains, we were going to go play Navy, and they were going — their cadence was, “Kill Navy, kill Navy,” and I was in the back, thinking, “Well they are Navy pukes, but last time I checked, they’re on our side, so I’m not going to say, ‘Kill Navy.’” And of course, we went and played them, and they killed us.

BT: You said that it was going to be two years, and that’s it. Did you have any doubts, any reservations about whether or not you would come back to Princeton? Was that kind of a foregone conclusion, or did you think that maybe your future lay somewhere else?

JM: Well actually, I checked on that. I left in good standing. And they said, please come back. They — I don’t know exactly who. But, and if you come back, you’ll get your scholarship back, and your room back, and all that kind of stuff. So, that’s what I intended to do all along.

I had left in October. Coming back in October would have been a problem. You know, two years. But I found out that you could get an early out, 90 days, to go back to school. I was knocked out of combat by wounds, and then I was teaching in the rear, and I found out about that. And I applied, and they — so my entire tenure in the military — I guess I was released maybe a week or two before Princeton was scheduled to start in 1970. And my total time in the military was 21 months and 1 day.

BT: And you came back to a campus that had —

JM: Oh, roiled with conflict.

BT: In the spring of that year, the students had gone on strike. You come back in the fall, what was it like to be a young veteran entering your junior year at Princeton?

JM: Well, as you might imagine, I was kind of an oddity. And, you know, people were real curious. I remember giving a talk about my views of Vietnam, a lot of people there, you know, how I thought we ought to be going about this, which was not the way that we were going about this, I don’t know whether I was being naïve at the time, just don’t know. But, no, I just came back, going to finish, you know, get my degree, you know, played football one year. You know, never — it was sort of the same thing. I mean I worked a lot of jobs, had the GI Bill. I didn’t even know about the GI Bill when I enlisted. And so, I came out, and not only did the GI Bill help me get through Princeton, but it also paid for two years of law school later. So, I didn’t go directly to law school. I did a bunch of other stuff. But the GI Bill was very helpful, I didn’t even know about that.

BT: You mentioned that the experience of serving in the Army was maturing for you. How were you different as a student when you came back to Princeton?

JM: Huge difference. I’d actually read the stuff and go to class. Prepare for exams, take the exams. I mean I was normal. Had a hard time, you know, getting motivated to do my senior thesis, but it was great.

BT: In hindsight, it sounds like the route you took probably served you better than if you had gone to West Point.

JM: I think there’s no way to know. You know, you jump into the West Point culture, you do not have the option of not going to class. You do not have the option of not studying before you go to class. And so I think I would have behaved differently, because I had to behave differently. But at Princeton, you can do what you want to do.

BT: I wanted to speak with you about the Princeton Veterans Association; I know Reunions this year has been something of a kickoff, or a celebration of getting this organization off the ground, and getting more alumni involved. Why did you think it was important, and how is it going so far?

JM: So I’m involved in Alumni and Friends of Princeton ROTC. I’m a friend, I’m not an alum. And I’m the president of that organization right now. What that group does is we develop resources, and then lend whatever advice and you know, personal one on one, what have you, kind of stuff, we can, to help with the ROTC program, and in particular, with cadets. We’ve been doing that for a while. West Point, I had — I chaired the board of visitors at West Point, at one point. I really thought that was pretty cool, since my father and grandfather both went to West Point. My father told me not to go to West Point, and here I am chairing the board of visitors, which is kind of like a board of trustees. But anyway, at West Point, John Melkin, at West Point, came up with the idea of teaming up with, he’s got a degree from Princeton he, you know, Princeton, Harvard, Yale, to do annual conferences, seminars, whatever you want, colloquiums on civil-mil relations. And rotate it through those four schools.

It turned out that Harvard and Yale actually had associations, veterans associations, that are similar to the association that we just founded, today, at Princeton, with the blessing of Princeton, in a big way. And Princeton didn’t have anything like that, and there wasn’t really the entity that was needed at Princeton in order to participate appropriately in this relationship that had been prompted by West Point. So, Drew Davis [’70], Ray Dubois [’72], Kirk Unruh [’70], and a number of other people, but they were principal drivers of this. Drew Davis actually put together, Andrew Davis, Class of ’70, he put together an actual proposal on how we could do this. Which, we should organize ourselves here at Princeton. We got with the administration, and it took a, just like a three- or four-year, at least, effort here, because the university here, Princeton, has been organized, its alumni are organized mostly around classes. And it’s worked well for Princeton. And so, Princeton didn’t want to jump into some other way of organizing its alums that might detract from what seems to be working. And so it took a while, and now we have the Princeton Veterans Alumni Association, which we call P-VETS. There’s a Princeton staffer, Emily Latham, who is specifically assigned to this effort. And what I hope, what I expect, is that we’ll pull in, and hopefully get interested in Princeton, veterans who, you know, in recent years have not been interested in Princeton, for one reason or another. And in some instances, because they’re really irritated about the whole Vietnam stuff, and the protests, and kicking ROTC out, and stuff like that. We’ll pull them in, and we’ll have this network of individuals that’s able to recruit veterans to become Princeton students, counsel Princeton students who are veterans, maybe support and help with the ROTC program, and work on these colloquiums — the Woodrow Wilson School did one called Defending Democracy; we were actively involved in making that happen, and helping structure what it was, and that happened earlier April, I guess, this year, and it was great. It was fabulous. And so, I’m real pleased. Drew Davis is going to be the first president. In the businesses that I have been involved in, political mostly, or as a lawyer, it is wonderful when somebody comes in and gives you a package, instead of comes up with an idea and then you’re expected to come up with the actual structure. And Drew came in with the package. And he’ll be a great leader.

BT: There is an effort on campus to recruit more veterans to the undergraduate college. There are veterans in the graduate ranks, there is an ROTC program, Army ROTC, Navy recently returned. What do you think is the benefit to Princeton of having veterans on campus?

JM: When I came back from Vietnam, I was an anomaly. And an awful lot of people wanted to talk to me about well what’s the military like, you know, what was your life like, you know? What do you think about this, what do you think about that? And so, I’m able to — I was then able to bring a vantage point that was informed by actual experience, that would enrich their understanding of how all this works, and doesn’t work. Because a lot of it doesn’t work, and why doesn’t it work? What we should and should not be doing, how all these problems unfold. That’s one thing.

The second thing is that it’s good for Princeton to, and other institutions are doing this quite well, it’s good for Princeton to be open and supportive, and as helpful as possible, to veterans who have served, served well, hopefully, and it’s a contribution that Princeton can make, you know, think about our motto, “Service to the nation and humanity.” That’s very similar to the attitude that — well, very similar, it’s essentially the attitude that good military personnel have toward enlisting, and then doing what they do in the military, whatever it is. There’s a very small number of people, percentage-wise, it’s extraordinarily small, that wind up getting into the kind of combat that I was in, I was just really intent on doing just that. You know, be at the tip of the spear. But everybody who serves learns things about us, and about how we work, and has this opportunity to serve in ways that Princeton, frankly, should honor.

BT: Well Jim, thank you so much for joining me, this has been a pleasure.

JM: Brett, appreciate it.

BT: Alumni veterans who are interested in joining P-VETS can sign up by updating their veteran status in the alumni directory on TigerNet. Additional information is available at pvets.org.

This interview was recorded at the Princeton Broadcast Center with help from Dan Quiyu. The music is licensed from FirstCom Music.

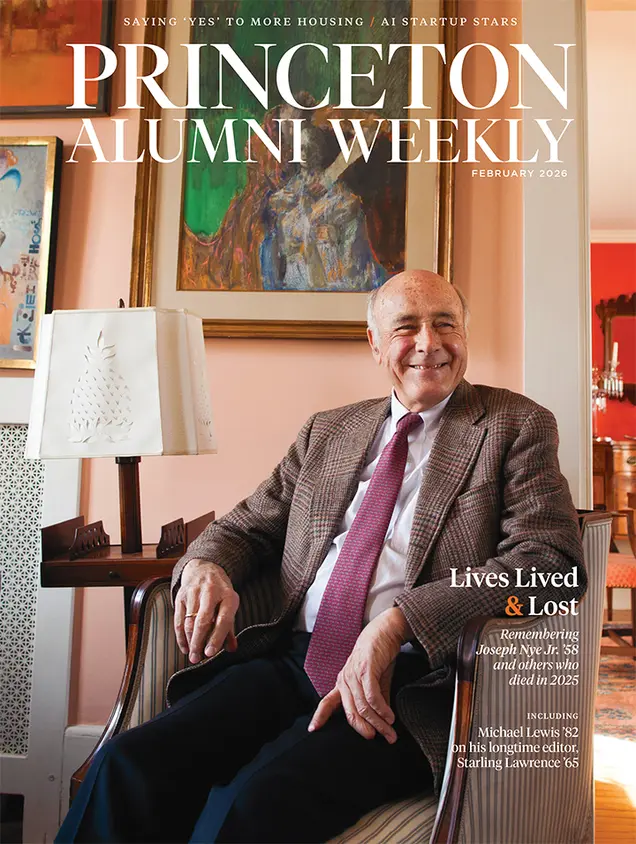

Paw in print

February 2026

Lives Lived & Lost in 2025, Saying ’yes’ to more housing; AI startup stars

No responses yet